Rapid Sequence Induction (RSI) for Endotracheal Intubation February 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ISPUB - Dilemma in Rapid Sequence Intubation: Succinylcholi

ISPUB - Dilemma In Rapid Sequence Intubation: Succinylcholi... http://www.ispub.com/journal/the_internet_journal_of_emerge... The Internet Journal of Emergency and Intensive Care Medicine 2003 : Volume 7 Number 1 Dilemma In Rapid Sequence Intubation: Succinylcholine Vs. Rocuronium Ozgur Karcioglu MD Emergency Physician Dept. of Emergency Medicine Dokuz Eylul Univ. School of Medicine Izmir Turkey Citation: O. Karcioglu : Dilemma In Rapid Sequence Intubation: Succinylcholine Vs. Rocuronium . The Internet Journal of Emergency and Intensive Care Medicine. 2003 Volume 7 Number 1 Keywords: Rapid sequence intubation | rapid sequence induction | neuromuscular blockade | muscle paralysis | succinylcholine | rocuronium Abstract Succinylcholine is the single ultra-short acting depolarizing neuromuscular blocking agent (NMBA) used in the rapid sequence intubation protocol with 1 of 14 9/8/10 11:29 PM ISPUB - Dilemma In Rapid Sequence Intubation: Succinylcholi... http://www.ispub.com/journal/the_internet_journal_of_emerge... its rapid onset of effect, complete reliability, short duration of action. Rocuronium is diverse from other non-depolarizing NMBA being the first one with a short onset time and devoid of untoward effects. Despite its widespread use, succinylcholine has several potential hazards including an increase in potassium levels, bradycardia for children and prolonged apnea for those with pseudocholinesterase deficiency. Rocuronium is indicated in subjects with disease states such as known or suspected hyperkalemia, crush injury, non-acute burns, increased intracranial or intraocular pressure and neuromuscular disease. Although succinylcholine has many side effects, it remains to be the first-choice NMBA for the majority of attempts for rapid sequence intubation. Rocuronium may be a suitable alternative to succinylcholine with its short onset time. The objective of this article is to update data from studies comparing the use of succinylcholine and rocuronium in rapid sequence intubation protocol in adults. -

Rapid Sequence Induction Will Ross and Louise Ellard

Update in Anaesthesia Rapid sequence induction Will Ross and Louise Ellard Correspondence: [email protected] Originally published as Anaesthesia Tutorial of the Week 331, 24 May 2016, edited by Dr Luke Baitch Table 1. Common modifications of RSI technique in INTRODUCTION current practice Rapid sequence induction (RSI) is a method of achiev- Omitting the placement of an oesophageal tube articlesClinical overview ing rapid control of the airway whilst minimising Supine or ramped positioning the risk of regurgitation and aspiration of gastric Titrating the dose of induction agent to loss of contents. Intravenous induction of anaesthesia, with consciousness the application of cricoid pressure, is swiftly followed Summary by the placement of an endotracheal tube (ETT). Use of propofol, ketamine, midazolam or etomidate to Rapid sequence induction induce anaesthesia (RSI) is intended to reduce Performance of an RSI is a high priority in many the risk of aspiration by emergency situations when the airway is at risk, and Use of high-dose rocuronium as a neuromuscular blocking agent minimising the duration is usually an essential component of anaesthesia for of an unprotected airway. Omitting cricoid pressure emergency surgical interventions. RSI is required only Preparation and planning in patients with preserved airway reflexes. In arrested – including technique, or completely obtunded patients, an endotracheal tube medications, team member can usually be placed without the use of medications. CRICOID PRESSURE roles and contingencies -

Significant Modification of Traditional Rapid Sequence Induction Improves Safety and Effectiveness of Pre-Hospital Trauma Anaesthesia Lyon Et Al

Significant modification of traditional rapid sequence induction improves safety and effectiveness of pre-hospital trauma anaesthesia Lyon et al. Lyon et al. Critical Care (2015) 19:134 DOI 10.1186/s13054-015-0872-2 Lyon et al. Critical Care (2015) 19:134 DOI 10.1186/s13054-015-0872-2 RESEARCH Open Access Significant modification of traditional rapid sequence induction improves safety and effectiveness of pre-hospital trauma anaesthesia Richard M Lyon1†, Zane B Perkins1,3*†, Debamoy Chatterjee1, David J Lockey2, Malcolm Q Russell1 and on behalf of Kent, Surrey & Sussex Air Ambulance Trust Abstract Introduction: Rapid Sequence Induction of anaesthesia (RSI) is the recommended method to facilitate emergency tracheal intubation in trauma patients. In emergency situations, a simple and standardised RSI protocol may improve the safety and effectiveness of the procedure. A crucial component of developing a standardised protocol is the selection of induction agents. The aim of this study is to compare the safety and effectiveness of a traditional RSI protocol using etomidate and suxamethonium with a modified RSI protocol using fentanyl, ketamine and rocuronium. Methods: We performed a comparative cohort study of major trauma patients undergoing pre-hospital RSI by a physician-led Helicopter Emergency Medical Service. Group 1 underwent RSI using etomidate and suxamethonium and Group 2 underwent RSI using fentanyl, ketamine and rocuronium. Apart from the induction agents, the RSI protocol was identical in both groups. Outcomes measured included laryngoscopy view, intubation success, haemodynamic response to laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation, and mortality. Results: Compared to Group 1 (n = 116), Group 2 RSI (n = 145) produced significantly better laryngoscopy views (p = 0.013) and resulted in significantly higher first-pass intubation success (95% versus 100%; p = 0.007). -

Rsii Rapid-Sequence Induction of Anaesthesia and Intubation of the Trachea

Disaster and Emergency Medicine Journal 2017, Vol. 2, No. 1, 33–38 REVIEW ARTICLE DOI: 10.5603/DEMJ.2017.0006 Copyright © 2017 Via Medica ISSN 2451–4691 RSII RAPID-SEQUENCE INDUCTION OF ANAESTHESIA AND INTUBATION OF THE TRACHEA Bogumila Woloszczuk-Gebicka Department of Intensive Care and Toxicology, Chair of Rescue Medicine, Institute of Midwifery and Rescue Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Rzeszów ABSTRACT Rapid sequence induction and intubation (RSII) is the preferred method of tracheal intubation in emergen- cy situations for patients presenting with a full stomach. The aim of RSII is to intubate the trachea within 60 seconds, without having to use bag-valve-mask ventilation to avoid air insufflation into the stomach. After preoxygenation and while cricoid pressure is applied, an induction dose of intravenous anaesthetic agent is administered and rapidly followed by a fast-acting muscle relaxant, and after 60 seconds tracheal intubation is performed. Preoxygention increases apnoea tolerance. This is particularly important for infants and young children, and in patients who are in critical condition, obese or pregnant. Cricoid pressure (the Sellick manouver) is recommended to prevent regurgitation of the gastric contents to the throat. Propofol or thiopental are routinely used for induction. Ketamine or etomidate may be used if propofol or thiopental administration is contraindicated. Succinylcholine or rocuronium are used to facilitate tracheal intubation. Poor jaw relaxation, patient resistance to a laryngoscope, closed or closing vocal cords, vigorous limb movements or sustained coughing after tube insertion are not clinically acceptable. Modified rapid sequence induction, used in patients at risk of rapid development of hypoxaemia, allows gentle positive pressure ventilation after administration of the induction agent and muscle relaxant, but before the tracheal intubation. -

Rapid Sequence Intubation

Challenges and Advances in Intubation: Rapid Sequence Intubation a,b,c,d, Sharon Elizabeth Mace, MD, FACEP, FAAP * KEYWORDS Intubation Rapid sequence intubation Endotracheal intubation DEFINITION/OVERVIEW Rapid sequence intubation (RSI) is a process whereby pharmacologic agents, specif- ically a sedative (eg, induction agent) and a neuromuscular blocking agent are admin- istered in rapid succession to facilitate endotracheal intubation.1 RSI in the emergency department (ED) usually is conducted under less than optimal conditions and should be differentiated from rapid sequence induction (also often ab- breviated RSI) as practiced by anesthesiologists in a more controlled environment in the operating room to induce anesthesia in patients requiring intubation.2–6 RSI used to secure a definitive airway in the ED frequently involves uncooperative, nonfasted, unstable, critically ill patients. In anesthesia, the goal of rapid sequence induction is to induce anesthesia while using a rapid sequence approach to decrease the possibil- ity of aspiration. With emergency RSI, the goal is to facilitate intubation with the addi- tional benefit of decreasing the risk of aspiration. Although there are no randomized, controlled trials documenting the benefits of RSI,7 and there is controversy regarding various steps in RSI in adult and pediatric pa- tients,8–13 RSI has become standard of care in emergency medicine airway manage- ment14–17 and has been advocated in the airway management of intensive care unit or critically ill patients.18 RSI has also -

Alternatives to Rapid Sequence Intubation: Contemporary Airway Management with Ketamine

REVIEW ARTICLE Alternatives to Rapid Sequence Intubation: Contemporary Airway Management with Ketamine Andrew H. Merelman, BS* *Rocky Vista University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Parker, Colorado Michael C. Perlmutter, BA†‡ †University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, Minnesota Reuben J. Strayer, MD§ ‡North Memorial Health Ambulance and AirCare, Brooklyn Center, Minnesota §Maimonides Medical Center, Department of Emergency Medicine, Brooklyn, New York Section Editor: Christopher R. Tainter, MD Submission history: Submitted February 14, 2019; Revision received April 8, 2019; Accepted April 6, 2019 Electronically published April 26, 2019 Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem DOI: 10.5811/westjem.2019.4.42753 Endotracheal intubation (ETI) is a high-risk procedure commonly performed in emergency medicine, critical care, and the prehospital setting. Traditional rapid sequence intubation (RSI), the simultaneous administration of an induction agent and muscle relaxant, is more likely to harm patients who do not allow appropriate preparation and preoxygenation, have concerning airway anatomy, or severe hypoxia, acidemia, or hypotension. Ketamine, a dissociative anesthetic, can be used to facilitate two alternatives to RSI to augment airway safety in these scenarios: delayed sequence intubation – the use of ketamine to allow airway preparation and preoxygenation in the agitated patient; and ketamine-only breathing intubation, in which ketamine is used without a paralytic to facilitate ETI as the patient continues to breathe spontaneously. Ketamine may also provide hemodynamic benefits during standard RSI and is a valuable agent for post-intubation analgesia and sedation. When RSI is not an optimal airway management strategy, ketamine’s unique pharmacology can be harnessed to facilitate alternative approaches that may increase patient safety. -

Rapid Sequence Induction: Evidence Based Review

Andrew Triebwasser Department of Anesthesiology Hasbro Children’s Hospital NOVEMBER 2011 identify “full-stomach” patients at risk for aspiration of gastric contents describe rationale for use of rapid-sequence induction (RSI) in full-stomach patients explain the historical context of cricoid pressure and current evidence for its efficacy despite near “standard of care” status, there are numerous variations in the technique of RSI, first described approximately 40 years ago these include: choice and timing of NMB, use of positive-pressure ventilation, patient position BUT the application and use of cricoid pressure is the most controversial aspect of modern RSI, and will be the focus of this review Berlin Wall goes up; Bay of Pigs disaster Yuri Gagarin (not Alan Shepard) first in space song – “Will You Love me Tomorrow?” movies – “West Side Story” & “The Hustler” TV – “Bonanza”, debut of “Mr. Ed” first electric toothbrush; IBM Selectric golfball average: car $2850; home $12,500 gasoline 27¢ a gallon; eggs 30¢ a dozen aspiration a feared complication of anesthesia 1940 -15 cases in obstetrics (Hall) 1946 – comprehensive review (Mendelson)* • mechanical obstruction vs. “late” pneumonitis • impact gastric volume & acidity, airway mgmt • Mendelson’s Syndrome: ↑ risk gastric contents 0.4 ml/kg & pH < 2.5 (unpublished data 1974) 1951- 2% of all maternal deaths (Merrill)** 1956 – 19% anesthetic deaths (Edwards)*** *Amer J Obstet Gynec 52:191;1946 **Curr Res Anesth Analg 1951;30:121 ***Anaesthesia1956;11:194 esophageal pathology – obstruction, pouch, smooth muscle disorders (scleroderma) gastric ingestion (food, swallowed blood) delayed gastric emptying ◦ obstruction, pain, opioids, belladonna alkaloids elevation of intragastric pressure ◦ sux, airway management, patient positioning Salem MR. -

RSI and Intubation

Category Clinical Practice Protocol: BICU Rapid Sequence Induction and Intubation Approval Date: 5/28/2020 (CMT) Review Date: 6/1/2022 Applicable to ☒ VUH ☒ VCH ☐ DOT ☐ VMG Off-site locations ☐ VMG ☐ VPH ☐ Other Team Members Performing ☐ All faculty & ☒ Faculty & staff ☒ MD ☒ House Staff ☒ APRN/PA ☐ RN ☐ LPN staff providing direct patient care or ☐ Other: contact Content Experts Author: Roy Neely, MD Assistant Professor, Anesthesia Critical Care Table of Contents I. Goal II. Indication III. Contraindications IV. Medications V. Equipment VI. Personnel and Procedure VII. Background VIII. References BICU RSI I. Goal To induce unconsciousness and paralysis to facilitate rapid tracheal intubation II. Indication Rapid sequence induction and intubation (RSII) is a technique commonly used to secure the airway quickly and protect against aspiration of gastric contents. • When residual stomach content is expected o Oral intake within 6 hours o Delayed gastric emptying due to gastroparesis, diabetes mellitus, medications (opioids) and/or trauma o Gastrointestinal obstruction, e.g. ileus, pyloric or small bowel obstruction, colonic obstruction, large upper GI bleeding • Other indications o Severe hypoxia requiring immediate intubation and mechanical ventilation o Imminent (as in looming) airway obstruction, e.g. facial burn and/or progressive stridor III. Contraindications Anticipation of a difficult airway, especially if rescue oxygenation may be difficult or impossible IV. Medications • Premedications o Preoxygenation- 100% NRB, bag-assisted ventilation ▪ If time allows: Fentanyl (1 to 3 μg/kg), fast and short acting narcotic, decreases induction agent requirement, improves hemodynamic stability and blunts airway reflexes to intubation ▪ Midazolam (1-2mg): fast acting anxiolytic may facilitate preparation for RSI ▪ Atropine (0.01 mg/kg): helpful with patients with bradycardia or with anticipated bradycardia after induction of anesthesia. -

Predictors of the Complication of Postintubation Hypotension During Emergency Airway Management☆ Alan C

Journal of Critical Care (2012) 27, 587–593 Predictors of the complication of postintubation hypotension during emergency airway management☆ Alan C. Heffner MD a,b,⁎, Douglas S. Swords BA, MS IV b, Marcy L. Nussbaum MS c, Jeffrey A. Kline MD b, Alan E. Jones MD b,d aDivision of Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Charlotte, NC bDepartment of Emergency Medicine, Carolinas Medical Center, Charlotte, NC cDickson Institute for Health Studies, Carolinas HealthCare System, Charlotte, NC dDepartment of Emergency Medicine, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS Keywords: Abstract Intubation; Objective: Arterial hypotension is a recognized complication of emergency intubation that is Complication; independently associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Our aim was to identify factors Hypotension; associated with postintubation hypotension after emergency intubation. Post-intubation Methods: Retrospective cohort study of tracheal intubations performed in a large, urban emergency hypotension; department over a 1-year period. Patients were included if they were older than 17 years and had no Shock index systolic blood pressure measurements below 90 mm Hg for 30 consecutive minutes before intubation. Patients were analyzed in 2 groups, those with postintubation hypotension (PIH), defined as any recorded systolic blood pressure less than 90 mm Hg within 60 minutes of intubation, and those with no PIH. Multiple logistic regression modeling was used to define predictors of PIH. Results: A total 465 patients underwent emergency intubation during the study period, and 300 met inclusion criteria for this study. Postintubation hypotension occurred in 66 (22%) of 300 patients, and these patients experienced significantly higher in-hospital mortality (35% vs 20%; odds ratio [OR] 2.1; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.2-3.9). -

Premedication During Rapid Sequence Intubation: a Necessity Or Waste of Valuable Time?

UC Irvine Western Journal of Emergency Medicine: Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health Title Premedication During Rapid Sequence Intubation: A Necessity or Waste of Valuable Time? Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9kw053xz Journal Western Journal of Emergency Medicine: Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health, 7(4) ISSN 1936-900X Author Schofer, Joel M Publication Date 2006 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The California Journal of Emergency Medicine VII:4, Dec. 2006 Page 75 Clinical Review PREMEDICATION DURING RAPID SEQUENCE INTUBATION: A Necessity or Waste of Valuable Time? Joel M. Schofer, MD Department of Emergency Medicine, Naval Medical Center San Diego Correspondence: Joel M. Schofer, MD, 628 Sand Shell Avenue, Carlsbad, California 92011. Tel: 69-459-256. Fax: 760-476-0722. Email: [email protected] INTRODUCTION Table . Physiologic responses increased by laryngos- Every day, thousands of patients who present to copy and intubation emergency departments (EDs) require tracheal intubation for _______________________________________________ optimal care. Most acute intubations are performed using • Blood pressure rapid sequence intubation (RSI), with the administration of • Pulse an intravenous sedative followed by a paralytic agent, to ob- • Cerebral oxygen demand tain the best chance for successful intubation. Premedication • Myocardial oxygen demand with various agents prior to RSI when certain conditions are • Cerebral blood flow present is recommended by experts in acute airway manage- • Intracranial pressure ment, as well as by many authors of major emergency medi- • Intraocular pressure cine textbooks and advanced airway instructional courses. • Laryngospasm This premedication is touted as a way to limit physiologic • Bronchospasm responses to intubation that may adversely affect the patient. -

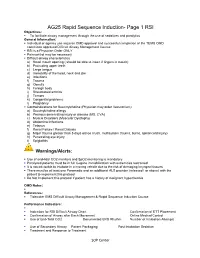

AG25 Rapid Sequence Induction- Page 1 RSI Objectives

AG25 Rapid Sequence Induction- Page 1 RSI Objectives: . To facilitate airway management through the use of sedatives and paralytics General Information: . Individual or agency use requires OMD approval and successful completion of the TEMS OMD committee approved Difficult Airway Management Course . RSI is a Physician Order ONLY . Pain control may be necessary . Difficult airway characteristics a) Small mouth opening ( should be able to insert 2 fingers in mouth) b) Protruding upper teeth c) Large tongue d) Immobility of the head, neck and jaw e) Infections f) Trauma g) Obesity h) Foreign body i) Rheumatoid arthritis j) Tumors k) Congenital problems l) Pregnancy . Contraindications for Succinylcholine (Physician may order Vecuronium): a) Succinylcholine allergy b) Previous denervating injury or disease (MS, CVA) c) Muscle Disorders (Muscular Dystrophy) d) Abdominal Infections e) Tetanus f) Renal Failure / Renal Dialysis g) Major trauma greater than 5 days old (ie crush, multisystem trauma, burns, spinal cord injury) h) Penetrating eye injury i) Epiglottitis Warnings/Alerts: . Use of end-tidal CO2 monitors and SpO2 monitoring is mandatory . Paralyzed patients must be in full C-spine immobilization with extremities restrained . It is not advisable to intubate in a moving vehicle due to the risk of damaging laryngeal tissues . There must be at least one Paramedic and an additional ALS provider (released I or above) with the patient to implement this protocol . Do Not Implement this protocol if patient has a history of malignant hyperthermia OMD Notes: . References: . Tidewater EMS Difficult Airway Management & Rapid Sequence Induction Course Performance Indicators: . Indication for RSI Difficult Airway Chart Confirmation of ETT Placement . -

Trauma Airway Management

The Journal of Emergency Medicine, Vol. 46, No. 6, pp. 814–820, 2014 Copyright Ó 2014 Elsevier Inc. Printed in the USA. All rights reserved 0736-4679/$ - see front matter http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.11.085 Trauma Reports TRAUMA AIRWAY MANAGEMENT Cheryl Lynn Horton, MD, Calvin A. Brown III, MD, and Ali S. Raja, MD, MBA, MPH Department of Emergency Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts Reprint Address: Ali S. Raja, MD, MBA, MPH, Department of Emergency Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital75 Francis Street, Neville House 312E, Boston, MA 02115 , Abstract—Background: Airway management in a saturation of 97% on room air. He had sustained obvious trauma patient can be particularly challenging when both head, face, and chest injuries. He was placed in a cervical a difficult airway and the need for rapid action collide. collar, extricated, and brought to the ED on a backboard. The provider must evaluate the trauma patient for airway Immediately upon arrival to the ED, his primary sur- difficulty, develop an airway management plan, and be vey was notable for incoherent speech and a hoarse voice. willing to act quickly with incomplete information. Discus- He had decreased breath sounds on the right, 2+ symmet- sion: Thorough knowledge of airway management algo- rithms will assist the emergency physician in providing ric pulses throughout, and visible right chest wall ecchy- optimal care and offer a rapid and effective treatment mosis. His initial ED vitals signs revealed a blood plan. Conclusions: Using a case-based approach, this article pressure of 95/70 mm Hg, a pulse of 115 bpm, a temper- reviews initial trauma airway management strategies along ature of 37.2 C, and an oxygen saturation of 96% on with the rationale for evidence-based treatments.