The Status and Function of Minstrels in England Between 1350 and 1400

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Champ Readies for Belmont Breeders= Cup

TUESDAY, JUNE 2, 2015 732-747-8060 $ TDN Home Page Click Here THE CHAMP READIES FOR BELMONT GLENEAGLES, FOUND TO BYPASS EPSOM GI Kentucky Derby and GI Preakness S. winner The Coolmore partners= dual Guineas winner American Pharoah (Pioneerof the Nile) registered his last Gleneagles (Ire) (Galileo {Ire}) and Group 1-winning filly serious work before Saturday=s GI Belmont S. under Found (Ire) (Galileo {Ire}) are no longer under cloudy skies Monday at consideration for Saturday=s Churchill Downs. The bay G1 Epsom Derby, and both covered five panels in will target mile races at 1:00.20 (video) with Royal Ascot. Martin Garcia in the irons Gleneagles was removed shortly after the from the Classic at renovation break. Monday=s scratching stage Churchill clocker John and will head to the G1 St. Nichols recorded 1/8-mile James=s Palace S. on the opening day of the Royal fractions in :13, :25 meeting June 16. Found, (:12), :36.60 (11.60) and who has been second in :48.60 (:12). He galloped Gleneagles winning the Irish both starts this year out six furlongs in 1:13, 2000 Guineas including the G1 Irish 1000 seven-eighths in 1:26 and Racing Post Photo Guineas May 24, will a mile in 1:39.60. contest the G1 Coronation Baffert noted how S. June 19. Found would have had to be supplemented pleased he was with the to the Derby at a cost of ,75,000. Coolmore and American Pharoah work later in the morning. trainer Aidan O=Brien are expected to be represented in Horsephotos AEverything went really the Derby by G3 Chester Vase scorer Hans Holbein well today,@ Hall of Fame (GB) (Montjeu {Ire}), owned in partnership with Teo Ah trainer Bob Baffert said outside Barn 33. -

The Trecento Lute

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title The Trecento Lute Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1kh2f9kn Author Minamino, Hiroyuki Publication Date 2019 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Trecento Lute1 Hiroyuki Minamino ABSTRACT From the initial stage of its cultivation in Italy in the late thirteenth century, the lute was regarded as a noble instrument among various types of the trecento musical instruments, favored by both the upper-class amateurs and professional court giullari, participated in the ensemble of other bas instruments such as the fiddle or gittern, accompanied the singers, and provided music for the dancers. Indeed, its delicate sound was more suitable in the inner chambers of courts and the quiet gardens of bourgeois villas than in the uproarious battle fields and the busy streets of towns. KEYWORDS Lute, Trecento, Italy, Bas instrument, Giullari any studies on the origin of the lute begin with ancient Mesopota- mian, Egyptian, Greek, or Roman musical instruments that carry a fingerboard (either long or short) over which various numbers M 2 of strings stretch. The Arabic ud, first widely introduced into Europe by the Moors during their conquest of Spain in the eighth century, has been suggest- ed to be the direct ancestor of the lute. If this is the case, not much is known about when, where, and how the European lute evolved from the ud. The presence of Arabs in the Iberian Peninsula and their cultivation of musical instruments during the middle ages suggest that a variety of instruments were made by Arab craftsmen in Spain. -

NL-Spring-2020-For-Web.Pdf

RANCHO SAN ANTONIO Boys Home, Inc. 21000 Plummer Street, Chatsworth, CA 91311 (818) 882-6400 Volume 38 No. 1 www.ranchosanantonio.org Spring 2020 God puts rainbows in the clouds so that each of us - in the dreariest and most dreaded moments - can see a possibility of hope. -Maya Angelou A REFLECTION FROM BROTHER JOHN CONNECTING WITH OUR COMMUNITY I would like to share with you a letter from a parent: outh develop a sense of identity and value “Dear All of You at Rancho, Ythrough culture and connections. To increase cultural awareness and With the simplicity of a child, and heart full of sensitivity within our gratitude and appreciation of a parent…I thank Rancho community, each one of you, for your concern and giving of Black History Month yourselves in trying to make one more life a little was celebrated in Febru- happier… ary with a fun and edu- I know they weren’t all happy days nor easy days… cational scavenger hunt some were heartbreaking days… “give up” days… that incorporated impor- so to each of you, thank you. For you to know even tant historical facts. For entertainment, one of our one life has breathed easier because you lived, this very talented staff, a professional saxophone player, is to have succeeded. and his bandmates played Jazz music for our youth Your lives may never touch my son’s again, but I during our celebratory dinner. have faith your labor has not been in vain. And to each one of you young men, I shall pray, with ACTIVITIES DEPARTMENT UPDATE each new life that comes your way… may wisdom guide your tongue as you soothe the hearts of to- ancho’s Activities Department developed a morrow’s men. -

Theories on the Origin Cj' Courtly Love

111<?ories on the ori8in cif Court!>, Love 63 share a Humber of themes and motifs, some of which may be II Theories on the origin cj' Courtly Love enumerate,l: the use of the pseudonym or senhal to conceal the identity of the lady addressed; the masculine form of address, instead of madomna; the same dramatis personae, such as the the slanderer and the confidant; the same pathological symptoms of love, namely insomnia, pallor, emaciation and HISPANO-ARABIC melancholy; a belief in the fatal consequences of this malady, Lon: was either imported into the south of France from known a<~ 'isllq or Qmor hcrcos; and the use of the Muslim Spain, or \\'<15 strongly influcnccd Il) the culture, podry and Eckl'r (1934); Nykl (1939); Mefll~ndez Pidal (1941); philosophy of the Arabs. Peres (1947); U:vi-I'roven<;:al (1948); Nelli (1963); Dutton (I 9bS); Hussein (197 I ). I)'. (a) Scholarship and ctJltU[C of the Islamic world. It was from the Arabs, in pact Some, ifnot all, the essential features of from the tenth onwards, that Christian Europe became l.ove can he discerned in Hispano-Arabic (and even better acquainted with Hellenic culture. Europe, which was still Middle Eastern) poetry: the insatiability of desire; the description emerging from barbarism, assimilated the literary, scientific and of love as exguisite anguish; the elevation of the lady into an technological achievements of a civilisation which had already of worship; the poet's submission to her capricious tyranny; and reached its maturity. Lampillas (177 ii-SI ); Andres (1782-1822); the emphasis on the need for secrecy. -

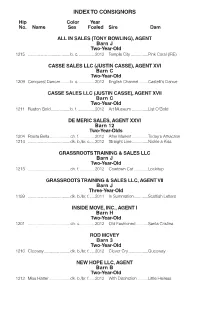

INDEX to CONSIGNORS Hip Color Year No

INDEX TO CONSIGNORS Hip Color Year No. Name Sex Foaled Sire Dam ALL IN SALES (TONY BOWLING), AGENT Barn J Two-Year-Old 1215 ................................. ......b. c. ...............2012 Temple City ................Pink Coral (IRE) CASSE SALES LLC (JUSTIN CASSE), AGENT XVI Barn C Two-Year-Old 1209 Conquest Dancer .........b. c. ...............2012 English Channel ........Castelli's Dance CASSE SALES LLC (JUSTIN CASSE), AGENT XVII Barn C Two-Year-Old 1211 Ruston Gold ..................b. f. ................2012 Art Museum ...............List O'Gold DE MERIC SALES, AGENT XXVI Barn 12 Two-Year-Olds 1204 Rosita Bella ...................ch. f. ..............2012 After Market ...............Today's Attraction 1214 ................................. ......dk. b./br. c. ....2012 Straight Line ...............Nickle a Kiss GRASSROOTS TRAINING & SALES LLC Barn J Two-Year-Old 1213 ................................. ......ch. f. ..............2012 Cowtown Cat .............Lockitup GRASSROOTS TRAINING & SALES LLC, AGENT VII Barn J Three-Year-Old 1199 ................................. ......dk. b./br. f. .....2011 In Summation .............Scottish Letters INSIDE MOVE, INC., AGENT I Barn H Two-Year-Old 1201 ................................. ......ch. c. .............2012 Old Fashioned ...........Santa Cristina ROD MCVEY Barn 3 Two-Year-Old 1216 Cleeway ........................dk. b./br. f. .....2012 Clever Cry ..................Queeway NEW HOPE LLC, AGENT Barn B Two-Year-Old 1212 Miss Hatter ....................dk. b./br. f. .....2012 With Distinction -

IMPINGE (NZ) 49 Bay Mare (Branded Nr Sh

Barn J Stables 29-36, 45-52, 61-64 On Account of EDINGLASSIE STUD, Muswellbrook (As Agent) Lot 600 IMPINGE (NZ) 49 Bay mare (Branded nr sh. off sh.) Foaled 2001 1 Nijinsky ...........................by Northern Dancer ... Caerleon ......................... SIRE Foreseer .................... by Round Table ........... GENEROUS (IRE) ..... Master Derby ............. by Dust Commander .... Doff the Derby ............... Margarethen .............. by Tulyar .................... Storm Bird .................. by Northern Dancer ... DAM Bluebird (USA) ................ Ivory Dawn ................ by Sir Ivor ................... IMCO RESOURCE (IRE) Saratoga Six ............... by Alydar .................... 1996 Sasimoto ....................... Mobcap ...................... by Tom Rolfe .............. GENEROUS (IRE) (1988). 5 wins, Ascot King George VI & Queen Elizabeth Diamond S., Gr.1. Sire of 995 rnrs, 652 wnrs, 45 SW, inc. SW Catella, etc. Sire of the dams of SW Gingernuts, Lion Tamer, Golan, Survived, Nahrain, Mourinho, We Can Say it Now, Proportional, Al Shemali, Mackintosh, Dandino, No Evidence Needed, Armure, Tartan Bearer, Essential Edge, Tungsten Strike, High Accolade, Black Moon, Vote Often, etc. 1st Dam IMCO RESOURCE (IRE), by Bluebird (USA). 2 wins at 2 at 1600m, Rome Premio Disco Rosso. Dam of 8 named foals, all raced, 5 winners, inc:- THAT'S NOT IT (g by Foreplay). 2 wins at 1100m, 1200m, $209,540, MVRC Red Anchor S., Gr 3, 2d VRC Moomba P., L. Impinge (f by Generous (Ire)). 3 wins. See below. 2nd Dam SASIMOTO, by Saratoga Six. 5 wins–3 at 2–1000m to 1400m, Milan Criterium Nazionale, L, Rome Premio Aniene, L, 3d Rome Criterium Femminile, L. Half- sister to NOTEBOOK. Dam of 11 foals, 8 to race, 7 winners, inc:- Blue Shift. 8 wins 1000m to 1408m, Rome Premio Nipissing. -

The Minstrel Legacy: African American English and the Historical Construction of “Black” Identities in Entertainment

Africana Studies Faculty Publications Africana Studies 12-2015 The insM trel Legacy: African American English and the Historical Construction of "Black" Identities in Entertainment Jennifer Bloomquist Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/afsfac Part of the African American Studies Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Linguistics Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Bloomquist, Jennifer. "The inM strel Legacy: African American English and the Historical Construction of "Black" Identities in Entertainment." Journal of African American Studies 19, no. 4 (December 2015). 410-425. This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/afsfac/22 This open access article is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The insM trel Legacy: African American English and the Historical Construction of "Black" Identities in Entertainment Abstract Linguists have long been aware that the language scripted for "ethnic" roles in the media has been manipulated for a variety of purposes ranging from the construction of character "authenticity" to flagrant ridicule. This paper provides a brief overview of the history of African American roles in the entertainment industry from minstrel shows to present-day films. I am particularly interested in looking at the practice of distorting African American English as an historical artifact which is commonplace in the entertainment industry today. -

King George VI & Queen Elizabeth Stakes (Sponsored by QIPCO)

King George VI & Queen Elizabeth Stakes (Sponsored by QIPCO) Ascot Racecourse Background Information for the 65th Running Saturday, July 25, 2015 Winners of the Investec Derby going on to the King George VI & Queen Elizabeth Stakes (Sponsored by QIPCO) Unbeaten Golden Horn, whose victories this year include the Investec Derby and the Coral-Eclipse, will try to become the 14th Derby winner to go on to success in Ascot’s midsummer highlight, the Group One King George VI & Queen Elizabeth Stakes (Sponsored by QIPCO), in the same year and the first since Galileo in 2001. Britain's premier all-aged 12-furlong contest, worth a boosted £1.215 million this year, takes place at 3.50pm on Saturday, July 25. Golden Horn extended his perfect record to five races on July 4 in the 10-furlong Group One Coral- Eclipse at Sandown Park, beating older opponents for the first time in great style. The three-year-old Cape Cross colt, owned by breeder Anthony Oppenheimer and trained by John Gosden in Newmarket, captured Britain's premier Classic, the Investec Derby, over 12 furlongs at Epsom Downs impressively on June 6 after being supplemented following a runaway Betfred Dante Stakes success at York in May. If successful at Ascot on July 25, Golden Horn would also become the fourth horse capture the Derby, Eclipse and King George in the same year. ËËË Three horses have completed the Derby/Eclipse/King George treble in the same year - Nashwan (1989), Mill Reef (1971) and Tulyar (1952). ËËË The 2001 King George VI & Queen Elizabeth Stakes saw Galileo become the first Derby winner at Epsom Downs to win the Ascot contest since Lammtarra in 1995. -

P Edigree Insights

Andrew Caulfield, June 29, 2004–Grey Swallow (Ire) P EDIGREE INSIGHTS The presence among the broodmare sires of several other notable mile-and-a-half performers meant that BY ANDREW CAULFIELD Daylami did well to come up with eight winners from his first 26 runners in Britain and Ireland, with further BUDWEISER IRISH DERBY-G1, i1,199,100, The winners in France and Norway. His daughter Bay Tree Curragh, 6-27, 3yo, c/f, 1 1/2mT, 2:28.70, gd/fm. had become his first stakes winner and his second, Grey 1--sGREY SWALLOW (IRE), 126, c, 3, by Daylami (Ire) Swallow, was rated the second-best two-year-old colt 1st Dam: Style Of Life, by The Minstrel of 2003. Daylami also earned black type through the 2nd Dam: Bubinka, by Nashua speedy filly Birthday Suit and the Group 1-placed Day or 3rd Dam: Stolen Date, by Sadair Night. I had also been impressed by another Daylami (150,000gns yrl ‘02 TATHOU). O-Rochelle Quinn; colt, Thajja, but injury prevented this youngster from B-Mrs C L Weld; T-D Weld; J-P Smullen; i736,600. adding to his debut win. Lifetime Record: 6-4-0-1, i882,011. *1/2 to Central The winners have continued to flow from Daylami's Lobby (Ire) (Kenmare {Fr}), GSP-Fr, $232,027. first crop, with Hidden Hope becoming his third stakes Click for the free brisnet.com catalogue-style pedigree winner in the Cheshire Oaks, while Day or Night failed or the racingpost.co.uk chart. by only a short neck to take the G2 Prix Greffulhe. -

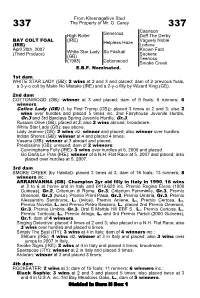

From Kileenagallive Stud the Property of Mr. G. Carey

From Kileenagallive Stud 337 The Property of Mr. G. Carey 337 Caerleon High Roller Generous Doff The Derby (IRE) Vaguely Noble BAY COLT FOAL Helpless Haze (IRE) Lodeve April 20th, 2007 Known Fact (Third Produce) White Star Lady So Factual Sookera (GB) Teenoso (1998) Cottonwood Smoke Creek E.B.F. Nominated. 1st dam WHITE STAR LADY (GB): 2 wins at 2 and 3 and placed; dam of 2 previous foals, a 3-y-o colt by Make No Mistake (IRE) and a 2-y-o filly by Wizard King (GB). 2nd dam COTTONWOOD (GB): winner at 3 and placed; dam of 9 foals; 6 runners; 6 winners: Calico Lady (GB) (f. by First Trump (GB)): placed 3 times at 2 and 3; also 2 wins over hurdles and placed 5 times inc. 2nd Fairyhouse Juvenile Hurdle, Gr.3 and 3rd Barclays Spring Juvenile Hurdle, Gr.3. Russian Olive (GB): placed at 2; also 2 wins abroad; broodmare. White Star Lady (GB): see above. Lady Jeannie (GB): 2 wins viz. winner and placed; also winner over hurdles. Indian Shores (GB): winner at 4 and placed 4 times. Vasana (GB): winner at 3 abroad and placed. Prestissimo (GB): unraced; dam of 2 winners: Cunninghams Folly (IRE): 3 wins over hurdles at 5, 2006 and placed. Go Dana Le Pras (IRE): winner of a N.H. Flat Race at 5, 2007 and placed; also placed over hurdles at 5, 2007. 3rd dam SMOKE CREEK (by Habitat): placed 3 times at 3; dam of 16 foals; 13 runners; 8 winners inc.: ARRANVANNA (GB): Champion 2yr old filly in Italy in 1990, 16 wins at 2 to 6 at home and in Italy and £419,628 inc. -

Dubai Duty Free Shergar Cup

DUBAI DUTY FREE SHERGAR CUP Ascot, Saturday, August 11, 2012 MEDIA GUIDE INDEX 3 THE DUBAI DUTY FREE SHERGAR CUP 4 ORDER OF RUNNING & ADMISSION DETAILS 5 TIMETABLE OF EVENTS, FAMILY ENTERTAINMENT 6 POST-RACING CONCERT – “HERE AND NOW” THE VERY BEST OF THE 1980’s 7 THE PRIZES 8 “BEST DAY’S RACING FOR OWNERS”, DETAILS OF RESERVES, LADBROKES – OFFICAL BOOKMAKER 9 DUBAI DUTY FREE SHERGAR CUP RULES DUBAI DUTY FREE SHERGAR CUP 'DRAW' PROCEDURE & ALLOCATION OF MOUNTS 10 – 13 PROFILES OF PARTICIPATING JOCKEYS 14 PAST WINNERS OF THE “SILVER SADDLE” FOR LEADING JOCKEY AT THE DUBAI DUTY FREE SHERGAR CUP 15 REMEMBERING SHERGAR 16 ABOUT DUBAI DUTY FREE – SPONSORSHIP SUCCESS AS SALES SOAR 17 – 36 PAST RESULTS AT THE DUBAI DUTY FREE SHERGAR CUP 37 KEY ASCOT CONTACTS, ACCREDITATION & MEDIA SERVICES 2 THE DUBAI DUTY FREE SHERGAR CUP • The Dubai Duty Free Shergar Cup is Britain's premier jockeys' competition, a unique event where top jockeys in four teams - Great Britain and Ireland, Europe, the Rest of the World and for the first time this year The Girls - battle against each other in a thrilling six- race showdown. • The six races are limited to 10 runners with either two or three horses racing for each team (this will balance itself out over the course of the afternoon), and points are awarded on a 15, 10, 7, 5, 3 basis to the first five horses home (non runners score 4 points). Subject to full fields, each jockey has five rides and the team with the highest total after the sixth race lifts the Dubai Duty Free Shergar Cup. -

Obscene Anglo-Norman in a Central French Mouth; Or, How Renart the Fox Tricks Isengrin the Wolf, and Why It Is Important

Obscene Anglo-Norman in a Central French Mouth; or, How Renart the Fox Tricks Isengrin the Wolf, and Why It Is Important William Calin In Branch lb of the late twelfth-century Roman de Renart, Renart the Fox, believed to be dead, falls into a vat of dye colouring. This enables him to return home, in disguise, claiming to be an English jongleur. Upon encountering his old enemy, Isengrin the Wolf, Renart plays his role, uttering a broken French which, presumably, the medieval audience recognised as a caricatural version of Anglo-Norman, the French spoken in England, and/or as the imperfect speech of a foreigner only superficially versed in the language. The encounter between Renart and Isengrin runs on for a good two hundred lines. I shall discuss the first few lines, one page taken from the Combarieu-Subrenat edition.1 Here follows the original text, the editors' translation into French, and my translation into English. Old French Text Lors se porpense en son corage Que il changera son langaje. 2340 Ysengrin garde cele part Et voit venir vers lui Renart. Drece la poe, si se seigne Ançois que il a lui parveigne, Plus de cent fois, si con je cuit; Florilegium 18. (2001) 8 Renart Tricks Isengrin Tel poor a, por poi ne fuit. Qant ce out fet, puis si s'areste Et dit que mes ne vit tel beste, D'estranges terres est venue. Ez vos Renart qui le salue: 2350 — "Godehelpe" fait il, "bel sire! Non saver point ton reson dire." — "Et Dex saut vos, bau dous amis! Dont estes vos? de quel païs? Vos n'estes mie nés de France Ne de la nostre connoissance." — "Nai, mi seignor, mais de Bretaing.