Post-Horror Chapter 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

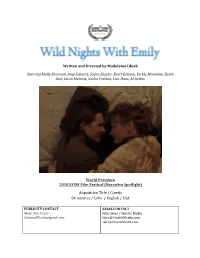

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek Starring Molly Shannon, Amy Seimetz, Susan Ziegler, Brett Gelman, Jackie Monahan, Kevin Seal, Dana Melanie, Sasha Frolova, Lisa Haas, Al Sutton World Premiere 2018 SXSW Film Festival (Narrative Spotlight) Acquisition Title / Cinetic 84 minutes / Color / English / USA PUBLICITY CONTACT SALES CONTACT Mary Ann Curto John Sloss / Cinetic Media [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE FILM PRESS MATERIALS CONTACT and FILM CONTACT: Email: [email protected] DOWNLOAD FILM STILLS ON DROPBOX/GOOGLE DRIVE: For hi-res press stills, contact [email protected] and you will be added to the Dropbox/Google folder. Put “Wild Nights with Emily Still Request” in the subject line. The OFFICIAL WEBSITE: http://wildnightswithemily.com/ For news and updates, click 'LIKE' on our FACEBOOK page: https://www.facebook.com/wildnightswithemily/ "Hilarious...an undeniably compelling romance. " —INDIEWIRE "As entertaining and thought-provoking as Dickinson’s poetry.” —THE AUSTIN CHRONICLE SYNOPSIS THE STORY SHORT SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in " Wild Nights With Emily," a dramatic comedy. The film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman. LONG SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in the dramatic comedy " Wild Nights with Emily." The poet’s persona, popularized since her death, became that of a reclusive spinster – a delicate wallflower, too sensitive for this world. This film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman (Susan Ziegler). After Emily died, a rivalry emerged when her brother's mistress (Amy Seimetz) along with editor T.W. -

What Kubrick's Kelley O'brien University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School March 2018 "He Didn't Mean It": What Kubrick's Kelley O'Brien University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation O'Brien, Kelley, ""He Didn't Mean It": What Kubrick's" (2018). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/7204 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “He Didn‟t Mean It”: What Kubrick‟s The Shining Can Teach Us About Domestic Violence by Kelley O‟Brien A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts With a concentration in Humanities Department of Humanities and Cultural Studies College Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Daniel Belgrad, Ph.D. Maria Cizmic, Ph.D. Amy Rust Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 8, 2018 Keywords: Patriarchy, Feminism, Gender Politics, Horror, American 1970s Copyright © 2018, Kelley O‟Brien Dedication I dedicate this thesis project to my mother, Terri O‟Brien. Thank you for always supporting my dreams and for your years of advocacy in the fight to end violence against women. I could not have done this without you. Acknowledgments First I‟d like to express my gratitude to my thesis advisor Dr. -

Cast Biographies RILEY KEOUGH (Christine Reade) PAUL SPARKS

Cast Biographies RILEY KEOUGH (Christine Reade) Riley Keough, 26, is one of Hollywood’s rising stars. At the age of 12, she appeared in her first campaign for Tommy Hilfiger and at the age of 15 she ignited a media firestorm when she walked the runway for Christian Dior. From a young age, Riley wanted to explore her talents within the film industry, and by the age of 19 she dedicated herself to developing her acting craft for the camera. In 2010, she made her big-screen debut as Marie Currie in The Runaways starring opposite Kristen Stewart and Dakota Fanning. People took notice; shortly thereafter, she starred alongside Orlando Bloom in The Good Doctor, directed by Lance Daly. Riley’s memorable work in the film, which premiered at the Tribeca film festival in 2010, earned her a nomination for Best Supporting Actress at the Milan International Film Festival in 2012. Riley’s talents landed her a title-lead as Jack in Bradley Rust Gray’s werewolf flick Jack and Diane. She also appeared alongside Channing Tatum and Matthew McConaughey in Magic Mike, directed by Steven Soderbergh, which grossed nearly $167 million worldwide. Further in 2011, she completed work on director Nick Cassavetes’ film Yellow, starring alongside Sienna Miller, Melanie Griffith and Ray Liota, as well as the Xan Cassavetes film Kiss of the Damned. As her camera talent evolves alongside her creative growth, so do the roles she is meant to play. Recently, she was the lead in the highly-anticipated fourth installment of director George Miller’s cult- classic Mad Max - Mad Max: Fury Road alongside a distinguished cast comprising of Tom Hardy, Charlize Theron, Zoe Kravitz and Nick Hoult. -

Extreme Art Film: Text, Paratext and DVD Culture Simon Hobbs

Extreme Art Film: Text, Paratext and DVD Culture Simon Hobbs The thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Portsmouth. September 2014 Declaration Whilst registered as a candidate for the above degree, I have not been registered for any other research award. The results and conclusions embodied in this thesis are the work of the named candidate and have not been submitted for any other academic award. Word count: 85,810 Abstract Extreme art cinema, has, in recent film scholarship, become an important area of study. Many of the existing practices are motivated by a Franco-centric lens, which ultimately defines transgressive art cinema as a new phenomenon. The thesis argues that a study of extreme art cinema needs to consider filmic production both within and beyond France. It also argues that it requires an historical analysis, and I contest the notion that extreme art cinema is a recent mode of Film production. The study considers extreme art cinema as inhabiting a space between ‘high’ and ‘low’ art forms, noting the slippage between the two often polarised industries. The study has a focus on the paratext, with an analysis of DVD extras including ‘making ofs’ and documentary featurettes, interviews with directors, and cover sleeves. This will be used to examine audience engagement with the artefacts, and the films’ position within the film market. Through a detailed assessment of the visual symbols used throughout the films’ narrative images, the thesis observes the manner in which they engage with the taste structures and pictorial templates of art and exploitation cinema. -

BFI CELEBRATES BRITISH FILM at CANNES British Entry for Cannes 2011 Official Competition We’Ve Got to Talk About Kevin Dir

London May 10 2011: For immediate release BFI CELEBRATES BRITISH FILM AT CANNES British entry for Cannes 2011 Official Competition We’ve Got to Talk About Kevin dir. Lynne Ramsay UK Film Centre supports delegates with packed events programme 320 British films for sale in the market A Clockwork Orange in Cannes Classics The UK film industry comes to Cannes celebrating the selection of Lynne Ramsay’s We Need to Talk About Kevin for the official competition line-up at this year’s festival, Duane Hopkins’s short film, Cigarette at Night, in the Directors’ Fortnight and the restoration of Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, restored by Warner Bros; in Cannes Classics. Lynne Ramsay’s We Need To Talk About Kevin starring Tilda Swinton was co-funded by the UK Film Council, whose film funding activities have now transferred to the BFI. Duane Hopkins is a director who was supported by the UK Film Council with his short Love Me and Leave Me Alone and his first feature Better Things. Actor Malcolm McDowell will be present for the screening of A Clockwork Orange. ITV Studios’ restoration of A Night to Remember will be screened in the Cinema on the Beach, complete with deckchairs. British acting talent will be seen in many films across the festival including Carey Mulligan in competition film Drive, and Tom Hiddleston & Michael Sheen in Woody Allen's opening night Midnight in Paris The UK Film Centre offers a unique range of opportunities for film professionals, with events that include Tilda Swinton, Lynne Ramsay and Luc Roeg discussing We Need to Talk About Kevin, The King’s Speech producers Iain Canning and Gareth Unwin discussing the secrets of the film’s success, BBC Film’s Christine Langan In the Spotlight and directors Nicolas Winding Refn and Shekhar Kapur in conversation. -

Siriusxm and Pandora Present Halloween at Home with Music, Talk, Comedy and Entertainment Treats for All

NEWS RELEASE SiriusXM and Pandora Present Halloween at Home with Music, Talk, Comedy and Entertainment Treats For All 10/13/2020 The world is scary enough, so have some spooky fun by streaming Halloween programming on home devices & mobile apps NEW YORK, Oct. 13, 2020 /PRNewswire/ -- SiriusXM and Pandora announced today they will feature a wide variety of exclusive Halloween-themed programming on both platforms. With traditional Halloween activities aected by the Covid-19 pandemic, SiriusXM and Pandora plan to help families and listeners nd creative and safe ways to keep the spirit alive with endless hours of music and entertainment for the whole family. Beginning on October 15, SiriusXM will air extensive programming including everything from scary stories, to haunted house-inspired sounds, to Halloween-themed playlists across SiriusXM's music, talk, comedy and entertainment channels. Pandora oers a lineup of Halloween stations and playlists for the whole family, including the newly updated Halloween Party station with Modes, and a hosted playlist by Halloween-obsessed music trio LVCRFT. All programming from SiriusXM and Pandora is available to stream online on the SiriusXM and Pandora mobile apps, and at home on a wide variety of connected devices. SiriusXM's Scream Radio channel is an annual tradition for Halloween enthusiasts, providing the ultimate bone- chilling soundtrack of creepy sound eects, traditional Halloween favorite tunes, ghost stories, spooky music from classic horror lms, and more. The limited run channel will also feature a top 50 Halloween song countdown, "The Freaky 50" and will play scary score music, sound eects, spoken word stories 24 hours a day, and will set the tone for a spooktacular haunted house vibe. -

Towards a Fifth Cinema

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sussex Research Online Towards a fifth cinema Article (Accepted Version) Kaur, Raminder and Grassilli, Mariagiulia (2019) Towards a fifth cinema. Third Text, 33 (1). pp. 1- 25. ISSN 0952-8822 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/80318/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk Towards a Fifth Cinema Raminder Kaur and Mariagiulia Grassilli Third Text article, 2018 INSERT FIGURE 1 at start of article I met a wonderful Nigerian Ph.D. -

What Are You So Scared About?: Understanding the False

What Are You So Scared About?: Understanding the False Fear Response to Horror Films Sarah Seyler HSS 490-01H Faculty Director: Dr. Jeffrey Adams April 22nd, 2019 1 When a horror movie delivers a scare to an audience member, it is able to achieve something that is entirely illogical; it has made someone scared of something that poses no threat. So what is the logic behind a horror film? What aspects make a horror movie, something that can pose no physical threat, scary? In order to solve this question, many different aspects of filmmaking in horror will be looked at, including filmmaking techniques, psychological manipulation through storytelling, and the exploration of certain cultural elements in horror films that contextualize the fears a society has. By analyzing the different aspects of horror, we can understand how and why a movie is able to override the rational side of a viewer’s brain and make them scared. We can then understand why these aspects cause the body to have a physical reaction to the false threat, and why some people respond more intensely to horror than others. The goal of any movie is to elicit some sort of emotional response in the audience observing the film, and this is no different for horror movies. However, instead of a joy or sadness response, the horror movie aims to cause an observer to feel some sort of fear -- whether that be an immediate physical fear or longer-lasting psychological distress. Scaring people may sound simple, however it is actually a pretty complex process, as the film must be logical enough for the audience to buy into, allowing them to become immersed in the movie. -

A Clockwork Orange and Stanley Kubrick’S Film Adaptations

2016-2017 A dissertation submitted to Ghent University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts – Linguistics and Literature: English & Dutch THE TRUTH BETWEEN THE LINES A Comparative Analysis of Unreliable Narration in Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange and Stanley Kubrick’s Film Adaptations Name: Isaura Vanden Berghe Student number: 01304811 Supervisor: Marco Caracciolo ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my master’s dissertation advisor Assistant Professor of English and Literary Theory, Marco Caracciolo of the Department of Literary Studies at the University of Ghent. Whenever I needed guidance or had a question about my research or writing, Prof. Caracciolo was always quick to respond, steering me in the right direction whenever he thought I needed it. Then, I must also express my very profound gratitude to my parents and to my brother for providing me with continuous encouragement and unfailing support throughout my years of study and through the process of writing and researching this dissertation. This accomplishment would not have been possible without them. Thank you. TABLE OF CONTENT INTRODUCTION 1 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK 5 THEORY OF UNRELIABLE NARRATION 5 UNRELIABLE NARRATION IN FILM 9 LOLITA 12 LOLITA: THE NOVEL (1955) 12 IN HUMBERT HUMBERT’S DEFENSE: A SUMMARY 12 UNRELIABLE NARRATION IN THE NOVEL 15 LOLITA: THE FILM (1962) 35 STANLEY KUBRICK AND ‘CINEMIZING’ THE NOVEL 35 UNRELIABLE NARRATION IN THE FILM 36 A CLOCKWORK ORANGE 47 A CLOCKWORK ORANGE: THE NOVEL (1962) 47 ALEX’S ULTRA-VIOLENT RETELLING: A SUMMARY 47 UNRELIABLE NARRATION IN THE NOVEL 50 A CLOCKWORK ORANGE: THE FILM (1972) 63 STANLEY KUBRICK’S ADAPTATION 63 UNRELIABLE NARRATION IN THE FILM 64 CONCLUSION 75 REFERENCES APPENDIX A APPENDIX B APPENDIX C INTRODUCTION In 2011, Mark Jacobs launched a campaign ad for a new fragrance of his, called ‘Oh, Lola!’1. -

The World to Come

THE WORLD TO COME Directed by Mona Fastvold *World Premiere - 2020 Venice International Film Festival - Competition* PRESS CONTACTS US Press: Emilie Spiegel, [email protected] Intl Press: Claudia Tomassini, [email protected] SYNOPSIS In this frontier romance framed by the four seasons and set against the backdrop of rugged terrain, Abigail (Katherine Waterston), a farmer’s wife, and her new neighbor Tallie (Vanessa Kirby) find themselves powerfully, irrevocably drawn to each other. As grieving Abigail tends to the needs of her taciturn husband Dyer (Casey Affleck) and Tallie bristles at the jealous control of her husband Finney (Christopher Abbot), both women are illuminated and liberated by their intense bond, filling a void in their lives they never knew existed. Director Mona Fastvold (The Sleepwalker, co-writer of CHILDHOOD OF A LEADER and VOX LUX) examines the interior lives of two women resisting constraints, giving voice to their experiences. Scripted by Jim Shepard and Ron Hansen (The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford), THE WORLD TO COME explores how isolation is overcome by the power of imagination and human connection. Q&A with Director Mona Fastvold First of all, tell me how the material came your way. It’s an interesting pairing of a novelist adapting a short story — was this a script that came to you fully formed? The script came to me from one of our producers, Whitaker Lader, who had seen my previous film. She and Casey had been developing the script with the screenwriters, Ron Hansen and Jim Shepard, for some time. I was immediately struck by it. -

Dissecting the Sundance Curse: Exploring Discrepancies Between Film Reviews by Professional and Amateur Critics

Dissecting the Sundance Curse by Lucas Buck — 27 Dissecting the Sundance Curse: Exploring Discrepancies Between Film Reviews by Professional and Amateur Critics Lucas Buck Cinema and Television Arts Elon University Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements in an undergraduate senior capstone course in communications Abstract There has been a growing discrepancy between professional-critic film reviews and audience-originating film reviews. In fact, these occurrences have become so routine, industry writers often reference a “Sundance Curse” – when a buzzy festival-circuit film bombs with the general public, commercially or critically. This study examines this inconsistency to determine which aspects of a film tend to draw the most attention from each respective type of critic. A qualitative content analysis of 20 individual reviews was conducted to determine which elements present in a film garnered the most attention from the reviewers, and whether that attention was positive, negative or neutral. This study indicates that audience film reviewers overwhelmingly focused on the “emotional response” gleaned from their movie-going experience above all other aspects of the film, whereas professional critics focused attention to more tangible – above-the-line contributions, such as direction, performances, and writing. I. Introduction As one of the most talked-about films of the 2018 Sundance Film Festival, theA24-released Hereditary became the breakout horror film of the year, opening in nearly 3,000 theaters and raking in $79 million while produced on just a $10 million production budget (Cusumano, 2018). Despite the obvious box office success, Hereditary’s word-of-mouth power seemed to have mostly been driven by glowing critical reviews, rather than by the opinion of audiences who paid to see the film. -

Between Liminality and Transgression: Experimental Voice in Avant-Garde Performance

BETWEEN LIMINALITY AND TRANSGRESSION: EXPERIMENTAL VOICE IN AVANT-GARDE PERFORMANCE _________________________________________________________________ A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theatre and Film Studies in the University of Canterbury by Emma Johnston ______________________ University of Canterbury 2014 ii Abstract This thesis explores the notion of ‘experimental voice’ in avant-garde performance, in the way it transgresses conventional forms of vocal expression as a means of both extending and enhancing the expressive capabilities of the voice, and reframing the social and political contexts in which these voices are heard. I examine these avant-garde voices in relation to three different liminal contexts in which the voice plays a central role: in ritual vocal expressions, such as Greek lament and Māori karanga, where the voice forms a bridge between the living and the dead; in electroacoustic music and film, where the voice is dissociated from its source body and can be heard to resound somewhere between human and machine; and from a psychoanalytic perspective, where the voice may bring to consciousness the repressed fears and desires of the unconscious. The liminal phase of ritual performance is a time of inherent possibility, where the usual social structures are inverted or subverted, but the liminal is ultimately temporary and conservative. Victor Turner suggests the concept of the ‘liminoid’ as a more transgressive alternative to the liminal, allowing for permanent and lasting social change. It may be in the liminoid realm of avant-garde performance that voices can be reimagined inside the frame of performance, as a means of exploring new forms of expression in life.