Almost Nothing with Luc Ferrari

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KURT WEILL NEWSLETTER Volume 5, Number 2 Fall 1987

KURT WEILL NEWSLETTER Volume 5, Number 2 Fall 1987 AMTF Receives Federal Grant for university production is reviewed in this Love Life issue). The grant represents part of the The American Music Theater Festival NEA's six-million dollar effort to assist recently received an $80,000 grant from opera and musical theater companies the National Endowment for the Arts to throughout the United States. Other support its 1988 planned production of recipients include the Metropolitan and l Love Life and to assist in rehearsals of New York City Operas (in support of Revelation of the Courthouse Park, by the their free summer programs), the Hous pioneering microtonal composer, Harry ton Grand Opera, the Lyric Opera of Partch. The AMTF production of the Chicago, the Opera Guild of Greater Weill-Lerner collaboration will mark the Miami, and the Washington, DC, Na first professional revival of the work (a tional Institute for Music Theater. IN THIS ISSUE Say No to Mediocrity: The Crisis of Musical Interpretation by 6 Kurt Weill Love Life Begins at Forty by Terry Millei· 8 The Seven Deadly Sins at Brighton by Jane P1itchard 10 Columns Letters: David Drew Answers Richard Taruskin 3 Around the World: Kurt Weill Festival in New York 4 I Remember: Your Place, Or Mine?: An "un-German" Affair by 5 David Drew's Handbook Published Felix Jackson New Publications in UK and US 12 Selected Performances 23 Kurt Weill: A Handbook by David Drew was published in September by Reviews Faber and Faber in the United Kingdom Kurt Weill Festival in New York Allan Kozinn 13 and the University of California Press in Seven Deadly Sins in London Paul Meecham 16 the United States. -

Through the Iris TH Wasteland SC Because the Night MM PS SC

10 Years 18 Days Through The Iris TH Saving Abel CB Wasteland SC 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10,000 Maniacs 1,2,3 Redlight SC Because The Night MM PS Simon Says DK SF SC 1975 Candy Everybody Wants DK Chocolate SF Like The Weather MM City MR More Than This MM PH Robbers SF SC 1975, The These Are The Days PI Chocolate MR Trouble Me SC 2 Chainz And Drake 100 Proof Aged In Soul No Lie (Clean) SB Somebody's Been Sleeping SC 2 Evisa 10CC Oh La La La SF Don't Turn Me Away G0 2 Live Crew Dreadlock Holiday KD SF ZM Do Wah Diddy SC Feel The Love G0 Me So Horny SC Food For Thought G0 We Want Some Pussy SC Good Morning Judge G0 2 Pac And Eminem I'm Mandy SF One Day At A Time PH I'm Not In Love DK EK 2 Pac And Eric Will MM SC Do For Love MM SF 2 Play, Thomas Jules And Jucxi D Life Is A Minestrone G0 Careless Whisper MR One Two Five G0 2 Unlimited People In Love G0 No Limits SF Rubber Bullets SF 20 Fingers Silly Love G0 Short Dick Man SC TU Things We Do For Love SC 21St Century Girls Things We Do For Love, The SF ZM 21St Century Girls SF Woman In Love G0 2Pac 112 California Love MM SF Come See Me SC California Love (Original Version) SC Cupid DI Changes SC Dance With Me CB SC Dear Mama DK SF It's Over Now DI SC How Do You Want It MM Only You SC I Get Around AX Peaches And Cream PH SC So Many Tears SB SG Thugz Mansion PH SC Right Here For You PH Until The End Of Time SC U Already Know SC Until The End Of Time (Radio Version) SC 112 And Ludacris 2PAC And Notorious B.I.G. -

Songs by Artist

73K October 2013 Songs by Artist 73K October 2013 Title Title Title +44 2 Chainz & Chris Brown 3 Doors Down When Your Heart Stops Countdown Let Me Go Beating 2 Evisa Live For Today 10 Years Oh La La La Loser Beautiful 2 Live Crew Road I'm On, The Through The Iris Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I'm Gone Wasteland Me So Horny When You're Young 10,000 Maniacs We Want Some P---Y! 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Because The Night 2 Pac Landing In London Candy Everybody Wants California Love 3 Of A Kind Like The Weather Changes Baby Cakes More Than This Dear Mama 3 Of Hearts These Are The Days How Do You Want It Arizona Rain Trouble Me Thugz Mansion Love Is Enough 100 Proof Aged In Soul Until The End Of Time 30 Seconds To Mars Somebody's Been Sleeping 2 Pac & Eminem Closer To The Edge 10cc One Day At A Time Kill, The Donna 2 Pac & Eric Williams Kings And Queens Dreadlock Holiday Do For Love 311 I'm Mandy 2 Pac & Notorious Big All Mixed Up I'm Not In Love Runnin' Amber Rubber Bullets 2 Pistols & Ray J Beyond The Gray Sky Things We Do For Love, The You Know Me Creatures (For A While) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Pistols & T Pain & Tay Dizm Don't Tread On Me We Do For Love She Got It Down 112 2 Unlimited First Straw Come See Me No Limits Hey You Cupid 20 Fingers I'll Be Here Awhile Dance With Me Short Dick Man Love Song It's Over Now 21 Demands You Wouldn't Believe Only You Give Me A Minute 38 Special Peaches & Cream 21st Century Girls Back Where You Belong Right Here For You 21St Century Girls Caught Up In You U Already Know 3 Colours Red Hold On Loosely 112 & Ludacris Beautiful Day If I'd Been The One Hot & Wet 3 Days Grace Rockin' Into The Night 12 Gauge Home Second Chance Dunkie Butt Just Like You Teacher, Teacher 12 Stones 3 Doors Down Wild Eyed Southern Boys Crash Away From The Sun 3LW Far Away Be Like That I Do (Wanna Get Close To We Are One Behind Those Eyes You) 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Nicola Candlish Phd 2012

Durham E-Theses The Development of Resources for Electronic Music in the UK, with Particular Reference to the bids to establish a National Studio CANDLISH, NICOLA,ANNE How to cite: CANDLISH, NICOLA,ANNE (2012) The Development of Resources for Electronic Music in the UK, with Particular Reference to the bids to establish a National Studio, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3915/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 ‘The Development of Resources for Electronic Music in the UK, with Particular Reference to the bids to establish a National Studio’ Nicola Anne Candlish Doctor of Philosophy Music Department Durham University 2012 Nicola Anne Candlish ‘The Development of Resources for Electronic Music in the UK, with Particular Reference to the Bids to Establish a National Studio’ This thesis traces the history and development of the facilities for electronic music in the UK. -

Cirque Dreams: Illumination by Neil Goldberg, Jill Winters & David Scott

Young Critics Reviews Fall 2010-2011 Cirque Dreams: Illumination By Neil Goldberg, Jill Winters & David Scott At the Hippodrome Theatre through October 17 By Aaron Bell ILLUMINATION SHOWS ITS BRILLIANCE The house lights go down in the historic Hippodrome Theatre. We’re brought into a fast-paced newscast program when we hear the superbly resonant voice of Onyie Nwachukwu, who plays the Reporter. She tells us that another regular day has just begun, and that the daily occurrences in the “Cirque Dreams: Illumination” world will soon be lighting up the stage. Although a tad disturbed by her slightly nasal, high-belting, soulful vocals, one comes to appreciate Nwachukwu’s stylized singing; it completely fits her fun-loving, scoop-seeking reporter essence. One can’t help but appreciate her wonderful articulation and vocal clarity when she serenades us with a fabulously written opening number. This song, “Change,” gives us the main idea of the entire show, “If you don’t like it, change your mind. ” One’s mind is indeed changed by this sparkly production. The many feats of physical excellence and theatrical genius suggest how everyday life would look with an incredibly heightened sense of imagination. Santiago Rojo’s costume design and Betsy Herst’s production design bring that concept to life with their explosively colorful and symbolic wardrobes and sets. One sees cast members dressed as animated street cones, traffic lights and construction items. The set uses neon effects to brighten up the town atmosphere. The characters’ relationships with each other and their environment are interesting elements as well. -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Destination Freedom: Strategies for Immersion in Narrative Soundscape Composition Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/84w212wq Author Jackson, Yvette Janine Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Destination Freedom: Strategies for Immersion in Narrative Soundscape Composition A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Yvette Janine Jackson Committee in charge: Professor Anthony Davis, Chair Professor Anthony Burr Professor Amy Cimini Professor Miller Puckette Professor Clinton Tolley Professor Shahrokh Yadegari 2017 Copyright Yvette Janine Jackson, 2017 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Yvette Janine Jackson is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2017 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page .................................................................................................... iii Table of Contents ............................................................................................... iv List of Supplemental Files ................................................................................... v List of Tables ...................................................................................................... vi List of -

The Construction of Listening in Electroacoustic Music Discourse

Learning to Listen: The Construction of Listening in Electroacoustic Music Discourse Michelle Melanie Stead School of Humanities and Communication Arts Western Sydney University. September, 2016 A thesis submitted as fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Western Sydney University. To the memories of my father, Kenny and my paternal grandmother, Bertha. <3 Acknowledgements Firstly, to Western Sydney University for giving me this opportunity and for its understanding in giving me the extra time I needed to complete. To my research supervisors, Associate Professor Sally Macarthur and Dr Ian Stevenson: This thesis would not have been possible without your mentorship, support, generosity, encouragement, guidance, compassion, inspiration, advice, empathy etc. etc. … The list really is endless. You have both extended your help to me in different ways and you have both played an essential role in my development as an academic, teacher and just ... as a human being. You have both helped me to produce the kind of dissertation of which I am extremely proud, and that I feel is entirely worth the journey that it has taken. A simple thank you will never seem enough. To all of the people who participated in my research by responding to the surveys and those who agreed to be interviewed, I am indebted to your knowledge and to your expertise. I have learnt that it takes a village to write a PhD and, along with the aforementioned, ‗my people‘ have played a crucial role in the development of this research that is as much a personal endeavour as it is a professional one. -

On Luc Ferrari's Complete Music for Films 1960-1984, Via Sub Rosa – The

on luc ferrari’s complete music for films 1960-1984, via sub rosa... https://blogthehum.wordpress.com/2017/11/06/on-luc-ferraris-c... Menu The Hum Blog a blog for the-hum.com bradfordbailey in Uncategorized November 6, 2017 608 Words on luc ferrari’s complete music for films 1960-1984, via sub rosa 1 sur 4 09/11/2017 à 18:22 on luc ferrari’s complete music for films 1960-1984, via sub rosa... https://blogthehum.wordpress.com/2017/11/06/on-luc-ferraris-c... Luc Ferrari – Complete Music For Films 1960-1984 (2017) Within the history of avant-garde and experimental electronic music, there are few names as significant as Luc Ferrari – a towering figure of musical Modernism, who elevated the field to unforeseen heights. Ferrari trained as a classical pianist under Alfred Cortot, while studying theory under Olivier Messiaen and composition with Arthur Honegger – an incredible pedigree, before shifting his interests toward magnetic tape and electronics following an encounter with Edgard Varèse’s Déserts. Between the late 1950s and 1966, he collaborated extensively within Groupe de Musique Concrete, concurrently founding Groupe de Recherches Musicales with Pierre Schaeffer in 1958 – a collective and studio which holds a singular and iconic place within the history of avant- garde electronic music. Ferrari’s work between the late 50’s and his death in 2005 is stunning. There are few parallels within the same period. Strikingly diverse in process and application, his music is filled with a belief in the importance of all sound, and the avant-garde’s potential to effect positive change on everyday life. -

Grammy Award and American Idol Winner Fantasia to Perform “Ugly” on Series Finale of American Idol on April 7

GRAMMY AWARD AND AMERICAN IDOL WINNER FANTASIA TO PERFORM “UGLY” ON SERIES FINALE OF AMERICAN IDOL ON APRIL 7 RON FAIR-PRODUCED “UGLY” TO APPEAR ON FANTASIA’S FORTHCOMING FIFTH STUDIO ALBUM, ‘THE DEFINITION OF…’ CLICK HERE HERE TO LISTEN TO “UGLY” [New York, NY – April 6, 2016] Grammy Award and third season American Idol winner FANTASIA returns to the American Idol stage for their last bow on the series finale on April 7. The High Point, NC native will make her national debut performance of “Ugly,” a song from her forthcoming album The Definition Of… Written by Audra Mae and Nicolle Galyon, and produced by Ron Fair, “Ugly” will be available for purchase at all digital music providers at midnight on April 7th. Click here to listen to “Ugly.” The Definition Of… is the follow up to Fantasia’s 2013 LP, Side Effects Of You, which debuted at #1 on the Billboard R&B Albums Chart and #2 on the Billboard Top 200, marking her second consecutive positions on these charts. Slated for release this summer on 19 Recordings/RCA Records, The Definition Of… will feature Fantasia’s current Top 10 single “No Time For It.” Beginning April 21 at Shea’s Buffalo Theatre in Buffalo, NY, Fantasia will hit the road with fellow Grammy Award winner and RCA Records label mate Anthony Hamilton on their co-headlining tour. Fans can expect to hear all of their hits plus new music from Fantasia’s forthcoming album and Anthony’s recently released What I'm Feelin'. More About FANTASIA: In 2004, the High Point, North Carolina native became the season three winner of Fox’s American Idol. -

A Personal and Fragile Affair: the Sonic Environment and Its Place in My Compositions

A Personal and Fragile Affair: the sonic environment and its place in my compositions by Thomas Voyce, October 2009 A thesis submitted to the New Zealand School of Music in the fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Music in Composition 2009 1 Contents: Introduction Page 4 Overview Page 9 My Practice Page 10 Listening Page 11 Recording Page 12 Playback Page 14 Transformation Page 15 Presentation Page 17 Questions Page 19 Recording and Reproduction Page 20 The Art of Noises Page 23 Musique Concrète Page 31 Almost Nothing Page 42 The World Soundscape Project Page 46 Soundscape as Composition Page 52 Soundscape Composition Page 59 Soundscape Composition Versus Musique Concrète? Page 62 2 Contents (continued) Tensions Page 65 The Composer Page 66 Listening Page 72 Indicative Relationships Page 78 A Personal and Fragile Affair Page 84 Programme Notes Page 92 Bibliography Page 97 3 A Personal and Fragile Affair: the sonic environment and its place in my compositions by Thomas Voyce, October 2009 Introduction In 1999, while studying composition at the Victoria University School of Music in Wellington, I was working part-time as a security guard at the Wellington International Airport. The airport had not yet opened, and while there was electricity to most of the building, the main electronic doors were not powered, wide open and posing a security risk at night. I was positioned there for about a week, working alone from 9 at night until 6 in the morning. I would get a few hours sleep before attending classes, and then repeat the process. -

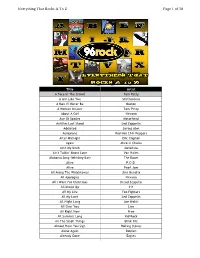

Of 30 Everything That Rocks a to Z

Everything That Rocks A To Z Page 1 of 30 Title Artist A Face In The Crowd Tom Petty A Girl Like You Smithereens A Man I'll Never Be Boston A Woman In Love Tom Petty About A Girl Nirvana Ace Of Spades Motorhead Achilles Last Stand Led Zeppelin Addicted Saving Abel Aeroplane Red Hot Chili Peppers After Midnight Eric Clapton Again Alice In Chains Ain't My Bitch Metallica Ain't Talkin' About Love Van Halen Alabama Song (Whiskey Bar) The Doors Alive P.O.D. Alive Pearl Jam All Along The Watchtower Jimi Hendrix All Apologies Nirvana All I Want For Christmas Dread Zeppelin All Mixed Up 311 All My Life Foo Fighters All My Love Led Zeppelin All Night Long Joe Walsh All Over You Live All Right Now Free All Summer Long Kid Rock All The Small Things Blink 182 Almost Hear You Sigh Rolling Stones Alone Again Dokken Already Gone Eagles Everything That Rocks A To Z Page 2 of 30 Always Saliva American Bad Ass Kid Rock American Girl Tom Petty American Idiot Green Day American Woman Lenny Kravitz Amsterdam Van Halen And Fools Shine On Brother Cane And Justice For All Metallica And The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen Angel Aerosmith Angel Of Harlem U2 Angie Rolling Stones Angry Chair Alice In Chains Animal Def Leppard Animal Pearl Jam Animal I Have Become Three Days Grace Animals Nickelback Another Brick In The Wall Pt. 2 Pink Floyd Another One Bites The Dust Queen Another Tricky Day The Who Anything Goes AC/DC Aqualung Jethro Tull Are You Experienced? Jimi Hendrix Are You Gonna Be My Girl Jet Are You Gonna Go My Way Lenny Kravitz Armageddon It Def Leppard Around -

Narcotics Anonymous

NARCOTICS ANONYMOUS Fifth Edition Contents NARCOTICS ANONYMOUS ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 OUR SYMBOL ................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 WHO IS AN ADDICT? ..................................................................................................................................................................... 8 WHY ARE WE HERE? ................................................................................................................................................................... 14 HOW IT WORKS .......................................................................................................................................................................... 16 STEP ONE .................................................................................................................................................................................... 17 STEP TWO ................................................................................................................................................................................... 19 STEP THREE ................................................................................................................................................................................. 21 STEP FOUR .................................................................................................................................................................................