Collections at the IPM by Rob Strachan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Jazz Rag

THE JAZZ RAG ISSUE 140 SPRING 2016 EARL HINES UK £3.25 CONTENTS EARL HINES A HIGHLY IMPRESSIVE NEW COLLECTION OF THE MUSIC OF THE GREAT JAZZ PIANIST - 7 CDS AND A DVD - ON STORYVILLE RECORDS IS REVIEWED ON PAGE 30. 4 NEWS 7 UPCOMING EVENTS 8 JAZZ RAG CHARTS NEW! CDS AND BOOKS SALES CHARTS 10 BIRMINGHAM-SOLIHULL JAZZ FESTIVALS LINK UP 11 BRINGING JAZZ TO THE MILLIONS JAZZ PHOTOGRAPHS AT BIRMINGHAM'S SUPER-STATION 12 26 AND COUNTING SUBSCRIBE TO THE JAZZ RAG A NEW RECORDING OF AN ESTABLISHED SHOW THE NEXT SIX EDITIONS MAILED 14 NEW BRANCH OF THE JAZZ ARCHIVE DIRECT TO YOUR DOOR FOR ONLY NJA SOUTHEND OPENS £17.50* 16 THE 50 TOP JAZZ SINGERS? Simply send us your name. address and postcode along with your payment and we’ll commence the service from the next issue. SCOTT YANOW COURTS CONTROVERSY OTHER SUBSCRIPTION RATES: EU £20.50 USA, CANADA, AUSTRALIA £24.50 18 JAZZ FESTIVALS Cheques / Postal orders payable to BIG BEAR MUSIC 21 REVIEW SECTION Please send to: LIVE AT SOUTHPORT, CDS AND FILM JAZZ RAG SUBSCRIPTIONS PO BOX 944 | Birmingham | England 32 BEGINNING TO CD LIGHT * to any UK address THE JAZZ RAG PO BOX 944, Birmingham, B16 8UT, England UPFRONT Tel: 0121454 7020 FESTIVALS IN PERIL Fax: 0121 454 9996 Email: [email protected] In his latest Newsletter Chris Hodgkins, former head of Jazz Services, heads one item, ‘Ealing Jazz Festival under Threat’. He explains that the festival previously ran for eight Web: www.jazzrag.com days with 34 main stage concerts, then goes on: ‘Since outsourcing the management of the festival to a private contractor the Publisher / editor: Jim Simpson sponsorships have ended, admission charges have been introduced and now it is News / features: Ron Simpson proposed to cut the Festival to just two days. -

Wealthy Business Families in Glasgow and Liverpool, 1870-1930 a DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY In Trade: Wealthy Business Families in Glasgow and Liverpool, 1870-1930 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Field of History By Emma Goldsmith EVANSTON, ILLINOIS December 2017 2 Abstract This dissertation provides an account of the richest people in Glasgow and Liverpool at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries. It focuses on those in shipping, trade, and shipbuilding, who had global interests and amassed large fortunes. It examines the transition away from family business as managers took over, family successions altered, office spaces changed, and new business trips took hold. At the same time, the family itself underwent a shift away from endogamy as young people, particularly women, rebelled against the old way of arranging marriages. This dissertation addresses questions about gentrification, suburbanization, and the decline of civic leadership. It challenges the notion that businessmen aspired to become aristocrats. It follows family businessmen through the First World War, which upset their notions of efficiency, businesslike behaviour, and free trade, to the painful interwar years. This group, once proud leaders of Liverpool and Glasgow, assimilated into the national upper-middle class. This dissertation is rooted in the family papers left behind by these families, and follows their experiences of these turbulent and eventful years. 3 Acknowledgements This work would not have been possible without the advising of Deborah Cohen. Her inexhaustible willingness to comment on my writing and improve my ideas has shaped every part of this dissertation, and I owe her many thanks. -

Toto's Shannon Forrest

WORTH WIN A TAMA/MEINL PACKAGE MORE THAN $6,000 THE WORLD’S #1 DRUM MAGAZINE 25 GR E AT ’80s DRUM TRACKS Toto’s Shannon ForrestThe Quest For Excellence NEW GEAR REVIEWED! BOSPHORUS • ROLAND • TURKISH OCTOBER 2016 + PLUS + STEVEN WOLF • CHARLES HAYNES • NAVENE KOPERWEIS WILL KENNEDY • BUN E. CARLOS • TERENCE HIGGINS PURE PURPLEHEARTTM 12 Modern Drummer June 2014 CALIFORNIA CUSTOM SHOP Purpleheart Snare Ad - 6-2016 (MD).indd 1 7/22/16 2:33 PM ILL SURPRISE YOU & ILITY W THE F SAT UN VER WIL HE L IN T SP IR E Y OU 18" AA SICK HATS New Big & Ugly Big & Ugly is all about sonic Thin and very dry overall, 18" AA Sick Hats are 18" AA Sick Hats versatility, tonal complexity − surprisingly controllable. 28 holes allow them 14" XSR Monarch Hats and huge fun. Learn more. to breathe in ways other Hats simply cannot. 18" XSR Monarch With virtually no airlock, you’ll hear everything. 20" XSR Monarch 14" AA Apollo Hats Want more body, less air in your face, and 16" AA Apollo Hats the ability to play patterns without the holes 18" AA Apollo getting in your way? Just flip ‘em over! 20" AA Apollo SABIAN.COM/BIGUGLY Advertisement: New Big & Ugly Ad · Publication: Modern Drummer · Trim Size: 7.875" x 10.75" · Date: 2015 Contact: Luis Cardoso · Tel: (506) 272.1238 · Fax: (506) 272.1265 · Email: [email protected] SABIAN Ltd., 219 Main St., Meductic, NB, CANADA, E6H 2L5 YOUR BEST PERFORMANCE STARTS AT THE CORE At the core of every great performance is Carl Palmer's confidence—Confidence in your ability, your SIGNATURE 20" DUO RIDE preparation & your equipment. -

Eric Hobsbawm and All That Jazz RICHARD J

Eric Hobsbawm and all that jazz RICHARD J. EVANS The latest annual collection of Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the British Academy, published in December 2015, includes an extended obituary of Eric Hobsbawm (1917-2012), written by Professor Sir Richard Evans FBA. Hobsbawm was one of the UK’s most renowned modern historians and left-wing public intellectuals. His influential three-volume history of the 19th and 20th centuries, published between 1962 and 1987, put a new concept on the historiographical map: ‘the long 19th century’. The full obituary may be found via www.britishacademy.ac.uk/memoirs/14/ This extract from the obituary reveals Eric Hobsbawm’s less well-known interest in jazz. here seemed to be no problem in Eric’s combining his post at Birkbeck College [University of London] Twith his Fellowship at King’s College Cambridge, but when the latter came to an end in 1954 he moved permanently to London, occupying a large flat in Torrington Place, in Bloomsbury, close to Birkbeck, which he shared over time with a variety of Communist or ex- Communist friends. Gradually, as he emerged from the depression that followed the break-up of his marriage, he began a new lifestyle, in which the close comradeship and sense of identity he had found in the Communist movement was, above all from 1956 onwards, replaced by an increasingly intense involvement with the world of jazz. Already before the war his cousin Denis Preston had played records by Louis Armstrong, Bessie Smith and other musicians to him on a wind-up gramophone Eric Hobsbawm (1917-2012) was elected a Fellow of the British Academy in Preston’s mother’s house in Sydenham. -

Clanger Bedford

OCTOBER 2017 THEBEDFORDCLANGER.COM THE BEDFORD YOUR CULTURAL GUIDE TO CLANGERTHE BEST OF BEDFORD Inside: BEDPOP FUN PALACES BEDFORD BEER FESTIVAL 40TH ANNIVERSARY MR X STITCH MAGAZINE LAUNCH EXTRAVAGANZA MOULIN ROUGE SCREENING Letter from Team Clanger Woo hoo! Autumn is here and we’re back from our summer break. There’s lots to look forward to this month, from amazing theatre and live music to BedPop Fun Palaces and Bromham Apple Day. Why not raise a glass and help celebrate the 40th anniversary of Bedford Beer Festival at the Corn Exchange on 4th – 7th October? If you’re 40 during the festival, you can claim a free pint! We’ve also got the lowdown on The Frog (the newest addition to Riverside Square) and Gareth Barber’s Best of Bedford. Finally, we can’t sign off without saying a very fond farewell to The Pad nightclub. A stalwart of Lurke Street for 15 years, the building is now under new management, but our memories will live on. Team Clanger THE CLANGER NEWS IN BRIEF Team Clanger Pomaceous, dude! Editor: Erica Roffe @bedfordclanger 15 October 10:30 am - 4:00 pm [email protected] The ever-popular Apple Day returns to Bromham Commercial Manager: Julia Crofts @clangerads Mill on Sunday 15th October 2017. Visitors can expect [email protected] a range of fun and traditional activities to celebrate Design: Adam Boreham @reactionvm all things pomaceous.* On-site there will be a wide reactionvisual.media selection of food and drink (including cider) and lots Photography: Cat Lane @catlanephoto of fun-filled activities for the whole family to enjoy. -

Sherman Robertson Band Chris Jagger's Atacha!

OCTOBER 2009 NOVEMBER 2009 Fri 2 Sun 1 Sherman Robertson Band Afternoon Tea Party (1pm till 6pm) £10adv £12door £5 feat. Mortiarty, The Hi and Lo, Giles Likes Tea, Sherman Robertson is a master of hard-swinging Texas electric The Gadjos, Matthew & The Echos and Richard Walters. blues. “I use that driving, zydeco groove and put blues on top of Moriarty are not your average indie-rock band or streamlined it,” says Robertson. “When I first saw him he was on fire. He ruled electro-pop unit. With members of French, American, Swiss and the stage and reminded me of Albert Collins. He’s got that Texas Vietnamese parentage, they’re a ramshackle olde worlde acoustic energy, great guitar chops and is a wonderful, soulful singer.”- outfit with a theatrical bent and a tendency to dress like 1930s Bruce Iglauer, Alligator Records. www.movinmusic.co.uk Prohibition outlaws and a sound that takes in folk, country, blues, jazz and cabaret. www.myspace.com/moriartylands Thu 8 Wed 4 Chris Jagger’s Atacha! Johnny Dickinson & Paul Lamb £8adv £10door £8adv/ £10door plus Paul Cowley Founded in 1994, Chris Jagger’s Atcha! are now hotter than ever Johnny Dickinson has been called the most potent slide player in and are one of very few UK bands that can handle cajun, R&B, the UK. Johnny was a founder member of Paul Lamb’s acclaimed zydeco, blues and country in an authentic and original fashion. band The Kingsnakes. Hailed by both aficionados and the music Chris is backed by a band of great musicians. -

2 to Be Somebody: Ambition and the Desire to Be Different

2 To Be Somebody: Ambition and the Desire to Be Different The context for difference This chapter aims to identify some of the bands that enjoyed chart success during the late 1970s and ’80s and identify their artistic traits by means of conversations with band members and those close to the bands. This chapter does not claim to be a definitive account or an inclusive list of innovative bands but merely a viewpoint from some of the individuals who were present at the time and involved in music, creativity and youth culture. Some of these individuals were in the eye of the storm while others were more on the periphery. However, common themes emerge and testify to the Scouse resilience identified in the previous chapter. Also, identifying objective truth is a difficult task, as one band member will often have a view of his band’s history that conflicts with that of other members of the same band. As such, it is acknowledged that this chapter presents only selective viewpoints. Trying something new: In what ways were the Liverpool bands creative and different? ‘Liverpool has always made me brave, choice-wise. It was never a city that criticized anyone for taking a chance.’ David Morrissey1 In terms of creativity, the theory underpinning this book which was stated in Chapter 1 is that successful Liverpool bands in the 1980s were different from each other and did not attempt to follow the latest local or national pop music trends. None of the bands interviewed falls into the categories of punk, disco or New Romantic, which were popular trends at the time. -

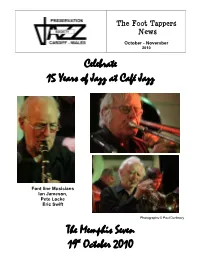

October 2010 E-Mail

The Foot Tappers News October - November 2010 Celebrate 15 Years of Jazz at Café Jazz Font line Musicians Ian Jameson, Pete Locke Eric Swift Photographs © Paul Dunleavy The Memphis Seven 19th October 2010 e-mail :- Editorial [email protected] Tel :- 029 20625639 September 2010 In October we celebrate 15 years of presentations at Café Jazz and to mark this we have some of your favourite bands plus a new band to us from London – more about them later. In those 15 years we have had the 10th Avenue Band and the Black Eagle Bands as well as Jim Beatty, Jeff Barnhart, and Jim Fryer from the USA, Mysto’s Hot Lips Band form Sweden, the late Tommy Burton, Phil Mason. Spats Langham, Roy Williams, John Barnes and numerous others from the UK as well as our great local musicians. The Adamant, Marching Band played at Brecon Cathedral to a packed congregation and then paraded to the Castle Hotel via the town with the Dean adopting the role of Parade Marshal. I assume the festival went ahead, but a walk through town showed little or no festival activity. Well done “The fringe” for providing some excellent music, personally I think that they should have the Arts Council funding as at least they tried to get back to the roots of the festival in providing music by Welsh musicians and involving the local community. A reminder for those who like to come to Café Jazz by car. You can park your car in the new St David’s Car Park, at the John Lewis Store, for £1.00. -

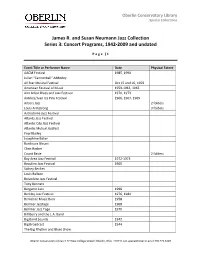

James R. and Susan Neumann Jazz Collection Series 3: Concert Programs, 1942-2009 and Undated

Oberlin Conservatory Library Special Collections James R. and Susan Neumann Jazz Collection Series 3: Concert Programs, 1942-2009 and undated P a g e | 1 Event Title or Performer Name Date Physical Extent AACM Festival 1985, 1990 Julian "Cannonball" Adderley All Star Musical Festival Oct 15 and 16, 1959 American Festival of Music 1959-1963, 1965 Ann Arbor Blues and Jazz Festival 1970, 1973 Antibes/Juan les Pins Festival 1966, 1967, 1969 Arbors Jazz 2 folders Louis Armstrong 3 folders Astrodome Jazz Festival Atlanta Jazz Festival Atlantic City Jazz Festival Atlantic Mutual Jazzfest Pearl Bailey Josephine Baker Banlieues Bleues Chris Barber Count Basie 2 folders Bay Area Jazz Festival 1972-1973 Beaulieu Jazz Festival 1960 Sidney Bechet Louis Bellson Belvedere Jazz Festival Tony Bennett Bergamo Jazz 1998 Berkley Jazz Festival 1976, 1984 Berkshire Music Barn 1958 Berliner Jazztage 1968 Berliner Jazz Tage 1970 Bill Berry and the L.A. Band Big Band Sounds 1942 Big Broadcast 1944 The Big Rhythm and Blues Show Oberlin Conservatory Library l 77 West College Street l Oberlin, Ohio 44074 l [email protected] l 440.775.5129 Oberlin Conservatory Library Special Collections James R. and Susan Neumann Jazz Collection Series 3: Concert Programs, 1942-2009 and undated P a g e | 2 The Big Show 1957, 1965 The Biggest Show of… 1951-1954 Birdland 1956 Birdland Stars of… 1955-1957 Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers Blue Note Boston Globe Jazz Festival Boston Jazz Festival Lester Bowie British Jazz Extravaganza Big Bill Broonzy Les Brown and His Band of Renown -

Trad Jazz in 1950S Britain—Protest, Pleasure, Politics— Interviews with Some of Those Involved

Trad jazz in 1950s Britain—protest, pleasure, politics— interviews with some of those involved George McKay These are transcriptions of interviews and correspondence undertaken as part of an Arts and Humanities Research Board (now Council)-funded project exploring the cultures and politics of traditional jazz in Britain in the 1950s. The project ran through 2001-2002 and was entitled American Pleasures, Anti- American Protest: 1950s Traditional Jazz in Britain. I edited responses, and structured them here according to the main issues I asked about and to key points that seemed to recur from different interviewees. There is a short-ish introduction to give a sense of context to readers unfamiliar with that period of Britain’s cultural history. I hugely enjoyed meeting and talking with these people, whose cultural and political autobiographies were full of energy, rebellion, fun, with music at the heart. Thank you. Some—Jeff Nuttall, George Melly—are, sadly, now dead. Material from these interviews, and a second set I undertook with modern jazzers and enthusiasts (I acknowledge that the distinction between trad and modern doesn’t always bear scrutiny) was included in my book Circular Breathing: The Cultural Politics of Jazz in Britain (Duke University Press, 2005). Do contact me if you have any queries. George McKay University of Salford, UK [email protected] April 2002; revised (with extra images) September 2002; revised introduction January 2010 (little has change except the point that I now know that the David Boulton jazz historian and the David Boulton of CND were one and the same person) Most of the archive photographs here are either from Jeff Nuttall’s photo album, which he gave me at the end of our interview in Abergavenny—I’d like to pass it on to a family member, please—or © and courtesy of the Ken Colyer Trust: www.kencolyertrust.org 1 Introduction British jazz has arrived, in Britain at any rate. -

Felix Issue 0001, 1988 Additional/Special Issue

FREE! No. 803 Friday 20th May 1988 INSIDE Bridge in troubled water Students are still in the dark over the suspension of the Union Snack emergency motion, proposed by 4 Union and Bar staff and over the position of Deputy President Alan Rose, Chris Martin and opposed by the ICU President, concerned the position of following yesterday's AGM. The Union Executive gave a limited ,the Deputy President, Mr Alan Rose, Letter from explanation of the crisis, but were not able to disclose full details. who has been relieved of his The meeting was opened to an this year's ICU Honorary Secretary, management responsibility for the St Mary's audience of around 200 students at for his work as last year's ICU trading outlets. The motion called on 1.05pm yesterday in the Union Publicity Officer and Hon Sec. the Executive to explain why they Concert Hall. It was decided that Quentin Fontana was also given a took the action regarding Mr Rose 5 Libel and awards should be handed out to their UGA for his work as ICU Honorary and to present any evidence they had various recipients before the rest of Secretary two years ago. Mr Fontana regarding his alledged 'gross Blackmail the business was dealt with. is no longer a student at Imperial and misconduct'. It also called for an open The first awards to be made were was not awarded a UGA by Carl debate on the matter. After speeches ICU Social Colours to members of Burgess, the ICU President two years from both sides, the motion was Science College staff. -

STONY BROOK PLAYERS - JI I I __ L1 L 1- PRESENT KEI LLY A'sng

I Thurs. Apr. 5,1984II VoLV. No. 22@ Universityl........i.....i.ii........... Community's................. Weekly ii..................................... Paper* .... ...... -..-.-....................................................................... .............. Electioneering Begins Presidential Hopefuls Begin Campaigns by Joe Caponi going for the top spot. Two candidates accessible to people, it's much too cen- The 1984 Polity election campaign have already begun campaigning in tralized up there in the Union Office. has begun with a burst of activity earnest. We have to bring in some new perspec- .. unheard of in recent years as a number Polity Secretary Belina Anderson tive." About her own experience in of candidates prepare to fight for the says that she plans to stress two major Polity, Anderson said, "Having seen .. Presidency. themes in her campaign for the Presi- just how Polity has failed in the past, The election is scheduled for dency. "The Polity structure needs a you can see much more clearly how to Thursday, April 26, and petitioning major overhaul. The Senate and Judi- make it better." opens today for all available seats. ciary have to function the way that they Saying "Polity has become in- SCandidates will have a week to corn- were designed to and that depends alot creasingly less effective in being re- plete their petitions to be placed on the on the P resident and the Council giving sponsive to student needs and I think ballot. them and the other people in Polity a that it's time to change that," junior What will make this campaign dif- clear idea of what their functions are Danny Wexler explained his entry into ferent from previous ones is in the and how they can accomplish them.