The Sources for the Life of St. Francis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GIVING & DISCIPLESHIP the Catholic Community of Gloucester

The Catholic Community of Gloucester & Rockport HOLY FAMILY PARISH & OUR LADY OF GOOD VOYAGE PARISH _____________________________ A Community United in Prayer, Fellowship, and Service The Epiphany of the Lord ∙ January 8, 2017 GIVING & DISCIPLESHIP OUR PASTOR’S MESSAGE — PAGE 3 _____________________________ The Catholic Community of Gloucester & Rockport Merry Christmas! Happy New Year! All Are Welcome! 74 Pleasant Street ∙ Gloucester, Massachusetts 01930 Phone: 978-281-4820· Fax: 978-281-4964· Email: [email protected]· Website: ccgronline.com Office Hours: Monday through Friday 10:00am-4:00pm Cover Image: Detail of ‘Epiphany’ by Jody Cole | jcoleicons.com THE CATHOLIC COMMUNITY OF GLOUCESTER & ROCKPORT THE EPIPHANY OF THE LORD THE EPIPHANY OF THE LORD _____________________ THE EPIPHANY PROCLAMATION While a day like Christmas is fixed in our minds and on our calendars as December 25th, many of the important feast days of the Church Year move based on the date of Easter Sunday. Each year, Easter is scheduled for the first Sunday following the “Paschal Full Moon” and can occur between March 22nd and April 25th. In ancient times, before calendars were commonplace, most people did not know the dates for the feasts of the new liturgical year. On Epiphany Sunday, the dates were “proclaimed” during the celebration of Holy Mass. After the proclamation of the Gospel, a cantor, deacon, or lector, in keeping with the ancient practices of the Church, may announce from the ambo the moveable feasts of the new year. Dear Brothers and Sisters, know that as we have rejoiced at the Nativity of Our Lord Jesus Christ, so by leave of God’s mercy, we announce to you now the joy of his Resurrection, who is our Savior. -

Italian Sixteenth-Century Maiolica Sanctuaries and Chapels

religions Article Experiencing La Verna at Home: Italian Sixteenth-Century Maiolica Sanctuaries and Chapels Zuzanna Sarnecka The Institute of Art History, University of Warsaw, 00-927 Warszawa, Poland; [email protected] Received: 30 September 2019; Accepted: 17 December 2019; Published: 20 December 2019 Abstract: The present study describes the function of small-scale maiolica sanctuaries and chapels created in Italy in the sixteenth century. The so-called eremi encouraged a multisensory engagement of the faithful with complex structures that included receptacles for holy water, openings for the burning of incense, and moveable parts. They depicted a saint contemplating a crucifix or a book in a landscape and, as such, they provided a model for everyday pious life. Although they were less lifelike than the full-size recreations of holy sites, such as the Sacro Monte in Varallo, they had the significant advantage of allowing more spontaneous handling. The reduced scale made the objects portable and stimulated a more immediate pious experience. It seems likely that they formed part of an intimate and private setting. The focused attention given here to works by mostly anonymous artists reveals new categories of analysis, such as their religious efficacy. This allows discussion of these neglected artworks from a more positive perspective, in which their spiritual significance, technical accomplishment and functionality come to the fore. Keywords: Italian Renaissance; devotion; home; La Verna; sanctuaries; maiolica; sculptures; multisensory experience 1. Introduction During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, ideas about religious sculpture still followed two conflicting trains of thought. On the one hand, writers understood the efficacy of both sculptural and painted images at impressing the divine image onto the mind and soul of the beholder. -

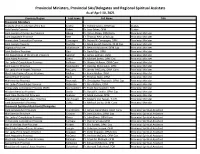

Provincial Ministers, Provincial Sas/Delegates and Regional

Provincial Ministers, Provincial SAs/Delegates and Regional Spiritual Assistats As of April 10, 2021 Province/Region Last Name Full Name Title Provincial Ministers Custody of Our Lady Star of the Sea Castro Fr. Patrick Castro, OFM Cap. Custos Holy Family Custody Grbes Fr. Jozo Grbes, OFM Custos Saint Joseph of Cupertino Province Abegg Fr. Victor Abegg, OFM Conv Provincial Minister Saint Augustine Province Betz Fr. Thomas Betz, OFM Cap. Provincial Minister Immaculate Conception Province Campagna Fr. Robert N. Campagna, OFM Provincial Minister Saint Joseph Province Costello Fr. Mark Joseph Costello, OFM Cap. Provincial Minister Stigmata Province DiSalvatore Fr. Remo DiSalvatore, OFM Cap Provincial Minister Saint Barbara Province Gaa Fr. David Gaa, OFM Provincial Minister The Assumption of the B.V.M. Province Gannon Fr. James Gannon, OFM Provincial Minister Saint Mary Province Greco Fr. Michael Greco, OFM Cap Provincial Minister Our Lady of Consolation Province Hellman Fr. Wayne Hellman, OFM Conv Provincial Minister Saint Casimir Province Malakaukis Fr. Algirdas Malakaukis, OFM Provincial Minister Our Lady of the Angels Province McCurry Fr. James McCurry, OFM Conv Provincial Minister Most Holy Name of Jesus Province Mullen Fr. Kevin Mullen, OFM Provincial Minister Sacred Heart Province Nairn Fr. Thomas Nairn, OFM Provincial Minister Mid-America Province Popravak Fr. Christopher Popravak, OFM Cap Provincial Minister Our Lady of Guadalupe Province Robinson Fr. Ron Walters, OFM Provincial Minister Immaculate Conception Province (TOR) Scornaienchi Fr. Frank Scornaienchi, TOR Provincial Minister Western America Province Snider Fr. Harold N. Snider, OFM Cap Provincial Minister Saint John the Baptist Province Soehner Fr. Mark Soehner,OFM Provincial Minister Most Sacred Heart of Jesus Province Van Tassell Fr. -

HOLY MONASTERY TOUR Our Monastery Tour Was Created to Raise

HOLY MONASTERY TOUR Our monastery tour was created to raise awareness of famous sites, sacred to the Christian religion, places of worship and stays of St. Francis of Assisi. Step back into the Middle Age, meeting and conversing with the Franciscan monks who still live in isolation and peace of the monasteries in Tuscany : LA VERNA The Sanctuary of La Verna is famous for being the place where St. Francis of Assisi would have received the stigmata September 14, 1224. Built in the southern part of Mount Penna at 1128 meters above sea level, the Sanctuary Above the cliff shrouded by forest is the largest sanctuary complex in its massive and varied architecture holds many treasures of spirituality, art, culture and history. For all Franciscans and supporters of San Francesco La Verna is an indispensable place of pilgrimage. For them, the friars of Verna centuries damage, as well as spiritual assistance, the opportunity to refresh and stop for a few days in the guest. HERMITAGE CELLS SAINT FRANCIS is a sacred building that is located in Le Celle, in the town of Cortona, in the province of Arezzo. The Franciscan settlement was founded in 1211 by the saint himself, who returned there in 1226 before he died, and was extensively restored in 1969 The complex, built at the turn of a narrow valley, is very impressive for the amenity and spirituality of the place. The dwellings of the monks and the local convent are arranged "tiers" on both sides of the valley. Finding himself to preach at Cortona in 1211, as usual, Francis asked for and obtained a place in which they can withdraw in prayer. -

'The Meek Shall Inherit the Earth' Vocations of Humility in the Early

'The Meek Shall Inherit the Earth' Vocations of humility in the early Franciscan Order Heather A. Christie A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences University of Sydney 2019 ii I certify that, to the best of my knowledge, the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work. The assistance received in preparing this thesis, and sources used, have been acknowledged. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. Heather A. Christie 19 December 2018 iii Abstract In this thesis, Francis of Assisi's vocation of humility is given its unique place in the heritage of Christian humility, and situated in relation to the early Franciscan vocation of humility that followed and the Bonaventurian vocation of humility that then concluded the infancy of First Order Franciscan development. Francis's vocation of humility was constituted by a unique blend of subjection, self- sacrifice, inversion, and freedom from worldly constraints. The characteristics that these elements gave rise to included: living the Gospel and the Rule, seeking to be the Lesser Brother in every sense, loving and honouring all brothers equally, obedience, humility in deeds and words, and the exhibition of humility that could not be mistaken for lack of strength or determination. These elements and characteristics form a framework with which to analyse the subsequent early First Order vocation of humility and the vocation of humility under Bonaventure. Studying these three vocations highlights continuities and divergences in formation and complexion. -

The Holy See

The Holy See PASTORAL VISIT TO AREZZO, LA VERNA AND SANSEPOLCRO (MAY 13, 2012) EUCHARISTIC CONCELEBRATION HOMILY OF HIS HOLINESS POPE BENEDICT XVI "Il Prato" Park, Arezzo Sunday, 13 May 2012 [Video] Dear Brothers and Sisters, It is a great joy for me to be able to break the Bread of the Word of God and of the Eucharist with you. I extend my cordial greetings to you all and I thank you for your warm welcome! I greet your Pastor, Archbishop Riccardo Fontana, whom I thank for his kind words of welcome, the other Bishops, priests, men and women religious and the representatives of Ecclesial Associations and Movements. A respectful greeting goes to the Mayor, Mr Giuseppe Fanfani, grateful for his greeting, to Senator Mario Monti, Prime Minister of Italy, and to the other civil and military Authorities. A special thank you to all those who have generously cooperated to make my Pastoral Visit a success. Today I am welcomed by an ancient Church: expert in relations and well-deserving in her commitment to building through the centuries a city of man in the image of the City of God. In the land of Tuscany, the community of Arezzo has distinguished itself many times throughout history by its sense of freedom and its capacity for dialogue among different social components. Coming among you for the first time, my hope is that this City may always understand how to make the most of this precious legacy. In past centuries, the Church in Arezzo has been enriched and enlivened by many expressions of the Christian faith, among which the highest is that of the Saints. -

Papal Overlordship and Protectio of the King, C.1000-1300

1 PAPAL OVERLORDSHIP AND PROTECTIO OF THE KING, c.1000-1300 Benedict Wiedemann UCL Submitted for the degree of PhD in History 2017 2 I, Benedict Wiedemann, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 Papal Overlordship and Protectio of the King, c.1000-1300 Abstract This thesis focuses on papal overlordship of monarchs in the middle ages. It examines the nature of alliances between popes and kings which have traditionally been called ‘feudal’ or – more recently – ‘protective’. Previous scholarship has assumed that there was a distinction between kingdoms under papal protection and kingdoms under papal overlordship. I argue that protection and feudal overlordship were distinct categories only from the later twelfth and early thirteenth centuries. Before then, papal-royal alliances tended to be ad hoc and did not take on more general forms. At the beginning of the thirteenth century kingdoms started to be called ‘fiefs’ of the papacy. This new type of relationship came from England, when King John surrendered his kingdoms to the papacy in 1213. From then on this ‘feudal’ relationship was applied to the pope’s relationship with the king of Sicily. This new – more codified – feudal relationship seems to have been introduced to the papacy by the English royal court rather than by another source such as learned Italian jurists, as might have been expected. A common assumption about how papal overlordship worked is that it came about because of the active attempts of an over-mighty papacy to advance its power for its own sake. -

La Verna La Rassina Arezzo

N highway. SS208 the on continue and Stefano Santo Pieve to up highway reached Bibbiena continue on the SS208 highway. From the Romagna side take the E45 E45 the take side Romagna the From highway. SS208 the on continue Bibbiena reached O E and Pass Consuma to road the follow Florence From highway. SP60 the on continue Getting there: take the “Umbro-Casentinese” road from Arezzo up to Rassina and and Rassina to up Arezzo from road “Umbro-Casentinese” the take there: Getting S 10 erna Santuario de La V La 8 A Ghiacciaia S O Badia Prataglia L E M 9 A 7 L 6 L E D 5 La Beccia O Bibbiena D N O 4 F 3 2 E45 Pieve S.Stefano isita Centro V 1 erna Chiusi della V Castello Nature, history and spirituality and history Nature, La Verna La Rassina Arezzo Caprese Michelangelo Sansepolcro Verna La NATURE TRAIL NATURE NATURE TRAIL NATURE HALTING POINT 1 Where is the sea gone? From a geological perspective M. Penna of La Verna is a real exception with respect to the rest of the NATURE TRAIL territory. This massive rock consists of organic limestone and other limestone resulting from cementation of marine molluscs shells, foraminifera and nanoplancton, deposited on a seabed around 20 million years ago. Around La Verna, the landscape is characterized by gently rolling slopes of rocks mainly Welcome to La Verna clay, that belong to the geological units called Liguridae, or Ligurian Units: their sedimentation, dates from about 80 million to 60 million years ago, and took place near an ancient Ocean, said by geologists From the mystical loneliness I saw a dove taking off and flying spread out toward the valleys immensely to be placed where today is the Italian Riviera. -

E Società QUADERNI DELLA RIVISTA DEL CONSORZIO PER LA GESTIONE DELLE BIBLIOTECHE COMUNALE DEGLI ARDENTI E PROVINCIALE ANSELMO ANSELMI DI VITERBO

~i~Liotecae società QUADERNI DELLA RIVISTA DEL CONSORZIO PER LA GESTIONE DELLE BIBLIOTECHE COMUNALE DEGLI ARDENTI E PROVINCIALE ANSELMO ANSELMI DI VITERBO SIMONETTA VALTIERI La chiesa di S. Francesco a Viterbo Inserto del n. 3-4, anno V, 31 dicembre 1983, di «Biblioteca e Società» Rivista del Consorzio per la gestione delle Biblioteche Comunale degli Ardenti e Provinciale Anselmo Anselmi di Viterbo I Fig. 1) Interno della chiesa di S. Francesco a Viterbo SIMONETTA VALTIERI La chiesa di S. Francesco a Viterbo I. Presupposti storici e ilzdividuaziolze di due fasi fralzcescane Per inquadrare nel panorama forme originali), va ricordato che la sco fosse presente a Viterbo nel 1209 dell'architettura francescana la chie- Custodia Viterbese veniva come im- mentre dimorava in città Innocenzo sa di S. Francesco, caratterizzata dal- portanza subito dopo la Romana 111; una cronaca del 1262 e una testi- la notevole spazialità della sua zona nell'organizzazione della Provincia Ro- monianza dell'assisano Francesco di presbiteriale (che possiamo ritenere mana codificata da S. Bonaventura (1). Bartolo del 1335 dicono viterbese completamente conservata nelle sue La tradizione vuole che S. France- Leone, il compagno del Santo che ne Il presente saggio è stato presentato al Concorso «Studio su un monumento francescano in Italia» indetto dal Centro Francescano Santa Maria in Castello di Fara Sabina ed è stato premiato da una giuria di Storici dell'architettura e del francescanesirno.I disegni di rilievo sono stati appositamente realizzati da Marina Valtieri. Si ringraziano i Frati di S. Francesco a Viterbo, e in particolare p. Ernesto Piacentini, per aver agevolato in ogni modo le indagini e per aver messo a disposizione i materiali dell'archivio della chiesa; si ringraziano il dott. -

12 Day Pilgrimage to Northern Italy Visiting Rome, Assisi, Siena, Florence, La Verna, Padua, Venice, Stresa

12 Day Pilgrimage to Northern Italy visiting Rome, Assisi, Siena, Florence, La Verna, Padua, Venice, Stresa Spiritual Director Most Reverend Frank J. Caggiano Bishop of Bridgeport September 15th – 26th, 2018 YOUR TOUR INCLUDES: • Roundtrip Air from JFK or Newark • Deluxe Motorcoach • English Speaking Guide • 4 Star First Class Hotels • Sightseeing as per itinerary • Breakfast & Dinner Daily (except in Florence where dinner is on your own) • Daily Mass and Rosary Highlights: • Visit the Basilicas of Rome – St. Peters', St. Mary Major, St. John Lateran and St. Paul Outside the Walls • Welcome Dinner at Da Meo Patacca • Visit the Basilicas of St. Francis of Assisi and St. Clare • Basilica of St. Domenic also known as Basilica Cateriniana • Visit La Verna – where St. Francis received the Stigmata • Visit the Basilica of St. Anthony of Padua • Tour of Venice • Visit the Basilica of St. Mark • Visit the Church of St. Lucy to see her body PILGRIMAGE PRICE: $ 3,699.00 per person Double or Triple $ 750.00 Single Supplement ITINERARY Sat, Sep 15th: New York/Rome Depart Newark or JFK Airport on your overnight flight to Rome. Sun, Sep 16th: Rome Upon arrival in Rome we are transferred to our hotel. Remainder of the day is free. Mon, Sep 17th: Tour of the Basilicas of Rome and Welcome Dinner Today we visit the four major Basilicas of Rome. St. Peters', St. Mary Major, St. John Lateran and St. Paul Outside the Walls. This evening we have a Welcome Dinner at Da Meo Patacca. Tue, Sep 18th: Rome Free day to enjoy Rome on your own. -

"Pure Heresy" by Adriano Petta

Adriano Petta Pure Heresy historical novel originally published in Italy in December 2005 under the title Eresia Pura by STAMPA ALTERNATIVA (ISBN – 88-7226-904-0) outline & the 3 first chapters translated from the Italian by Donald Boris Hope Adriano Petta “Pure heresy” – synopsis & the 3 first chapters Outline………………….page 3 Chapter I ……………….page 11 Chapter II .………….… page 28 Chapter III …………….page 44 * * * Stampa Alternativa – Nuovi Equilibri Strada Tuscanese km 4.800 01100 Viterbo (VT) Italy Editorial director: Marcello Baraghini Commercial director: Angelo Leone [email protected] [email protected] tel. +39 0761.352277 – 0761.353485 fax +39 0761.352751 * * * Adriano Petta is a medievalist, collaborating with the expert in Catharist studies in Italy, Professor Giovanni Gonnet; and a student of the history of science. He has published two more historical novels, Roghi fatui (Stampa Alternativa, 2001) and Hypatia, scientist of Alexandria (english edition with preface by Margherita Hack by Lampi di stampa, September 2005) which, together with Pure heresy, form the trilogy developed from his studies on the conflict between Reason and Religion. He published also La cattedrale dei pagliacci (Robin, Rome, 2000, under the pseudonym James Adler), La Guerra dei fiori (Edis, Brescia, 1993), La libertà di Marusja (Gitti Europa, Milano, 1992). ([email protected] ) * * * Back Cover of Pure Heresy The heresy of the Cathars, the “Pure”, was the bane of the papacy at the dawn of the second millennium. Determined to became the greatest power in the western world, the catholic church decided with cold resolution to prevent the spread of learning – whether religious, philosophical or scientific – and to exterminate whoever might oppose its great project. -

Influence of Joachim in the 13Th Century

THE INFLUENCE OF JOACHIM IN THE 13TH CENTURY Frances Andrews The end of the 12th century was one of the periods of great eschatological potential in the medieval Latin west. In October 1187 Jerusalem was lost to a Kurdish sultan, Saladin, and the Crusade campaigns which followed were catastrophic. Tensions between the English and French crowns were at a peak, and in June 1190 the western Emperor, Frederick I Barbarossa, drowned in the river Göksu (Saleph) on his way to the Holy Land. Things were no better in the Iberian peninsula: in July 1195 the Almohad Muslim prince Ya ‘qub I al-Mansur (the victorious) defeated the Christian King Alfonso VIII of Castille at the Battle of Alarcos. It was against this unstable background that Joachim, in the preface to his Liber de Concordia, wrote of his self-chosen role in preparing the Church in the face of the enemy:1 Our [task] is to foresee wars, yours is to hasten to arms. It is for us to go up to the watchtower on the mountain and, having seen the enemy, to give warning; yours, having heard the signal, is to take refuge in safer places. We, although unworthy scouts, witnessed long ago that the said wars would come. Would that you were worthy soldiers of Christ! “Let 1 For a chronology of his works as then known, see Kurt-Victor Selge, “L’origine delle opere di Gioacchino da Fiore,” in L’attesa della fine dei tempi nel medioevo, eds. Ovidio Capitani and Jürgen Miethke (Annali dell’Istituto storico italo-germanico Quaderno, 28) (Bologna, 1990), pp.