RUSQ Vol. 57, No. 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abby Green Alex Kava Alex Kava Abbi Glines Abbi

Feuille1 Abbi Glines Abbi Glines Abbi Glines Abbi Glines Abbi Glines Abbi Glines Abbi Glines Abbi Glines Abbi Glines Abbi Glines Abbi Glines Abbi Glines Abbi Glines Abbi Glines Abbi Glines Abbi Glines Abbi Glines Abbi Glines Abby Green Adrianne Lee Alana Scott Alana Scott Alex Kava Alex Kava Page 1 Feuille1 Alex Kava Alex Kava Alex Kava Alex Kava Alex Kava Alex Kava Alex Kava Alex Kava Alex Kava Alex Kava Alexandra Ivy Alexandra Ivy Alexandra Ivy Alexandra Ivy Alexandra Ivy Alexandra Ivy Alexandra Ivy Alexandra Ivy Alexandra Ivy Alexandra Ivy Alexandra Ivy Alexandra Ivy Alexandra Ivy Alexandra Ivy Page 2 Feuille1 Alexandra Ivy Alexandra Ivy Alexandra Ivy Alexandra Ivy Alexandra Ivy Alexandra Sellers Alexandra Sellers Alexandra Sellers Alexandra Sellers Alexandra Sellers & Misao Hoshiai Alfreda Enwy Alfreda Enwy Alfreda Enwy Alfreda Enwy Alfreda Enwy Alfreda Enwy Alfreda Enwy Alfreda Enwy Alfreda Enwy Allison Brennan Allison Brennan Allison Brennan Allison Brennan Allison Brennan Page 3 Feuille1 Allison Brennan Allison Riley Allison Riley Amanda Quick Amanda Quick Amanda Quick Amanda Quick Amanda Quick Amanda Quick Amanda Quick Amanda Quick Amanda Quick Amanda Quick Amanda Quick Amanda Quick Amanda Quick Amanda Quick Amanda Quick Amanda Quick Amanda Quick Amanda Quick Amanda Quick Amanda Quick Amanda Quick Page 4 Feuille1 Amanda Quick Amanda Quick Amanda Quick Amanda Quick Amanda Stevens Amanda Stevens Amanda Stevens Amanda Stevens Amanda Stevens Amanda Stevens Amanda Stevens Amanda Stevens Amanda Stevens Amanda Stevens Amanda Stevens Amanda Stevens Amanda Stevens Amanda Stevens Amanda Stevens Amanda Stevens Amanda Stevens Amelia Autin & Karen Anders & Kylie Brant Amy Frazier Amy Garvey Page 5 Feuille1 Amy J. -

Talking Books on CD

Mail-A-Book Arrowhead Library System 5528 Emerald Avenue, Mountain Iron MN 55768 218-741-3840 2014 catalog no. 2 This tax-supported service from the Arrowhead Library System is available to rural residents, those who live in a city without a public library, and homebound residents living in a city with a public library. This service is available to residents of Carlton, Cook, Itasca, Koochiching, Lake, Lake of the Woods, & St. Louis Counties. Rural residents who live in the following Itasca County areas, are eligible for Mail-A-Book service Good through only if they are homebound: Town of Arbo, Town of Blackberry, June Town of Feely, Town of Grand Rapids, Town of Harris, Town of 2016 Sago, Town of Spang, Town of Wabena, City of Cohasset, City of La Prairie, and the City of Warba. Residents who are homebound in the cities of Virginia and Duluth are served by the city library. Do you need extra time to Award finish your book? You can renew it in one of three ways: 1. www.arrowhead.lib.mn.us, click on: Browse the Regional Catalog Winners click on: My Account tab 2. [email protected] 2013 Bram Stoker Award for Fiction Collection 3. 218-741-3840 or 1-800-257-1442. ____________________ The Beautiful Thing That Awaits Us All: Stories by 2014 Midwest Book Award for Humor Laird Barron Collecting interlinking tales of sublime cosmic horror, The From the Top by Michael Perry Beautiful Thing That Awaits Us All delivers enough spine- Fatherhood, wedding rings, used cars, dumpster therapy, chilling horror to satisfy even the most jaded reader. -

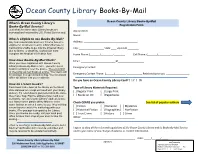

Books-By-Mail Application Form

Ocean County Library Books-By-Mail Ocean County Library Books-By-Mail What is Ocean County Library’s Registration Form Books-By-Mail Service? Just what the name says: Library books are (PLEASE PRINT) borrowed and returned by U.S. Postal Service mail. Name: _________________________________________ Who is eligible to use Books-By-Mail? Any homebound individual over 18 who has,or is Address: _______________________________________ eligible for, an Ocean County Library Borrower’s Card and is unable to get into the physical library City: __________________ State ____ Zip Code ________ due to illness or disability. A physician must complete the Medical Verification form. Home Phone: (_______)_________-________ Cell Phone: (_______)_________-________ How does Books-By-Mail Work? Email: _________________________@___________________ Once you have registered with Ocean County Library’s Books-By-Mail service, you will request Emergency Contact: ______________________________________________ books in writing or over the phone. There is a limit of checking out four books at a time. Your items will be package in a special mailer bag. Your local post Emergency Contact Phone: (______)________-___________ Relationship to you: _________________ office will deliver it to your residence. Do you have an Ocean County Library Card? [ ] Y [ ]N How do I return books? Each book is due back at the library on the latest Type of Library Materials Required: date stamped on receipt enclosed with your library [ ] Regular Print [ ] Large Print delivery. To return books, put materials in the same blue mailer bag. Flip the address index card over [ ] Books on CD [ ] Paperbacks so that the “Ocean County Library” address is face out. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Msnll\My Documents\Voyagerreports

Swofford Popular Reading Collection September 1, 2011 Title Author Item Enum Copy #Date of Publication Call Number "B" is for burglar / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11994 PBK G737 bi "F" is for fugitive / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11990 PBK G737 fi "G" is for gumshoe / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue 11991 PBK G737 gi "H" is for homicide / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11992 PBK G737 hi "I" is for innocent / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11993 PBK G737 ii "K" is for killer / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11995 PBK G737 ki "L" is for lawless / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11996 PBK G737 li "M" is for malice / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11998 PBK G737 mi "N" is for noose / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11999 PBK G737 ni "O" is for outlaw Grafton, Sue 12001 PBK G737 ou 10 lb. penalty / Dick Francis. Francis, Dick. 11998 PBK F818 te 100 great fantasy short short stories / edited by Isaac 11985 PBK A832 gr Asimov, Terry Carr, and Martin H. Greenberg, with an introduction by Isaac Asimov. 1001 most useful Spanish words / Seymour Resnick. Resnick, Seymour. 11996 PBK R434 ow 1022 Evergreen Place / Debbie Macomber. Macomber, Debbie. 12010 PBK M171 te 13th warrior : the manuscript of Ibn Fadlan relating his Crichton, Michael, 1942- 11988 PBK C928 tw experiences with the Northmen in A.D. 922. 16 Lighthouse Road / Debbie Macomber. Macomber, Debbie. 12001 PBK M171 si 1776 / David McCullough. McCullough, David G. 12006 PBK M133 ss 1st to die / James Patterson. Patterson, James, 1947- 12002 PBK P317.1 fi 204 Rosewood Lane / Debbie Macomber. Macomber, Debbie. -

Friends of the Library Newsletter Volume 4 Issue 2 Greenwood Library

Longwood University Digital Commons @ Longwood University Friends of the Library Library, Special Collections, and Archives Fall 2010 Friends of the Library Newsletter Volume 4 Issue 2 Greenwood Library Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.longwood.edu/libfriends Recommended Citation Greenwood Library, "Friends of the Library Newsletter Volume 4 Issue 2" (2010). Friends of the Library. Paper 23. http://digitalcommons.longwood.edu/libfriends/23 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Library, Special Collections, and Archives at Digital Commons @ Longwood University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Friends of the Library by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Longwood University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Special points of interest: Emilie Richards to Speak Volume 4, Issue 2 Rosemary Sprague: Longwood Educator and Award-Winning Author Fall 2010 Multimedia Expansion Honor Roll Emilie Richards to Speak at the Fall Friends of the Library Event USA Today bestselling publishing’s Oscar®, for her author, Emilie Richards, will earlier work in the genre. In speak at the Janet D. addition, Romantic Times Book Greenwood Friends of the Reviews magazine has presented Library event on Friday, her with numerous awards October 1, 2010 in the including an award for career atrium of the Greenwood achievement. Library. Richards, whose Richards is married to her name resonates with the college sweetheart, a Unitarian hundreds of thousands of Universalist minister. Richards’ readers who have embraced years with her husband and her works of family fiction church life influenced the and romance, is a full-time creation of the Ministry Is writer and avid quilter. -

Rebecca Tarvin [email protected] Dept

Rebecca Tarvin [email protected] Dept. of Integrative Biology & Museum of Vertebrate Zoology www.tarvinlab.org University of California, Berkeley RESEARCH INTERESTS My research goals are to (1) elucidate causal genetic mechanisms underlying novel traits, (2) characterize phenotypic diversification at macro- and micro-evolutionary scales, and (3) identify factors that promote and constrain biodiversity. To accomplish these goals, I link studies of natural history with functional genomics using both molecular and computational tools. My current research applies integrative methods to study origins of acquired chemical defenses and subsequent phenotypic diversification. EDUCATION 2011 – 2017 Ph.D., Biological Sciences, Evolution, Ecology, and Behavior, Dept. of Integrative Biology, University of Texas at Austin (UT). Dissertation title: Phylogenetic origins and evolutionary consequences of alkaloid resistance in poison frogs. Advisors: Dr. David Cannatella & Dr. Harold Zakon 2006 – 2010 B.A., Biology summa cum laude with Distinction and a Specialization in Ecology and Conservation Biology, Boston University (BU). Thesis title: Post-metamorphic growth of red- eyed treefrogs (Agalychnis callidryas): Variation with size at metamorphosis, foraging, and activity. Advisor: Dr. Karen Warkentin PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS 2019 – Assistant Professor, Dept. of Integrative Biology, University of California Berkeley (UCB). Assistant Curator, Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, UCB. 2018 – 2019 Postdoctoral Scholar-Fellow, Miller Institute for Basic Research in Science and the Dept. of Integrative Biology, UCB. Hosted by Dr. Rasmus Nielsen and Dr. Noah Whiteman 2017 – 2018 Postdoctoral Fellow, Dept. of Integrative Biology, University of Texas at Austin (UT), under Dr. David Cannatella. PUBLICATIONS PEER-REVIEWED JOURNAL ARTICLES (^contributed equally, †graduate student, ‡undergraduate mentee) 8. Santos, JC, RD Tarvin, LA O'Connell, D Blackburn, and LA Coloma. -

Free Shopping Guide

FREE SPRING 2017 SHOPPING GUIDE ACTION-PACKED READS Get ready for adventure with 2 new miniseries! COUPONS INSIDE! EXPERIENCE AUTHOR ALL THE RECOMMENDATIONS! ROMANCE YOU Check out which books CAN HANDLE reader-favorite authors love. THIS SPRING! MAKE A DATE WITH HARLEQUIN ON SALE JUN. 6 Spring Fling! p.18 Make a date with your favorite HARLEQUIN® SERIES and browse through the key titles so you can lose yourself in the perfect Spring romance. Ever wonder which books your favorite authors recommend? Find out now inside! p.18 Celebrate 20 years of inspirational romance with Love Inspired®! p.16 Make way for the cowboys. New York Times bestselling author ON SALE VICKI LEWIS THOMPSON MAR. 21 talks debuts in Harlequin® p.16 Special Edition with her Thunder Mountain Brotherhood cowboys! p.26 ON SALE MAY 23 p.26 APRIL MAY JUNE 22 IN EVERY ISSUE 6 A LETTER FROM THE EDITOR 8 INDULGE YOUR SHELVES What does your favorite flower say about the romance for you? 12 THE INSIDER SCOOP Mystery is behind every corner 6 with these 2 miniseries. 26 AUTHOR-IZED TELL-ALL New York Times bestselling author VICKI LEWIS THOMPSON talks about her debut in Harlequin® Special Edition. 30 SHOPPING LIST 42 FEATURES 18 AUTHOR RECOMMENDATIONS See which books reader-favorite authors recommend for you! 22 CELEBRATE MOTHER’S DAY, THE WESTERN WAY Gather up your favorite Western heroes to have a perfect Mother’s Day. 42 THRILLING NEW READS! Don’t read these after dark… EDITOR’S LETTER LOVE is in Bloom! Is there anything better than a spring romance? You start to feel a little flutter in your heart as the birds start chirping, feel JOIN warmth on your skin as the sun comes out and smell all the flowers blooming. -

The Chemistry of Man, 2007, Bernard Jensen, 1885653247, 9781885653246, Wendell W

The Chemistry of Man, 2007, Bernard Jensen, 1885653247, 9781885653246, Wendell W. Whitman Company, 2007 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1zzKMet http://www.alibris.co.uk/booksearch?browse=0&keyword=The+Chemistry+of+Man&mtype=B&hs.x=19&hs.y=26&hs=Submit DOWNLOAD http://is.gd/5xGxMr http://scribd.com/doc/29699536/The-Chemistry-of-Man http://bit.ly/1lNHRyr Dr. Jensen's Juicing Therapy Nature's Way to Better Health and a Longer Life, Bernard Jensen, Apr 1, 2000, Cooking, 176 pages. Dr. Jensen's years of study have proved the juices--both fruit and vegetable--are the fastest method for getting nutrients into our bodies. Dr. Jensen's Juicing Therapy offers. Macrobiotics for Beginners How to Achieve Health and Vitality the Oriental Way, Jon Sandifer, Bob Lloyd, 2000, Macrobiotic diet, 199 pages. Macrobiotics is a comprehensive and accessible introduction to this new and fascinating subject. The macrobiotic diet emphasises harmony with nature through adherence to a diet. Dr. Jensen's Guide to Better Bowel Care , Bernard Jensen, Sep 1, 1998, Family & Relationships, 244 pages. Based on 60 years of patient studies, this book provides specific dietary guidelines for proper bowel maintenance, along with a colonic cleansing system and effective exercise. Reference Guide for Essential Oils , Connie Higley, Alan Higley, 1998, Aromatherapy, 344 pages. Mental and Elemental Nutrients A Physician's Guide to Nutrition and Health Care, Carl Curt Pfeiffer, 1975, Medical, 519 pages. A pioneer in the field of biological psychiatry details the functions of essential nutrients, warns of the dangers of food additives, and explains nutritional therapies for. -

Titles Ordered January 11 - 18, 2018

Titles ordered January 11 - 18, 2018 Book Adult Biography Release Date: Williams, Terrie M. Black Pain : It Just Looks Like We're Not Hurting; http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1592202 1/6/2009 Real Talk for When There's No Where to Go but UP Adult Non-Fiction Release Date: Brown, Charita Cole Defying the Verdict : My Bipolar Life http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1592200 6/5/2018 Evans, Stephanie Y. (EDT)/ Bell, Kanika Black Women's Mental Health : Balancing Strength http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1592198 7/2/2018 (EDT)/ Burton, Nsenga K. (EDT) and Vulnerability Global Health Psychiatry (COR)/ Anderson, Mind Matters : A Resource Guide to Psychiatry for http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1592196 4/7/2018 Otis, III, M.d./ Benson, Timothy G., M.d./ Black Communities Berkeley, Malaika, M.d. Menakem, Resmaa, author. My grandmother's hands : racialized trauma and the http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1592197 9/19/2017 pathway to mending our hearts and bodies / Resmaa Menakem. Pierce-Baker, Charlotte This Fragile Life : A Mother's Story of a Bipolar Son http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1592201 9/1/2016 Wang, Esm̌ Weijun The Collected Schizophrenias : Essays http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1592199 2/5/2019 New Young Adult Fiction Release Date: Acevedo, Elizabeth With the Fire on High http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1592231 5/7/2019 Ahmed, Samira Internment http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1592245 3/19/2019 Ali, S. K., author. Love from A to Z / S.K. Ali. http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1592251 5/7/2019 Alsaid, Adi Brief Chronicle of Another Stupid Heartbreak http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1592239 4/30/2019 Ancrum, K. -

Read-Alike Lists

Read-Alike Lists Adult Fiction (by author) If you liked…. -Mary Kay Andrews—LuAnne Rice, Kay Hooper, Elizabeth Berg, Dorothea Benton Frank, Mary Alice Monroe, Susan Anderson, Donna Andrews, Diane Mott Davidson, Jennifer Cruisie, Joan Hess, Jane Heller, Jennifer Weiner, Carly Phillips, Marian Keyes, Erin McCarthy, Nancy Thayer, Dixie Cash, Cassandra King, Ann B. Ross, Candace Bushnell, Lauren Weisberger -Nancy Atherton—Susan Wittig Albert, M.C. Beaton, Rhys Bowen, Simon Brett, Dorothy Cannell, Carola Dunn, Hazel Holt, Diane Mott Davidson, Alexander McCall Smith, Lillian Jackson Braun -Jean M. Auel—James Michener, Diana Gabaldon, Bernard Cornwell, Sue Harrison, Ken Follett, William Sarabande, Kathleen O’Neal Gear, Juliet Marillier, Michelle Paver, Steven Barnes, Joan Wolf, Sara Donati, Mary Mackey -M.C. Beaton—Agatha Christie, Lillian Jackson Braun, Rhys Bowen, Simon Brett, Emily Brightwell, Dorothy Cannel, Laura Childs, Cleo Coyle, Jeanne M. Dams, Carola Dunn, Carolyn Hart, Carolyn Hart, Joan Hess, Hazel Holt, Betty Rowlands, Elizabeth Spann Craig, Diana Mott Davidson, Patricia Sprinkle -Maeve Binchy—Rosamunde Pilcher, Robin Pilcher, Janet Dailey, Joanna Trollope, Lynne Hinton, Elizabeth Goudge, Joyce Carol Oates, Belva Plain, Anne Tyler, Eugenia Price, Anne Rivers Siddons, Colleen McCullough, Thomas Berger, Joanne Greenberg, Barbara Taylor Bradford, Marcia Willett -Terry Brooks—Robin Hobb, Raymond Feist, Robert Jordan, Ursula K. LeGuin, J.R.R. Tolkien, David Farland, Mercedes Lackey, Morgan Howell, Tad Williams, R.A. Salvatore, Piers Anthony, -

Adult Author's New Gig Adult Authors Writing Children/Young Adult

Adult Author's New Gig Adult Authors Writing Children/Young Adult PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 31 Jan 2011 16:39:03 UTC Contents Articles Alice Hoffman 1 Andre Norton 3 Andrea Seigel 7 Ann Brashares 8 Brandon Sanderson 10 Carl Hiaasen 13 Charles de Lint 16 Clive Barker 21 Cory Doctorow 29 Danielle Steel 35 Debbie Macomber 44 Francine Prose 53 Gabrielle Zevin 56 Gena Showalter 58 Heinlein juveniles 61 Isabel Allende 63 Jacquelyn Mitchard 70 James Frey 73 James Haskins 78 Jewell Parker Rhodes 80 John Grisham 82 Joyce Carol Oates 88 Julia Alvarez 97 Juliet Marillier 103 Kathy Reichs 106 Kim Harrison 110 Meg Cabot 114 Michael Chabon 122 Mike Lupica 132 Milton Meltzer 134 Nat Hentoff 136 Neil Gaiman 140 Neil Gaiman bibliography 153 Nick Hornby 159 Nina Kiriki Hoffman 164 Orson Scott Card 167 P. C. Cast 174 Paolo Bacigalupi 177 Peter Cameron (writer) 180 Rachel Vincent 182 Rebecca Moesta 185 Richelle Mead 187 Rick Riordan 191 Ridley Pearson 194 Roald Dahl 197 Robert A. Heinlein 210 Robert B. Parker 225 Sherman Alexie 232 Sherrilyn Kenyon 236 Stephen Hawking 243 Terry Pratchett 256 Tim Green 273 Timothy Zahn 275 References Article Sources and Contributors 280 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 288 Article Licenses License 290 Alice Hoffman 1 Alice Hoffman Alice Hoffman Born March 16, 1952New York City, New York, United States Occupation Novelist, young-adult writer, children's writer Nationality American Period 1977–present Genres Magic realism, fantasy, historical fiction [1] Alice Hoffman (born March 16, 1952) is an American novelist and young-adult and children's writer, best known for her 1996 novel Practical Magic, which was adapted for a 1998 film of the same name. -

2020 Catalog No. 1 | Save This Catalog | Good Through December 2021

MAIL-A-BOOK 2020 CATALOG NO. 1 | SAVE THIS CATALOG | GOOD THROUGH DECEMBER 2021 5528 EMERALD AVENUE, MOUNTAIN IRON, MINNESOTA 55768 218-741-3840 | www.alslib.info | [email protected] Mail-A-Book Arrowhead Library System 5528 Emerald Avenue Mountain Iron, MN 55768-2069 218-741-3840 (Main Office) 1-800-257-1442 (Toll Free) 218-748-2171 (FAX) [email protected] www.alslib.info/services/mail-a-book www.facebook.com/alslibinfo Table of Contents Audiobooks ......................................... 1 Bestsellers ............................................ 4 Cookbooks, Health & Parenting ......... 7 DVDs ................................................... 9 Fiction ................................................ 16 Home & Garden ................................ 20 Inspirational ....................................... 21 Juvenile Non-Fiction ......................... 23 Middle Readers ................................. 25 Minnesota Books ............................... 28 Fiction....................................... 28 Non-Fiction .............................. 29 Music CDs ......................................... 30 Mystery .............................................. 30 Non-Fiction ....................................... 33 Old Favorites ..................................... 36 Picture Books .................................... 36 Board Books ............................. 38 Book and CD Sets .................... 38 Romance ............................................ 38 Harlequin Bookmark ................ 42 Love Inspired Bookmark