Local for Locals Or Go Global: Negotiating How to Represent UAE Identity in Television and Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Land Plots for Sale

Land plots for sale Dubai Holding Creating impact for generations to come Dubai Holding is a global conglomerate that plays a pivotal role in developing Dubai’s fast-paced and increasingly diversified economy. Managing a USD 22 billion portfolio of assets with operations in 12 countries and employing over 20,000 people, the company continues to shape a progressive future for Dubai by growing $22 Billion 12 121 the city’s business, tourism, hospitality, real estate, media, ICT, Worth of assets Industry sectors Nationalities education, design, trade and retail. With businesses that span key sectors of the economy, Dubai Holding’s prestigious portfolio of companies includes TECOM Group, Jumeirah Group, Dubai Properties, Dubai Asset Management, Dubai Retail and Arab Media Group. 12 20,000 $4.6 Billion For the Good of Tomorrow Countries Employees Total revenue 1 Dubai Industrial Park 13 The Villa Imagining the city of tomorrow 2 Jumeirah Beach Residences(JBR) 14 Liwan 1 3 Dubai Production City 15 Liwan 2 4 Dubai Studio City 16 Dubailand Residences Complex Dubai Holding is responsible for some of Dubai’s most iconic 5 Arjan 17 Dubai Design District (d3) destinations, districts and master developments that attract a network 6 Dubai Science Park 18 Emirates Towers District of global and local investors alike. With our extensive land bank we 7 Jumeirah Central 19 Jaddaf Waterfront have created an ambitious portfolio of property and investment 8 Madinat Jumeirah 20 Dubai Creek Harbour opportunities spanning the emirate across diverse sectors. 9 Marsa Al Arab 21 Dubai International Academic City 10 Majan 22 Sufouh Gardens 11 Business Bay 23 Barsha Heights 12 Dubailand Oasis 9 2 8 22 7 18 23 11 17 19 3 5 6 20 4 1 10 14 1 Dubai Industrial Park 15 13 16 12 21 Dubailand Oasis This beautifully planned mixed-use master community is located in the heart of Dubailand, with easy access to main highways of Freehold 1M SQM Emirates Road, Al Ain Road (E66) and Mohammed bin Zayed Road. -

Architecture and Urbanism in the Middle East

Viewpoints Special Edition Architecture and Urbanism in the Middle East The Middle East Institute Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints is another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US relations with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org Cover photos, clockwise from the top left hand corner: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Imre Solt; © GFDL); Tripoli, Libya (Patrick André Perron © GFDL); Burj al Arab Hotel in Dubai, United Arab Emirates; Al Faisaliyah Tower in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; Doha, Qatar skyline (Abdulrahman photo); Selimiye Mosque, Edirne, Turkey (Murdjo photo); Registan, Samarkand, Uzbekistan (Steve Evans photo). -

PRESS RELEASE for IMMEDIATE RELEASE JUNE 6, 2016 Contact: Shafer Busch, America Abroad Media [email protected] 202-2

View this email in your browser PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE JUNE 6, 2016 Contact: Shafer Busch, America Abroad Media [email protected] 202-249-7380 From Left: Paul Baker, Maryam Almheiri, Aaron Lobel, H.E. Noura Al Kaabi, Ben Silverman, Greg Daniels, and Howard Owens. America Abroad Media Brings Top Hollywood Writer and Producers to Abu Dhabi Last week America Abroad Media (AAM) helped organize a delegation of leading Hollywood producers and writers who traveled to Abu Dhabi for a groundbreaking series of workshops and events aimed at supporting young creative talent in the UAE and the broader Arab World. The delegation included AAM Founder and President Aaron Lobel; Ben Silverman, the Emmy, Golden Globe, and Peabody Award-winning executive producer of The Office, Ugly Betty, The Tudors, Jane the Virgin, and Marco Polo; Greg Daniels, a leading comedy writer, producer, and director on shows such as Saturday Night Live and The Simpsons and co-creator of The Office, King of the Hill, and Parks and Recreation; and Howard Owens, Founder and co-CEO of Propagate Content and former CEO of National Geographic Channels. “Our partners in the Middle East have the ambition and the talent to bring about a new golden age in Arab drama and entertainment," said Lobel, "and they feel that the experience of Hollywood professionals can benefit their efforts. We look forward to forging long term partnerships for Arabic drama and entertainment programming that will reach audiences across the Middle East and far beyond." During their visit, Ben Silverman and Howard Owens shared their experiences in Hollywood with over 100 Arab counterparts and explored how the UAE can become a regional and global center for storytelling, while Greg Daniels hosted two invitation- only screenwriting workshops with writers from around the region. -

Workbench 16 Pgs.PGS

Workbench January 2008 Issue 246 HappyHappy NewNew YearYear AMIGANSAMIGANS 2008 January 2008 Workbench 1 Editorial Happy New Year Folks! Welcome to the first PDF issue of Workbench for 2008. Editor I hope you’ve all had a great Christmas and survived the heat and assorted Barry Woodfield Phone: 9917 2967 weird weather we’ve been having. Mobile : 0448 915 283 I see that YAM is still going strong, having just released Ver. 2.5. Well [email protected] ibutions done, Team. We have a short article on the 25th Anniversary of the C=64 on Contributions can be soft copy (on floppy½ disk) or page four which may prove interesting to hard copy. It will be returned some of you and a few bits of assorted if requested and accompanied with a self- Amiga news on page ten. addressed envelope. Enjoy! The editor of the Amiga Users Group Inc. newsletter Until next month. Ciao for now, Workbench retains the right to edit contributions for Barry R. Woodfield. clarity and length. Send contributions to: Amiga Users Group P.O. Box 2097 Seaford Victoria 3198 OR [email protected] Advertising Advertising space is free for members to sell private items or services. For information on commercial rates, contact: Tony Mulvihill 0415 161 2721 [email protected] Deadlines Last Months Meeting Workbench is published each month. The deadline for each December 9th 2007 issue is the 1st Tuesday of A very good pre-Christmas Gather to the month of publication. Reprints round off the year. All articles in Workbench are Copyright 2007 the Amiga Users Group Inc. -

English Newspapers in the United Arab Emirates: Navigating the Crowded Market

English newspapers in the United Arab Emirates: Navigating the crowded market By Peyman Pejman January, 2009. Dubai’s rapid growth has made the United Arab Emirates a global household name in the space of a few short years. A recent New York Times story referring to the country’s star emirate, perhaps put it best: "You name it, Dubai has it. Or if it doesn’t have it, it’s building it. Or if it’s not building it, it's dredging up an island to put it on.”1 Dubai’s growth has helped turn the United Arab Emirates, a country not yet forty years old, into a symbol of economic development for the rest of the region. But as the country debates its place in the global financial and political arena, there is another field in which the UAE will be tested, sooner rather than later: media development. As the country finds itself more tied to the global economy, English daily newspapers are realizing that the old system of uncritically reporting news in deference to political and business elites is no longer adequate if the papers want to be considered a player in the media market. They are realizing that timid reporting can no longer be washed off with a sea of advertising revenue and that good reporting is becoming more and more essential for earning respectability. This paper is based on first-hand interviews conducted with editors of all six daily English newspapers in the United Arab Emirates.2 As such, it is the most comprehensive research carried out on the topic to date. -

8-2-21 Javed, Faraz Resume

Faraz Javed Represented by The NWT Group [email protected] 817-987-3600 https://NWTgroup.com/client/farazjaved EXPERIENCE 12+ years of digital and broadcast WXYZ, Detroit, MI Reporter experience as a TV producer, anchor, 2021 — Present and reporter / multimedia journalist. Created and developed hundreds of Dubai One (Dubai Media Incorporated), Dubai, UAE 2010 — 2021 news stories related to local politics, • The largest English-language broadcast network in the UAE community-related issues, and economic 2014 — 2021 Senior Producer, Anchor and Reporter development. Produced hundreds of Core Responsibilities hours of programming reaching diverse • Producer for Emirates News - 2x weekly audiences worldwide. Takes ownership of • Exercised final editorial control over what is broadcast on this nightly 30m newscast launching new television channels, • Assigned story coverage to a 10-person broadcast and digital-news team building, and synergizing production • Oversaw all on-air graphics and edits teams as well as leading large crews of • Managed a 10-person editorial and production team newsroom staff. Puts forward a broad • Monitored wires and other news sources for breaking news and story developments and dynamic experience producing a • Reviewed all scripts and provided final approval prior to broadcasting myriad of genres, including News, • Provided information to talent while directing control room staff and on-air products Entertainment, Lifestyle, Sports, and • Directed digital news team on content strategy for online platforms Travel -

George Saltsman Curriculum Vitae

George Saltsman Curriculum Vitae Postal: 9900 Brookwood Ln. College Station, TX 77845 Phone: (325) 829-5872 Web: www.georgesaltsman.com Email: [email protected] Education Ed.D. Educational Leadership. Lamar University (2014) Awarded: Outstanding doctoral student Dissertation: Global Leadership Competencies in Education: A Delphi Study of UNESCO Delegates and Administrators (Conducted in English, French, and Spanish) M.S. Organizational & Human Resource Development. Abilene Christian University (1995) B.S. Computer Science. Abilene Christian University (1990) Professional Employment Director, Center for Educational Innovation and Digital Learning Lamar University: Office of the President 9/2016 - Present Continuation of all previous duties as Director, Educational Innovation. New duties include the establishment and administration of the Center for Educational Innovation and Digital Learning. Currently establishing a $50M USD program, at the request of the Prime Minister of Vietnam, to provide computer science bootcamp training to 200,000 individuals in eight locations. Content and curriculum are sourced and currently in pilot stage. Current activity now involves extending curriculum into secondary and post- secondary institutions. Expected additional funding from Government of Vietnam, Microsoft, Amazon, IBM, and the Prince Andrew Charitable Trust. Currently establishing an Education Design Center, located in Austin Texas, to assist PK-12 school leaders in selecting appropriate pedagogy, training, technology, and educational support -

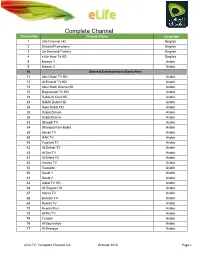

Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1

Complete Channel Channel No. List Channel Name Language 1 Info Channel HD English 2 Etisalat Promotions English 3 On Demand Trailers English 4 eLife How-To HD English 8 Mosaic 1 Arabic 9 Mosaic 2 Arabic 10 General Entertainment Starts Here 11 Abu Dhabi TV HD Arabic 12 Al Emarat TV HD Arabic 13 Abu Dhabi Drama HD Arabic 15 Baynounah TV HD Arabic 22 Dubai Al Oula HD Arabic 23 SAMA Dubai HD Arabic 24 Noor Dubai HD Arabic 25 Dubai Zaman Arabic 26 Dubai Drama Arabic 33 Sharjah TV Arabic 34 Sharqiya from Kalba Arabic 38 Ajman TV Arabic 39 RAK TV Arabic 40 Fujairah TV Arabic 42 Al Dafrah TV Arabic 43 Al Dar TV Arabic 51 Al Waha TV Arabic 52 Hawas TV Arabic 53 Tawazon Arabic 60 Saudi 1 Arabic 61 Saudi 2 Arabic 63 Qatar TV HD Arabic 64 Al Rayyan HD Arabic 67 Oman TV Arabic 68 Bahrain TV Arabic 69 Kuwait TV Arabic 70 Kuwait Plus Arabic 73 Al Rai TV Arabic 74 Funoon Arabic 76 Al Soumariya Arabic 77 Al Sharqiya Arabic eLife TV : Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1 Complete Channel 79 LBC Sat List Arabic 80 OTV Arabic 81 LDC Arabic 82 Future TV Arabic 83 Tele Liban Arabic 84 MTV Lebanon Arabic 85 NBN Arabic 86 Al Jadeed Arabic 89 Jordan TV Arabic 91 Palestine Arabic 92 Syria TV Arabic 94 Al Masriya Arabic 95 Al Kahera Wal Nass Arabic 96 Al Kahera Wal Nass +2 Arabic 97 ON TV Arabic 98 ON TV Live Arabic 101 CBC Arabic 102 CBC Extra Arabic 103 CBC Drama Arabic 104 Al Hayat Arabic 105 Al Hayat 2 Arabic 106 Al Hayat Musalsalat Arabic 108 Al Nahar TV Arabic 109 Al Nahar TV +2 Arabic 110 Al Nahar Drama Arabic 112 Sada Al Balad Arabic 113 Sada Al Balad -

Transformative Banking - Go Digital with Disruptive Technologies

Transformative Banking - Go digital with disruptive technologies issue 16 inside this issue From the Managing Director’s Desk From the Managing Director’s 1 Dear Readers, Desk As we settle down in the digital era, there is a lot to look at Banking 2020: Technology 2 and contemplate. Business, as we know it has changed. Disruption in Banking Millennials are pushing companies to the edge, when it comes to customer experience. Competition is getting 5 Commercial Lending Resurgence stiff, with startups eating away your market share. And the workforce is demanding anytime anywhere work flexibility. Mobile Imaging Technology 8 Changes the Face of Banking So, what is it that as a bank you could do to ride this wave of transformation? Newgen Product Portfolio 11 This edition of our research based newsletter talks about Research from Gartner: 12 just that. The article on ‘Banking 2020’ gives you a sneak-peek into what the future looks like Hype Cycle for Digital Banking and what all you need to do to be prepared. There is a link to an interesting video in the article, Transformation, 2015 which you must watch. The article on ‘Commercial Lending Resurgence’ talks about the need to balance risk management with customer experience in today’s times. We also take a look About Newgen 47 at how Mobile Imaging technology can empower your field force to be more efficient and Newgen at a Glance 48 productive. Newgen has helped many of its global clients become market leaders through innovative solutions. We have over 200 banking clients from all across the globe. -

1 GALE Phase 3 Arabic Broadcast News Speech Part 1 1. Introduction

GALE Phase 3 Arabic Broadcast News Speech Part 1 1. Introduction GALE Phase 3 Arabic Broadcast News Speech Part 1 contains approximately 132 hours of Arabic broadcast news speech collected in 2007 by the Linguistic Data Consortium (LDC), MediaNet, Tunis, Tunisia and MTC, Rabat, Morocco during Phase 3 of the DARPA GALE program. Broadcast audio for the DARPA GALE (Global Autonomous Language Exploitation) program was collected at LDC’s Philadelphia, PA USA facilities and at three remote collection sites: Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST), Hong Kong (Chinese); Medianet (Arabic); and MTC (Arabic). The combined local and outsourced broadcast collection supported GALE at a rate of approximately 300 hours per week of programming from more than 50 broadcast sources for a total of over 30,000 hours of collected broadcast audio over the life of the program. The broadcast news recordings in this release feature news broadcasts focusing principally on current events from the following sources: Abu Dhabi TV, a television station based in Abu Dhabi, Al Alam News Channel, based in Iran; Al Arabiya, a news television station based in Dubai; Al Iraqiyah, an Iraqi television station; Aljazeera , a regional broadcaster located in Doha, Qatar; Al Ordiniyah, a national broadcast station in Jordan; Dubai TV, a broadcast station in the United Arab Emirates; Kuwait TV, a national broadcast station in Kuwait; Lebanese Broadcasting Corporation, a Lebanese television station; Nile TV, a broadcast programmer based in Egypt, Saudi TV, a national television station based in Saudi Arabia; and Syria TV, the national television station in Syria. 2. Broadcast Audio Data Collection Procedure LDC’s local broadcast collection system is highly automated, easily extensible and robust and capable of collecting, processing and evaluating hundreds of hours of content from several dozen sources per day. -

Mr Hani Fadayel Mr Mohammed Layas Shaikh Saleh Abdulla Kamel

SN Full Name 1 Mr Hani Fadayel 2 Mr Mohammed Layas 3 Shaikh Saleh Abdulla Kamel 4 Mr Khalid Al Bustani 5 Dr Saleh Al Humaidan 6 Gary S Long 7 Mr A K Sankar 8 Mr Adel Fakhro 9 Mr Ubaydli Ubaydli 10 Mr Ali Ben Yousuf Fakhro 11 Mr Ebrahim M S Al Rayes 12 Mr Anwar Khalifa Ibrahim Al Sadah 13 Mr Peter Kaliaropoulos 14 Dr Farid Ahmed Al Mulla 15 Mr Jacob Thomas 16 Ms Omaima Ebrahim 17 Mr Peter Green 18 Mr Mehtab Ali Kazi 19 Mr Ian Levack 20 Mr Younis Jamal Al Sayed 21 Mr Ali Moosa Hussain 22 Mr Vahid Mehrinfar 23 Mr Ashok Shetty 24 HE Dr Majeed Muhsin Al Alawi 25 Mr Francois Bourgoin 26 Mr Mohammed Tariq Sadiq 27 Mr Mahdi Abdullah Al Obaidat 28 Mr Atif A Abdulmalik 29 Mr Mohammed Abdulaziz Al Jomaih 30 Mr Abdulaziz Hamad Aljomaih Al Jomaih 31 Mr Akram Miknas 32 Mr Khamis Al Muqla 33 Mr Danny Barranger 34 Mr Robert N Lewis 35 Mr Hassan Ali Radhi 36 Mr A Hamid Al Asfoor 37 Mr Bassim Mohammed Al Saie 38 Mr Jamal Mohammed Fakhro 39 Mr Suhael Ahmed 40 Mr Tony Peek 41 Mr Sami M Jalal 42 HE Shaikh A M H bin Abdallah Al Khalifa 43 Mr David Bailey 44 Mr Hassan Ali Juma 45 Mr Abdulla Ali Kanoo 46 Ms Elham Hassan 47 Ms Jenny D'Cruz 48 Mr Anthony C Mallis 49 Mr Iqbal G Mamdani 50 Mr John McIsaac 51 Mr Khalid Ali Turk 52 Mr Jamil A Wafa 53 Mr Masaud J Hayat Masoud 54 Mr Tariq Daineh 55 Mr Sonjoy Francis Monteiro 56 Mr Asad Ali Asad 57 Mohammed Ali Naki 58 Mr Ali Al Khayat 59 Mr Jacob Philip 60 Mr Adnan Abdulaziz Al Bahar 61 Mr Bader Abdulmohsen Almukhaizeem 62 Mr Bader Musaed Bader Al Sayer 63 Mr Saleem Abbas 64 Mr Mohsen Dehghani 65 Mr Mohammad M Al Jassar -

Media Industry in Dubai

An Agency of the Department of Economic Development – Government of Dubai A SMALL AND MEDIUM ENTERPRISES DEVELOPMENT PERSPECTIVE OF THE MEDIA INDUSTRY IN DUBAI The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be violation of applicable law. Dubai SME encourages the dissemination of its work and will grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. All queries should be addressed to Dubai SME at [email protected] (P.O. Box 66166, Tel:+971 4361 3000, www.sme.ae ) DUBAI SME © 2010 CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..................................................................................................................................... 3 2. INTRODUCTION TO THE REPORT ................................................................................................................. 8 INDUSTRY DESCRIPTION .................................................................................................................................................. 8 INDUSTRY STRUCTURE (KEY STAKEHOLDERS) .................................................................................................................... 10 KEY INDUSTRY DRIVERS ................................................................................................................................................ 12 3. MEDIA INDUSTRY IN DUBAI – AN OVERVIEW......................................................................................... 13 (A) GOVERNEMENT PLAN ......................................................................................................................................