F 0 Undati 0

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Becoming Lutheran: Exploring the Journey of American Evangelicals Into Confessional Lutheran Thought

Concordia Seminary - Saint Louis Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary Doctor of Ministry Major Applied Project Concordia Seminary Scholarship 9-23-2013 Becoming Lutheran: Exploring the Journey of American Evangelicals into Confessional Lutheran Thought Matthew Richard Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.csl.edu/dmin Part of the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Richard, Matthew, "Becoming Lutheran: Exploring the Journey of American Evangelicals into Confessional Lutheran Thought" (2013). Doctor of Ministry Major Applied Project. 138. https://scholar.csl.edu/dmin/138 This Major Applied Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Concordia Seminary Scholarship at Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctor of Ministry Major Applied Project by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONCORDIA SEMINARY SAINT LOUIS, MISSOURI BECOMING LUTHERAN: EXPLORING THE JOURNEY OF AMERICAN EVANGELICALS INTO CONFESSIONAL LUTHERAN THOUGHT A MAJOR APPLIED PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF DOCTOR OF MINISTRY STUDIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MINISTRY BY REV. MATTHEW R. RICHARD SAINT LOUIS, MISSOURI BECOMING LUTHERAN: EXPLORING THE JOURNEY OF AMERICAN EVANGELICALS INTO CONFESSIONAL LUTHERAN THOUGHT REV. MATTHEW R. RICHARD SEPTEMBER 23, 2013 Concordia Seminary Saint Louis, Missouri Advisor DR. ROBERT -

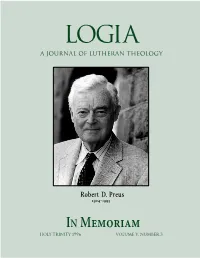

Robert D. Preus ‒

Logia a journal of lutheran theology Robert D. Preus ‒ IN M Holy Trinity 1996 volume v, number 3 ei[ ti" lalei', FREQUENTLY USED ABBREVIATIONS wJ" lovgia Qeou' AC [CA] Augsburg Confession AE Luther’s Works, American Edition logia is a journal of Lutheran theology. As such it publishes Ap Apology of the Augsburg Confession articles on exegetical, historical, systematic, and liturgical theol- BSLK Die Bekenntnisschriften der evangelisch-lutherischen Kirche ogy that promote the orthodox theology of the Evangelical Ep Epitome of the Formula of Concord Lutheran Church. We cling to God’s divinely instituted marks of FC Formula of Concord the church: the gospel, preached purely in all its articles, and the LC Large Catechism sacraments, administered according to Christ’s institution. This LW Lutheran Worship name expresses what this journal wants to be. In Greek, LOGIA SA Smalcald Articles functions either as an adjective meaning “eloquent,” “learned,” SBH Service Book and Hymnal or “cultured,” or as a plural noun meaning “divine revelations,” “words,” or “messages.” The word is found in Peter :, Acts SC Small Catechism :, and Romans :. Its compound forms include oJmologiva SD Solid Declaration of the Formula of Concord (confession), ajpologiva (defense), and ajvnalogiva (right relation- Tappert The Book of Concord: The Confessions of the Evangelical ship). Each of these concepts and all of them together express the Lutheran Church. Trans. and ed. Theodore G. Tappert TDNT Theological Dictionary of the New Testament purpose and method of this journal. LOGIA considers itself a free conference in print and is committed to providing an indepen- TLH The Lutheran Hymnal dent theological forum normed by the prophetic and apostolic Tr Treatise on the Power and Primacy of the Pope Scriptures and the Lutheran Confessions. -

Church History Time Line (Mainly Latin – Pre/Post Schism)

Church History Time Line (mainly Latin – pre/post Schism) Middle Ages 800 King Charlemagne of the Franks is crowned first Holy Roman Emperor of the West by Pope Leo III. 849-865 Ansgar, Archbishop of Bremen, "Apostle of the North", began evangelisation of North Germany, Denmark, Sweden 855 Antipope Anastasius, Louis II, Holy Roman Emperor appointed him over Pope Benedict III but popular pressure caused withdrawal 863 Saint Cyril and Saint Methodius sent by the Patriarch of Constantinople to evangelise the Slavic peoples. They translate the Bible into Slavonic. 869-870 Catholic Fourth Council of Constantinople, condemned Patriarch Photius, rejected by Orthodox 879-880 Orthodox Fourth Council of Constantinople, restored Photius, condemned Pope Nicholas I and Filioque, rejected by Catholics 897,January Cadaver Synod, Pope Stephen VI conducts trial against dead Pope Formosus, public uprising against Stephen led to his imprisonment and strangulation 909 Abbey of Cluny, Benedictine monastery in France 948? Einsiedeln Abbey of Switzerland 966 Mieszko I duke of Poland baptised, Poland becomes a Christian country. 984 Antipope Boniface VII, murdered Pope John XIV, alleged to have murdered Pope Benedict VI in 974 988 Baptism of Kievan Rus' 997-998 Antipope John XVI, deposed by Pope Gregory V and his cousin Holy Roman Emperor Otto III 999 Much speculation and fear regarding the approach of the millennium 1001 Byzantine emperor Basil II and Fatimid Caliph Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah execute a treaty guaranteeing the protection of Christian pilgrimage routes in the Middle East 1004-1014 Caliph Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah turned violently against his Christian mother and uncles (two of whom were Patriarchs).