4.7. Tracing Back Lipstick. Glam Narratives in Popular History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2004 General Catalog

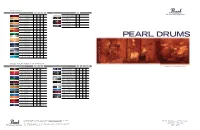

MASTERS SERIES Masters Series Lacquer Finish . Available Colors MMX MRX MHX BRX Masters Series Covered Finish . Available Colors MSX No.100 Wine Red No.400 White Marine Pearl No.102 Natural Maple No.401 Royal Gold No.103 Piano Black No.402 Abalone No.112 Natural Birch No.403 Red Onyx No.122 Black Mist No.404 Amethyst No.128 Vintage Sunburst No.141 Red Mahogany No.148 Emerald Fade No.151 Platinum Mist PEARL DRUMS No.152 Antique Gold No.153 Sunrise Fade m No.154 Midnight Fade o c . No.156 Purple Storm m No.160 Silver Sparkle u r d No.165 Diamond Burst l r No.166 Black Sparkle a e p No.168 Ocean Sparkle . w w w SESSION / EXPORT / FORUM / RHYTHM TRAVELER . Lacquer Finish Available Colors SMX SBX ELX Covered Finish Available Colors EXR EX FX RT www.pearldrum.com No.281 Carbon Mist No.430 Prizm Blue No.290 Vintage Fade No.431 Strata Black No.291 Cranberry Fade No.432 Prizm Purple No.292 Marine Blue Fade No.433 Strata White No.296 Green Burst No.21 Smokey Chrome No.280 Vintage Wine No.31 Jet Black No.283 Solid Black No.33 Pure White No.284 Tobacco Burst No.49 Polished Chrome No.289 Blue Burst No.78 Teal Metallic No.271 Ebony Mist No.91 Red Wine No.273 Blue Mist No.95 Deep Blue No.274 Amber Mist No.98 Charcoal Metallic No.294 Amber Fade No.295 Ruby Fade No.299 Cobalt Fade For more information on these or any Pearl product, visit your local authorized Pearl Dealer. -

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Audacity Find Clipping

Audacity find clipping Continue See also: List of songs about California Wikimedia related to the song list article This is a list of songs about Los Angeles, California: either refer, are set there, named after a place or feature of a city named after a famous resident, or inspired by an event that occurred locally. In addition, several adjacent communities in the Greater Los Angeles area, such as West Hollywood, Beverly Hills, Santa Monica, Pasadena, Inglewood and Compton are also included in this list, despite the fact that they are separate municipalities. The songs are listed by those who are notable or well-known artists. Songs #s-A 10th and Crenshaw Fatboy Slim 100 Miles and Runnin' at N.W.A 101 Eastbound on Fourplay 103rd St. Theme Watts 103rd Street Rhythm Band 1977 Sunset Strip at Low Numbers 2 A.M. on Bobby Mulholland Drive Please, and Udenik 2 David Banner 21 Snoopstreet Trey Deee 26 Miles (Santa Catalina) at Four Preps 2 Nigs United 4 West Compton Prince 29th Street David Benoit 213 to 619 Adjacent Abstract. at Los Angeles Joe Mama 30 Piers Avenue Andrew Hill 319 La Cienega Tony, Vic and Manuel 34th Street in Los Angeles Dan Cassidy 3rd Base, Dodger Stadium Joe Kewani (Rebuilt Paradise Cooder) 405 by RAC Andre Allan Anjos 4pm in Calabasas Drake (musician) 5 p.m. to Los Angeles Julie Covington 6 'N Mornin' by Ice-T 64 Bars at Wilshire Barney Kessel 77 Sunset Strip from Alpinestars 77 Sunset Sunset Strip composers Mack David and Jerry Livingston 79th and Sunset Humble Pye 80 blocks from Silverlake People under the stairs 808 Beats Unknown DJ 8069 Vineland round Robin 90210 Blackbeard 99 miles from Los Angeles Art Garfunkel and Albert Hammond Malibu Caroline Loeb .. -

Playlist Rock Classique 26 Fevrier 2021

Animateurs : Alain Lefebvre et le Dr. Pendragon Émission #1181 Date : 26 février 2021 Heure : 11:00 à 17:00 Baladodiffusion : https://archive.org/details/rock-classique-26-fevrier-2021-complete Vendredi 26 février 2021 Première partie du « Spécial 1981 » à Rock Classique Alain Lefebvre et le Docteur Pendragon vous ont préparé une émission très spéciale ce vendredi puisqu’elle sera entièrement consacrée à l’année 1981. Au programme vous retrouverez des artistes tels : Joe Walsh, Van Halen, Frank Zappa, April Wine, Journey, Judas Priest, The Who, Rush, The Moody Blues, ZZ Top, Def Leppard, The Ramones, The Exploited, Ted Nugent et Motörhead. Alain vous présentera aussi une face complète d’un album vinyle classique qui a marqué l’année 1981 soit Killers d’Iron Maiden. Tout ça en plus de la Chronique des groupes obscurs , Les Éphémérides du Rock , ainsi que tous les segments qui font l’originalité de l’émission. Un autre programme qui devrait plaire aux vrais amateurs de vrai Rock. Rock Classique , tous les vendredis de 11h00 à 17h00, en reprise les lundis de 12h00 à 18h00. Canevas Rock Classique 26 février 2021 (émission #1181) Artiste/groupe Titre de la pièce Album et année de sortie 1 Headgirl Please Don’t Touch St.Valentine’s Day Massacre (13 février) 2 Joe Walsh Life of Illusions There Goes the Neighborhood (? Mai) 3 Praying Mantis Rich City Kids Time Tells No Lies (20 mars) 4 Praying Mantis Panic in the Streets Time Tells No Lies (20 mars) 5 Hanoi Rocks Tragedy Bangkok Shocks, Saigon Kicks, Hanoi Rocks (? Février) 6 Billy Squier The Stroke Don’t Say No (13 avril) 7 The Tubes Talk To Ya Later The Completion Backward Principle (6 avril) 8 UFO Profession of Violence The Wild, The Willing and the Innocent (6 janvier) 9 The Moody Blues Gemini Dream Long Distance Voyager (15 mai) 10 Frank Zappa I Ain’t Go No Heart/Tell Me You Love Me Tinseltown Rebellion (17 mai) 11 Journey Majestic/Where Were You Captured (30 janvier) 12 38. -

Songs by Artist 08/29/21

Songs by Artist 09/24/21 As Sung By Song Title Track # Alexander’s Ragtime Band DK−M02−244 All Of Me PM−XK−10−08 Aloha ’Oe SC−2419−04 Alphabet Song KV−354−96 Amazing Grace DK−M02−722 KV−354−80 America (My Country, ’Tis Of Thee) ASK−PAT−01 America The Beautiful ASK−PAT−02 Anchors Aweigh ASK−PAT−03 Angelitos Negros {Spanish} MM−6166−13 Au Clair De La Lune {French} KV−355−68 Auld Lang Syne SC−2430−07 LP−203−A−01 DK−M02−260 THMX−01−03 Auprès De Ma Blonde {French} KV−355−79 Autumn Leaves SBI−G208−41 Baby Face LP−203−B−07 Beer Barrel Polka (Roll Out The Barrel) DK−3070−13 MM−6189−07 Beyond The Sunset DK−77−16 Bill Bailey, Won’t You Please Come Home? DK−M02−240 CB−5039−3−13 B−I−N−G−O CB−DEMO−12 Caisson Song ASK−PAT−05 Clementine DK−M02−234 Come Rain Or Come Shine SAVP−37−06 Cotton Fields DK−2034−04 Cry Like A Baby LAS−06−B−06 Crying In The Rain LAS−06−B−09 Danny Boy DK−M02−704 DK−70−16 CB−5039−2−15 Day By Day DK−77−13 Deep In The Heart Of Texas DK−M02−245 Dixie DK−2034−05 ASK−PAT−06 Do Your Ears Hang Low PM−XK−04−07 Down By The Riverside DK−3070−11 Down In My Heart CB−5039−2−06 Down In The Valley CB−5039−2−01 For He’s A Jolly Good Fellow CB−5039−2−07 Frère Jacques {English−French} CB−E9−30−01 Girl From Ipanema PM−XK−10−04 God Save The Queen KV−355−72 Green Grass Grows PM−XK−04−06 − 1 − Songs by Artist 09/24/21 As Sung By Song Title Track # Greensleeves DK−M02−235 KV−355−67 Happy Birthday To You DK−M02−706 CB−5039−2−03 SAVP−01−19 Happy Days Are Here Again CB−5039−1−01 Hava Nagilah {Hebrew−English} MM−6110−06 He’s Got The Whole World In His Hands -

Karaoke Book

10 YEARS 3 DOORS DOWN 3OH!3 Beautiful Be Like That Follow Me Down (Duet w. Neon Hitch) Wasteland Behind Those Eyes My First Kiss (Solo w. Ke$ha) 10,000 MANIACS Better Life StarStrukk (Solo & Duet w. Katy Perry) Because The Night Citizen Soldier 3RD STRIKE Candy Everybody Wants Dangerous Game No Light These Are Days Duck & Run Redemption Trouble Me Every Time You Go 3RD TYME OUT 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL Going Down In Flames Raining In LA Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 3T 10CC Here Without You Anything Donna It's Not My Time Tease Me Dreadlock Holiday Kryptonite Why (w. Michael Jackson) I'm Mandy Fly Me Landing In London (w. Bob Seger) 4 NON BLONDES I'm Not In Love Let Me Be Myself What's Up Rubber Bullets Let Me Go What's Up (Acoustative) Things We Do For Love Life Of My Own 4 PM Wall Street Shuffle Live For Today Sukiyaki 110 DEGREES IN THE SHADE Loser 4 RUNNER Is It Really Me Road I'm On Cain's Blood 112 Smack Ripples Come See Me So I Need You That Was Him Cupid Ticket To Heaven 42ND STREET Dance With Me Train 42nd Street 4HIM It's Over Now When I'm Gone Basics Of Life Only You (w. Puff Daddy, Ma$e, Notorious When You're Young B.I.G.) 3 OF HEARTS For Future Generations Peaches & Cream Arizona Rain Measure Of A Man U Already Know Love Is Enough Sacred Hideaway 12 GAUGE 30 SECONDS TO MARS Where There Is Faith Dunkie Butt Closer To The Edge Who You Are 12 STONES Kill 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER Crash Rescue Me Amnesia Far Away 311 Don't Stop Way I Feel All Mixed Up Easier 1910 FRUITGUM CO. -

Jazzing the Music Mix NASHVILLE- Two Number One Songs by Garth

Jazzing the Music Mix NASHVILLE- Two number one songs by Garth Brooks-and she’s not even country!In the world of jazz, Benita Hill’s one-two punch is hitting its mark. The former background singer for the Allman Brothers Band released her first critically acclaimed CD, Fan The Flame, and established herself as a silky-voiced stylist and hit songwriter.In addition to Brooks, Hill’s songs have been recorded by Isaac Hayes and Kirk Whalum, among others. Her live performances regularly receive accolades and Hill has shared the stage with such jazz/pop luminaries as Boney James, Chuck Mangione, Kirk Whalum Michael Franks and Yolanda Adams, to mention a few. Fan the Flame elicited these raves: “One of the top ten albums of the year”(Entertainment At Home),”An immensely involving vocalist”(Billboard),”Sexy enough to put a eunuch in the mood”(Charles Earle, In Review),”Music with a languid, timeless quality that draws on pop standards and cocktail jazz...a stylist on the order of Julie London or Peggy Lee”(Michael McCall, Nashville Scene),”An exquisitely crafted recording from an amazing talent”(Brent Clanton,KODA,Houston). Her second CD, Tangerine Moon, features the title cut and fourteen songs ranging from the sultry Southern style “Dream About You” to a swinging “More Money”. Jazz from Nashville? Jazz at its purest freely interprets myriad influences.Benita’s standard-sounding original songs crossed so many boundaries that even Garth Brooks is a fan and was moved to record three of her compositions.”Take The Keys To My Heart” and “Two Pina Coladas” (also a #1 single) were on his Sevens album and “It’s Your Song” (renamed as a dedication to his mother) was the first single from his Double Live CD. -

Hanoi Rocks People Like Me Mp3, Flac, Wma

Hanoi Rocks People Like Me mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: People Like Me Country: Finland Released: 2002 MP3 version RAR size: 1766 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1994 mb WMA version RAR size: 1709 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 406 Other Formats: MP2 ASF MIDI FLAC RA MP2 MP4 Tracklist 1 People Like Me 2:56 2 Lucky 3:20 3 Winged Bull 4:30 4 People Like Me (Enhanced Video Track) Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Akashic Rocks Copyright (c) – Akashic Rocks Pressed By – Måndag Oy Credits Backing Vocals – Andy McCoy, Costello Hautamäki, Michael Monroe Bass – Timpa Laine Drums – Lacu Lahtinen Guitar – Andy McCoy, Costello Hautamäki, Michael Monroe Lead Vocals – Michael Monroe Percussion – Lacu Lahtinen Saxophone – Michael Monroe Synthesizer – Michael Monroe Notes Golden version. There is also normal disc version existing. First 1.000 copies were released as golden, the rest as black background color on the disc's picture side. ℗ & © 2002 Akashic Rocks Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 6 430012 030018 Barcode (String): 6430012030018 Rights Society: BIEM/n©b TEOSTO Matrix / Runout: M7F5 HANOI MANDAG Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year People Like Me (CD, ARCDS-001 Hanoi Rocks Akashic Rocks ARCDS-001 Finland 2002 Single, Enh) People Like Me (CD, EP, ARPRCD-001 Hanoi Rocks Akashic Rocks ARPRCD-001 Finland 2002 Enh, Promo) Related Music albums to People Like Me by Hanoi Rocks Michael Monroe - Man With No Eyes Hanoi Rocks - Limited Edition Interview Picture Disc The Monroe Brothers - The Monroe Brothers Hanoi Rocks - All Those Wasted Years Hanoi Rocks - Street Poetry Michael Monroe - Whatcha Want West Monroe - West Monroe Hanoi Rocks - Previously Unreleased Hanoi Rocks - Back In Yer Face Hanoi Rocks - Bangkok Shocks, Saigon Shakes, Hanoi Rocks. -

Total Tracks Number: 1108 Total Tracks Length: 76:17:23 Total Tracks Size: 6.7 GB

Total tracks number: 1108 Total tracks length: 76:17:23 Total tracks size: 6.7 GB # Artist Title Length 01 00:00 02 2 Skinnee J's Riot Nrrrd 03:57 03 311 All Mixed Up 03:00 04 311 Amber 03:28 05 311 Beautiful Disaster 04:01 06 311 Come Original 03:42 07 311 Do You Right 04:17 08 311 Don't Stay Home 02:43 09 311 Down 02:52 10 311 Flowing 03:13 11 311 Transistor 03:02 12 311 You Wouldnt Believe 03:40 13 A New Found Glory Hit Or Miss 03:24 14 A Perfect Circle 3 Libras 03:35 15 A Perfect Circle Judith 04:03 16 A Perfect Circle The Hollow 02:55 17 AC/DC Back In Black 04:15 18 AC/DC What Do You Do for Money Honey 03:35 19 Acdc Back In Black 04:14 20 Acdc Highway To Hell 03:27 21 Acdc You Shook Me All Night Long 03:31 22 Adema Giving In 04:34 23 Adema The Way You Like It 03:39 24 Aerosmith Cryin' 05:08 25 Aerosmith Sweet Emotion 05:08 26 Aerosmith Walk This Way 03:39 27 Afi Days Of The Phoenix 03:27 28 Afroman Because I Got High 05:10 29 Alanis Morissette Ironic 03:49 30 Alanis Morissette You Learn 03:55 31 Alanis Morissette You Oughta Know 04:09 32 Alaniss Morrisete Hand In My Pocket 03:41 33 Alice Cooper School's Out 03:30 34 Alice In Chains Again 04:04 35 Alice In Chains Angry Chair 04:47 36 Alice In Chains Don't Follow 04:21 37 Alice In Chains Down In A Hole 05:37 38 Alice In Chains Got Me Wrong 04:11 39 Alice In Chains Grind 04:44 40 Alice In Chains Heaven Beside You 05:27 41 Alice In Chains I Stay Away 04:14 42 Alice In Chains Man In The Box 04:46 43 Alice In Chains No Excuses 04:15 44 Alice In Chains Nutshell 04:19 45 Alice In Chains Over Now 07:03 46 Alice In Chains Rooster 06:15 47 Alice In Chains Sea Of Sorrow 05:49 48 Alice In Chains Them Bones 02:29 49 Alice in Chains Would? 03:28 50 Alice In Chains Would 03:26 51 Alien Ant Farm Movies 03:15 52 Alien Ant Farm Smooth Criminal 03:41 53 American Hifi Flavor Of The Week 03:12 54 Andrew W.K. -

Artist Song Weird Al Yankovic My Own Eyes .38 Special Caught up in You .38 Special Hold on Loosely 3 Doors Down Here Without

Artist Song Weird Al Yankovic My Own Eyes .38 Special Caught Up in You .38 Special Hold On Loosely 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down When You're Young 30 Seconds to Mars Attack 30 Seconds to Mars Closer to the Edge 30 Seconds to Mars The Kill 30 Seconds to Mars Kings and Queens 30 Seconds to Mars This is War 311 Amber 311 Beautiful Disaster 311 Down 4 Non Blondes What's Up? 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect The 88 Sons and Daughters a-ha Take on Me Abnormality Visions AC/DC Back in Black (Live) AC/DC Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap (Live) AC/DC Fire Your Guns (Live) AC/DC For Those About to Rock (We Salute You) (Live) AC/DC Heatseeker (Live) AC/DC Hell Ain't a Bad Place to Be (Live) AC/DC Hells Bells (Live) AC/DC Highway to Hell (Live) AC/DC The Jack (Live) AC/DC Moneytalks (Live) AC/DC Shoot to Thrill (Live) AC/DC T.N.T. (Live) AC/DC Thunderstruck (Live) AC/DC Whole Lotta Rosie (Live) AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long (Live) Ace Frehley Outer Space Ace of Base The Sign The Acro-Brats Day Late, Dollar Short The Acro-Brats Hair Trigger Aerosmith Angel Aerosmith Back in the Saddle Aerosmith Crazy Aerosmith Cryin' Aerosmith Dream On (Live) Aerosmith Dude (Looks Like a Lady) Aerosmith Eat the Rich Aerosmith I Don't Want to Miss a Thing Aerosmith Janie's Got a Gun Aerosmith Legendary Child Aerosmith Livin' On the Edge Aerosmith Love in an Elevator Aerosmith Lover Alot Aerosmith Rag Doll Aerosmith Rats in the Cellar Aerosmith Seasons of Wither Aerosmith Sweet Emotion Aerosmith Toys in the Attic Aerosmith Train Kept A Rollin' Aerosmith Walk This Way AFI Beautiful Thieves AFI End Transmission AFI Girl's Not Grey AFI The Leaving Song, Pt. -

Lita Ford and Doro Interviewed Inside Explores the Brightest Void and the Shadow Self

COMES WITH 78 FREE SONGS AND BONUS INTERVIEWS! Issue 75 £5.99 SUMMER Jul-Sep 2016 9 771754 958015 75> EXPLORES THE BRIGHTEST VOID AND THE SHADOW SELF LITA FORD AND DORO INTERVIEWED INSIDE Plus: Blues Pills, Scorpion Child, Witness PAUL GILBERT F DARE F FROST* F JOE LYNN TURNER THE MUSIC IS OUT THERE... FIREWORKS MAGAZINE PRESENTS 78 FREE SONGS WITH ISSUE #75! GROUP ONE: MELODIC HARD 22. Maessorr Structorr - Lonely Mariner 42. Axon-Neuron - Erasure 61. Zark - Lord Rat ROCK/AOR From the album: Rise At Fall From the album: Metamorphosis From the album: Tales of the Expected www.maessorrstructorr.com www.axonneuron.com www.facebook.com/zarkbanduk 1. Lotta Lené - Souls From the single: Souls 23. 21st Century Fugitives - Losing Time 43. Dimh Project - Wolves In The 62. Dejanira - Birth of the www.lottalene.com From the album: Losing Time Streets Unconquerable Sun www.facebook. From the album: Victim & Maker From the album: Behind The Scenes 2. Tarja - No Bitter End com/21stCenturyFugitives www.facebook.com/dimhproject www.dejanira.org From the album: The Brightest Void www.tarjaturunen.com 24. Darkness Light - Long Ago 44. Mercutio - Shed Your Skin 63. Sfyrokalymnon - Son of Sin From the album: Living With The Danger From the album: Back To Nowhere From the album: The Sign Of Concrete 3. Grandhour - All In Or Nothing http://darknesslight.de Mercutio.me Creation From the album: Bombs & Bullets www.sfyrokalymnon.com www.grandhourband.com GROUP TWO: 70s RETRO ROCK/ 45. Medusa - Queima PSYCHEDELIC/BLUES/SOUTHERN From the album: Monstrologia (Lado A) 64. Chaosmic - Forever Feast 4. -

Hanoi Rocks Hanoi Rocks Mp3, Flac, Wma

Hanoi Rocks Hanoi Rocks mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Hanoi Rocks Country: Finland Released: 2001 Style: Glam MP3 version RAR size: 1102 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1386 mb WMA version RAR size: 1205 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 311 Other Formats: MP3 VQF ADX DMF MPC APE MOD Tracklist A. Lost In The City 1-1 –Hanoi Rocks I Want You 1-2 –Hanoi Rocks Kill City Kills (Namilo Remix) 1-3 –Hanoi Rocks Tragedy 1-4 –Hanoi Rocks Café Avenue (Original Version) 1-5 –Hanoi Rocks Stop Cryin' 1-6 –Hanoi Rocks 11th Street Kids 1-7 –Hanoi Rocks Village Girl 1-8 –Hanoi Rocks Cheyenne 1-9 –Hanoi Rocks Malibu Nightmare 1-10 –Hanoi Rocks Do The Duck 1-11 –Hanoi Rocks Love's An Injection (Demo) 1-12 –Hanoi Rocks Desperados 1-13 –Hanoi Rocks Devil Woman 1-14 –Hanoi Rocks Dead By X-Mas 1-15 –Hanoi Rocks Don't Follow Me 1-16 –Hanoi Rocks No Law Or Order 1-17 –Hanoi Rocks Mc Baby 1-18 –Hanoi Rocks Suberian Theme (Instrumental) 1-19 –Hanoi Rocks Fallen Star B. Million Miles Away 2-1 –Hanoi Rocks Self Destruction Blues 2-2 –Hanoi Rocks In The Year 79 / It's Too Late 2-3 –Hanoi Rocks Problem Child 2-4 –Hanoi Rocks Hometown Breakdown 2-5 –Hanoi Rocks Rebel On The Run 2-6 –Hanoi Rocks Back To Mystery City 2-7 –Hanoi Rocks Tooting Bec Wrecked 2-8 –Hanoi Rocks Until I Get You 2-9 –Hanoi Rocks Lick Summer Love 2-10 –Hanoi Rocks Never Get Enough (Demo) 2-11 –Hanoi Rocks High School 2-12 –Hanoi Rocks Two Steps From The Move 2-13 –Hanoi Rocks Up Around The Bend 2-14 –Hanoi Rocks Don't You Ever Leave Me 2-15 –Hanoi Rocks Million Miles Away 2-16 –Hanoi Rocks Underwater World (Edit) 2-17 –Hanoi Rocks Shakes 2-18 –Hanoi Rocks Boulevard Of Broken Dreams 2-19 –Hanoi Rocks Magic Carpet Ride C.