Flaubert: from Dervish to Saint

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kazuhiko YAMAGUCHI

Journal of Educational Research, Shinshu University, No. 4 (1998) 123 A Portrait of the Author of Vathek Kazuhiko YAMAGUCHI William Beckford (1760-1844) has generally been reputed to be one of the most notable of the whole company of Eng}ish eccentrics. In a conventional age and born to the vast wealth that observes conventionality his extravagance lay in his unconventional creed and frequently eccentric behaviour. No doubt he was often misconstrued. People spread gossip concerning misspent opportunities, great possession squandered, the lack of a sense of responsibility, and an entirely wasted life spent upon follies and hobbies. But he was indifferent to public opinion. Until the end of his long and singular career he persistently refused to conform to the pattern of his class, remaining staunchly uncom- promising towards the conventional norms of Georgian society. As a consequence one serious charge after another was brought against hirn, probably on no stronger founda- tion than the undoubted fact of his deviation from the usual type of the English gentle- mall. Yet this surely is not all he was. There is more to be said for Beckford even while, in part, admitting the justice of the calumnies that have been heaped upon his unpredict- able personality. He was much more than an eccentric millionaire: rather a man of many accornplishments and exceptional culture. To begin with he possessed the attributes of the universal man. He was trilingual: as fluent in French and Italian as in his native English, besides speaking Spanish, German, Portuguese, Persian and Arabic. He could judge events and their causes as a true cosmopolitan. -

University of Alberta Qasim's Short Stories: .4N Esample of Arnbic

University of Alberta Qasim's Short Stories: .4n Esample of Arnbic SupernaturaUGhost/Horror Story Sabah H Alsowaifan O -4 thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requiremrnts for the degree of Doctor of philosophy Comparative Literature Department of Comparative Literature, Religion, and Filmli\fedia Studies Edmonton, Alberta Spnng 200 1 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 191 ,,a& du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 WeUington Street 395, rue Wellington Onawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON KlA ON4 CaMda Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Libwof Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, ban, distniute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in micloform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/fi.lm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Dedica tion To my father and mother. To my supervisor, Dr. Milan V. Dimic. To Mr. Faisal Yousef Al Marzoq. To the Commercial Bank of Kuwait. To Kuwait University. Abstract This dissertation focuses on an Arabic wnter of short stories, Qasirn Khadir Qasim. -

Lovecraft HP

History of the Necronomicon by H.P. Lovecraft (1927) (There has been some difficulty over the date of this essay. Most give the date as 1936, following the Laney-Evans (1943) bibliography entry for the pamphlet version produced by the Rebel Press. This date, as can easily be ascertained from the fact that this was a "Limited Memorial Edition", is spurious (Lovecraft died in 1937); in fact, it dates to 1938. The correct date of 1927 comes from the final draft of the essay, which appears on a letter addressed to Clark Ashton Smith ("To the Curator of the Vaults of Yoh-Vombis, with the Concoctor's [?] Comments"). The letter is dated April 27, 1927 and was apparently kept by Lovecraft to circulate as needed.) - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Original title Al Azif -- azif being the word used by Arabs to designate that nocturnal sound (made by insects) suppos'd to be the howling of daemons. Composed by Abdul Alhazred, a mad poet of Sana, in Yemen, who is said to have flourished during the period of the Ommiade caliphs, circa 700 A.D. He visited the ruins of Babylon and the subterranean secrets of Memphis and spent ten years alone in the great southern desert of Arabia -- the Roba el Khaliyeh or "Empty Space" of the ancients -- and "Dahna" or "Crimson" desert of the modern Arabs, which is held to be inhabited by protective evil spirits and monsters of death. Of this desert many strange and unbelievable marvels are told by those who pretend to have penetrated it. In his last years Alhazred dwelt in Damascus, where the Necronomicon (Al Azif) was written, and of his final death or disappearance (738 A.D.) many terrible and conflicting things are told. -

“An Imperialism of the Imagination”: Muslim Characters and Western Authors in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries Robin K

Student Publications Student Scholarship Fall 2013 “An Imperialism of the Imagination”: Muslim Characters and Western Authors in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries Robin K. Miller Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, and the Religion Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Miller, Robin K., "“An Imperialism of the Imagination”: Muslim Characters and Western Authors in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries" (2013). Student Publications. 197. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/197 This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/ 197 This open access student research paper is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “An Imperialism of the Imagination”: Muslim Characters and Western Authors in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries Abstract This paper specifically discusses the cultural attitudes that made writing fully realized Muslim characters problematic for Western authors during the 19th and 20th centuries and also how, through their writing, certain authors perpetuated these attitudes. The discussed authors and works include William Beckford's Vathek, Lord Byron's poem “The iG aour,” multiple short stories from the periodical collection Oriental Stories, one of Hergé's installments of The Adventures of Tintin, and E.M. -

Anxiety of Motherhood in Vathek Abigail J

The Onyx Review: The Interdisciplinary Research Journal © 2017 Center for Writing and Speaking 2017, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 1–6 Agnes Scott College Anxiety of Motherhood in Vathek Abigail J. Biles Agnes Scott College In William Beckford’s Vathek, we encounter one of the only living and active mothers in the Gothic genre. Carathis, the mother of the titular character and caliph, exercises her maternal control in pursuit of the survival as well as fame of her offspring, but is led terribly astray, securing for herself and her child an eternity of damnation. Revealing eighteenth-century concerns about the role of mothers, and eerily anticipating Freud, Vathek reveals cultural anxieties about the power of the mother over the child, especially when the mother has her own desires and ambitions. In her hellish end, Carathis illustrates the fate of women who seek more than society is willing to allow them. In conclusion, it appears that whether she lives or she dies, whether she is present or absent, whether she is selfish or selfless, the Gothic mother will bear the weight of the father, and the patriarchy, and his ruthless desire to have sons and money, and if she dare, as Carathis dared, to have her own ambition and her own son, she will fail and she will only have her mother to blame. n a footnote on “On The concerns about the mother consuming the Reproduction of Mothering: A child, like a reverse birth, when the child I Methodological Debate,” the editors fails to separate from its mother in the early pose a thought provoking idea: stages of development. -

TURKISH TALES”: an INTRODUCTION Peter Cochran

1 BYRON’S “TURKISH TALES”: AN INTRODUCTION Peter Cochran Sequence of composition and publication These six poems consolidated Byron’s fame – or notoriety – throughout the world, after the publication of Childe Harold I and II in March 1812. The Giaour was started in London between September 1812 and March 1813, first published by John Murray in late March 1813, and finally completed December 1813, after having, in Byron’s words, “lengthened its rattles” (BLJ III 100) from 407 lines in the first draft to 1334 lines in the twelfth edition. The Bride of Abydos was drafted in London in the first week of November 1813, was fair- copied by November 11th, and was first published by Murray on December 2nd 1813, almost simultaneous with the last edition of The Giaour . The Corsair was drafted mostly at Six Mile Bottom, the home of Byron’s half-sister Augusta Leigh, near Newmarket. Canto I was started on December 18th 1813, and Canto II on December 22nd 1813. The fair copy was started between December 27th and 31st 1813, and final proof corrections were made on January 16th or 17th 1814; the poem was first published by Murray on February 1st 1814. The first canto of Lara was started in London on May 15th 1814, and the draft of Canto 2 started June 5th of the same year, and finished on June 12th. The poem was fair-copied between June 14th and 23rd, and first published by Murray, anonymously, with Samuel Rogers’ Jacqueline: a Tale, shortly after August 5th 1814. The Siege of Corinth is probably based on much earlier material. -

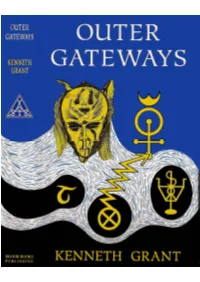

Outer Gateways

1. Invocation by Hamsa OUTER GATEWAYS Kenneth Grant SCOOB BOOKS PUBLISHING LONDON Copyright © Kenneth Grant 1994 First Published in 1994 by SKOOB BOOKS PUBLISHING Skoob esoterica series lla-17 Sicilian Avenue Southampton Row London WC1A 2QH Series editor: Christopher Johnson All rights reserved ISBN 1 871438 12 8 Printed by Hillman Printers (Frome) Ltd Contents Introduction 1 The Primal Grimoire 2 Tutulu 3 The Unfamiliar Spirit 4 The Double Voice Behind Liber AL 5 The Madhyamaka & Crowley 6 The Fourth Power of the Sphinx 7 Magical Significance of Yezidic Symbolism 8 The Mirroracle 9 Ufologicks & the Rite of Mithra 10 Typhonian Implicits of Arunachala 11 Apects of Dream Control 12 Creative Gematria 13 Wisdom of S'lba 14 Mystical Gnosis of S'lba 15 Magical Formulae of S'lba 16 Qabalahs of S'lba - I 17 Qabalahs of S'lba - II Glossary Bibliography Index Illustrations Plate 1 Invocation by Hamsa frontispiece 2 Cthulhu by H.A.McNeill II 3 The Magician (Frieda Harris / Aleister Crowley) 4 The Chariot (Frieda Harris / Aleister Crowley) 5 The Sabbatic Candlesticks and Satyr 6 Black Eagle by Austin Osman Spare 7 Seal of Zos Kia Cultus by Steffi Grant 8 Desmodus by Kenneth Grant 9 “Thirst” (Steffi Grant / Aleister Crowley) 10 Horus byy H.A.McNeill II 11 Yantra of Kali 12 Formula of Arrivism by Austin Osman Spare 13 The Self’s Vision of Enlightenment by Austin Osman Spare 14 The Arms of Dunwich The Eye of Set The Seal of Aossic 15 Ilyarun by Steffi Grant 16 Evocation by Hamsa 17 Astral Marginalia (Shades of S’lba), by Kenneth Grant Line Illustrations 18 The Yantra of 31 note music (William Coates) 19 The Tree of Life To the memory of RUDOLF FRIEDMANN I can tell you how to find those who will show you the secret gateway that leads inward only, and closes fast behind the neophyte for evermore. -

Winter Quarter Course Offerings 2000

WINTER QUARTER COURSE OFFERINGS 2000 MIDDLE EAST STUDIES SLN: 6941 SISME 490 A SPECIAL TOPICS (3 Cr) HOLMES-EBER w/ANTH 469 C (SLN: 1269) JUNIORS,SENIORS,GRADS ONLY TTh 11:30-12:50 PAR 112 GENDER AND FAMILY IN MIDDLE EAST As an upper level seminar, this class will emphasize learning through comparison and discussion of a variety of readings. Topics examined will include gender and Islam, women and the family in Middle Eastern history; gender identity, space and veiling; family structure and kinship; and contemporary issues such as family law and the legal status of women, women and work, and women’s health. Students will explore the complexity of each topic through four 5-7 page response papers. Due to the need for more in-depth advanced work, graduate students will also research and present to the class a 10-15 page paper on a topic of their choice. SLN: 6942 SISME 600 INDEPENDENT STUDY (Var Cr) TO BE ARRANGED INSTRUCTOR I.D. THO 111 SLN: 6943 SISME 700 MASTERS THESIS (Var Cr) TO BE ARRANGED INSTRUCTOR I.D. THO 111 ANTHROPOLOGY SLN: 1269 ANTH 469 SPEC STUDIES ANTH (3 Cr) HOLMES-EBER OFFERED JOINTLY WITH SISME 490 A JUNIORS,SENIORS,GRADS ONLY TTh 11:30-12:50 PAR 112 GENDER AND FAMILY IN MIDDLE EAST (SEE SISME 490 A for Course Description) ARCHEOLOGY SLN: 1341 ARCHY 105 AA WORLD PREHISTORY (5 Cr) CLOSE Other Sections available MWThF 10:30-11:20 SMI 120 T 8:30-9:20 DEN 206 Prehistoric human ancestors from three million years ago: their spread from Africa and Asia into the Americas, survival during ice ages, development of civilizations. -

Manfred and Vathek

1 MANFRED AND VATHEK To Byron, William Beckford’s Vathek was ... a work ... which ... I never recur to, or read, without a renewal of gratification.1 Earlier he had written, in a note to The Giaour, line 1334, of: ... that most eastern, and ... “sublime tale”, the “Caliph Vathek”. I do not know from what source the author of that singular volume may have drawn his materials; some of his incidents are to be found in the “Bibliotheque Orientale”; but for correctness of costume, beauty of description, and power of imagination, it far surpasses all European imitations; and bears such marks of originality, that those who have visited the East will have difficulty in believing it to be more than a translation. As an Eastern tale, even Rasselas must bow before it; his “Happy Valley” will not bear a comparison with the “Hall of Eblis”.2 The influence of the novel on the poems Byron wrote immediately prior to Manfred is often pointed out.3 The standard point of reference when relating Manfred itself to Vathek is the opening stage direction of II iv, giving “Arimanes on his Throne, a Globe of Fire, surrounded by the Spirits”, which echoes unambiguously the following passage from Beckford’s book: An infinity of elders with streaming beards, and afrits in comp lete armour, had prostrated themselves before the ascent of a lofty eminence; on the top of which, upon a globe of fire, sat the formidable Eblis. His person was that of a young man, whose noble and regular features seemed to have been tarnished by malignant vapours. -

The Evolution of Modern Fantasy from Antiquarianism to the Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series

Copyrighted Material - 9781137518088 The Evolution of Modern Fantasy From Antiquarianism to the Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series Jamie Williamson Copyrighted Material - 9781137518088 Copyrighted Material - 9781137518088 the evolution of modern fantasy Copyright © Jamie Williamson, 2015. All rights reserved. First published in 2015 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN® in the United States— a division of St. Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Where this book is distributed in the UK, Europe and the rest of the world, this is by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. ISBN: 978- 1- 137- 51808- 8 Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Williamson, Jamie. The evolution of modern fantasy : from antiquarianism to the Ballantine adult fantasy series / by Jamie Williamson. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 1- 137- 51808- 8 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Fantasy literature— History and criticism. I. Title. PN56.F34W55 2015 809.3'8766— dc23 2015003219 A catalogue record of the book is available from the British Library. Design by Scribe Inc. First edition: July 2015 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Copyrighted Material - 9781137518088 Copyrighted -

Early Orientalism

Early Orientalism The history of western notions about Islam is of obvious scholarly as well as popular interest today. This book investigates Christian images of the Muslim Middle East, focusing on the period from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment, when the nature of divine as well as human power was under particularly intense debate in the West. Ivan Kalmar explores how the controversial notion of submission to ultimate authority has in the western world been discussed with reference to Islam’s alleged recommendation to obey, unquestioningly, a merciless Allah in heaven and a despotic government on earth. He discusses how Abrahamic faiths – Christianity and Judaism as much as Islam – demand devotion to a sublime power, with the faith that this power loves and cares for us, a concept that brings with it the fear that, on the contrary, this power only toys with us for its own enjoyment. For such a power, Kalmar borrows Slavoj Zizek’s term “obscene father”. He discusses how this describes exactly the western image of the Oriental despot - Allah in heaven, and the various sultans, emirs and ayatollahs on earth – and how these despotic personalities of imagined Muslim society function as a projection, from the West on to the Muslim Orient, of an existential anxiety about sublime power. Making accessible academic debates on the history of Christian perceptions of Islam and on Islam and the West, this book is an important addition to the existing literature in the areas of Islamic studies, religious history and philosophy. Ivan Kalmar is a professor at the University of Toronto. -

Representing the East in British Romantic Oriental Tales

Romantic Orientalism: Representing the East in British Romantic Oriental Tales Lord Byron in Albanian Dress (1813) ENGL 02 499: Senior Seminar Dr. Christina Solomon Spring 2021 Course Description: This course will explore how British Romantic writers depicted and engaged with the East in a variety of modes and genres—and, indeed, mixed genres and forms as a way of grappling with the “exotic” Eastern Other. Fundamentally at stake are questions of representation—and how literary production locates representation historically, socially, and culturally. The Arabian Nights first entered the European literary tradition in 1704 (French; English 1706) and has inspired continuations, adaptations, and appropriations ever since. Over the course of the eighteenth century in England, the oriental tale developed from an Enlightenment mode to a Romantic one—in many ways revising and reimagining elements drawn from The Arabian Nights. The influence of this indelible touchstone was heightened by the rise of Modern Orientalism, which, according to Edward Said, began to take shape around the beginning of the Romantic period. As globalization, empire, and nationalism all grew, British writers adopted new tactics to mediate literary encounters with the East. Below is a smattering of potential texts this course might cover; the generous list is provided to give a sense of the variety of British literary engagements with the East at this time. In fact, we might even think of the literary landscape as seemingly “colonizable” terrain; for instance, Thomas Moore was deeply jealous of Lord Byron’s copious output of oriental tales in the 1810s and feared being considered a “Byronian” and a follower, rather than a discoverer and conqueror (a problematic notion for multiple reasons).