Ring of Brodgar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University of Bradford Institutional Repository

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bradford Scholars The University of Bradford Institutional Repository http://bradscholars.brad.ac.uk This work is made available online in accordance with publisher policies. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our Policy Document available from the repository home page for further information. To see the final version of this work please visit the publisher’s website. Where available access to the published online version may require a subscription. Author(s): Gibson, Alex M. Title: An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? Publication year: 2012 Book title: Enclosing the Neolithic : Recent studies in Britain and Ireland. Report No: BAR International Series 2440. Publisher: Archaeopress. Link to publisher’s site: http://www.archaeopress.com/archaeopressshop/public/defaultAll.asp?QuickSear ch=2440 Citation: Gibson, A. (2012). An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? In: Gibson, A. (ed.). Enclosing the Neolithic: Recent studies in Britain and Europe. Oxford: Archaeopress. BAR International Series 2440, pp. 1-20. Copyright statement: © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2012. An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? Alex Gibson Abstract This paper summarises 80 years of ‘henge’ studies. It considers the range of monuments originally considered henges and how more diverse sites became added to the original list. It examines the diversity of monuments considered to be henges, their origins, their associated monument types and their dates. Since the introduction of the term, archaeologists have often been uncomfortable with it. -

The Orkney Islands the Orkney Islands

The by Carolyn Emerick Orkney Islands Let me take you down, cause we’re goin’ to... Skara Brae! The Islands of Orkney are a mystical place decline prior to the Viking invasion. Why it steeped in history and legend. Like the rest was declining is yet another mystery. It would of the British Isles, Orkney is an amalgam of appear that either the Picts required the aid of influences. The ancients left their mark from pre- Vikings, or that their situation left them wide history with their standing stones and neolithic open for a foreign invador to move in. settlements. Then came the Picts, however they What is known, is that the Viking settlement remain even more of a mystery as the Picts left of Orkney was so complete that virtually no very little evidence of their existence in Orkney place names of Pictish origin survive. In the behind. So scarce is the evidence, in fact, that rest of Britain, place names can be used to show until recently scholars questioned whether they the mixed heritage and influence of the various were there at all. It was the Vikings that left their settlers, from Celt to Roman, and especially the stamp on Orkney so strongly that their influence Germanic settlers such as the Angles, Saxons, can be found in the culture to this day. Danes, and so forth. The Vikings first began settling Orkney in the The Orkney Islands are late eighth century. From the records available, shown in Red with the we can only speculate what happened to the Shetland Islands off to Picts who had been living on the Islands prior the upper right in this to Viking settlement. -

A Pilgrimage to Avebury Stone Circles in Wiltshire

BEST OF BRITAIN A pilgrimage to Avebury stone circles in Wiltshire ere are famous religious pilgrimages, there are also the pilgrimages that one does for oneself. It doesn't have to be on foot or by any particular mode of transport. It is nothing more than the journey of getting to the desired destination, in any way or form. For me, that desired destination was the stone circles of Avebury in Wiltshire, for years I’ve been yearning to sit in stone circles and visit the sacred sites of Europe. So, why visit Avebury, a place that is often sold to us as the poor cousin of the ever-famous Stonehenge? In real - ity, it is not less but much more. Why Avebury? is sacred Neolithic site is the largest set of stone circles out of the thousands in the United Kingdom and in the world. It is older than other sites, although the dating is sketchy. I've heard everything from 2600BC to 4500BC and it’s still up for discussion. Despite being a World Heritage site, Avebury is fully open to the public. Unlike Stonehenge, you can walk in and around the stones. It is accessible by public transport, buses stop in the middle of the village, and the entrance is free. As well as the stone cir - cles, there is also an avenue of stones that take you down to the West Kennet Long Barrow and Silbury Hill. Onsite for a small fee you can visit the museum and manor that are run by the National Trust. -

Concrete Prehistories: the Making of Megalithic Modernism 1901-1939

Concrete Prehistories: The Making of Megalithic Modernism Abstract After water, concrete is the most consumed substance on earth. Every year enough cement is produced to manufacture around six billion cubic metres of concrete1. This paper investigates how concrete has been built into the construction of modern prehistories. We present an archaeology of concrete in the prehistoric landscapes of Stonehenge and Avebury, where concrete is a major component of megalithic sites restored between 1901 and 1964. We explore how concreting changed between 1901 and the Second World War, and the implications of this for constructions of prehistory. We discuss the role of concrete in debates surrounding restoration, analyze the semiotics of concrete equivalents for the megaliths, and investigate the significance of concreting to interpretations of prehistoric building. A technology that mixes ancient and modern, concrete helped build the modern archaeological imagination. Concrete is the substance of the modern –”Talking about concrete means talking about modernity” (Forty 2012:14). It is the material most closely associated with the origins and development of modern architecture, but in the modern era, concrete has also been widely deployed in the preservation and display of heritage. In fact its ubiquity means that concrete can justifiably claim to be the single most dominant substance of heritage conservation practice between 1900 and 1945. This paper investigates how concrete has been built into the construction of modern pasts, and in particular, modern prehistories. As the pre-eminent marker of modernity, concrete was used to separate ancient from modern, but efforts to preserve and display prehistoric megaliths saw concrete and megaliths become entangled. -

The Lives of Prehistoric Monuments in Iron Age, Roman, and Medieval Europe by Marta Díaz-Guardamino, Leonardo García Sanjuán and David Wheatley (Eds)

The Prehistoric Society Book Reviews THE LIVES OF PREHISTORIC MONUMENTS IN IRON AGE, ROMAN, AND MEDIEVAL EUROPE BY MARTA DÍAZ-GUARDAMINO, LEONARDO GARCÍA SANJUÁN AND DAVID WHEATLEY (EDS) Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2015. 356pp, 50 figs, 32 B/W plates, 6 tables. ISBN 978-0-19-872460-5, hb, £85 This handsome book is the outcome of a session at the 2013 European Association of Archaeologists in Pilsen, organised by the editors on the cultural biographies of monuments. It is divided into three sections, with the main part comprising 13 detailed case-studies, framed on either side by shorter introduction and discussion pieces. There is variety in the chronologies, subject matters and geographical scopes addressed; in short there is something for almost everyone! In their Introduction, the editors advocate that archaeologists require a more reflexive conceptual toolkit to deal with the complex issues of monument continuity, transformation, re-use and abandonment, and the significance of the speed and the timing of changes. They also critique the loaded term ‘afterlife’ as this separates the unfolding biography of a monument, and unwittingly relegates later activities to lesser importance than its original function. In the following chapter, Joyce Salisbury explores how the veneration of natural places in the landscape, such as caves and mountains, was shifted to man-made monumental features over time. The bulk of the book focuses on the specific case-studies which span Denmark in the north to Tunisia in the south and from Ireland in the west to Serbia and Crete in the east. In Chapter 3, Steen Hvass’s account of the history of research at the monument complex of King’s Jelling in Denmark is fascinating, but a little heavy on stratigraphic narrative, and light on theory and discussion. -

Stonehenge and Avebury WHS Management Plan 2015 Summary

Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site Management Plan Summary 2015 Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site Management Plan Summary 2015 1 Stonehenge and Avebury World Heritage Site Vision The Stonehenge and Avebury World Heritage Site is universally important for its unique and dense concentration of outstanding prehistoric monuments and sites which together form a landscape without parallel. We will work together to care for and safeguard this special area and provide a tranquil, rural and ecologically diverse setting for it and its archaeology. This will allow present and future generations to explore and enjoy the monuments and their landscape setting more fully. We will also ensure that the special qualities of the World Heritage Site are presented, interpreted and enhanced where appropriate, so that visitors, the local community and the whole world can better understand and value the extraordinary achievements © K020791 Historic England © K020791 Historic of the prehistoric people who left us this rich legacy. Avebury Stone Circle We will realise the cultural, scientific and educational potential of the World Heritage Site as well as its social and economic benefits for the community. © N060499 Historic England © N060499 Historic Stonehenge in summer 2 Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site Management Plan Summary 2015 Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site Management Plan Summary 2015 1 World Heritage Sites © K930754 Historic England © K930754 Historic Arable farming in the WHS below the Ridgeway, Avebury The Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site is internationally important for its complexes of outstanding prehistoric monuments. Stonehenge is the most architecturally sophisticated prehistoric stone circle in the world, while Avebury is Stonehenge and Avebury were inscribed as a single World Heritage Site in 1986 for their outstanding prehistoric monuments the largest. -

Stonehenge OCR Spec B: History Around Us

OCR HISTORY AROUND US Site Proposal Form Example from English Heritage The Criteria The study of the selected site must focus on the relationship between the site, other historical sources and the aspects listed in a) to n) below. It is therefore essential that centres choose a site that allows learners to use its physical features, together with other historical sources as appropriate, to understand all of the following: a) The reasons for the location of the site within its surroundings b) When and why people first created the site c) The ways in which the site has changed over time d) How the site has been used throughout its history e) The diversity of activities and people associated with the site f) The reasons for changes to the site and to the way it was used g) Significant times in the site’s past: peak activity, major developments, turning points h) The significance of specific features in the physical remains at the site i) The importance of the whole site either locally or nationally, as appropriate j) The typicality of the site based on a comparison with other similar sites k) What the site reveals about everyday life, attitudes and values in particular periods of history l) How the physical remains may prompt questions about the past and how historians frame these as valid historical enquiries m) How the physical remains can inform artistic reconstructions and other interpretations of the site n) The challenges and benefits of studying the historic environment 1 Copyright © OCR 2018 Site name: STONEHENGE Created by: ENGLISH HERITAGE LEARNING TEAM Please provide an explanation of how your site meets each of the following points and include the most appropriate visual images of your site. -

Heart of Neolithic Orkney Map and Guide

World heritage The remarkable monuments that make up the Heart of Neolithic Orkney were inscribed on the World Heritage List in 1999. These sites give visitors Heart of a vivid glimpse into the creative genius, lost beliefs and everyday lives of a once flourishing culture. Neolithic World Heritage status places them alongside such globally © Raymond Besant World heritage iconic sites as the Pyramids of Egypt and the Taj Mahal. Sites Orkney site r anger service are listed because they are of importance to all of humanity. The monuments World Heritage Site Orkney’s rich cultural and natural heritage is brought to life R anger Service Ring of Brodgar by the WHS Rangers and team of The evocative Ring of Brodgar is one of the largest and volunteers who support them. best-preserved stone circles in Great Britain. It hints at Throughout the year they run a busy programme of forgotten ritual and belief. public walks, talks and family events for all ages and Skara Brae levels of interest. The village of Skara Brae with its houses and stone Every day at 1pm in June, July and August the Rangers furniture presents an insight into the daily lives of lead walks around the Ring of Brodgar to explore the Neolithic people that is unmatched in northern Europe. iconic monument and its surrounding landscape. There Stones of Stenness are also activities designed specifically for schools and education groups. The Stones of Stenness are the remains of one of the oldest stone circles in the country, raised about 5,000 years ago. The Rangers work closely with the local community to care for the historical landscape and the wildlife that Maeshowe lives in and around its monuments. -

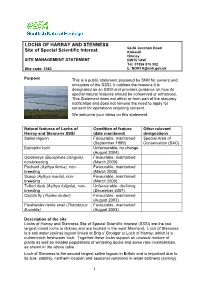

Lochs of Harray and Stenness Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) Are the Two Largest Inland Lochs in Orkney and Are Located in the West Mainland

LOCHS OF HARRAY AND STENNESS 54-56 Junction Road Site of Special Scientific Interest Kirkwall Orkney SITE MANAGEMENT STATEMENT KW15 1AW Tel: 01856 875 302 Site code: 1083 E: [email protected] Purpose This is a public statement prepared by SNH for owners and occupiers of the SSSI. It outlines the reasons it is designated as an SSSI and provides guidance on how its special natural features should be conserved or enhanced. This Statement does not affect or form part of the statutory notification and does not remove the need to apply for consent for operations requiring consent. We welcome your views on this statement. Natural features of Lochs of Condition of feature Other relevant Harray and Stenness SSSI (date monitored) designations Saline lagoon Favourable, maintained Special Area of (September 1999) Conservation (SAC) Eutrophic loch Unfavourable, no change (August 2004) Goldeneye (Bucephala clangula), Favourable, maintained non-breeding (March 2000) Pochard (Aythya ferina), non- Favourable, maintained breeding (March 2000) Scaup (Aythya marila), non- Favourable, maintained breeding (March 2000) Tufted duck (Aythya fuligula), non- Unfavourable, declining breeding (December 2007) Caddis fly (Ylodes reuteri) Favourable, maintained (August 2003) Freshwater nerite snail (Theodoxus Favourable, maintained fluviatilis) (August 2003) Description of the site Lochs of Harray and Stenness Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) are the two largest inland lochs in Orkney and are located in the west Mainland. Loch of Stenness is a salt water (saline) lagoon linked at Brig o’ Brodgar to Loch of Harray, which is a nutrient-rich freshwater loch. Together these lochs support an unusual mixture of plants as well as notable populations of wintering ducks and some rare invertebrates, as shown in the above table. -

How to Tell a Cromlech from a Quoit ©

How to tell a cromlech from a quoit © As you might have guessed from the title, this article looks at different types of Neolithic or early Bronze Age megaliths and burial mounds, with particular reference to some well-known examples in the UK. It’s also a quick overview of some of the terms used when describing certain types of megaliths, standing stones and tombs. The definitions below serve to illustrate that there is little general agreement over what we could classify as burial mounds. Burial mounds, cairns, tumuli and barrows can all refer to man- made hills of earth or stone, are located globally and may include all types of standing stones. A barrow is a mound of earth that covers a burial. Sometimes, burials were dug into the original ground surface, but some are found placed in the mound itself. The term, barrow, can be used for British burial mounds of any period. However, round barrows can be dated to either the Early Bronze Age or the Saxon period before the conversion to Christianity, whereas long barrows are usually Neolithic in origin. So, what is a megalith? A megalith is a large stone structure or a group of standing stones - the term, megalith means great stone, from two Greek words, megas (meaning: great) and lithos (meaning: stone). However, the general meaning of megaliths includes any structure composed of large stones, which include tombs and circular standing structures. Such structures have been found in Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, North and South America and may have had religious significance. Megaliths tend to be put into two general categories, ie dolmens or menhirs. -

4. Vocabulary Cards Rectificado

n. someone who studies the past by recovering and examining remaining material evidence, such archaeologist as graves, buildings, tools, bones and pottery. “ The archaeologist excavated the site.” n. the study of past human life and culture by the recovery and examination of remaining evidence, such archaeology as graves, buildings, bones and pottery. n. someone who lives in a cave. “Prehistoric man found cave dweller shelter in caves. They became cave dwellers.” n. representations of wild, animals, painted on the walls of caves by prehistoric people, using cave painting simple tools such as fingers, twigs and leaves and using colours found in nature such as brown, red, black and green. adj. relating to the period in human culture before the bronze age, characterised by the chalcolithic use of copper and stone. “The bones were dug up at a chalcolithic site. There were bronze tools there, too.” adj. early form of modern human inhabiting Europe in the late paleolithic period (40,000 – 10,000 years cro-magnon ago). Skeletal remains were first found in the Cro- Magnon cave in southern France. “Homo Sapiens is a cro.magnon man.” n. structure usually regarded as a tomb, dolmen consisting of two or more large upright stones set with a space between and capped by a horizontal stone. n. place where archaeologists dig to find evidence of how excavation site humans lived in the past. “The excavation site is full of interesting things we can use to find out about the past.” n. very hard fine- grained quartz that spark when struck. Prehistoric people used flint this to make tools and start fire. -

The Significance of the Ancient Standing Stones, Villages, Tombs on Orkney Island

The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism Volume 5 Print Reference: Pages 561-572 Article 43 2003 The Significance of the Ancient Standing Stones, Villages, Tombs on Orkney Island Lawson L. Schroeder Philip L. Schroeder Bryan College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Browse the contents of this volume of The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism. Recommended Citation Schroeder, Lawson L. and Schroeder, Philip L. (2003) "The Significance of the Ancient Standing Stones, Villages, Tombs on Orkney Island," The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism: Vol. 5 , Article 43. Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings/vol5/iss1/43 THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE ANCIENT STANDING STONES, VILLAGES AND TOMBS FOUND ON THE ORKNEY ISLANDS LAWSON L. SCHROEDER, D.D.S. PHILIP L. SCHROEDER 5889 MILLSTONE RUN BRYAN COLLEGE STONE MOUNTAIN, GA 30087 P. O. BOX 7484 DAYTON, TN 37321-7000 KEYWORDS: Orkney Islands, ancient stone structures, Skara Brae, Maes Howe, broch, Ring of Brodgar, Standing Stones of Stenness, dispersion, Babel, famine, Ice Age ABSTRACT The Orkney Islands make up an archipelago north of Scotland.