The End of the Beginning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saints & Sinners: Joseph of Arimathea

SAINTS & SINNERS: JOSEPH OF ARIMATHEA March 24 2021 I Corinthians 15:12-26 John 19:31-42 In the holy name of Jesus, Amen. For our Lord’s birth and early life, God the Father provided a man named of Joseph. A righteous, pious man who would raise the little baby Jesus in the knowledge of the Scriptures and instill in Him the disciplines of a devout, religious life. Namely, the practice of morning and evening prayer, the routine of attending synagogue each week, as well as making regular pilgrimages to Jerusalem throughout the year. So, every day, once a week, and special times throughout the year, Joseph taught Jesus to turn His attention toward God and the truths of God. All of this, along with our Lord’s carpentry skills, Jesus learned from Joseph. For our Lord’s death, God the Father provided another Joseph, who was not our Lord’s teacher, as the first Joseph was, but rather, was one of our Lord’s disciples, a learner of Jesus. Joseph of Arimathea. This Joseph was a respected member of the Sanhedrin, the Jewish religious council in Jerusalem, that at times, was a source of consternation for our Lord during His earthly ministry. Just listen to how St. Paul, who wasn’t a member of the Sanhedrin, but he clearly was on track to become one, that is, if the resurrected Jesus hadn’t met him on the Road to Damascus. Listen to how St. Paul described those of this elite religious, ruling class— they have a zeal for God, but not according to knowledge. -

Joseph of Arimathea

FACES OF OUR FAITH QUEEN VASHTI read ESTHER 1-2:17 FACES OF OUR FAITH from theJOSEPH artist |OF HANNAH ARIMATHEA GARRITY Having the bravery and confidence to stand up to an inappropriate request from a superior is both paramount read LUKE 23:44-56 to the moral foundation of society, and extremely di!fromicult. We the each artist know deep| HANNAH down when GARRITY we are doing rightHow or wrong.heavy is the body of a dead man? Only with In thissuperhuman text, Vashti’s strength modesty would and this fearlessness pose be possible. resonated Yet, withJoseph me. I imagined of Arimathea her recognizingalone carries that Jesus’ her lifelesshusband’s body. demandHow did for heher do to it?show Why her did beauty he do toit? hisLuke drunken says, “He friends came oversteppedfrom the Jewish his bounds. town of Arimathea, and he was waiting expectantly for the kingdom of God” (Luke 23:51). Is this Heract simple good reply, enough? “no,” is feared by the male “sages who knew the laws” (Esther 1:13). They advise the king to cast QueenHe was Vashti on outthe andcouncil. to replace He disagreed her with with a new the queen. majority. Why could he not stop the crucifixion from happening Herein Ithe have first represented place? Why Vashti did he dancing fail to convince alone. I seehis fellowher livingcouncil into her members? refusal withIs this grace good and deed beauty, enough exhibiting to make up independencefor such a monumental and strength failure? in her solitary righteousness. Or is Joseph of Arimathea at the right place at the right time? Is he able to dignify Jesus’ body a!er death? Does he play the vital role of the dissenter, picking up the pieces of the wrongs of the group? Does Joseph forward God’s plan for Jesus’ death and resurrection? How weighty a task. -

Luke Bible Study

Luke: One Man for All Mankind The Beloved Physician I. Introduction by HEROD ANTIPAS. HEROD AGRIPPA A. History I died, eaten of worms, at age 54. 1. Timeline (A.D.) 1 45 PAUL, BARNABAS and JOHN MARK 36 STEPHEN was stoned to death, visited Jerusalem from Antioch. JAMES becoming the first Christian martyr. SAUL wrote his epistle. MATTHEW went to (PAUL the Apostle) was converted on the Persia. road to Damascus. PONTIUS PILATE was 46 PAUL was at Antioch. sent to Rome for misadministration. 48 PAUL and BARNABAS began their first Figure 1: Icon of St. missionary journey. Luke 49 THOMAS, JUDE 37 PAUL was at and BARTHOLOMEW Damascus. The first went to India where church in Europe was they ministered in started in Glastonbury, Nisibis, Malebar, England by JOSEPH of Socotora, Camboia and Arimathea. FLAVIUS Mogar. They even went JOSEPHUS was born. to Cataio, Bisnaga and 38 PAUL fled from China. Damascus, went to 50 PAUL and Jerusalem, then to BARNABAS attended Tarsus. the Council at 39 JOSEPH of Jerusalem. MATTHEW Arimathea and SIMON wrote his gospel. ZELOTES went to 51 PAUL and SILAS Avalon in Britain and began a second established a church missionary journey. there. PAUL met the Gentile 40 IGNATIUS physician, LUKE at succeeded SIMON Troas. BARNABAS PETER at Antioch. and JOHN MARK 43 London was founded. ministered in Syria and Cilicia. 44 PAUL was at Antioch. The disciples of 52 PAUL wrote “First Thessalonians” from Christ were first called “Christians” at Corinth. THOMAS was killed in Antioch. SIMON PETER went to Caesarea Cranganore, India by Brahmin priests who from Joppa and CORNELIUS was knocked him to the ground and stuck him converted. -

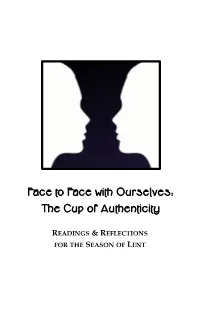

Face to Face with Ourselves: the Cup of Authenticity

Face to Face with Ourselves: The Cup of Authenticity READINGS & REFLECTIONS FOR THE SEASON OF LENT Lent 2019 Lent A Season of Spiritual Reflection In the early Church, candidates for baptism spent the 40 days prior to Easter Sunday preparing for their baptisms by fasting and studying Christian doctrines.* The contemporary questions, “What are you giving up for Lent?” is an expansion of giving up food during fasting. The 40 days of preparation in Lent reflected the 40 days Jesus spent in the wilderness preparing for his earthly ministry by fasting and facing the central temptations of his life with the truth of scripture. Lent calls us to remember the interiority of spirituality amidst lifestyles that can easily become focused on the external wrappings and trappings of life. Lent is an annual reminder that spiritual conversion is a continual process. Lent is a word deriving from an Anglo-Saxon term, “lencten,” meaning spring. The word lencten signified the lengthening of daylight hours in Spring. The Christian season of Lent was initiated by the early Church to refer to the transformation from Winter to Spring, cold to warmth, dormancy to life. Just as the inward transformation of nature occurs during winter in preparation for the brilliance and new growth of Spring, the focus theme of Lent reminded believers that outward signs of life in Christ result from inward obedience to the Spirit. As a diverse community of Christians, rooted in Baptist principles, yet representative of several Christian denominational traditions, St. John’s will walk through the seasons of Lent focusing on preparation and transformation. -

Good Friday Way of the Cross 2021 St. Gabriel Catholic Church

FIRST STATION Jesus is condemned to death. Guide: We adore You, O Christ, and we praise You. All: Because, by Your holy cross, You have redeemed the world. From the Gospel according to Mark (15:14-15) The crowd shouted all the more, “Crucify him”. So Pilate, wishing to satisfy the crowd, released for them Barabbas; and having scourged Jesus, he delivered him to be crucified. Good Friday Way of the Cross 2021 MEDITATION St. Gabriel Catholic Church Pilate’s verdict was pronounced under pressure from the priests and Meditation Texts are from St. John Paul II, Via Crucis in Rome 2003. the crowd. The sentence of death by crucifixion was meant to calm their fury and meet their clamorous demand: “Crucify him! Crucify Opening Prayer him!” (Mk 15:13-14). The Roman praetor thought he could dissociate himself from the sentence, washing his hands of it, just as he had Lord Jesus, already distanced himself from Christ’s words identifying his King- At your birth you came to share our nature. dom with the truth, and with witness to the truth (Jn 18:38). In both In your Passion and death you shared our pains and sorrows. instances Pilate was trying to preserve his own independence, to Through our meditation on the sufferings you endured for our salvation remain somehow “uninvolved”. So it may have seemed to him, on the may we share your rejection of sin surface. But the Cross to which Jesus of Nazareth was condemned and your life of commitment (Jn 19:16), like the truth he told about his Kingdom (Jn 18:36-37), had to God and neighbor. -

People of the Passion: the Rich Man March 28, 2021 Dr

People of the Passion: The Rich Man March 28, 2021 Dr. Tom Pace Matthew 27:57-61 When it was evening, there came a rich man from Arimathea, named Joseph, who was also a disciple of Jesus. He went to Pilate and asked for the body of Jesus; then Pilate ordered it to be given to him. So Joseph took the body and wrapped it in a clean linen cloth and laid it in his own new tomb, which he had hewn in the rock. He then rolled a great stone to the door of the tomb and went away. Mary Magdalene and the other Mary were there, sitting opposite the tomb. Matthew 27:57-61 (NRSV) Let’s pray together. Oh God, open us up today to whatever it is that you have for us to receive in this message. Open our eyes that we might see and open our ears that we might hear your word in the midst of these words, and open our hearts, God, that we might have compassion and that your word might fall into our hearts. And then, O Lord, open our hands that we might serve. Amen. I don’t know if you’ve ever had the challenge or opportunity or maybe the privilege to plan a memorial service for someone you love - to make the arrangements, as the saying goes. It can be a really daunting task where you head into the funeral home to meet with the folks there. It seems like it shouldn’t be that hard, but there are so many decisions, and they’re coming at you so fast. -

All in the Family 5: Joseph of Arimathea Sermon by Rev

July 28, 2013 All in the Family 5: Joseph of Arimathea Sermon by Rev. Robert English John 19:38-42 After these things, Joseph of Arimathea, who was a disciple of Jesus, though a secret one because of his fear of the Jews, asked Pilate to let him take away the body of Jesus. Pilate gave him permission; so he came and removed his body. Nicodemus, who had at first come to Jesus by night, also came, bringing a mixture of myrrh and aloes, weighing about a hundred pounds. They took the body of Jesus and wrapped it with the spices in linen cloths, according to the burial custom of the Jews. Now there was a garden in the place where he was crucified, and in the garden there was a new tomb in which no one had ever been laid. And so, because it was the Jewish day of Preparation, and the tomb was nearby, they laid Jesus there. Today is the fifth Sunday in our summer sermon series ‘All in the Family.’ Each week Rev. Patricia has been focusing on lesser known followers of Jesus from the New Testament- lifting up for us today different models of discipleship. Rev. Patricia mentioned before that she drew the name from the famous television show as the inspiration for the title of our summer sermon series. Now I am from a different generation and have never seen an episode of ‘All in the Family.’ In fact I only know the television show by its name and the name of some of its iconic characters. -

History of Joseph of Arimathea”

"PROOFS OF ISRAEL – XXVI” “History of Joseph of Arimathea” By: The Author: Jehovah-God The Recorder: William N. Hollis B.S., M.A., E.X. (Exhorter) MATTHEW 27:57-60: "When the even was come, there came a rich man of Arimathea, Joseph, who also himself was Jesus' disciple. He went to Pilate, and begged the body of Jesus. Then Pilate commanded the body to be delivered. And when Joseph had taken the body, he wrapped it in a clean linen cloth, And laid it in his own new tomb, which he had hewn out in the rock; and he rolled a great stone to the door of the sepulchre, and departed" MARK 15:43: "Joseph of Arimathea, an honorable counselor, which also waited for the kingdom of God, came, and went in boldly unto Pilate, and craved the body of Jesus. And Pilate marveled if he were already dead: and calling unto him the centurion, he asked him whether he had been any while dead. And when he knew it of the centurion, he gave the body to Joseph. And he bought fine linen, and took him down, and wrapped him in the linen, and laid him in a sepulchre which was hewn out of a rock, and rolled a stone unto the door of the sepulchre." LUKE 23:50-54: "And behold, there was a man named Joseph, a counselor, and he was a good man, and a just; (The same had not consented to the counsel and deed of them:) he was of Arimathea, a city of the Jews, who also himself waited for the kingdom of God. -

The Origins of the Entombment of Christ 7

The Origins of the Entombment of Christ 7 Chapter 1 The Origins of the Entombment of Christ Biblical Basis The narrative scene of the Entombment of Christ is recorded in all four Gos- pels in a rather cryptic fashion; the story is fleshed out in the apocryphal Gos- pel of Nicodemus, which is generally believed to have been composed sometime in the fourth century.1 The Synoptic Gospels feature different as- pects of the burial of Christ, including the participants who witnessed the event. Indeed, the burial of Christ seems a minor event in the history of the Passion: after Christ is crucified, Joseph of Arimathea, alone or in the company of Nicodemus, carries the body of Christ wrapped in a shroud for burial to a rocky cave. Mark (15.40–47) records that Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James the Less and of Joses, Salome, and many other women look on from afar. Joseph asks Pilate for the body of Christ and then wraps his body in fine linen and lays him in a sepulcher as Mary Magdalene and Mary mother of Joses look on: And there were also women looking on afar off: among whom was Mary Magdalen, and Mary the mother of James the Less and of Joses, and Salome: Who also when in Galilee followed him, and ministered to him, and many other women that came up with him to Jerusalem. And when evening was now come, because it was the Parasceve, that is, the day before the Sabbath, Joseph of Arimathea, a noble counselor, who was also himself looking for the kingdom of God, came and went in boldly to Pilate, and begged the body of Jesus. -

St. John the Baptist Greek Orthodox Church Mission Statement

St. John The Baptist Greek St. John The Baptist Orthodox Church Mission Statement: Greek Orthodox Church To foster the spiritual maturity of the Orthodox Christian faithful of St. John the Baptist Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America * Metropolis of San Francisco and reach out to inquirers, the unchurched and inactive Orthodox on the west side of Rev. Fr. Theodore Dorrance * Rev. Fr. Timothy Pavlatos * Dn. Innocent Duchow-Pressley metropolitan Portland through worship, the sacramental life, education, philanthropy, hospitality, fellowship and the practice of Christian Stewardship, thereby serving as an 14485 SW Walker Road, Beaverton, Oregon 97006 instrument in the growth and expansion of the Orthodox Christian Church. 503.644.7444 Fax: 503.296.2507 * [email protected] Mochas for Missions Special Drawing TODAY - Help us pick up the pace and reach our $4,000 Visit our Parish website at www.stjohngoc.org goal. Give $20 or more by 12:15p today to be entered into a drawing for a special edition red cof- Witnessing the Truth of Apostolic Christianity fee mug with Theotokos design and a bag of Fr. Michael’s Roastery coffee. The winner will be an- nounced at the end of Theology 101. ASA warmly welcomes the newest addition to our school community, Mrs. Emily Rollison (Rayl). Mrs. Rollison and her husband are relocating to Portland from Colorado so she can teach 1st & 2nd sunday of the Myrrhbearers grades at ASA this fall. ASA families and interested St. John members are invited to join us for a meet & greet this afternoon at 1:15pm in the K/1 classroom. -

Rosslyn Chapel and the Holy Grail

Discussion Topic 4 Rosslyn Chapel and the Holy Grail In the Bible, Jesus had one last meal with his disciples before he was arrested. This was called the Last Supper. At this meal, he shared bread and wine. He told his disciples about all the things which were going to happen to him. Some say that the cup he used at this meal was There are legends that the Grail has mysterious kept safe by his followers to remember the man powers. Some say that whoever drinks from it will they believed was the Son of God. live forever. This cup was called the Holy Grail. There are Some think the Grail was taken all around many stories and legends about it. Some say that Europe and that it was once guarded by the this Grail never existed, and that it was just a Knights Templar. fairy story. This story might have been made up At the end of its long travels, some believe that it by a man named Chretien de Troyes in the 12th found its final resting place in Rosslyn Chapel. century. Some believe that the Grail was also used to catch Jesus’ blood as he died on the cross. Some believe that a man called Joseph of Arimathea got hold of this cup. They say that Joseph looked after it and passed it on and that it survives to this day. The interest in the Holy Grail was limked to tales of An illustration of Joseph of Arimathea, who was related King Arthur and the Round Table. -

The Way Study Guide 23

THE WAY OF THE COMMUNITY: THE GOSPEL OF MATTHEW Chapter 23: The Empty Tomb Open with Prayer On the Resurrection of Jesus One cannot easily harmonize the four gospels to the details surrounding the resurrection of Jesus. How many women went to the tomb on Sunday morning? Mark says two, but Matthew says three, and Luke indicates there were even more. Why were the women there? Mark says they wanted to anoint the body, but Matthew makes no mention of this. How many angels were at the tomb? Luke has two, Matthew and Mark have one, and John has none! Scholars Albright and Mann put it this way: “For all the confusing chronology, for the manifest variations in tradition, the one thing upon which all four evangelists are agreed is that the tomb of Jesus was empty.” Each gospel writer then adds his perspective to this very important piece of information. Why is the tomb empty? What does it mean? Let’s investigate Matthew’s account of the resurrection for a better understanding of what he understood by the empty tomb. Burying Jesus Read Matthew 27:57-61 What details strike you about the burial of Jesus? Why do you believe Matthew included these details in his gospel? ___________________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________________ !1 Each one of the four gospels tell us that Joseph of Arimathea was responsible for burying Jesus. However, Matthew’s account is unique in the following ways: — Joseph is called “a rich man” — Joseph is explicitly called a disciple of Jesus; in the other gospels, he is merely “good and righteous” or “waiting for the kingdom of God” — nowhere is mentioned that he was a member of the Sanhedrin (religious council) — the tomb belonged to Joseph — Joseph himself had hewn the tomb out of the rock.