The Tensions That Make Truth for India's Ahmadi Muslims Nicholas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jalsa Salana UK 2016

UK JALSA SALANA 2016 PART 4 A Personal Account By Abid Khan 1 Introduction to Part 4 This is the concluding part of the personal account I have written in relation to Huzoor’s activities during the days of Jalsa Salana 2016, as well as the week preceding it and the week after. This final part will include further meetings held by Huzoor with various groups, as well as media interviews and various other activities. Tunisia delegation On Wednesday 17 August 2016, Huzoor’s meetings with delegations of Ahmadis and non-Ahmadi guests from different countries continued. One group to meet Huzoor that morning was a delegation from Tunisia. At the very start of the meeting, the Tunisian delegation placed a fruit tree on Huzoor’s desk as a gift. Upon accepting the gift, Huzoor said: “Is your Jamaat also giving me the fruit of increasing numbers of pious Ahmadis?” In reply, the Tunisian group replied all together saying: “Insha’Allah” 2 Huzoor then said: “In our Jamaat we should seek the best fruits which are of piety and spirituality.” Thereafter, an Arab Ahmadi, who was attending the UK Jalsa for the very first time, became very emotional. He informed Huzoor that he had recently seen a dream in which he saw the Promised Messiah (as), who handed the Ahmadi a copy of his book Brahin- e-Ahmadiyya printed on green paper. He was then handed another book by the Fourth Khalifa (rh), which was about Islam, and printed on white paper. Thereafter, the Promised Messiah (as) told the Ahmadi to give these books to the Arabs. -

Odyssey-Of-Sacrifice.Pdf

Odyssey of Sacrifice A Compilation of Anecdotes on Financial Sacrifice by Anwer Mahmood Khan 2015! Published by Majlis Khuddamul Ahmadiyya USA Cover design by Salman Sajid ! 1 Odyssey of Sacrifice Published August 2015 By Majlis Khuddamul-Ahmadiyya USA at Fazl-i-Umar Press PO BOX 226 Chauncey, OH 45719 United States of America ©2015 Majlis Khuddamul-Ahmadiyya USA ! 2 Table of Contents A letter from Hazrat Khalifatul Masih V (aba) ...................................................... 7 Foreword ..................................................................................................................... 9 Author’s Note ........................................................................................................... 11 A message from Sadr MKA USA ............................................................................. 13 A message from MKA USA Tehrik-e-Jadid Department .................................... 15 Abbreviations ........................................................................................................... 16 Concept of Sacrifice ................................................................................................. 17 Exemplary Sacrifices of the Holy Prophet Muhammad (sa) ............................. 19 Sacrifices of Sahaba (ra) ......................................................................................... 22 Sacrifices of Imam Mahdi (as) ................................................................................ 27 Sacrifices of Sahaba (ra) of Hazrat Ahmad (as) .................................................. -

HUZOOR's TOUR of GERMANY JUNE 2014 a Personal Account By

HUZOOR’S TOUR OF GERMANY JUNE 2014 A Personal Account PART 2 By Abid Khan 1 Departure for Munich On 9th June 2014, Huzoor and his Qafila departed from the Baitus Sabuh Mosque in Frankfurt at 10.15am. We were travelling to Neufahrn a small town, known as a municipality, lying in the suburbs of Germany’s famous city of Munich. Huzoor was travelling to inaugurate the Al-Mahdi Mosque. Apart from Berlin, Munich is considered to be Germany’s most famous city internationally. It is home to the famous football team ‘Bayern Munich’ and also home to the renowned car maker BMW. The drive from Frankfurt took nearly 3 and a half hours and as we approached Neufahrn the Qafila cars were escorted by 2 police cars. One of the police cars was a ‘special forces’ car which travelled at the rear of the Qafila, whilst the other police car acted as the lead car. Apart from these 2 cars there were other police cars that had completely blocked traffic on certain roads so that Huzoor’s car could travel directly without any delay. As I saw this I felt a great deal of gratitude to the German authorities for welcoming Huzoor in such a positive way. 2 Arrival in Munich We arrived at the AlMahdi Mosque at 1.35pm where Huzoor was greeted by a local dignitary. The dignitary spoke very passionately as he welcomed Huzoor and said that he held a very deep respect for the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community. Huzoor thanked him for his courtesy and kindness. -

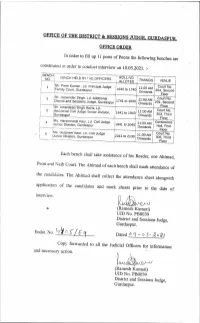

Roll Number.Pdf

POST APPLIED FOR :- PEON Roll No. Application No. Name Father’s Name/ Husband’s Name Permanent Address 1 284 Aakash Subash Chander Hno 241/2 Mohalla Nangal Kotli Mandi Gurdaspur 2 792 Aakash Gill Tarsem lal Village Abulkhair Jail Road, Gurdaspur 3 1171 Aakash Masih Joginder Masih Village Chuggewal 4 1014 Aakashdeep Wazir Masih Village Tariza Nagar, PO Dhariwal, Gurdaspur 5 2703 Abhay Saini Parvesh Saini house no DF/350,4 Marla Quarter Ram Nagar Pathankot 6 1739 Abhi Bhavnesh Kumar Ward No. 3, Hno. 282, Kothe Bhim Sen, Dinanagar 7 1307 Abhi Nandan Niranjan Singh VPO Bhavnour, tehsil Mukerian , District Hoshiarpur 8 1722 Abhinandan Mahajan Bhavnesh Mahajan Ward No. 3, Hno. 282, Kothe Bhim Sen, Dinanagar 9 305 Abhishek Danial Hno 145, ward No. 12, Line No. 18A Mill QTR Dhariwal, District Gurdaspur 10 465 Abhishek Rakesh Kumar Hno 1479, Gali No 7, Jagdambe Colony, Majitha Road , Amritsar 11 1441 Abhishek Buta Masih Village Triza Nagar, PO Dhariwal, Gurdaspur 12 2195 Abhishek Vijay Kumar Village Meghian, PO Purana Shalla, Gurdaspur 13 2628 Abhishek Kuldeep Ram VPO Rurkee Tehsil Phillaur District Jalandhar 14 2756 Abhishek Shiv Kumar H.No.29B, Nehru Nagar, Dhaki road, Ward No.26 Pathankot-145001 15 1387 Abhishek Chand Ramesh Chand VPO Sarwali, Tehsil Batala, District Gurdaspur 16 983 Abhishek Dadwal Avresh Singh Village Manwal, PO Tehsil and District Pathankot Page 1 POST APPLIED FOR :- PEON Roll No. Application No. Name Father’s Name/ Husband’s Name Permanent Address 17 603 Abhishek Gautam Kewal Singh VPO Naurangpur, Tehsil Mukerian District Hoshiar pur 18 1805 Abhishek Kumar Ashwani Kumar VPO Kalichpur, Gurdaspur 19 2160 Abhishek Kumar Ravi Kumar VPO Bhatoya, Tehsil and District Gurdaspur 20 1363 Abhishek Rana Satpal Rana Village Kondi, Pauri Garhwal, Uttra Khand. -

Download Book

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES THE RELIGIOUS LIFE OF INDIA EDITED BY J. N. FARQUHAR, M.A., D.Litt. LITERARY SECRETARY, NATIONAL COUNCIL, YOUNG MEN'S CHRISTIAN ASSOCIATIONS, INDIA AND CEYLON ; AND NICOL MACNICOL, M.A., D.Litt. ALREADY PUBLISHED THE VILLAGE GODS OF SOUTH INDIA. By the Bishop OF Madras. VOLUMES UNDER PREPARATION THE VAISHNAVISM OF PANDHARPUR. By NicoL Macnicol, M.A., D.Litt., Poona. THE CHAITANYAS. By M. T. Kennedy, M.A., Calcutta. THE SRI-VAISHNAVAS. By E. C. Worman, M.A., Madras. THE SAIVA SIDDHANTA. By G. E. Phillips, M.A., and Francis Kingsbury, Bangalore. THE VIRA SAIVAS. By the Rev. W. E. Tomlinson, Gubbi, Mysore. THE BRAHMA MOVEMENT. By Manilal C. Parekh, B.A., Rajkot, Kathiawar. THE RAMAKRISHNA MOVEMENT. By I. N. C. Ganguly, B.A., Calcutta. THE StJFlS. By R. Siraj-ud-Din, B.A., and H. A. Walter, M.A., Lahore. THE KHOJAS. By W. M. Hume, B.A., Lahore. THE MALAS and MADIGAS. By the Bishop of Dornakal and P. B. Emmett, B.A., Kurnool. THE CHAMARS. By G. W. Briggs, B.A., Allahabad. THE DHEDS. By Mrs. Sinclair Stevenson, M.A., D.Sc, Rajkot, Kathiawar. THE MAHARS. By A. Robertson, M.A., Poona. THE BHILS. By D. Lewis, Jhalod, Panch Mahals. THE CRIMINAL TRIBES. By O. H. B. Starte, I.C.S., Bijapur. EDITORIAL PREFACE The purpose of this series of small volumes on the leading forms which religious life has taken in India is to produce really reliable information for the use of all who are seeking the welfare of India, Editor and writers alike desire to work in the spirit of the best modern science, looking only for the truth. -

Orthopedically Handicapped (OH) Category 1 81 Raj Kumar S/O Ashok 70, Isa Nagasr , Batala, 10.09.1983 OH 20% Kumar Distt

Department of Local Government Punjab (Punjab Municipal Bhawan, Plot No.-3, Sector-35 A, Chandigarh) Detail of application for the posts of Safai Karamchari (Service Group-D) reserved for Disabled Persons in the cadre of Municipal Corporations and Municipal Councils-Nagar Panchayats in Punjab Sr. App Name of Candidate Address Date of Birth VH, HH, OH No. No. and Father’s Name etc. %age of Sarv Shri/ Smt./Miss Disability 1 2 3 4 5 6 Orthopedically Handicapped (OH) Category 1 81 Raj Kumar S/o Ashok 70, Isa Nagasr , Batala, 10.09.1983 OH 20% Kumar Distt. Gurdaspur (143505) Disability less then 40% 2 94 Manjeet Kaur D/o Vill. Mann, Teh. & Distt. 26.03.1999 OH 75% Pritam Singh Gurdaspur 3 103 Sukhbir Kaur D/o Vill. Ratta, Teh.- Dera 17.03.1998 OH 50% Sukhdev Singh Baba Nanak, Distt.- Gurdaspur 4 111 Rajesh Kumar S/o New Colony, ITI 12.02.1978 OH 74 % Baldev Raj Gurdaspur, Teh & Distt.- Gurdaspur 5 147 Ranjeet Singh S/o Dalla Kalan, P.O. Kadian, 05.02.1966 OH 40% Darshan Singh Distt- Gurdaspur, 143516 6 224 Rajinder Kumar S/o VPO Khojepur, Distt.& 18.03.1980 OH 55% Anchal Dass Teh. Gurdaspur. 7 279 Anil Kumar S/o Om VPO- Marara, Teh. & 09.07.1992 OH 60% Parkash Distt. Gurdaspur-143525. 8 331 Kuldeep Sharma S/o Vill. Dabur, P.O Magar 01.08.1988 OH 60% Darshan Kumar Mudia, Gurdaspur 9 335 Amandeep Singh S/o Vill. Raowal, P.O Deena 12.07.1992 OH 51% Karnail Singh Nagar, Teh. -

Repair Programme 2018-19 Administr Ative Detail of Repair Sr

Repair Programme 2018-19 Administr ative Detail of Repair Sr. Approval Name of Name Xen/Mobile No. Distt. MC Name of Work No. Strengthe Premix Contractor/Agency Name of SDO/Mobile No. Length Cost Raising ning Carepet in in Km. in lacs in Km in Km Km 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Er. Anup Singh=98150-63540 Er. 1 Gurdaspur Batala SAROOPWALI TO AMRITSAR ROAD 1.05 14.54 0.07 0.98 1.05 A.B.S Engineers Amandeep Singh=7355700300 TALWANDI BHARTH TO SHAMSHAN Er. Anup Singh=98150-63540 Er. 2 Gurdaspur Batala 1.58 23.15 0.24 0.96 1.5 A.B.S Engineers GHAT UPTO PMGSY ROAD Amandeep Singh=7355700300 SAIDPUR KALAN SHAMSHANGHAT Er. Anup Singh=98150-63540 Er. 3 Gurdaspur Batala ROAD TO KASTIWAL ROAD 1.7 18.39 1.49 1.7 A.B.S Engineers Amandeep Singh=7355700300 ALONGWITH CANAL BT-FGC road to Bullowal Khokhar Er. Anup Singh=98150-63540 Er. 4 Gurdaspur Batala 2.65 26.1 1.18 2.65 A.B.S Engineers UPTO SHANKARPUR ROAD Amandeep Singh=7355700300 BATALA SGHPUR ROAD TO Er. Anup Singh=98150-63540 Er. 5 Gurdaspur Batala 1.81 21.99 1.39 1.81 C.&C Construction Co. PARTAPGARH AND PHIRNI Amandeep Singh=7355700300 BATALA,S.H.G PUR,BAHADUR- Er. Anup Singh=98150-63540 Er. 6 Gurdaspur Batala 1.31 19.35 0.42 0.73 1.31 C.&C Construction Co. HUSSAIN AND PHIRNI Amandeep Singh=7355700300 BATALA,BEAS,CHAHAL-KHURD, Er. Anup Singh=98150-63540 Er. -

Zaheeruddin V. State and the Official Persecution of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan

Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality Volume 14 Issue 1 Article 5 June 1996 Enforced Apostasy: Zaheeruddin v. State and the Official Persecution of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan M. Nadeem Ahmad Siddiq Follow this and additional works at: https://lawandinequality.org/ Recommended Citation M. N. Siddiq, Enforced Apostasy: Zaheeruddin v. State and the Officialersecution P of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan, 14(1) LAW & INEQ. 275 (1996). Available at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/lawineq/vol14/iss1/5 Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality is published by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Enforced Apostasy: Zaheeruddin v. State and the Official Persecution of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan M. Nadeem Ahmad Siddiq* Table of Contents Introduction ............................................... 276 I. The Ahmadiyya Community in Islam .................. 278 II. History of Ahmadis in Pakistan ........................ 282 III. The Decision in Zaheerudin v. State ................... 291 A. The Pakistan Court Considers Ahmadis Non- M uslim s ........................................... 292 B. Company and Trademark Laws Do Not Prohibit Ahmadis From Muslim Practices ................... 295 C. The Pakistan Court Misused United States Freedom of Religion Precedent .............................. 299 D. Ordinance XX Should Have Been Found Void for Vagueness ......................................... 314 E. The Pakistan Court Attributed False Statements to Mirza Ghulam Almad ............................. 317 F. Ordinance XX Violates -

A Message of Peace and a Word of Warning

A Message of Peace And a Word of Warning by Hadhrat Mirza Nasir Ahmad rh Khalifatul Masih III A Message of Peace and a Word of Warning A lecture delivered by Hadrat Mirza Nasir Ahmadrh, Khalifatul Masih III, on 28th July 1967, at Wandsworth Town Hall, London. © Islam International Publications Ltd. First Edition published undated by the Oriental and Religious Publishing Corporation Ltd, Rabwah, Pakistan. First Edition published in UK in 2006 First Edition Published in India in 2008 Present Edition Published in India in September 2014 Copies: 2000 Published By: Nazarat Nashr-o-Isha’at, Sadr Anjuman Ahmadiyya Qadian, Distt Gurdaspur, Punjab – 143516, India. Printed in India at: Fazle Umar Printing Press Qadian. ISBN: 978-81-7912-202-0 ABOUT THE AUTHOR rh Hadrat Hafiz Mirza Nasir Ahmad M.A. (Oxon)–1909–1982–of blessed memory, the third Manifestation of Divine Providence, the Imam of the International Ahmadiyya Muslim Jama‘at, the Voice Articulate of God, sign and fulfillment of His Promise and the Promised Grandson was elected as the third successor (Khalifa) of the Promised as Messiah and Mahdi on November 8, 1965 on the demise of his great and illustrious father, the second successor of the Promised as Messiah , Hadrat Mirza Bashirud Din ra Mahmood Ahmad , al-Muslih Ma‘ud (the Promised Reformer). He occupied this exalted spiritual station for seventeen years till his death, and as the Promised as Grandson of the Promised Messiah , he was a Sign of Allah Who bestowed on him His special Graces and Favours from the time of his birth to his death. -

UK's Largest Muslim Conference

Jalsa Salana UK UK’s Largest Muslim Conference 3 / 4 / 5 August 2018 Promoting Islam's Message of Peace Hadeeqatul Mahdi Oakland Farm Hampshire GU34 3AU www.TrueIslam.co.uk 020 8687 7871 The AHMADIYYA MUSLIM COMMUNITY THE JALSA SALANA THE AHMADIYYA MUSLIM COMMUNITY The Annual Conference (Jalsa Salana) of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community The Ahmadiyya Muslim Community UK is a unique three-day event that was founded in 1889 by Hazrat Mirza brings together more than 35,000 Ghulam Ahmad (peace be upon him) participants from over ninety countries. of Qadian, India. He claimed under Parliamentarians, diplomats, religious Divine guidance to be the Promised leaders and professionals from across Messiah and Imam Mahdi, whose the world and from all walks of life advent was awaited by the major address the gathering, the purpose religions of the world. He divested Islam of which is to foster unity between of false, fanatical teachings, revived the humanity, and with our Creator. A unique 3 day true and peaceful teachings of Islam and inspired his followers to build a A special feature of this conference event that brings strong bond with God through humble is that it is blessed by the presence together more and compassionate service to humanity. of His Holiness, Hazrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad (may Allah be his Helper), the than 35,000 Head of the worldwide Ahmadiyya Muslim Community. He addresses the participants from conference on each of the three days, over 90 countries to providing invaluable insights into the application of religious teachings to our increase religious spiritual, moral and material wellbeing. -

7 Mirza Ghulam Ahmad

7 Mirza Ghulam Ahmad In 1530, the last year of the Emperor Babar’s reign, Hadi Baig, a Mughal of Samarkand, emigra- ted to the Punjab and settled in the Gurdaspur district. He was a man of some learning and was appointed Qazi or Magistrate over 70 villages in the neighbourhood of Qadian, which town he is said to have founded, naming it Islampur Qazi, from which Qadian has by a natural change arisen. For several generations the family held offices of respectability under the Imperial Government, and it was only when the Sikhs became powerful that it fell into poverty. Gul Muhammad and his son, Ata Muhammad, were engaged in perpetual quarrels with Ramgarhia and Kanahaya Misals, who held the country in the neighbourhood of Qadian; and at last, having lost all his estates, Ata Muhammad retired to Begowal, where, under the protection of Sardar Fateh Singh Ahluvalia (ancestor of the present ruling chief of the Kapurthala State) he lived quietly for twelve years. On his death Ranjit Singh, who had taken possession of all the lands of the Ramgarhia Misal, invited Ghulam Murtaza to return to Qadian and restored to him a large portion of his ancestral estate. He then, with his brothers, entered the army of the Maharaja, and performed efficient service on the Kashmir frontier and at other places. During the time of Nao Nahal Singh and the Darbar, Ghulam Murtaza was continually employed on active service. In 1841 he was sent with General Ventura to Mandi and Kalu, and in 1843 to Peshawar in command of an infantry regiment. -

Pakistan: Massacre of Minority Ahmadis | Human Rights Watch

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH http://www.hrw.org Pakistan: Massacre of Minority Ahmadis Attack on Hospital Treating Victims Shows How State Inaction Emboldens Extremists The mosque attacks and the June 1, 2010 subsequent attack on the hospital, amid rising sectarian violence, (New York) – Pakistan’s federal and provincial governments should take immediate legal action underscore the vulnerability of the against Islamist extremist groups responsible for threats and violence against the minority Ahmadiyya Ahmadi community. religious community, Human Rights Watch said today. Ali Dayan Hasan, senior South Asia researcher On May 28, 2010, extremist Islamist militants attacked two Ahmadiyya mosques in the central Pakistani city of Lahore with guns, grenades, and suicide bombs, killing 94 people and injuring well over a hundred. Twenty-seven people were killed at the Baitul Nur Mosque in the Model Town area of Lahore; 67 were killed at the Darul Zikr mosque in the suburb of Garhi Shahu. The Punjabi Taliban, a local affiliate of the Pakistani Taliban, called the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), claimed responsibility. On the night of May 31, unidentified gunmen attacked the Intensive Care Unit of Lahore’s Jinnah Hospital, where victims and one of the alleged attackers in Friday's attacks were under treatment, sparking a shootout in which at least a further 12 people, mostly police officers and hospital staff, were killed. The assailants succeeded in escaping. “The mosque attacks and the subsequent attack on the hospital, amid rising sectarian violence, underscore the vulnerability of the Ahmadi community,” said Ali Dayan Hasan, senior South Asia researcher at Human Rights Watch.