Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 5 of the 2020 Antelope, Deer and Elk Regulations

WYOMING GAME AND FISH COMMISSION Antelope, 2020 Deer and Elk Hunting Regulations Don't forget your conservation stamp Hunters and anglers must purchase a conservation stamp to hunt and fish in Wyoming. (See page 6) See page 18 for more information. wgfd.wyo.gov Wyoming Hunting Regulations | 1 CONTENTS Access on Lands Enrolled in the Department’s Walk-in Areas Elk or Hunter Management Areas .................................................... 4 Hunt area map ............................................................................. 46 Access Yes Program .......................................................................... 4 Hunting seasons .......................................................................... 47 Age Restrictions ................................................................................. 4 Characteristics ............................................................................. 47 Antelope Special archery seasons.............................................................. 57 Hunt area map ..............................................................................12 Disabled hunter season extension.............................................. 57 Hunting seasons ...........................................................................13 Elk Special Management Permit ................................................. 57 Characteristics ..............................................................................13 Youth elk hunters........................................................................ -

Arch Western Resources, LLC (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, DC 20549 FORM 10-K Annual Report Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2010 Commission file number: 333-107569-03 Arch Western Resources, LLC (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 43-1811130 (State or other jurisdiction (I.R.S. Employer of incorporation or organization) Identification Number) One CityPlace Drive, Ste. 300, St. Louis, Missouri 63141 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (314) 994-2700 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: None Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes o No ☑ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ☑ No o Indicate by check mark whether the registrant: (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes o No ☑ (Note: As a voluntary filer not subject to the filing requirements of Section 13 or 15(d) of the Exchange Act, the registrant has filed all reports pursuant to -

View Draft Regulation

Chapter 5, Antelope Hunting Seasons At the time of this filing, the 2020 antelope harvest information is not yet available to the Department. Individual hunt area regular hunting season dates, special archery hunting season dates, hunt area limitations, license types and license quotas may be modified after harvest data has been evaluated. Any additional proposed changes to regular hunting season dates, special archery hunting season dates, hunt area limitations, numbers of limited quota licenses, license types, hunt area boundaries or modifications to other hunting provisions shall be made available for public comment on the Department website. An updated draft of 2021antelope hunting season proposals will also be posted to the Department website during the later portion of the public comment period. Section 4, edits have been proposed to further clarify antelope hunting season provisions for persons who qualify for and are in possession of hunting season extension permits. During the 2020 hunting season, special archery season information was repositioned within this regulation and caused some confusion among hunting season extension permit holders. The edited language in this Section is meant to clarify when a hunting season extension permit is valid. Please scroll down to view the regulation or click the down arrow for the next page. Draft 1-25-2021.2 CHAPTER 5 ANTELOPE HUNTING SEASONS Section 1. Authority. This regulation is promulgated by authority of Wyoming Statutes § 23-1-302, § 23-1-703 and § 23-2-104. Section 2. Regular Hunting Seasons. Hunt areas, season dates and limitations. Special Archery Regular Hunt License Dates Season Dates Area Type Opens Closes Opens Closes Quota Limitations 1 1 Aug. -

Arch Coal, Inc. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, DC 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Date of report (Date of earliest event reported): March 23, 2009 (March 23, 2009) Arch Coal, Inc. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 1-13105 43-0921172 (State or other jurisdiction of (Commission File Number) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) incorporation) CityPlace One One CityPlace Drive, Suite 300 St. Louis, Missouri 63141 (Address, including zip code, of principal executive offices) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (314) 994-2700 Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of the following provisions: o Written communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425) o Soliciting material pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a-12) o Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 14d-2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d-2(b)) o Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 13e-4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e-4(c)) Item 7.01 Regulation FD Disclosure. On March 23, 2009, John Eaves, President and Chief Operating Officer of Arch Coal, Inc., will deliver a presentation at the Howard Weil 37th Annual Energy Conference that will include written communication comprised of slides. The slides from the presentation are attached hereto as Exhibit 99.1 and are hereby incorporated by reference. -

Kerr-Mcgee Coal V. Sol (Msha) (91121889)

CCASE: KERR-MCGEE COAL V. SOL (MSHA) DDATE: 19911209 TTEXT: ~1889 Federal Mine Safety and Health Review Commission (F.M.S.H.R.C.) Office of Administrative Law Judges KERR-MCGEE COAL CORPORATION, CONTEST PROCEEDINGS CONTESTANT Docket No. WEST 91-84-R v. Citation No. 3242337; 10/25/90 SECRETARY OF LABOR, Docket No. WEST 91-85-R MINE SAFETY AND HEALTH Order No. 3242340; 10/25/90 REVIEW ADMINISTRATION, RESPONDENT Jacobs Ranch SECRETARY OF LABOR, CIVIL PENALTY PROCEEDING MINE SAFETY AND HEALTH REVIEW ADMINISTRATION, Docket No. WEST 91-220 PETITIONER A.C. No. 48-00997-03513 v. Jacobs Ranch KERR-MCGEE COAL CORPORATION, RESPONDENT DECISION Appearances: Margaret A. Miller, Esq., Office of the Solicitor, U.S. Department of Labor, Denver, Colorado, for Respondent/Petitioner; Charles W. Newcom, Esq., SHERMAN & HOWARD, Denver, Colorado, for Contestant/Respondent. Before: Judge Lasher These three consolidated contest/civil penalty proceedings came on for hearing in Denver, Colorado, on July 23, 1991. Kerr-McGee Corporation (herein "K-M") in two contests challenges Citation No. 3242337 issued on October 25, 1990, by MSHA Inspector Jimmie Giles1 charging a violation of 30 C.F.R. 40.4 and ~1890 104(b) "failure to abate" Withdrawal Order No. 3242340 issued approximately 10 to 20 minutes after the Citation was issued. The Secretary of Labor (herein "MSHA") in the related penalty proceeding captioned seeks assessment of a penalty for the violation alleged in the citation. Contentions of the Parties The general issues are whether K-M violated 30 C.F.R. Part 40.4 and 103(f) of the Act by failing to post the designation of representative of miners (in the record three times as Exhibits K-1, M-1, and A-1 to the stipulation) and, if so, the appropriate amount of penalty for such violation. -

FINAL Environmental Impact Statement for the West Antelope II Coal Lease Application WYW163340

BLM FINAL Environmental Impact Statement for the West Antelope II Coal Lease Application WYW163340 Volume 2 of 2 Appendices Wyoming State Office – Casper Field Office Field Casper – Office State Wyoming December 2008 MISSION STATEMENT It is the mission of the Bureau of Land Management to sustain the health, diversity, and productivity of the public lands for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations. BLM/WY/PL-09/011+1320 Table of Contents VOLUME 2 LIST OF APPENDICES Appendix A. Federal and State Agencies and Permitting Requirements Appendix B. Unsuitability Criteria for the West Antelope II LBA Tract Appendix C. Coal Lease-by-Application Flow Chart Appendix D. BLM Special Coal Lease Stipulations and Form 3400-12 Coal Lease Appendix E. CBNG Wells Capable of Production Appendix F. Supplemental Air Quality Information Appendix G. Non-Mine Groundwater and Surface Water Rights Appendix H. USDA-FS Region 2 Sensitive Species and Management Indicator Species and BLM Sensitive Species Evaluation for the West Antelope II Coal Lease Application EIS Appendix I. Biological Assessment Appendix J. Comment Letters on the Final EIS and Response Final EIS, West Antelope II Coal Lease Application i APPENDIX A FEDERAL AND STATE PERMITTING REQUIREMENTS AND AGENCIES Appendix A APPENDIX A: FEDERAL AND STATE AGENCIES & PERMITTING REQUIREMENTS Agency Lease/Permit/Action FEDERAL Bureau of Land Management Coal Lease Resource Recovery & Protection Plan Scoria Sales Contract Exploration Drilling Permit Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Preparation -

August 1, 2001

3425 WYW146744 FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT FOR THE NORTH JACOBS RANCH COAL LEASE APPLICATION WYW146744 N O T I C E On August 8, 2001, the Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) for the North Jacobs Ranch Coal Lease Application, Serial Number WYW146744, was provided to the public for review. On August 24, 2001, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) will publish its 30-day notice of availability in the Federal Register. The Bureau of Land Management will accept comments on this FEIS thru September 24, 2001. Comments received during the EPA notice of availability period will be considered in preparing the Record of Decision. Please send written comments to Bureau of Land Management, Casper Field Office, Attn: Nancy Doelger, 2987 Prospector Drive, Casper, WY 82604. Written comments may also be e-mailed to the attention of Nancy Doelger at “[email protected].” E-mail comments must include the name and mailing address of the commentor to receive consideration. Written comments may also be faxed to 307-261-7587. Comments, including names and street addresses of respondents, will be available for public review at the Bureau of Land Management, Casper Field Office, 2987 Prospector Drive, Casper, Wyoming, during regular business hours (8 a.m. to 4:30 p.m.), Monday through Friday, except holidays. Individual respondents may request confidentiality. If you wish to withhold your name or street address from public review or from disclosure under the Freedom of Information Act, you must state this prominently at the beginning of your written comment. Such requests will be honored to the extent allowed by law. -

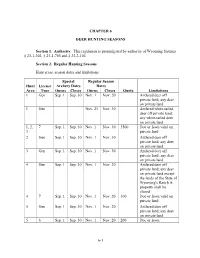

Deer Season Subject to the Species Limitation of Their License in the Hunt Area(S) Where Their License Is Valid As Specified in Section 2 of This Chapter

CHAPTER 6 DEER HUNTING SEASONS Section 1. Authority. This regulation is promulgated by authority of Wyoming Statutes § 23-1-302, § 23-1-703 and § 23-2-104. Section 2. Regular Hunting Seasons. Hunt areas, season dates and limitations. Special Regular Season Hunt License Archery Dates Dates Area Type Opens Closes Opens Closes Quota Limitations 1 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land 1 Gen Nov. 21 Nov. 30 Antlered white-tailed deer off private land; any white-tailed deer on private land 1, 2, 7 Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 30 3500 Doe or fawn valid on 3 private land 2 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 30 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land 3 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 30 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land 4 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land except the lands of the State of Wyoming's Ranch A property shall be closed 4 7 Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 300 Doe or fawn valid on private land 5 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land 5 6 Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 200 Doe or fawn 6-1 6 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land 7 Gen Sep. -

Powder River Basin Coal Resource and Cost Study George Stepanovich, Jr

Exhibit No. MWR-1 POWDER RIVER BASIN COAL RESOURCE AND COST STUDY Campbell, Converse and Sheridan Counties, Wyoming Big Horn, Powder River, Rosebud and Treasure Counties, Montana Prepared For XCEL ENERGY By John T. Boyd Company Mining and Geological Consultants Denver, Colorado Report No. 3155.001 SEPTEMBER 2011 Exhibit No. MWR-1 John T. Boyd Company Mining and Geological Consultants Chairman James W Boyd October 6, 2011 President and CEO John T Boyd II File: 3155.001 Managing Director and COO Ronald L Lewis Vice Presidents Mr. Mark W. Roberts Richard L Bate Manager, Fuel Supply Operations James F Kvitkovich Russell P Moran Xcel Energy John L Weiss 1800 Larimer St., Suite 1000 William P Wolf Denver, CO 80202 Vice President Business Development Subject: Powder River Basin Coal Resource and Cost Study George Stepanovich, Jr Managing Director - Australia Dear Mr. Roberts: Ian L Alexander Presented herewith is John T. Boyd Company’s (BOYD) draft report Managing Director - China Dehui (David) Zhong on the coal resources mining in the Powder River Basin of Assistant to the President Wyoming and Montana. The report addresses the availability of Mark P Davic resources, the cost of recovery of those resources and forecast FOB mine prices for the coal over the 30 year period from 2011 Denver through 2040. The study is based on information available in the Dominion Plaza, Suite 710S 600 17th Street public domain, and on BOYD’s extensive familiarity and experience Denver, CO 80202-5404 (303) 293-8988 with Powder River Basin operations. (303) 293-2232 Fax jtboydd@jtboyd com Respectfully submitted, Pittsburgh (724) 873-4400 JOHN T. -

Cutting Subsidies and Closing Loopholes in the U.S. Department of the Interior’S Coal Program by Matt Lee-Ashley and Nidhi Thakar January 6, 2015

Cutting Subsidies and Closing Loopholes in the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Coal Program By Matt Lee-Ashley and Nidhi Thakar January 6, 2015 In 2002, the Powder River Basin, or PRB, in Wyoming and Montana surged past the Appalachian coalfields that stretch from Pennsylvania to Tennessee to become the nation’s largest coal-producing region.1 Today, the PRB occupies a 40 percent share of the U.S. coal market.2 Although market forces, mechanization, and technological changes help explain some of the coal industry’s decision to shift more production from privately owned lands in the East to federal lands in the American West, the U.S. Department of the Interior’s, or DOI’s, coal policies have played an equally important— though largely unnoticed—role in this transition. Specifically, the DOI’s Bureau of Land Management, or BLM, and Office of Natural Resources Revenue, or ONRR, use their royalty-collection authority to subsidize coal pro- duction on federal lands. Coal companies, in turn, have learned to maximize these subsi- dies by shielding themselves from royalty payments through increasingly complex financial and legal mechanisms. Reform is urgently needed to cut these subsidies and to close loopholes that disadvantage other coal producing regions and distort U.S. energy markets. Subsidizing federal coal through royalty relief The law governing royalty payments for coal produced on federally owned lands is straightforward. Under the Mineral Leasing Act of 1920 and its amendments, coal com- panies are required to pay a royalty of at least 12.5 percent of the value of surface-mined coal and 8 percent for coal from underground mines.3 The law authorizes the secretary of the interior to set the regulations by which the value of federal coal is determined for calculating a royalty. -

Msha) (93030352

CCASE: KERR-McGEE COAL V. SOL (MSHA) DDATE: 19930304 TTEXT: ~352 March 4, 1993 KERR-McGEE COAL CORPORATION : : v. : Docket Nos. WEST 91-84-R : WEST 91-85-R SECRETARY OF LABOR, : WEST 91-220 MINE SAFETY AND HEALTH : ADMINISTRATION (MSHA) : BEFORE: Holen, Chairman; Backley, Doyle, and Nelson, Commissioners DECISION BY THE COMMISSION: This consolidated contest and civil penalty proceeding arises under the Federal Mine Safety and Health Act of 1977, 30 U.S.C. 801 et seq. (1988)(the "Mine Act" or "Act"), and presents the issue of whether miners may choose as their representative for "walkaround" purposes under section 103(f) of the Mine Act,(Footnote 1) a union, or the agent of a union, that is not the miners' collective bargaining representative under the National Labor Relations Act, 29 U.S.C. 151 et seq. (as amended)(1988)("NLRA"). This case arose when an inspector from the Department of Labor's Mine Safety and Health Administration ("MSHA") issued to Kerr-McGee Coal Corporation ("Kerr-McGee") a citation alleging that Kerr-McGee had violated 30 C.F.R. 40.4 when it failed to post at its Jacobs Ranch Mine, a nonunion mine, the names of certain miners' representatives not employed by Kerr-McGee. These individuals were agents of _________ 1 The term "walkaround" is used in reference to the rights granted miners' representatives under section 103(f) of the Mine Act, which provides in pertinent part: Subject to regulations issued by the Secretary, a representative of the operator and a representative authorized by his miners shall be given an opportunity to accompany the Secretary or his authorized representative during the physical inspection of any coal or other mine .. -

National Mining Association 2006 Coal Producer Survey • May 2007

National Mining Association 2006 Coal Producer Survey • May 2007 2006 COAL PRODUCER SURVEY May 2007 Compiled by: Leslie L. Coleman (202) 463-9780 E-mail: [email protected] NATIONAL MINING ASSOCIATION 101 Constitution Avenue, NW Suite 500 East Washington, D.C. 20001 (202) 463-2600 www.nma.org THE NATIONAL MINING ASSOCIATION 2006 COAL PRODUCER SURVEY May 2007 The Coal Industry In 2006 Production – Coal production in the United States reached record levels again in 2006, increasing by 29.9 million short tons, or 2.6 percent from the prior year, to 1,161.4 million short tons, according to preliminary government figures. In 2006, eastern coal (east of the Mississippi River) accounted for 42.1 percent of production (489.5 million tons including refuse recovery). Production in the West reached 57.9 percent (671.9 million tons). Eastern coal production was down 0.9 percent over 2005, with the only Eastern state increases coming from Indiana, Kentucky, Virginia and Illinois. In the Appalachian region, particularly central Appalachia, difficult mining conditions are beginning to impact production. Some of the decrease in Appalachian coal production was offset by increases in Powder River Basin coal, imports and some Illinois Basin coal. Production in the West, led by Wyoming, was up 5.4 percent. In addition to Wyoming, production from Utah, Montana and North Dakota increased over 2005. While, production in 2007 is expected to approximate 2006, actual 2007 production will be dependent on increasing coal consumption and the speed at which above normal inventories are reduced. Western coal production, primarily from the Powder River basin, will continue to increase in 2007.