Evil Dead II . . . Meet Thy Doom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

III. Here Be Dragons: the (Pre)History of the Adventure Game

III. Here Be Dragons: the (pre)history of the adventure game The past is like a broken mirror, as you piece it together you cut yourself. Your image keeps shifting and you change with it. MAX PAYNE 2: THE FALL OF MAX PAYNE At the end of the Middle Ages, Europe’s thousand year sleep – or perhaps thousand year germination – between antiquity and the Renaissance, wondrous things were happening. High culture, long dormant, began to stir again. The spirit of adventure grew once more in the human breast. Great cathedrals rose, the spirit captured in stone, embodiments of the human quest for understanding. But there were other cathedrals, cathedrals of the mind, that also embodied that quest for the unknown. They were maps, like the fantastic, and often fanciful, Mappa Mundi – the map of everything, of the known world, whose edges both beckoned us towards the unknown, and cautioned us with their marginalia – “Here be dragons.” (Bradbury & Seymour, 1997, p. 1357)1 At the start of the twenty-first century, the exploration of our own planet has been more or less completed2. When we want to experience the thrill, enchantment and dangers of past voyages of discovery we now have to rely on books, films and theme parks. Or we play a game on our computer, preferably an adventure game, as the experience these games create is very close to what the original adventurers must have felt. In games of this genre, especially the older type adventure games, the gamer also enters an unknown labyrinthine space which she has to map step by step, unaware of the dragons that might be lurking in its dark recesses. -

2K and Bethesda Softworks Release Legendary Bundles February 11

2K and Bethesda Softworks Release Legendary Bundles February 11, 2014 8:00 AM ET The Elder Scrolls® V: Skyrim and BioShock® Infinite; Borderlands® 2 and Dishonored™ bundles deliver supreme quality at an unprecedented price NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Feb. 11, 2014-- 2K and Bethesda Softworks® today announced that four of the most critically-acclaimed video games of their generation – The Elder Scrolls® V: Skyrim, BioShock® Infinite, Borderlands® 2, and Dishonored™ – are now available in two all-new bundles* for $29.99 each in North America on the Xbox 360 games and entertainment system from Microsoft, PlayStation®3 computer entertainment system, and Windows PC. ● The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim & BioShock Infinite Bundle combines two blockbusters from world-renowned developers Bethesda Game Studios and Irrational Games. ● The Borderlands 2 & Dishonored Bundle combines Gearbox Software’s fan favorite shooter-looter with Arkane Studio’s first- person action breakout hit. Critics agree that Skyrim, BioShock Infinite, Borderlands 2, and Dishonored are four of the most celebrated and influential games of all time. 2K and Bethesda Softworks(R) today announced that four of the most critically- ● Skyrim garnered more than 50 perfect review acclaimed video games of their generation - The Elder Scrolls(R) V: Skyrim, scores and more than 200 awards on its way BioShock(R) Infinite, Borderlands(R) 2, and Dishonored(TM) - are now available to a 94 overall rating**, earning praise from in two all-new bundles* for $29.99 each in North America on the Xbox 360 some of the industry’s most influential and games and entertainment system from Microsoft, PlayStation(R)3 computer respected critics. -

Models of Time Travel

MODELS OF TIME TRAVEL A COMPARATIVE STUDY USING FILMS Guy Roland Micklethwait A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University July 2012 National Centre for the Public Awareness of Science ANU College of Physical and Mathematical Sciences APPENDIX I: FILMS REVIEWED Each of the following film reviews has been reduced to two pages. The first page of each of each review is objective; it includes factual information about the film and a synopsis not of the plot, but of how temporal phenomena were treated in the plot. The second page of the review is subjective; it includes the genre where I placed the film, my general comments and then a brief discussion about which model of time I felt was being used and why. It finishes with a diagrammatic representation of the timeline used in the film. Note that if a film has only one diagram, it is because the different journeys are using the same model of time in the same way. Sometimes several journeys are made. The present moment on any timeline is always taken at the start point of the first time travel journey, which is placed at the origin of the graph. The blue lines with arrows show where the time traveller’s trip began and ended. They can also be used to show how information is transmitted from one point on the timeline to another. When choosing a model of time for a particular film, I am not looking at what happened in the plot, but rather the type of timeline used in the film to describe the possible outcomes, as opposed to what happened. -

Xavier Aldana Reyes, 'The Cultural Capital of the Gothic Horror

1 Originally published in/as: Xavier Aldana Reyes, ‘The Cultural Capital of the Gothic Horror Adaptation: The Case of Dario Argento’s The Phantom of the Opera and Dracula 3D’, Journal of Italian Cinema and Media Studies, 5.2 (2017), 229–44. DOI link: 10.1386/jicms.5.2.229_1 Title: ‘The Cultural Capital of the Gothic Horror Adaptation: The Case of Dario Argento’s The Phantom of the Opera and Dracula 3D’ Author: Xavier Aldana Reyes Affiliation: Manchester Metropolitan University Abstract: Dario Argento is the best-known living Italian horror director, but despite this his career is perceived to be at an all-time low. I propose that the nadir of Argento’s filmography coincides, in part, with his embrace of the gothic adaptation and that at least two of his late films, The Phantom of the Opera (1998) and Dracula 3D (2012), are born out of the tensions between his desire to achieve auteur status by choosing respectable and literary sources as his primary material and the bloody and excessive nature of the product that he has come to be known for. My contention is that to understand the role that these films play within the director’s oeuvre, as well as their negative reception among critics, it is crucial to consider how they negotiate the dichotomy between the positive critical discourse currently surrounding gothic cinema and the negative one applied to visceral horror. Keywords: Dario Argento, Gothic, adaptation, horror, cultural capital, auteurism, Dracula, Phantom of the Opera Dario Argento is, arguably, the best-known living Italian horror director. -

Klassiker Der Spielegeschichte

Klassiker der Spielegeschichte Tex murphy: tesla effect 17. Januar 2015 Prof. Dr. Jochen Koubek | Universität Bayreuth | Digitale Medien | [email protected] Tex Murphy Mean Streets (1989) Martian Memorandum (1992) Under a Killing Moon (1994) The Pandora Directive (1996) Tex Murphy: Overseer (1998) Access Games / Indie Built / Big Finish Games • 1982 Gründung von Acces Games • 1999 Kauf durch Microsoft, Umbenennung in Salt Lake Game Studio • 2003 Umbenennung in Indie Games • 2004 Kauf durch Take-Two Interactive, Umbennenung in Indie Built • 2006 Auflösung • 2007 Neugründung als Big Finish Games Christopher Jones http://www.mobygames.com/developer/sheet/view/developerId,1089/ Writer Game Design Production Video / Cinematics Quality Assurance Creative Service 2000! 2011! Love Story Asuras Wrath Star Strike Conspiracies II – Lethal Networks The Exterminators I Am Playr 2001 Jurassic Park: The Game Point of View Take This Lollipop 2003 2012! Conspiracies The Oogieloves in the Big Balloon Adventure 2004 The Silver Nugget The Guy Game The Walking Dead 2005 2013! Doctor Who: Attack of the Graske Bear Stearns Bravo Fahrenheit Beyond: Two Souls School Days Hero of Shaolin 2006! The Walking Dead: Season Two Railfan: Chicago Transit Authority Brown Line The Wolf Among Us Yoomurjak's Ring original Hungarian release 2014! 2007! A Bird Story Railfan: Taiwan High Speed Rail Tesla Effect: A Tex Murphy Adventure The Act Tales from the Borderlands 2008! Game of Thrones Casebook Contradiction Mystery Case Files: Dire Grove Cloud Chamber 2010! Darkstar: -

Activision Ships Over Two Million Units of Spider-Man 2TM Video Game

Activision Ships Over Two Million Units Of Spider-Man 2TM Video Game Santa Monica, CA - July 7, 2004 - Activision, Inc. (Nasdaq: ATVI) announced today that the company's North American Publishing unit has shipped more than two million units of its Spider-Man 2™ video game timed to the theatrical release of Sony Pictures Entertainment's Columbia Pictures Spider-Man® 2. The game, which is currently available at retail stores, lets players experience what it's like to be the world's most celebrated Super Hero as they web sling from buildings, dive from rooftops to the streets and scale the heights of Manhattan, a living breathing city complete with pedestrians, traffic, trains and helicopters. Gamers can re-live the film's storyline or embark on exclusive game missions as they perform heroic deeds, protect citizens from random crimes, and face off against the nefarious Doc Ock and other Marvel super-villains. Spider-Man 2 for the PlayStation®2 computer entertainment system, the Xbox® video game system from Microsoft and Nintendo GameCube™ carry a "T" (Teen with violence) rating by the ESRB and the Game Boy® Advance and PC versions carry an "E" (Everyone with violence) rating. In Columbia Pictures' Spider-Man 2, two years have passed since Peter Parker (Tobey Maguire) walked away from his longtime love Mary Jane Watson (Kirsten Dunst) and decided to take the road to responsibility as Spider-Man. Peter must face new challenges as he struggles to cope with "the gift and the curse" of his powers while balancing his dual identities as the elusive superhero Spider-Man and life as a college student. -

Dp Guide Lite Us

Dreamcast USA Digital Press GB I GB I GB I 102 Dalmatians: Puppies to the Re R1 Dinosaur (Disney's)/Ubi Soft R4 Kao The Kangaroo/Titus R4 18 Wheeler: American Pro Trucker R1 Donald Duck Goin' Quackers (Disn R2 King of Fighters Dream Match, The R3 4 Wheel Thunder/Midway R2 Draconus: Cult of the Wyrm/Crave R2 King of Fighters Evolution, The/Ag R3 4x4 Evolution/GOD R2 Dragon Riders: Chronicles of Pern/ R4 KISS Psycho Circus: The Nightmar R1 AeroWings/Crave R4 Dreamcast Generator Vol. 01/Sega R0 Last Blade 2, The: Heart of the Sa R3 AeroWings 2: Airstrike/Crave R4 Dreamcast Generator Vol. 02/Sega R0 Looney Toons Space Race/Infogra R2 Air Force Delta/Konami R2 Ducati World Racing Challenge/Acc R4 MagForce Racing/Crave R2 Alien Front Online/Sega R2 Dynamite Cop/Sega R1 Magical Racing Tour (Walt Disney R2 Alone In The Dark: The New Night R2 Ecco the Dolphin: Defender of the R2 Maken X/Sega R1 Armada/Metro3D R2 ECW Anarchy Rulez!/Acclaim R2 Mars Matrix/Capcom R3 Army Men: Sarge's Heroes/Midway R2 ECW Hardcore Revolution/Acclaim R1 Marvel vs. Capcom/Capcom R2 Atari Anniversary Edition/Infogram R2 Elemental Gimmick Gear/Vatical R1 Marvel vs. Capcom 2: New Age Of R2 Bang! Gunship Elite/RedStorm R3 ESPN International Track and Field R3 Mat Hoffman's Pro BMX/Activision R4 Bangai-o/Crave R4 ESPN NBA 2 Night/Konami R2 Max Steel/Mattel Interact R2 bleemcast! Gran Turismo 2/bleem R3 Evil Dead: Hail to the King/T*HQ R3 Maximum Pool (Sierra Sports)/Sier R2 bleemcast! Metal Gear Solid/bleem R2 Evolution 2: Far -

Loot Crate and Bethesda Softworks Announce Fallout® 4 Limited Edition Crate Exclusive Game-Related Collectibles Will Be Available November 2015

Loot Crate and Bethesda Softworks Announce Fallout® 4 Limited Edition Crate Exclusive Game-Related Collectibles Will Be Available November 2015 LOS ANGELES, CA -- (July 28th, 2015) -- Loot Crate, the monthly geek and gamer subscription service, today announced their partnership today with Bethesda Softworks® to create an exclusive, limited edition Fallout® 4 crate to be released in conjunction with the game’s worldwide launch on November 10, 2015 for the Xbox One, PlayStation® 4 computer entertainment system and PC. Bethesda Softworks exploded hearts everywhere when they officially announced Fallout 4 - the next generation of open-world gaming from the team at Bethesda Game Studios®. Following the game’s official announcement and its world premiere during Bethesda’s E3 Showcase, Bethesda Softworks and Loot Crate are teaming up to curate an official specialty crate full of Fallout goods. “We’re having a lot of fun working with Loot Crate on items for this limited edition crate,” said Pete Hines, VP of Marketing and PR at Bethesda Softworks. “The Fallout universe allows for so many possibilities – and we’re sure fans will be excited about what’s in store.” "We're honored to partner with the much-respected Bethesda and, together, determine what crate items would do justice to both Fallout and its fans," says Matthew Arevalo, co-founder and CXO of Loot Crate. "I'm excited that I can FINALLY tell people about this project, and I can't wait to see how the community reacts!" As is typical for a Loot Crate offering, the contents of the Fallout 4 limited edition crate will remain a mystery until they are delivered in November. -

High-Performance Play: the Making of Machinima

High-Performance Play: The Making of Machinima Henry Lowood Stanford University <DRAFT. Do not cite or distribute. To appear in: Videogames and Art: Intersections and Interactions, Andy Clarke and Grethe Mitchell (eds.), Intellect Books (UK), 2005. Please contact author, [email protected], for permission.> Abstract: Machinima is the making of animated movies in real time through the use of computer game technology. The projects that launched machinima embedded gameplay in practices of performance, spectatorship, subversion, modification, and community. This article is concerned primarily with the earliest machinima projects. In this phase, DOOM and especially Quake movie makers created practices of game performance and high-performance technology that yielded a new medium for linear storytelling and artistic expression. My aim is not to answer the question, “are games art?”, but to suggest that game-based performance practices will influence work in artistic and narrative media. Biography: Henry Lowood is Curator for History of Science & Technology Collections at Stanford University and co-Principal Investigator for the How They Got Game Project in the Stanford Humanities Laboratory. A historian of science and technology, he teaches Stanford’s annual course on the history of computer game design. With the collaboration of the Internet Archive and the Academy of Machinima Arts and Sciences, he is currently working on a project to develop The Machinima Archive, a permanent repository to document the history of Machinima moviemaking. A body of research on the social and cultural impacts of interactive entertainment is gradually replacing the dismissal of computer games and videogames as mindless amusement for young boys. There are many good reasons for taking computer games1 seriously. -

Visual Design in Video Games

Forthcoming in WOLF, Mark J.P. (ed.). Video Game History: From Bouncing Blocks to a Global Industry, Greenwood Press, Westport, Conn. Visual Design in Video Games Carl Therrien So why did polygons become the ubiquitous virtual bricks of videogames? Because, whatever the interesting or eccentric devices that had been thrown up along the way, videogames, as with the strain of Western art from the Renaissance up until the shock of photography, were hell-bent on refining their powers of illusionistic deception. —Stephen Poole (2000, page 125). Illusion refining, indeed, appears to be a major driving force of video game evolution. The appeal of ever-more realistic depictions of virtual universes in itself justifies the purchase of expensive new machinery, be it the latest console or dedicated computer parts. Yet, one must not conceive of this evolution as a linear progression towards perfect verisimilitude. The relative quality of static and dynamic renders, associated with a wide range of imaging techniques more or less suited to the capabilities of any given video game system, demonstrate the unsteady evolution of visual representation in the short history of the medium. Moreover, older techniques are sometimes integrated in the latest 3-D games, and 2-D gaming still enjoys a very strong following with portable game systems. Despite its short history, a detailed account of the apparatus behind the illusion would already require many volumes in itself. In this chapter, we will examine only the fundamentals of the different imaging techniques along with key examples. However, we hope to go further than a simple historical account of illusion refining, and expose the different ideals that governed and still governs the evolution of visual design in games. -

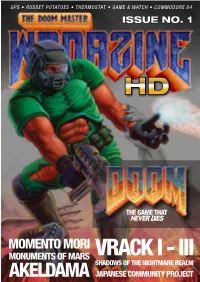

THE GAME THAT NEVER DIES Index

GPS • RUSSET POTATOES • THERMOSTAT • GAME & WATCH • COMMODORE 64 THE GAME THAT NEVER DIES IndeX Doom Re-Master Wadazine Introduction ........................................................... 4 Doom, the Game that Never Dies ....................................................................... 5 Master Recommendation 1: Akeldama .............................................................. 8 WAD Corner: Memento Mori ................................................................................................ 10 Japanese Community Project ........................................................................ 11 Vrack 1, 2, and 3 ............................................................................................ 12 Monuments of Mars ....................................................................................... 13 Shadows of the Nightmare Realm ................................................................ 14 NewStuff on Doomworld ................................................................................... 15 Pictures Gallery ................................................................................................. 16 WRITERS OF THIS FIRST ISSUE: Endless VERY SPECIAL THANKS TO: Doomkid, Chris Hansen, and Ryath, our hosts. Bridgerburner56, Major Arlene, Gaia74 and Taufan99, server mods and advisers. 4MaTC and Nikoxenos, our Wadazine editors & wizards. Elend, designer of every single Wadazine logo and related. Clueless, my best friend and extremely supportive for everything. ‹rd›, for giving me some -

Christy Marx

Write Your Way Into Animation and Games Write Your Way Into Animation and Games Create a Writing Career in Animation and Games Christy Marx AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HEIDELBERG • LONDON NEW YORK • OXFORD • PARIS • SAN DIEGO SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPORE • SYDNEY • TOKYO Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier 30 Corporate Drive, Suite 400, Burlington, MA 01803, USA Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford OX2 8DP, UK © 2010 Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, elec- tronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Details on how to seek permission, fur- ther information about the Publisher’s permissions policies and our arrangements with organiza- tions such as the Copyright Clearance Center and the Copyright Licensing Agency, can be found at our website: www.elsevier.com/permissions. This book and the individual contributions contained in it are protected under copyright by the Publisher (other than as may be noted herein). Notices Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treat- ment may become necessary. Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluat- ing and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility.