Almost Memories / Almost True Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

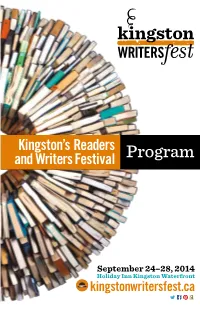

2014 Program

Kingston’s Readers and Writers Festival Program September 24–28, 2014 Holiday Inn Kingston Waterfront kingstonwritersfest.ca OUR MANDATE Kingston WritersFest, a charitable cultural organization, brings the best Welcome of contemporary writers to Kingston to interact with audiences and other artists for mutual inspiration, education, and the exchange of ideas that his has been an exciting year in the life of the Festival, as well literature provokes. Tas in the book world. Such a feast of great books and talented OUR MISSION Through readings, performance, onstage discussion, and master writers—programming the Festival has been a treat! Our mission is to promote classes, Kingston WritersFest fosters intellectual and emotional growth We continue many Festival traditions: we are thrilled to welcome awareness and appreciation of the on a personal and community level and raises the profile of reading and bestselling American author Wally Lamb to the International Marquee literary arts in all their forms and literary expression in our community. stage and Wayson Choy to deliver the second Robertson Davies lecture; to nurture literary expression. Ben McNally is back for the Book Lovers’ Lunch; and the Saturday Night BOARD OF DIRECTORS 2014 FESTIVAL COORDINators SpeakEasy continues, in the larger Bellevue Ballroom. Chair | Jan Walter Archivist | Aara Macauley We’ve added new events to whet your appetite: the Kingston Vice-Chairs | Michael Robinson, Authors@School, TeensWrite! | Dinner Club with a specially designed menu; a beer-sampling Jeanie Sawyer Ann-Maureen Owens event; and with kids events moved offsite, more events for adults on T Secretary Box Office Services T | Michèle Langlois | IO Sunday. -

Library Matters @ Mcgill V Olume 6 | Issue 5

library matters @ mcgill v olume 6 | issue 5 The Honourable Ken Dryden mingles with fans as part of the Library Matters @ McGill Hugh MacLennan Memorial Lecture presented by the Friends of the Volume 6 | Issue 5 | September-October 2010 Library and the McGill Bookstore. FROM THE DIRECTOR OF LIBRARIES ecently Ken Dryden visited McGill time when a user would like a tour of as part of the Hugh MacLennan the facilities and we offer assistance when Diane Koen, RMemorial Lecture hosted by the a colleague is looking for help. This and director of Friends of the Library. When asked what every issue of Library Matters, is a living libraries kind of impact the library had on his life, he record of the stories that tell of the collective (Interim) was quick to answer,“I didn’t read a lot as a commitment and drive we have in our work. kid. I started reading really in university and The spirit of giving is not a seasonal thing then I got my real chance after that when I to us and we take pride in the services we was playing hockey. With all those times on provide to faculty, students and the broader airplanes, buses, hotel rooms and late nights community. It is of no surprise then that I INSIDE THIS ISSUE after games when I couldn’t sleep, I got a reach out to you to donate to the McGill second chance to read. That’s when it really Centraide Campaign. DIgitizatioN REpRoductioN: on page 2 opened up to me. A couple of the books I TEchnology: on page 3 wrote required quite a lot of research. -

523 Book Reviews

Book Reviews significant increase in research into Welsh Wales into the background. For example, in the medical history, with many good studies, chapter by Hirst, and in the contribution by Medicine in Wales is a welcome addition to what Richard Coopey and Owen Roberts on the is still a limited historiography. municipalization of water, the Welsh dimension As the editor makes clear, Medicine in Wales is is subordinate to a metropolitan or English designed to ‘‘illustrate the growing corpus of history. David Greaves in his synthesis of debates research-based material’’ (p. 2) on the social about inequalities in health and medical care history of medicine and health in Wales. Its makes little reference to Wales despite the content is deliberately diverse. The contributors problems the region faced. Given the peculiar draw on a range of sources from documentary economic, social, and political milieu of Wales, records to oral testimony to film to examine the this seems a missed opportunity. relationship between the public and private Despite this criticism, the volume has its provision of healthcare since c. 1800. This strengths. For example, Michael in her telling relationship provides the intellectual context for analysis of suicide in north Wales examines how the volume. Drawing on Juurgen€ Habermas’s the Denbigh asylum came to replace the family as notion of the public and private sphere, the a source of care and how suicide was contributorsraisequestionsabouttheutilityofthis medicalized. Coopey and Roberts add further approach by examining issues of class, gender, weight to the need to revise the heroic participation and citizenship, and the role of the historiography of state intervention. -

Governor General's Literary Awards

Bibliothèque interculturelle 6767, chemin de la Côte-des-neiges 514.868.4720 Governor General's Literary Awards Fiction Year Winner Finalists Title Editor 2009 Kate Pullinger The Mistress of Nothing McArthur & Company Michael Crummey Galore Doubleday Canada Annabel Lyon The Golden Mean Random House Canada Alice Munro Too Much Happiness McClelland & Steward Deborah Willis Vanishing and Other Stories Penguin Group (Canada) 2008 Nino Ricci The Origins of Species Doubleday Canada Rivka Galchen Atmospheric Disturbances HarperCollins Publishers Ltd. Rawi Hage Cockroach House of Anansi Press David Adams Richards The Lost Highway Doubleday Canada Fred Stenson The Great Karoo Doubleday Canada 2007 Michael Ondaatje Divisadero McClelland & Stewart David Chariandy Soucoupant Arsenal Pulp Press Barbara Gowdy Helpless HarperCollins Publishers Heather O'Neill Lullabies for Little Criminals Harper Perennial M. G. Vassanji The Assassin's Song Doubleday Canada 2006 Peter Behrens The Law of Dreams House of Anansi Press Trevor Cole The Fearsome Particles McClelland & Stewart Bill Gaston Gargoyles House of Anansi Press Paul Glennon The Dodecahedron, or A Frame for Frames The Porcupine's Quill Rawi Hage De Niro's Game House of Anansi Press 2005 David Gilmour A Perfect Night to Go to China Thomas Allen Publishers Joseph Boyden Three Day Road Viking Canada Golda Fried Nellcott Is My Darling Coach House Books Charlotte Gill Ladykiller Thomas Allen Publishers Kathy Page Alphabet McArthur & Company GovernorGeneralAward.xls Fiction Bibliothèque interculturelle 6767, -

Longlisted & Shortlisted Books 1994-2018

Longlisted & Shortlisted Books 1994-2018 www.scotiabankgillerprize.ca # The Boys in the Trees, Mary Swan – 2008 13 Ways of Looking at a Fat Girl, Mona Awad - 2016 Brother, David Chariandy – 2017 419, Will Ferguson - 2012 Burridge Unbound, Alan Cumyn – 2000 By Gaslight, Steven Price – 2016 A A Beauty, Connie Gault – 2015 C A Complicated Kindness, Miriam Toews – 2004 Casino and Other Stories, Bonnie Burnard – 1994 A Fine Balance, Rohinton Mistry – 1995 Cataract City, Craig Davidson – 2013 The Age of Longing, Richard B. Wright – 1995 The Cat’s Table, Michael Ondaatje – 2011 A Good House, Bonnie Burnard – 1999 Caught, Lisa Moore – 2013 A Good Man, Guy Vanderhaeghe – 2011 The Cellist of Sarajevo, Steven Galloway – 2008 Alias Grace, Margaret Atwood – 1996 Cereus Blooms at Night, Shani Mootoo – 1997 Alligator, Lisa Moore – 2005 Childhood, André Alexis – 1998 All My Puny Sorrows, Miriam Toews – 2014 Cities of Refuge, Michael Helm – 2010 All That Matters, Wayson Choy – 2004 Clara Callan, Richard B. Wright – 2001 All True Not a Lie in it, Alix Hawley – 2015 Close to Hugh, Mariana Endicott - 2015 American Innovations, Rivka Galchen – 2014 Cockroach, Rawi Hage – 2008 Am I Disturbing You?, Anne Hébert, translated by The Colony of Unrequited Dreams, Wayne Johnston – Sheila Fischman – 1999 1998 Anil’s Ghost, Michael Ondaatje – 2000 The Colour of Lightning, Paulette Jiles – 2009 Annabel, Kathleen Winter – 2010 Conceit, Mary Novik – 2007 An Ocean of Minutes, Thea Lim – 2018 Confidence, Russell Smith – 2015 The Antagonist, Lynn Coady – 2011 Cool Water, Dianne Warren – 2010 The Architects Are Here, Michael Winter – 2007 The Crooked Maid, Dan Vyleta – 2013 A Recipe for Bees, Gail Anderson-Dargatz – 1998 The Cure for Death by Lightning, Gail Arvida, Samuel Archibald, translated by Donald Anderson-Dargatz – 1996 Winkler – 2015 Curiosity, Joan Thomas – 2010 A Secret Between Us, Daniel Poliquin, translated by The Custodian of Paradise, Wayne Johnston – 2006 Donald Winkler – 2007 The Assassin’s Song, M.G. -

In Transit. Aspects of Transculturalism in Janice Kulyk Keefer's Travels

UNIVERSITY OF UMEÅ DISSERTATION ISSN 0345-0155 ISBN 91-7191-211-8 From the Department of English, Faculty of Humanities, Umeå University, Sweden In Transit Aspects of Transculturalism in Janice Kulyk Keefer’s Travels AN ACADEMIC DISSERTATION which will, on the proper authority of the Chancellor’s Office of Umeå University for passing the doctoral examination, be publicly defended in hörsal F, Humanisthuset, on Saturday, 14th September, 1996, at 10.15 a.m. Elisabeth Mårald Umeå University Umeå 1996 Abstract Transculturalism refers to how cultural barriers are transcended and how cultures meet. Because the transcultural perspective reflects hitherto unrepresented spaces, it revises and innovates literary canons. This study investigates aspects of transculturalism in texts dealing with travel by the Canadian writer Janice Kulyk Keefer. It also explores how these aspects might alter our view of Canadian literature. The transcultural perspectives between mainstream Canada and Ukraine, Europe and Acadie have been analysed through three tropes of travel: departure, passage and arrival. Keefer’s texts have been read in accordance with Mikhail Bakhtin's dialogic theories to chart transcultural encounters and clashes. This thesis argues that a historic consciousness of their ethnic group gives the young generation a transcultural position that enables them to profit from their dual cultural competence. Although Imagined Communities are affirmed as receptacles of the cultural heritage, the impending environmental catastrophe demands that the national interests that they represent be abandoned for international co-operation. In Keefer’s European texts the transcultural aspects reflect how travel becomes synonymous with quests and epiphanies. Travelling is described as a learning process inRest Harrow where the protagonist’s increasing cultural competence changes her from a tourist to a real traveller. -

Box Office 0870 343 1001 the Radcliffe Camera, the Bodleian Library

Sunday 29 March – Sunday 5 April 2009 at Christ Church, Oxford Featuring Mario Vargas Llosa Ian McEwan Vince Cable Simon Schama P D James John Sentamu Robert Harris Joan Bakewell David Starkey Richard Holmes A S Byatt John Humphrys Philip Pullman Michael Holroyd Joanne Harris Jeremy Paxman Box Office 0870 343 1001 www.sundaytimes-oxfordliteraryfestival.co.uk The Radcliffe Camera, The Bodleian Library. The Library is a major new partner of the Festival. WELCOME Welcome We are delighted to welcome you to the 2009 Sunday Particular thanks this year to our partners at Times Oxford Literary Festival - our biggest yet, The Sunday Times for their tremendous coverage spread over eight days with more than 430 speakers. and support of the Festival, and to all our very We have an unprecedented and stimulating series generous sponsors, donors and supporters, of prestige events in the magnificent surroundings especially our friends at Cox and Kings Travel. of Christ Church, the Sheldonian Theatre and We have enlarged and enhanced public facilities Bodleian Library. But much also to amuse and divert. in the marquees at Christ Church Meadow and in the Master’s Garden, which we hope you will Ticket prices have been held to 2008 levels, offering enjoy. We are very grateful to the Dean, the outstanding value for money, so that everyone Governing Body and the staff at Christ Church for can enjoy a host of national and international their help and support. speakers, talking, conversing and debating throughout the week on every conceivable topic. Hitherto, the Festival has been a ‘Not for Profit’ Company, but during 2009 we will move to establish The Sunday Times Oxford Festival is dedicated a new Charitable Trust. -

The Literary Market in the UK

The Literary Market in the UK edited by Amrei Katharina Nensel and Christoph Reinfandt Faculty of Humanities English Literatures and Cultures The Literary Market in the UK Editors Amrei Katharina Nensel, Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen Prof. Dr. Christoph Reinfandt, Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen © Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen and the authors 2017 Design and layout Amrei Katharina Nensel and Christoph Reinfandt Cover Images Fotolia©Maksym Yemelyanov Fotolia©spr Fotolia©olly Further information http://www.uni-tuebingen.de/angl/ i Contents List of Figures iii Preface iv Contributors v The Present in Perspective: Mapping the Literary Market Today 1 Christoph Reinfandt British Publishing and the Rise of Creative Writing: A Personal View 19 Blake Morrison Discounted and Digital: British Publishing in the Wake of the Net Book Agreement 35 Amrei Katharina Nensel The Impact of Digital Publishing on the Literary Market 55 Sophie Rochester The Postcolonial Writer as Commodity 69 Ellen Dengel-Janic The Ever-Changing Rules: Acquiring, Editing and Publishing Literary Fiction in the UK 81 Interview with Alex Bowler Literary Reviews: Past, Present, Future 101 Interview with Erica Wagner The Reception of Literary Fiction in the Digital Age: The Democratisation of Reviewing in Reading Groups 109 Interview with Irene Haynes ii List of Figures Figure 1: The Market-Marketplace-Matrix 10 Figure 2: The Circuit of the Book 38 Figure 3: The Publishers’ Profit Margin in Relation to Sales Revenue 42 Figure 4: Number of Titles Published in the UK 46 Figure 5: Market Share of UK Book Retail Sales by Type of Outlet by Value 48 Figure 6: Market Share of UK Book Retail Sales by Type of Outlet by Volume 49 iii Preface The Literary Market in the UK collects material which emerged in the wake of a highly suc- cessful lecture series of the same title, presented at the University of Tuebingen in summer term 2011. -

Autumn 2004 Volume 18

CON TROVERSY LOOKOUT #17 • a forum for writers 3516 W. 13th Ave., Vancouver, BC V6R 2S3 LOOKOUTLOOKOUT LOOKOUT7REASONS why the British explorer didn’t reach British Columbia in 1579. Edward Von DOUBTING der Porten is one of many and named them the Isles of ? Saint James. Saint James’ Day naval schol- is July 25. So Drake did not ars who have leave the islands on August 25 as Bawlf claims, but on July 25. The calendar as given taken extremeDRAKE objection to in the contemporary accounts is the correct one. This leaves Drake 14 days—not 44—to carry out his explorations Samuel Bawlf’s The Secret between his arrival on the coast and his arrival at the port. Voyage of Sir Francis Drake With no stops, his day-and-night speed to travel 2,000 miles would have had to be 5.95 knots average, or 142.8 (D&M 2003). Its marketing miles per day in a three-to-four-knot ship capable of less leads one to assume Francis than one knot in daylight along an unknown shore. For Drake to explore 2,000 miles of the northwest coast in Drake was the first European 14 days—the amount of time he had available to spend on exploration—is impossible. to reach British Columbia. 4. The Native-American peoples Drake met were de- “Bawlf’s book is fantasy on the same plane as 1421, Vi- scribed in great detail in the accounts. Bawlf claims Drake kings in Minnesota and ancient astronauts,” says Von der Porten. “Serious research has long resolved the issues of where met the peoples who inhabited the shore from southern Drake traveled in the Pacific, and British Columbia could Alaska to central Oregon: northwest-coast peoples with not have been a place he visited.” huge cedar canoes, split-plank communal houses and to- Given that Bawlf’s book received ample coverage in B.C. -

524 Book Reviews

Book Reviews (Manchester University Press, 2002). Now, with through Dowbiggin’s history is the tension this new book by Ian Dowbiggin, we have a between public authority and personal companion volume that charts the history of the autonomy, between paternalism and individual euthanasia movement in modern America. freedom. He ends with the new issues posed Opening with the Jack Kevorkian case, by September 11, and concludes that the question Dowbiggin’s book has six short chapters. The of ‘‘where does the freedom to die end and the first charts the history of euthanasia as a concept duty to die begin’’ remains unanswered (p. 177). and a practice from classical Antiquity to the One of the difficulties faced by Dowbiggin is Progressive era. The next, entitled that he has to contend with a large cast of ‘Breakthrough’, covers the period 1920–40, and individuals (Felix Adler; William J Robinson; the establishment of the Euthanasia Society of Charles Francis Potter; Charles Killick Millard; America (ESA) in 1938. The third chapter, called Inez Celia Philbrick; Eleanor Dwight Jones; ‘Stalemate’, surveys the struggles of the ESA Joseph Fletcher; and Olive Ruth Russell among with the Roman Catholic church in the years others). Similarly, by the 1970s the picture 1940–60. Chapter four, ‘Riding a great wave’, becomes very complex as the movement deals with the period between 1960 and 1975, fractured into numerous smaller organizations including the reinvention of the ESA with the with frequent name changes (the Society for the idea of passive euthanasia in the 1960s. The Right to Die; Concern for Dying; the Hemlock following chapter, ‘Not that simple’, covers the Society; Choice in Dying; Partnership for Caring, splits that characterized the 1970s, and the and so on). -

Where Have All the Babies Gone? the “Birth Dearth” and What to Do About It

No. 3 Fall 2006-09-26 Canadian Family Views Institute of Marriage and Family Canada WHERE HAVE ALL THE BABIES GONE? THE “BIRTH DEARTH” AND WHAT TO DO ABOUT IT PRESENTED BY DR. IAN DOWBIGGIN, UPEI, ON SEPTEMBER 26, 2006 AT THE IMFC FAMILY POLICY CONFERENCE, OTTAWA, ON, CANADA Canadian Family Views is an occasional series produced by the Institute of Marriage and Family Canada that examines the public opinions of Canadians on issues impacting family life. Some call it the “birth dearth.” Others refer to it as the “empty cradle” or the coming “demographic winter.” Yet, no matter what people call it, they’re talking about the same thing: the dramatic drop in the birth rate over the last fifty years.1 In the words of U.S. author Ben Wattenberg, “never have birth and fertility rates fallen so far, so fast, so low, for so long, and in so many places, so surprisingly.”2 From the prestigious pages of Foreign Affairs, the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, and Germany’s Der Spiegel, to a rash of new books, experts predict this “birth dearth” in many countries could cripple future generations. As the baby boomers approach retirement age and the pool of young workers shrinks, anxious governments wonder if costly social programs such as medicare and social security will survive in the coming years. That includes the Peoples’ Republic of China, where roughly one out of every five of the world’s people reside.3 Currently gripping the attention of presidents, prime ministers and popes, the birth dearth touches virtually every facet of human life. -

Dr. Jack Kevorkian's Life and the Battle to Le

The American Journal of Bioethics movement as well as both the Glucksberg and Quill Supreme courses in both the sacred (Christian conservative evangel- Court cases, corrects common misrepresentations of two ical) and secular university environments and, overwhelm- controversial cases in Oregon, drawing on his experience ingly, my students found an invaluable resource in this as a clinician at the bedside and in the case of these patients. definitive collection of 35 essays from 43 men and women Barbara Coombs Lee, a nurse and a lawyer and the exec- representing diverse backgrounds and stances on the issues utive director of the Compassion of Dying. Johannes van of physician-assisted dying, patient choice, and palliative Delden, Jaap Visser and Els Borst-Eilers review 20 years’ ex- care. As one reviewer of The Case Against Assisted Suicide perience in the Netherlands, including three major nation- volume aptly noted, detractors of works of this sort might wide studies and an account of the distortion of this data attempt to criticize it for being what it is not. It is not a by Hendin and other American authors. Herman van der detailed analysis of the principles and ethics of palliative Kloot Meijburg, former director of bioethics for the Dutch care and it is not an attempt to present wholly new argu- Hospital Association, as already discussed, provides a vivid ments regarding the case for or against physician-assisted personal account of his father’s death in a country in which suicide. It is also not a scientific treatise in the form of a active voluntary euthanasia and physician assistance in sui- logical analysis on whether or not any particular argument cide are legal.