The Status of the California Least Tern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEAST TERN Scientific Name: Sternula Antillarum Lesson Other

Common Name: LEAST TERN Scientific Name: Sternula antillarum Lesson Other Commonly Used Names: Little tern, silver turnlet, sea swallow, minute tern, little striker, and killing peter Previously Used Names: Sterna antillarum Family: Laridae Rarity Ranks: G4/S3 State Legal Status: Rare Federal Legal Status: Interior population listed as endangered. Other populations are not federally listed. Federal Wetland Status: N/A Description: Georgia's smallest tern at about 23 cm (9 in) in length with a 50 cm (20 in) wingspread, the least tern is white with pale gray feathers on the back and upper surfaces of the wings, except for a narrow black stripe along the leading edge of the upper wing feathers. The least tern has a black cap with a small patch of white on the forehead. In summer, the adult has a yellow bill with a black tip and yellow to orange feet and legs. Its tail is deeply forked. In winter, the bill, legs and feet are black. The juvenile has a black bill and yellow legs, and the feathers of the back have dark margins, giving the bird a distinctly "scaled" appearance. The least tern's small size, white forehead, and yellow bill serve to distinguish it from other terns. Similar Species: The adult sandwich tern (Thalasseus sandvicensis) is the most similar species to the adult least tern, but is much larger at about 38 cm (15 in) in length and has a black bill with a pale (usually yellow) tip and black legs. Juvenile least terns and sandwich terns look very similar in appearance. -

Magnolia Plantation and Gardens Birdwalk Newsletter 5.7.2017 Walks Conducted by Perry Nugent Articles Written by Jayne J Matney All Owl Photos by Guenter Weber

Magnolia Plantation and Gardens BirdWalk Newsletter 5.7.2017 Walks Conducted by Perry Nugent Articles Written by Jayne J Matney All Owl Photos By Guenter Weber “The owl,” he was saying, “is one of the most curious creatures. A bird that stays awake when the rest of the world sleeps. They can see in the dark. I find that so interesting, to be mired in reality when the rest of the world is dreaming. What does he see and what does he know that the rest of the world is missing?” M.J. Rose Barred Owls: Strix varia Owls capture our curiosity at an early age because of their unique characteristics and the mystery that seems to surround them. Being mostly nocturnal and highly camouflaged, sighting an owl in the day is fairly rare and is very exciting when it happens. Owls in general range in sizes and coloration. Here on our plantation, especially during mating and nesting season, sightings are made and amazing photos have been turned in for our pleasure. The Barred Owl sightings and photos have been the inspiration for the article this week. Barred Owls are large owls (40 to 64 cm long or 16 to 26 inches), native to eastern United States, and named after their distinct bar coloration on their feathers of the chest and belly. The bars on the chest are horizontal, while the bars on the belly are vertical. The rest of the body is mostly a mottled gray-brown. They possess a pale face with dark rings radiating about the eyes, and incredible dark brown eyes unlike other owls that have yellow eyes. -

Predator and Competitor Management Plan for Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge

Appendix J /USFWS Malcolm Grant 2011 Fencing exclosure to protect shorebirds from predators Predator and Competitor Management Plan for Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge Background and Introduction Background and Introduction Throughout North America, the presence of a single mammalian predator (e.g., coyote, skunk, and raccoon) or avian predator (e.g., great horned owl, black-crowned night-heron) at a nesting site can result in adult bird mortality, decrease or prevent reproductive success of nesting birds, or cause birds to abandon a nesting site entirely (Butchko and Small 1992, Kress and Hall 2004, Hall and Kress 2008, Nisbet and Welton 1984, USDA 2011). Depredation events and competition with other species for nesting space in one year can also limit the distribution and abundance of breeding birds in following years (USDA 2011, Nisbet 1975). Predator and competitor management on Monomoy refuge is essential to promoting and protecting rare and endangered beach nesting birds at this site, and has been incorporated into annual management plans for several decades. In 2000, the Service extended the Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge Nesting Season Operating Procedure, Monitoring Protocols, and Competitor/Predator Management Plan, 1998-2000, which was expiring, with the intent to revise and update the plan as part of the CCP process. This appendix fulfills that intent. As presented in chapter 3, all proposed alternatives include an active and adaptive predator and competitor management program, but our preferred alternative is most inclusive and will provide the greatest level of protection and benefit for all species of conservation concern. The option to discontinue the management program was considered but eliminated due to the affirmative responsibility the Service has to protect federally listed threatened and endangered species and migratory birds. -

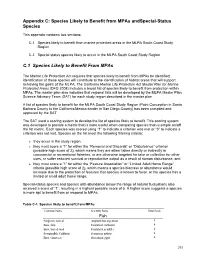

List of Species Likely to Benefit from Marine Protected Areas in The

Appendix C: Species Likely to Benefit from MPAs andSpecial-Status Species This appendix contains two sections: C.1 Species likely to benefit from marine protected areas in the MLPA South Coast Study Region C.2 Special status species likely to occur in the MLPA South Coast Study Region C.1 Species Likely to Benefit From MPAs The Marine Life Protection Act requires that species likely to benefit from MPAs be identified; identification of these species will contribute to the identification of habitat areas that will support achieving the goals of the MLPA. The California Marine Life Protection Act Master Plan for Marine Protected Areas (DFG 2008) includes a broad list of species likely to benefit from protection within MPAs. The master plan also indicates that regional lists will be developed by the MLPA Master Plan Science Advisory Team (SAT) for each study region described in the master plan. A list of species likely to benefit for the MLPA South Coast Study Region (Point Conception in Santa Barbara County to the California/Mexico border in San Diego County) has been compiled and approved by the SAT. The SAT used a scoring system to develop the list of species likely to benefit. This scoring system was developed to provide a metric that is more useful when comparing species than a simple on/off the list metric. Each species was scored using “1” to indicate a criterion was met or “0” to indicate a criterion was not met. Species on the list meet the following filtering criteria: they occur in the study region, they must score a “1” for either -

Inventory of Terns, Laughing Gulls, and Black Skimmers Nesting in Massachusetts in 2010

INVENTORY OF TERNS, LAUGHING GULLS, AND BLACK SKIMMERS NESTING IN MASSACHUSETTS IN 2010 Juvenile Roseate Tern, Massachusetts. Prepared by: Carolyn S. Mostello Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program Rte. 135, Westborough, MA 01581 August 2011 Abstract Cooperators in Massachusetts surveyed more than 141 coastal sites in 2010 for the presence of breeding Roseate Terns (Sterna dougallii), Common Terns (Sterna hirundo), Arctic Terns (Sterna paradisaea), Least Terns (Sternula antillarum), Laughing Gulls (Larus atricilla), and Black Skimmers (Rhynchops niger). Eighty sites were occupied by nesting birds of one or more of these species. Roseate Terns increased 4.0% to 1,393 pairs. Common Terns and Least Terns were stable at 16,224 and 3,484 pairs, respectively. Laughing Gulls decreased 23.3% to 1,249 pairs. Five pairs of Black Skimmers nested during the peak of the season and three pairs nested late. Two-and-a-half pairs of Arctic Terns nested during the peak. Introduction Coastal waterbirds are a vulnerable group of species. Of Massachusetts’ four nesting tern species, the Common Tern, the Least Tern and the Arctic Tern are listed as “Special Concern” pursuant to the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act. The Roseate Tern is listed as “Endangered” pursuant to both the Massachusetts and U.S. Endangered Species Acts. Terns, Laughing Gulls, and Black Skimmers in Massachusetts are protected and monitored by an extensive network of cooperators throughout the state. These cooperators provide census data and other reproductive information to the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife (MDFW). This allows wildlife managers to determine abundance and status of, and threats to, these species. -

Watershed Summaries

Appendix A: Watershed Summaries Preface California’s watersheds supply water for drinking, recreation, industry, and farming and at the same time provide critical habitat for a wide variety of animal species. Conceptually, a watershed is any sloping surface that sheds water, such as a creek, lake, slough or estuary. In southern California, rapid population growth in watersheds has led to increased conflict between human users of natural resources, dramatic loss of native diversity, and a general decline in the health of ecosystems. California ranks second in the country in the number of listed endangered and threatened aquatic species. This Appendix is a “working” database that can be supplemented in the future. It provides a brief overview of information on the major hydrological units of the South Coast, and draws from the following primary sources: • The California Rivers Assessment (CARA) database (http://www.ice.ucdavis.edu/newcara) provides information on large-scale watershed and river basin statistics; • Information on the creeks and watersheds for the ESU of the endangered southern steelhead trout from the National Marine Fisheries Service (http://swr.ucsd.edu/hcd/SoCalDistrib.htm); • Watershed Plans from the Regional Water Quality Control Boards (RWQCB) that provide summaries of existing hydrological units for each subregion of the south coast (http://www.swrcb.ca.gov/rwqcbs/index.html); • General information on the ecology of the rivers and watersheds of the south coast described in California’s Rivers and Streams: Working -

California Least Tern (Sternula Antillarum Browni)

California least tern (Sternula antillarum browni) 5-Year Review Summary and Evaluation u.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Carlsbad Fish and Wildlife Office Carlsbad, California September 2006 5-YEARREVIEW California least tern (Sternula antillarum browni) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. GENERAL INFORMATION 1 1.1. REVIEWERS 1 1.2. METHODOLOGY USED TO COMPLETE THE REVIEW: 1 1.3. BACKGROUND: 1 2. REVIEW ANALYSIS 2 2.1. ApPLICATION OF THE 1996 DISTINCT POPULATION SEGMENT (DPS) POLICY 2 2.2. RECOVERY CRITERIA 2 2.3. UPDATED INFORMATION AND CURRENT SPECIES STATUS 5 2.4. SyNTHESIS 22 3. RESULTS 22 3.1. RECOMMENDED CLASSIFICATION 22 3.2. NEW RECOVERY PRIORITY NUMBER 22 3.3. LISTING AND RECLASSIFICATION PRIORITY NUMBER, IF RECLASSIFICATION IS RECOMMENDED 23 4.0 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE ACTIONS 23 5.0 REFERENCES •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 24 11 5-YEAR REVIEW California least tern (Sternula antillarum browni) 1. GENERAL INFORMATION 1.1. Reviewers Lead Region: Diane Elam and Mary Grim, California-Nevada Operations Office, 916- 414-6464 Lead Field Office: Jim A. Bartel, Carlsbad Fish and Wildlife Service, 760-431-9440 1.2. Metnodoiogy used to complete the review: This review was compiled by staffofthe Carlsbad Fish and Wildlife Office (CFWO). The review was completed using documents from office files as well as available literature on the California least tern. 1.3. Background: 1.3.1. FR Notice citation announcing initiation of this review: The notice announcing the initiation ofthis 5-year review and opening ofthe first comment period for 60 days was published on July 7, 2005 (70 FR 39327). A notice reopening the comment period for 60 days was published on November 3, 2005 (70 FR 66842). -

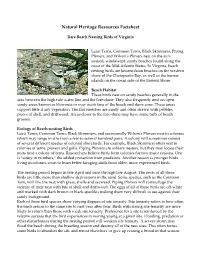

Beach Nesting Bird Colonies

Natural Heritage Resources Factsheet Rare Beach Nesting Birds of Virginia Least Terns, Common Terns, Black Skimmers, Piping Plovers, and Wilson's Plovers nest on the sun- soaked, windswept, sandy beaches found along the coast of the Mid-Atlantic States. In Virginia, beach nesting birds are known from beaches on the western shore of the Chesapeake Bay, as well as the barrier islands on the ocean side of the Eastern Shore. Beach Habitat These birds nest on sandy beaches generally in the area between the high tide water line and the fore-dune. They also frequently nest on open sandy areas known as blowouts or over wash fans of the beach and dune zone. These areas support little if any vegetation. The flat stretches are sandy and often strewn with pebbles, pieces of shell, and driftwood. Areas closer to the fore-dune may have some tufts of beach grasses. Ecology of Beach-nesting Birds Least Terns, Common Terns, Black Skimmers, and occasionally Wilson's Plovers nest in colonies which may range in size from a few to several hundred pairs. A colony will sometimes consist of several different species of colonial shorebirds. For example, Black Skimmers often nest in colonies of terns, plovers and gulls. Piping Plovers are solitary nesters, but they may locate their nests near a colony of terns. Researchers believe birds form colonies for two major reasons. One is "safety in numbers," the added protection from predators. Another reason is younger birds living in colonies seem to learn better foraging skills from older, more experienced birds. The nesting period begins in late April and runs through late August. -

FINAL REPORT Foraging Study Least Terns 2009 No Appendices

FORAGING STUDY of California Least Terns in San Diego Bay 2009 Prepared for Naval Base Coronado under Cooperative Agreement # N62473-08-2-0027 with Naval Facilities Engineering Command Southwest San Diego, California by Patricia Baird, Ph.D. Kahiltna Research Group Simon Fraser University Centre for Wildlife Ecology Burnaby, B.C. Citation: Baird, Patricia. 2010. Foraging study of California Least Terns in San Diego Bay and Near Ocean Waters, San Diego, California. Unpublished Rept. U.S. NAVFACENGCOM, San Diego Part 1 Foraging Study of California Least Terns in San Diego Bay and Near ocean Waters Appendix I Detailed Methods and Data Sheets Appendix II Banding Data submitted to the U.S. Geological Survey Patricia Baird, Ph.D. Part 2 Analysis of Fecal Samples of California Least Terns Collected on U.S. Navy Least Tern Colonies, San Diego Bay 2008 Appendix III Detailed Methods and Data Sheets Daniel J. Pondella, II, MA, Ph.D. and Jonathan P. Williams, MS. Part 3 Summary and Analysis of Past Fish Collection Data, with Comparison to past Tern Productivity, San Diego Bay Appendix IV Detailed Methods and Data Sheets Daniel J. Pondella, II, MA, Ph.D. and Jonathan P. Williams, MS. Project managed by Friends of Colorado Lagoon 1 Part I FORAGING STUDY of CALIFORNIA LEAST TERNS IN SAN DIEGO BAY AND NEAR OCEAN WATERS SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA, 2009 FINAL REPORT Patricia Baird, Ph.D. Kahiltna Research Group Centre for Wildlife Ecology Simon Fraser University 125A-1030 Denman Street Vancouver, B.C. V6G 2M6 Canada Photo: Center for Biological Diversity Citation: Baird, P. 2010. Part 1. -

USFWS 1990 Least Tern Recovery Plan.Pdf

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR. U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE RECOVERY PLAN FOR THE INTERIOR POPULATION OF THE LEAST TERN (Sterna antillarum September i~~o Prepared by John G. Sidle U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service 203 West Second Street Grand Island, Nebraska 68801 and William F. Harrison U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Federal Building, Fort Snelling Twin Cities, Minnesota 55111 Regional Director ) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY OF THE RECOVERY PLAN FOR THE LEAST TERN CURRENT STATUS: The interior population of the least tern (Sterna antillarum), a breeding migratory bird in mid-America, was listed as endangered on June 27, 1985 (50 Federal Register 21,784-21,792). Census data currently indicate about 5,000 interior least terns. Habitat Reauirements and Limiting Factors: Interior least terns breed in the Mississippi and Rio Grande River Basins from Montana to Texas and from eastern New Mexico and Colorado to Indiana and Louisiana. From late April to August they occur primarily on barren to sparsely vegetated riverine sandbars, dike field sandbar islands, sand and gravel pits, and lake and reservoir shorelines. Threats to the survival of the species include the actual and functional loss of riverine sandbar habitat. Channelization and impoundment of rivers have directly eliminated nesting habitat. This recovery plan outlines recovery strategies to increase the interior population of the least tern to approximately 7,000 birds throughout its range. Recovery Objective: Delisting Recovery Criteria: Assure the protection of essential habitat by removal of current threats and habitat enhancement, establish agreed upon management plans, and attain a population of 7,000 birds at the levels listed below. -

Huntington State Beach

PARK FEES & REGULATIONS CONTINUED Sunset Warner Ave. Huntington Beach SANITATION STATION: Dumping gray or fresh water 405 39 on the ground is not allowed. An RV sanitation station State Beach Bolsa Chica is available for use. It is located in lot 2 just north of the 21601 Pacific Coast Highway State Beach 1 Brookhurst Kiosk. Huntington Beach, CA 92646 Huntington FIRE RINGS on the sand are available first-come, first- Beach served. Keep children away from fire rings, as they may (714) 536-1455 Beach Blvd. Pacific contain hot coals and ashes. Ocean Huntington Huntington State Beach is the site of a nesting sanctuary Santa Ana River Beach Pier Violation of the above regulations may result in a for the California least tern, a rare and endangered species. citation or your ejection from the park. The beach also provides sanctuary for the threatened Huntington Western snowy plover. The park features a bicycle trail, State Beach and surfing, skating and surf fishing are popular. to Crystal Cove State Beach (12 mi) FOLLOW BEACH SAFETY TIPS: • SWIM NEAR A LIFEGUARD. NEVER SWIM ALONE! PARK FEES & REGULATIONS • Check with lifeguards regarding ocean conditions DAY-USE FEES are due and payable upon entry into the before entering water. park. Please have your receipt visibly displayed in the • Swim in a lifeguard area only during duty hours. driver-side windshield of your vehicle. • Long-distance swimming is best done parallel DAY-USE hours are from 6 a.m. to 10 p.m. The multi-use to the shore. trail is a high-use area. Please keep personal belongings • Don’t panic if you are being pulled offshore by off trail and look both ways before crossing. -

Interior Least Tern in Dallas, Denton, and Tarrant Counties, Texas

The Endangered Interior Least Tern in Dallas, Denton, and Tarrant Counties, Texas The interior least tern (Sternula antillarum) Habitat was federally listed as endangered in 1985 (50 FR 21792) without critical habitat. Unlike Natural nesting habitat for the interior least most terns, it nests in the “interior” of the tern includes bare or sparsely vegetated salt United States, where it receives full protection flats, broad sandbars, and barren shores under the Endangered Species Act except along wide, shallow rivers and lakes. within 50 miles of the Gulf Coast. Historically, Favorable nesting habitat occurs along sand the tern nested on inland rivers from Texas to and gravel bars within wide unobstructed river Montana and from eastern Colorado and New channels, or open flats along shores of lakes Mexico to southern Indiana. Currently, the and reservoirs. Because natural nesting sites tern occurs in remnant colonies within the have become sparse, least terns have also historic distribution. Wintering occurs along adapted to using non-traditional nesting the Central American and northern South habitat within their range. Non-traditional American coasts. nesting habitat includes sand and gravel pits, dredge islands, dirt roads, and gravel Description rooftops. The interior least tern is the smallest North American tern, averaging 8 inches in length with a 20-inch wingspan. Breeding adults have a gray back, white undersurface, black- capped crown, white forehead, yellow bill with dark tip, and yellow to orange legs. Both male and female are alike. Immature birds have darker plumage than adults, a dark bill, and dark eye stripes on their white forehead. Terns arrive in Texas from late April to early June and spend 3 to 5 months at their breeding grounds.