Multi-Disciplinary Study, Responsible Policy-Making, and Problem-Based Learning in Honors Courses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marmion Academy Class of 2013

Marmion Academy Class of 2013 The following students, having completed the requirements prescribed by the administrative board, are hereby declared graduates of Marmion Academy: Eric S. Anderson Recipient President’s Award for Academic Excellence Awarded Scholarships from Ball State University, Iowa State University Member Marmion Chapter National Honor Society Will Attend Ball State University Javier Andujar, Jr. Recipient President’s Award for Academic Excellence Awarded Scholarships from DePaul University Member Marmion Chapter National Honor Society Will Attend DePaul University Colin P. Angeles Named Illinois State Scholar Awarded Scholarships from Loyola University Chicago Will Attend Loyola University Chicato Alexander L. Arenkill Recipient President’s Award for Academic Excellence Awarded Chick Evans Full Tuition Scholarship, Scholarship from University of Dayton Member Marmion Chapter National Honor Society Will Attend Miami University of Ohio Daniel A. Arzola Will Attend Waubonsee Community College Patrick J. Bakala Awarded Scholarships from Ave Maria University, Monmouth College, St. Benedict & St. John Will Attend St. Benedict & St. John David C. Beane II Awarded Scholarships from Augustana College, Montana State University, Southern Illinois University, St. Ambrose University, University of Missouri Will Attend Augustana College Michael B. Bicknell Named Illinois State Scholar Recipient President’s Award for Academic Excellence Awarded Scholarships from Butler University, DePaul University, Holy Cross College, Marquette University, Miami University of Ohio, Purdue University, Ripon College, University of Dayton, University of Wisconsin Whitewater Member Marmion Chapter National Honor Society Will Attend Holy Cross College Kory A. Blair Awarded Scholarships to Eastern Illinois University, Western Illinois University Will Attend Western Illinois University Austin J. Bohr Will Attend Indiana University Connor L. -

Dr. Michael Bennett-Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE MICHAEL I. J. BENNETT EDUCATION: 1988 Ph.D., The University of Chicago, School of Social Service Administration (SSA) – field of study: community organization and economic development 1972 M.A., The University of Chicago (SSA) – field of study: community organization and economic development 1968 B.A., Kent State University, Kent, Ohio – major: sociology ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS: 2014-2016 Interim Chair, Department of Sociology, DePaul Univ. 2005- Associate Professor, Department of Sociology, DePaul University, Chicago 1997-2005 Assistant Professor, DePaul University 1990−1997 Assistant Professor, Jane Addams College of Social Work, University of Illinois at Chicago 1990−1997 Assistant Professor, College of Urban Planning and Public Affairs, University of Illinois at Chicago; 1992 Visiting Faculty, The University of Witswatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa 1996- Faculty, Northwestern University, Asset-Based Community Development Institute, Evanston, Ill. 1989−1990 Lecturer, The University of Chicago, School of Social Service Administration, Chicago 1979−1989 Instructor, Columbia College, Chicago 1977−1980 Adjunct Faculty, The Associated Colleges of the Midwest, Urban Studies Program, Chicago 1977−1978 Community Professor, Governor’s State University, University Park, Ill. 1974−1975 Guest Lecturer, Curriculum Consultant, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces 1969−1970 Instructor, Kent State University, Dept. of Sociology and Anthropology 1969−1970 Lecturer, Case Western Reserve University, Leadership Development Program, Cleveland 1969 Lecturer and Practicum Supervisor, Kent State University, Dept. of Guidance and Counseling ADMINISTRATIVE APPOINTMENTS: 1997−2008 Executive Director, The Monsignor John J. Egan Urban Center, DePaul University 1986−1994 Vice President, Shorebank Corp./South Shore Bank, Chicago, Vice President, Arkansas Enterprise Group, Arkadelphia, Ark. (1993-1994, affiliated with Shorebank Corp. -

Cary Martin Shelby

Cary Martin Shelby Associate Professor of Law DePaul University College of Law 25 East Jackson Boulevard Chicago, Illinois 60604 Email: [email protected] _________________________________________________________________________________________ ACADEMIC EXPERIENCE DePaul University College of Law Chicago, IL Associate Professor of Law (tenure granted in June 2017) . Courses Taught: Business Organizations, Securities Regulation, and Investment Company Regulation . Honors and Awards: DePaul University Excellence in Teaching Award (Fall 2018), DePaul College of Law Excellence in Teaching Award (Spring 2016), Black Law Student’s Association Outstanding Faculty Member Award (Fall 2012) . Committees: Diversity & Inclusion Committee (Chair, Spring 2018-present), Contingent Faculty Committee (Fall 2018-present), Readmissions Committee (Fall 2016-present), Admissions Committee (Fall 2015 – present), Faculty Council Alternate (Fall 2014–Spring 2018), Business Programs Committee (Fall 2013- present), Term Faculty Review Committee (Fall 2016), Dean Search Committee (Spring 2015), Continuing and Professional Education Advisory Committee (Fall 2014-Spring 2017), Competitions Policy Committee (Fall 2014), Career Services Advisory Committee (Fall 2014–Fall 2015), 3YP Advisory Committee (Fall 2014–Fall 2015), Pro Bono Committee (Fall 2013–Fall 2014), Technology Committee (Fall 2012–Fall 2015), Appointments Committee (Fall 2013) . Faculty Advisor: DePaul Business and Commercial Law Journal (Fall 2016-present), Black Law Student’s Association (Fall 2012–present) -

Student Life and Campus Culture at Depaul

CHAPTER FIVE STUDENT LIFE AND CAMPUS CULTURE AT DEPAUL A Hundred Year History John 1. Rury hroughout DePaul's history, its students have contributed to the institution's distinctive character. Since 1898, as the university has changed and the campus has grown, a vibrant student culture has evolved. This was hardly unique to DePaul. In many respects, the university's students have reflected national trends in their activities and interests. But as an urban institution, DePaul's location and programs have affected the character of its students and their activities. Historically, Chicago has been a city of immigrants, and over the years DePaul has served the city's principal immigrant groups. It has ministered to Chicago's Roman Catholic popula tion, to be sure, but it has also provided educational opportunities for others. As constituents of an urban university, DePaul's students have reflected the diversity and vitality one would expect of a major Chicago institution of higher learning. This is an important part of the university's heritage. In coming together at DePaul, these students created a distinctive social world of their own that changed over time, often mirroring broader tendencies in student life. Still, certain features of the DePaul student experience were quite durable and helped to define an institu tional identity. While in many respects its students were similar to their counterparts at other institutions, there were aspects of life at DePaul that were unique. In part this was simply structural. Campus life at DePaul has long been divided between its downtown and uptown (or Lincoln Park) locations, with each site acquiring its own atmosphere. -

Academic Partnerships 1

Academic Partnerships 1 ACADEMIC PARTNERSHIPS Rush University In conjunction with the Department of Health Systems Management in DePaul University has entered into a variety of relationships with other the College of Health Sciences at Rush University Medical Center, the educational institutions to provide enhanced learning opportunities for Kellstadt Graduate School of Business of the College of Commerce offers students. a joint MBA/MS (Master of Science in Health Systems Management) degree program. American University in Paris DePaul and The American University of Paris (AUP) are partnering to Truman College, City Colleges of Chicago offer an innovative two-year program leading to an MBA from DePaul’s Through an agreement with the City Colleges of Chicago, students may Kellstadt Graduate School of Business and a M.A. in Cross-cultural and complete their first years in college at Truman College, then seamlessly Sustainable Business from AUP. transfer their credits towards a DePaul undergraduate degree through the School for New Learning. Catholic Theological Union With permission, upper-level students in Catholic Studies and Religious Wright College, City Colleges of Chicago Studies may elect to complete courses at the Catholic Theological Union. Through an agreement with the City Colleges of Chicago, students may complete their first years in college at Wright College, then seamlessly Illinois Institute of Technology transfer their credits towards a DePaul undergraduate degree through the School for New Learning. Through a five-year joint program between DePaul and the Illinois Institute of Technology, students may earn a degree in physics from DePaul and degree in engineering from IIT, with a concentration in Study Abroad Opportunities Mechanical, Aerospace, Electrical, or Computer Engineering. -

Depaul University

DePaul University Office of Financial Aid At DePaul Central Steps to Confirm Citizenship Status DePaul Central Locations: DePaul Center, Suite 9100 Schmitt Academic Center, Suite 101 1 East Jackson Boulevard 2320 North Kenmore Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60604 Chicago, Illinois 60614 Ph: (312) 362-8610 | Secure document upload: wdat.is.depaul.edu/FAUpload/default.aspx To protect your personal information, please do not email documents. Steps to provide documentation of your citizenship: If your citizenship status was not confirmed by the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) of the Department of Homeland Security and/or Social Security Administration when you completed your FAFSA, you will need to submit legible copies of your original citizenship documentation to the Office of Financial aid at DePaul Central. These documents will be reviewed by our Verification team. DePaul Central’s business operations are currently being conducted remotely. Our office is available to assist you on your next steps to providing your citizenship verification documents listed below. Financial aid funds will not be released until a student submits legible citizenship documents which are deemed to meet the verification requirements. Upon submitting your documents to the secure document upload, be sure to contact our office first on your next steps, before traveling to our campus locations. Submit to our office, legible copies of your original documents listed below: • Your signed Certificate of Naturalization; or • Your signed Certificate -

Chicago Infrastructure Trust 312-809-8080 Confidential

Housing Action Illinois May 5, 2015 Presented By Charisse Conanan Johnson, CFA [email protected] Chicago Infrastructure Trust 312-809-8080 Confidential 1 Mission To assist the people of the City of Chicago, the City government , its sister agencies and private industry in providing alterna8ve, innova8ve financing and project delivery op8ons for transforma8ve infrastructure projects Energy Transportation Development Telecommunications 2 Our Approach Risk transfer Off-credit, Budget Neutral off-balance sheet Self-funding projects Underappreciated assets 3 Housing Mission Statement Create a self-sustaining neighborhood revitalization solution by developing new market-rate housing for Chicago’s underserved communities Ulmately, we improve the human condion 4 Project catalyst and inial findings • Shortage of Chicago’s market-rate housing that is truly aainable for underserved communies: – Meet the income levels of the neighborhoods (Southside and Westside) – Disabled/fixed income residents – Transi7oners: new home buyers, recent college grads, re7rees – Chicago Housing Authority wai7ng list (40,000) • Chicago owns over 15,000 vacant lots 5 Proposed sustainable soluon • Innovave cost model in range of $100k to $200k • Secure packaged mortgage and short-term construc7on financing for project • Execute on proof-of-concept for long-term feasibility • Create mix-shiQ of housing units – Owners and Renters 6 Appeal to clustered vacant lots 1,455 Parcels Considered “Most Desirable” • Demand-based analysis iden7fied 1,455 available parcels that would -

Catholic Theological Union - Project Summary

Catholic Theological Union - Project Summary Project name and key objectives: Name: Theological School Initiative to Address Economic Challenges Facing Future Ministers 1. Gather information about the economic status of our graduates and current students 2. Improve institutional strategies and practices concerning financial aid and financial counseling 3. Promote financial literacy and economic well-being for students and graduates 4. Mobilize and expand our key partnerships to help provide financial support and employment opportunities for our students and graduates The most significant activities concerning our project: The current student/alumni surveys will be used to inform our process going forward. The surveys have helped us to gather information regarding the economic status of our students/alumni; it has also been instrumental in gathering information regarding current and past employment, cost of education, debt levels, and preparedness for employment in the ministerial field. The surveys provide material for our focus groups and will assess needs for future strategies, practices, and programming. The Ministry Showcase is our yearly event that provides our students, community organizations and the greater community an environment to share information, resources and develop relationships. The hope is that the program will allow greater prospects for internships, field education, and future positions. It provides us an opportunity to develop new relationships while strengthening existing ones. It has provided us the chance to work on key partnerships in the hopes of assisting our students. Important resources: One of the most important resources we have discovered is the students. Everyone working with survey development was surprised at the amount of feedback from our student body. -

Class of 2019

Photo by Phillips Mitchell Class of Student Government Officers 2019 Story Tepper, Student Government President ◊ 73 seniors will enroll in 41 different colleges in 16 different states Lauren Carter, Student Government Vice President ◊ 81% of seniors received merit scholarships, totaling over $10 million in Cassidy Hook, Student Government Secretary college-sponsored, four-year scholarships Wick Hallos, Senior Class President ◊ $138,000 average scholarship per student Nell Adkins, Senior Class Vice President Jay Rutherford, Senior Class Secretary/Treasurer ◊ 74% of the senior class completed one or more AP examinations ◊ 3 National Merit Finalists; 1 National Merit Commended Scholar Honor Council Nell Adkins ◊ 3 seniors will participate in intercollegiate athletics Wick Hallos, co-chair ◊ 56% of seniors scored 28 or above on the ACT; 41% of the class scored Missy Hill, co-chair 30 or above Sara Tahanasab, secretary Class of 2019 College Acceptances & Choices (in bold) American University Eastern Kentucky University Northern Kentucky University University of Dayton Appalachian State University Eckerd College Northern Ohio University University of Denver Arizona State University Elon University Ohio State University University of Florida Auburn University Emory and Henry College Oklahoma State University University of Georgia Babson College Florida Atlantic University Otterbein University University of Illinois Baylor University Florida State University Palm Beach Atlantic University University of Kansas Bellarmine University Fordham University -

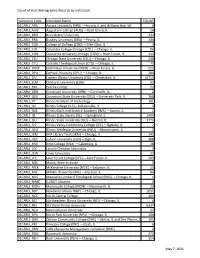

Count of Host Bibliographic Records by Institution

Count of Host Bibliographic Records by Institution Institution Code Institution Name COUNT 01CARLI_ARU Aurora University (ARU) —Aurora, IL and Williams Bay, WI 6 01CARLI_AUG Augustana College (AUG) —Rock Island, IL 16 01CARLI_BEN Benedictine University 332 01CARLI_BRA Bradley University (BRA) —Peoria, IL 144 01CARLI_COD College of DuPage (COD) —Glen Ellyn, IL 3 01CARLI_COL Columbia College Chicago (COL) —Chicago, IL 86 01CARLI_CON Concordia University Chicago (CON) —River Forest, IL 133 01CARLI_CSU Chicago State University (CSU) —Chicago, IL 348 01CARLI_CTU Catholic Theological Union (CTU) —Chicago, IL 79 01CARLI_DOM Dominican University (DOM) —River Forest, IL 212 01CARLI_DPU DePaul University (DPU) —Chicago, IL 280 01CARLI_EIU Eastern Illinois University (EIU) —Charleston, IL 16713 01CARLI_ELM Elmhurst University (ELM) 92 01CARLI_ERK Eureka College 22 01CARLI_GRN Greenville University (GRN) —Greenville, IL 2 01CARLI_GSU Governors State University (GSU) —University Park, IL 160 01CARLI_IIT Illinois Institute of Technology 191 01CARLI_ILC Illinois College (ILC)—Jacksonville, IL 3 01CARLI_IMS Illinois Math and Science Academy (IMS) —Aurora, IL 1 01CARLI_ISL Illinois State Library (ISL) —Springfield, IL 1495 01CARLI_ISU Illinois State University (ISU) —Normal, IL 3775 01CARLI_IVC Illinois Valley Community College (IVC) —Oglesby, IL 7 01CARLI_IWU Illinois Wesleyan University (IWU) —Bloomington, IL 3 01CARLI_JKM JKM Library Trust (JKM) —Chicago, IL 345 01CARLI_JUD Judson University (JUD) —Elgin, IL 388 01CARLI_KNX Knox College (KNX) —Galesburg, -

2004 Data Book Illinois Student Assistance Commission TABLE of CONTENTS

2004 Data Book Illinois Student Assistance Commission TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................... v PART ONE - ISAC APPROPRIATION HISTORY .................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Table 1.0 Appropriation History, FY1980-FY2004 ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 Table 1.1 Summary of FY2004 Program Expenditures, Recipients, and Loan Guarantees ............................................................................................ 5 PART TWO - MONETARY AWARD PROGRAM .................................................................................................................................................................. 7 Table 2.0a Historical Awards (total applications, announced eligible, enrolled) and Payout Summary, FY1990-FY2004 ............................................ 9 Table 2.0b FY2004 Monetary Award Program Formula ............................................................................................................................................... 10 Sector Statistics Table 2.1 Historical Enrolled Awards and Payout Summary by Sector, FY1980-FY2004 ........................................................................................... -

N I Come to Depaul from the University of Chicago, Where I Chair of Biological Sciences Performed Research on Alzheimer’S Disease As a Postdoc After Receiving My Ph.D

THE NICHE V1 #2 DEPAUL UNIVERSITY | DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES FROM THE DESK OF THE CHAIR There have been a number of exciting changes that have occurred in the past year for the Department of Biological Sciences. One of the most significant changes has been the move to the College of Science and Health (CSH). This new college will include programs in biology, chemistry, physics, nursing, psychology, environmental science, mathematics and health sciences. CSH represents the tenth college/ school here at DePaul University. With over 750 majors, the Department of Biological Sciences is the second largest program in the new college, trailing only psychology. Two departmental faculty members have taken on leadership roles in CSH. Phillip Funk, Ph.D., is serving as the associate dean for external relations and Margaret Silliker, Ph.D., is serving as associate dean for graduate studies. The second major change is the department’s involvement in the new (fall 2011) degree program in health sciences. Several faculty in the department contributed to the development of this interdisciplinary program and several of our core courses will be integral to the health sciences curriculum. Dorothy Kozlowski, Ph.D., a biological sciences faculty member, is currently serving as the chair of the new Department of Health Sciences. Our faculty are looking forward to playing a significant role in shaping the direction of the new college and contributing to the program and curriculum innovations that will benefit those DePaul students interested in the growing career opportunities in the science and healthcare fields. Over the past five years, enrollments in courses offered through the Department of Biological Sciences have experienced phenomenal growth.