John Chapman Vice President

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Staff Officers of the Confederate States Army. 1861-1865

QJurttell itttiuetsity Hibrary Stliaca, xV'cni tUu-k THE JAMES VERNER SCAIFE COLLECTION CIVIL WAR LITERATURE THE GIFT OF JAMES VERNER SCAIFE CLASS OF 1889 1919 Cornell University Library E545 .U58 List of staff officers of the Confederat 3 1924 030 921 096 olin The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924030921096 LIST OF STAFF OFFICERS OF THE CONFEDERATE STATES ARMY 1861-1865. WASHINGTON: GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. 1891. LIST OF STAFF OFFICERS OF THE CONFEDERATE ARMY. Abercrombie, R. S., lieut., A. D. C. to Gen. J. H. Olanton, November 16, 1863. Abercrombie, Wiley, lieut., A. D. C. to Brig. Gen. S. G. French, August 11, 1864. Abernathy, John T., special volunteer commissary in department com- manded by Brig. Gen. G. J. Pillow, November 22, 1861. Abrams, W. D., capt., I. F. T. to Lieut. Gen. Lee, June 11, 1864. Adair, Walter T., surg. 2d Cherokee Begt., staff of Col. Wm. P. Adair. Adams, , lieut., to Gen. Gauo, 1862. Adams, B. C, capt., A. G. S., April 27, 1862; maj., 0. S., staff General Bodes, July, 1863 ; ordered to report to Lieut. Col. R. G. Cole, June 15, 1864. Adams, C, lieut., O. O. to Gen. R. V. Richardson, March, 1864. Adams, Carter, maj., C. S., staff Gen. Bryan Grimes, 1865. Adams, Charles W., col., A. I. G. to Maj. Gen. T. C. Hiudman, Octo- ber 6, 1862, to March 4, 1863. Adams, James M., capt., A. -

Civil War in the Delta: Environment, Race, and the 1863 Helena Campaign George David Schieffler University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2017 Civil War in the Delta: Environment, Race, and the 1863 Helena Campaign George David Schieffler University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Schieffler, George David, "Civil War in the Delta: Environment, Race, and the 1863 Helena Campaign" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 2426. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2426 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Civil War in the Delta: Environment, Race, and the 1863 Helena Campaign A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by George David Schieffler The University of the South Bachelor of Arts in History, 2003 University of Arkansas Master of Arts in History, 2005 August 2017 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. ____________________________________ Dr. Daniel E. Sutherland Dissertation Director ____________________________________ ____________________________________ Dr. Elliott West Dr. Patrick G. Williams Committee Member Committee Member Abstract “Civil War in the Delta” describes how the American Civil War came to Helena, Arkansas, and its Phillips County environs, and how its people—black and white, male and female, rich and poor, free and enslaved, soldier and civilian—lived that conflict from the spring of 1861 to the summer of 1863, when Union soldiers repelled a Confederate assault on the town. -

Callaway County, Missouri During the Civil War a Thesis Presented to the Department of Humanities

THE KINGDOM OF CALLAWAY: CALLAWAY COUNTY, MISSOURI DURING THE CIVIL WAR A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS By ANDREW M. SAEGER NORTHWEST MISSOURI STATE UNIVERSITY MARYVILLE, MISSOURI APRIL 2013 Kingdom of Callaway 1 Running Head: KINGDOM OF CALLAWAY The Kingdom of Callaway: Callaway County, Missouri During the Civil War Andrew M. Saeger Northwest Missouri State University THESIS APPROVED Thesis Advisor Date Dean of Graduate School Date Kingdom of Callaway 2 Abstract During the American Civil War, Callaway County, Missouri had strong sympathies for the Confederate States of America. As a rebellious region, Union forces occupied the county for much of the war, so local secessionists either stayed silent or faced arrest. After a tense, nonviolent interaction between a Federal regiment and a group of armed citizens from Callaway, a story grew about a Kingdom of Callaway. The legend of the Kingdom of Callaway is merely one characteristic of the curious history that makes Callaway County during the Civil War an intriguing study. Kingdom of Callaway 3 Introduction When Missouri chose not to secede from the United States at the beginning of the American Civil War, Callaway County chose its own path. The local Callawegians seceded from the state of Missouri and fashioned themselves into an independent nation they called the Kingdom of Callaway. Or so goes the popular legend. This makes a fascinating story, but Callaway County never seceded and never tried to form a sovereign kingdom. Although it is not as fantastic as some stories, the Civil War experience of Callaway County is a remarkable microcosm in the story of a sharply divided border state. -

Historical Review

HISTORICAL REVIEW APRIL 1963 Fred Geary's "The Steamboat Idlewild' Published Quarterly By The State Historical Society of Missouri COLUMBIA, MISSOURI THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MISSOURI The State Historical Society of Missouri, heretofore organized under the laws of this State, shall be the trustee of this State—Laws of Missouri, 1899, R. S. of Mo., 1949, Chapter 183. OFFICERS 1962-65 ROY D. WILLIAMS, Boonville, President L. E. MEADOR, Springfield, First Vice President LEO J. ROZIER, Perryville, Second Vice President WILLIAM L. BRADSHAW, Columbia, Third Vice President RUSSELL V. DYE, Liberty, Fourth Vice President WILLIAM C TUCKER, Warrensburg, Fifth Vice President JOHN A. WINKLER, Hannibal, Sixth Vice President R. B. PRICE, Columbia, Treasurer FLOYD C SHOEMAKER, Columbia, Sacretary Emeritus and Consultant RICHARD S. BROWNLEE, Columbia, Director, Secretary, and Librarian TRUSTEES Permanent Trustees, Former Presidents of the Society E. L. DALE, Carthage E. E. SWAIN, Kirksville RUSH H. LIMBAUGH, Cape Girardeau L. M. WHITE, Mexico GEORGE A. ROZIER, Jefferson City Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1963 RALPH P. BIEBER, St. Louis LEO J. ROZIER, Perryville BARTLETT BODER, St. Joseph W. WALLACE SMITH, Independence L. E. MEADOR, Springfield JACK STAPLETON, Stanberry JOSEPH H. MOORE, Charleston HENRY C THOMPSON, Bonne Terre Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1964 WILLIAM R. DENSLOW, Trenton FRANK LUTHER MOTT, Columbia ALFRED O. FUERBRINGER, St. Louis GEORGE H. SCRUTON, Sedalia GEORGE FULLER GREEN, Kansas City JAMES TODD, Moberly ROBERT S. GREEN, Mexico T. BALLARD WATTERS, Marshfield Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1965 FRANK C BARNHILL, Marshall W. C HEWITT, Shelbyville FRANK P. BRIGGS, Macon ROBERT NAGEL JONES, St. -

Arkansas Moves Toward Secession and War

RICE UNIVERSITY WITH HESITANT RESOLVE: ARKANSAS MOVES TOWARD SECESSION AND WAR BY JAMES WOODS A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF ARTS Dr.. Frank E. Vandiver Houston, Texas ABSTRACT This work surveys the history of ante-bellum Arkansas until the passage of the Ordinance of Secession on May 6, 186i. The first three chapters deal with the social, economic, and politicai development of the state prior to 1860. Arkansas experienced difficult, yet substantial .social and economic growth during the ame-belium era; its percentage of population increase outstripped five other frontier states in similar stages of development. Its growth was nevertheless hampered by the unsettling presence of the Indian territory on its western border, which helped to prolong a lawless stage. An unreliable transportation system and a ruinous banking policy also stalled Arkansas's economic progress. On the political scene a family dynasty controlled state politics from 1830 to 186u, a'situation without parallel throughout the ante-bellum South. A major part of this work concentrates upon Arkansas's politics from 1859 to 1861. In a most important siate election in 1860, the dynasty met defeat through an open revolt from within its ranks led by a shrewd and ambitious Congressman, Thomas Hindman. Hindman turned the contest into a class conflict, portraying the dynasty's leadership as "aristocrats" and "Bourbons." Because of Hindman's support, Arkansans chose its first governor not hand¬ picked by the dynasty. By this election the people handed gubernatorial power to an ineffectual political novice during a time oi great sectional crisis. -

Battle of Lone Jack

Battle of Lone Jack The Battle of Lone Jack was a battle of the American next morning with the intent of overwhelming the much Civil War, occurring on August 15–August 16, 1862 in smaller Union force.[1] Jackson County, Missouri. The battle was part of the Confederate guerrilla and recruiting campaign in Mis- souri in 1862. 3 Battle 1 Background Cockrell’s plan was to clandestinely deploy Hunter, Jack- man and Tracy’s forces in a field to the west of town well before sunrise on August 16 and await the opening of the During the summer of 1862 many Confederate and fight. Hays was to initiate the battle with a mounted attack Missouri State Guard recruiters were dispatched north from the north as daylight approached, whereupon the from Arkansas into Missouri to replenish the de- others would launch a surprise flank attack.[2] Hays did pleted ranks of the Trans-Mississippi Confederacy. In not attack as early as planned, instead reconnoitering the Western/West-Central Missouri these included then Cap- other commands before advancing. As daylight appeared tain Jo Shelby, Colonel Vard Cockrell, Colonel John Foster’s pickets became aware of Hays’ advance. This T. Coffee, Upton Hays, John Charles Tracy, John T. gave Foster’s men a brief opportunity to deploy, spoiling Hughes, and DeWitt C. Hunter. Most of these commands the element of surprise.[3] were working independently and there was no clear sense of seniority yet established. On August 11 the Federal With sunrise exposing them while awaiting Hays’ tardy commander General John Schofield was stunned to learn advance, Jackman, Hunter, and Tracy attacked but were that Independence, Missouri had fallen to a combined held in check. -

Guide to a Microfilm Edition of the Alexander Ramsey Papers and Records

-~-----', Guide to a Microfilm Edition of The Alexander Ramsey Papers and Records Helen McCann White Minnesota Historical Society . St. Paul . 1974 -------~-~~~~----~! Copyright. 1974 @by the Minnesota Historical Society Library of Congress Catalog Number:74-10395 International Standard Book Number:O-87351-091-7 This pamphlet and the microfilm edition of the Alexander Ramsey Papers and Records which it describes were made possible by a grant of funds from the National Historical Publications Commission to the Minnesota Historical Society. Introduction THE PAPERS AND OFFICIAL RECORDS of Alexander Ramsey are the sixth collection to be microfilmed by the Minnesota Historical Society under a grant of funds from the National Historical Publications Commission. They document the career of a man who may be charac terized as a 19th-century urban pioneer par excellence. Ramsey arrived in May, 1849, at the raw settlement of St. Paul in Minne sota Territory to assume his duties as its first territorial gov ernor. The 33-year-old Pennsylvanian took to the frontier his family, his education, and his political experience and built a good life there. Before he went to Minnesota, Ramsey had attended college for a time, taught school, studied law, and practiced his profession off and on for ten years. His political skills had been acquired in the Pennsylvania legislature and in the U.S. Congress, where he developed a subtlety and sophistication in politics that he used to lead the development of his adopted city and state. Ram sey1s papers and records reveal him as a down-to-earth, no-non sense man, serving with dignity throughout his career in the U.S. -

Vol. 11 No. 4 – Fall 2017

Arkansas Military History Journal A Publication of the Arkansas National Guard Museum, Inc. Vol. 11 Fall 2017 No. 4 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Chairman Brigadier General John O. Payne Ex-Officio Vice Chairman Major General (Ret) Kendall Penn Ex-Officio Secretary Dr. Raymond D. Screws (Non-Voting) Ex-Officio Treasurer Colonel Damon N. Cluck Board Members Ex-Officio. Major Marden Hueter Ex-Officio. Captain Barry Owens At Large – Lieutenant Colonel (Ret) Clement J. Papineau, Jr. At Large – Chief Master Sergeant Melvin E. McElyea At Large – Major Sharetta Glover CPT William Shannon (Non-Voting Consultant) Lieutenant Colonel Matthew Anderson (Non-Voting Consultant) Deanna Holdcraft (Non-Voting Consultant) Museum Staff Dr. Raymond D. Screws, Director/Journal Editor Erica McGraw, Museum Assistant, Journal Layout & Design Incorporated 27 June 1989 Arkansas Non-profit Corporation Cover Photograph: The Hempstead Rifles, a volunteer militia company of the 8th Arkansas Militia Regiment,Hempstead County Table of Contents Message from the Editor ........................................................................................................ 4 The Arkansas Militia in the Civil War ...................................................................................... 5 By COL Damon Cluck The Impact of World War II on the State of Arkansas ............................................................ 25 Hannah McConnell Featured Artifact: 155 mm C, Model of 1917 Schneider ....................................................... 29 By LTC Matthew W. Anderson Message from the Editor The previous two issues of the journal focused on WWI and Camp Pike to coincide with the centennial of the United States entry into the First World War and the construction of the Post now known as Camp Pike. In the coming year, commemoration of the Great War will still be important, with the centennial of the Armistice on 11 November 2018. -

Battle and Event

Places and Major Events Reference Sheet (Map of Missouri with locations) 1. Wilson’s Creek- General Sterling Price of the Missouri State Guard and General McCulloch of the CSA defeated Federal troops under General Nathanial Lyon. General Lyon was killed during this engagement making him the highest ranking casualty of the war to that point. 2. New Madrid and Island No. 10 – From March 2 to April 8, 1862 Federal troops under General Ulysses S. Grant fought for control of Island No. 10 which had been controlled by Confederate forces for most of the war. This location allowed Confederates to impede Union invasion into the south. Brigadier General John P. McCown led the Confederate forces. The Union’s successful capture of the island was the first capture of a Confederate position on the Mississippi during the war. 3. Westport- Sometimes called the Gettysburg of the West the battle of Westport occurred in October of 1864 during General Sterling Price’s Missouri raid. This battle was the turning point in Price’s raid as superior Union forces under Major General Samuel R. Curtis forced Price’s army to retreat. This was the last major battle to be fought west of the Mississippi. 4. Cape Girardeau- On April 23, 1863 Union troops led by Brigadier General John McNeil faced Confederate Brigadier General John S. Marmaduke’s forces here. It was a relatively small engagement, but is significant because it was the running point in Marmaduke’s second raid into Missouri. 5. Camp Jackson- Brigadier General Nathanial Lyon led Federal troops to capture the state militia which had made camp here on May 10, 1861. -

With Fremont in Missouri in 1861

The Annals of Iowa Volume 24 Number 2 (Fall 1942) pps. 105-167 With Fremont in Missouri in 1861 ISSN 0003-4827 No known copyright restrictions. This work has been identified with a http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/NKC/1.0/">Rights Statement No Known Copyright. Recommended Citation "With Fremont in Missouri in 1861." The Annals of Iowa 24 (1942), 105-167. Available at: https://doi.org/10.17077/0003-4827.6181 Hosted by Iowa Research Online WITH FREMONT IN MISSOURI IN 1861 Letters of Samuel Ryan Curtis EDITED BY KENNETH E. COLTON This second installment of the letters of Samuel Ryan Curtis, Congressman, engineer, and soldier, continues the publication of his correspondence through the first year of the Civil War, begun in the July issue of The Annals of Iowa as "The Irrepressible Conflict of 1861." As this second series begins. Colonel S. R. Curtis is on his way east to Washington, to attend the special session of the Thirty-Seventh Congress, and hopeful of winning a general's star in the volunteer army of the United States. Meanwhile his troops, the 2nd Iowa Volun- teer Infantry, continues to guard the Hannibal & St. Joseph Railroad line, to which duty they had been ordered in June, one month before. The reader will be interested in Curtis' comment upon the problems of supply confronting the Federal forces in 1861, problems much in the public mind in 1942, facing another war. Of special interest in this series of the war correspondence are the accounts of the developing crisis in the military command of the Department of the West, under that eccentric, colorful and at times pathetic figure. -

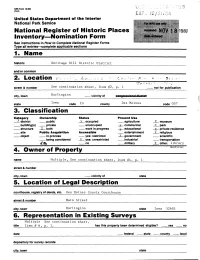

3. Classification 4. Owner of Property

NPS Form 10-900 (7-81) LASP VC United States Department off the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name historic Heritage Hill Historic District and/or common 2. Location f) £ I. i \ -. fT, •-,• (J C e v", l r •- V a street & number See continuation sheet, Item #2, p. 1 not for publication city, town Burlington vicinity of Iowa state code 19 county Des Moines code 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use X district public X occupied agriculture X museum building(s) private unoccupied X commercial X park structure X both work in progress X educational X private residence Site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment X religious object in process yes: restricted X government scientific being considered x yes: unrestricted industrial transportation K\*s __ no military _JL_ other: library 4. Owner of Property medical name Multiple, See continuation sheet, Item #4, p* 1 street & number city, town vicinity of state 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Des Moines County Courthouse street & number Main Street city, town Burlington state Iowa 52601 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Multiple See continuation sheet, title Item #6, p. 1. has this property been determined eligible? yes no date federal state county local depository for survey records city, town state 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated unaltered xx original site XX good ruins XX altered moved date fair unevnosed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance A first view of the Heritage Hill Historic District gives the impression of a Victorian neighborhood with an unusually large number of impressive church structures. -

November 2010 General Orders Vol. 22 No. 4

Vol. 22 General Orders No. 4 Nov. Rains’ Regiment 2010 www.houstoncivilwar.com NOVEMBER 2010 MEETING Background on Thursday, November 18, 2010 The Battle of Pea Ridge The Briar Club 2603 Timmons Lane @ Westheimer From the Jaws of Victory: The Confederate 6:00 Cash Bar Defeat at the Battle of Pea Ridge will explore the Pea 7:00 Dinner & Meeting Ridge campaign from the perspective of the Confederate Army of the West. The Army of the West E-Mail Reservation is Preferred; was one of the largest Confederate armies raised at [email protected] west of the Mississippi River yet during the battle of or call Don Zuckero at (281) 479-1232 Pea Ridge a series of blunders and unfortunate by 6 PM on Monday Nov. 15, 2010 events would ultimately lead to their defeat by the Dinner $33; Lecture Only $5 smaller Union Army of the Southwest. The Confederate loss helped secure the state of Missouri Reservations are required for Lecture Only! for the Union and freed up several thousand Union troops that could be utilized for other campaigns. By late 1861 and early 1862, Federal forces in The HCWRT PRESENTS Missouri had pushed nearly all Confederate forces out of the state. When General Earl Van Dorn took Troy Banzhaf and command of the department, he had to react with his roughly 17,000 man, 60 gun Army of the West to “The Battle of Pea Ridge” events already underway. Van Dorn wanted to attack and destroy the Union forces, make his way into For our November 2010 meeting, the Houston Missouri, and capture St.