2 Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charlie Sykes

CHARLIE SYKES EDITOR-AT-LARGE, THE BULWARK Quick Summary Life in Brief Former conservative radio host and Wisconsin Hometown: Seattle, WA Republican kingmaker who gained national prominence as a leading voice in the Never Trump Current Residence: Mequon, WI movement and created the Bulwark website as a messaging arm for like-minded conservatives Education: • BA, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, • Love for journalism and politics heavily influenced 1975 by his father • Self-described “recovering liberal” who criticizes Family: both political parties for inflexibility and for • Married to Janet Riordan alienating those who reject status quo • Three children, two grandchildren • As conservative radio host, cultivated significant influence in Wisconsin GOP politics – quickly Work History: becoming a go-to stop for Republican candidates; • Editor-at-Large, The Bulwark, 2019- drew significant attention to issues like school Present choice • Host, The Daily Standard, 2018 • Became national figure after refusing to support • Contributing editor, The Weekly Donald Trump Standard • Co-founded the Bulwark with Bill Kristol, which • Contributor, NBC/MSNBC, 2016-present has become a leading mouthpiece of the Never • Host, Indivisible WNYC, 2017 Trump conservative movement • Editor-in-Chief, Right Wisconsin • Considers himself a “political orphan” in the era of • Radio show host, WTMJ, 1999-2016 Trump after exile from conservative movement • Radio host, WISN, 1989-93 whose political identity has changed many times • PR for Dave Schulz, Milwaukee -

Radiowaves Will Be Featuring Stories About WPR and WPT's History of Innovation and Impact on Public Broadcasting Nationally

ON AIR & ONLINE FEBRUARY 2017 Final Forte WPR at 100 Meet Alex Hall Centennial Events Internships & Fellowships Featured Photo Earlier this month, WPR's To the Best of Our Knowledge explored the relationship between love WPR Next" Initiative Explores New Program Ideas and evolution at a sold- out live show in Madison, We often get asked, "Where does WPR come up with ideas for its sponsored by the Center programs?" First and foremost, we're inspired by you, our listeners for Humans in Nature. and neighbors around the state. During our 100th year, we're looking Excerpts from the show, to create the public radio programs of the future with a new initiative which included storyteller called WPR Next. Dasha Kelly Hamilton (pictured), will be We're going to try out a few new show ideas focused on science, broadcast nationally on pop culture, life in Wisconsin, and more. You can help our producers the show later this month. develop these ideas by telling us what interests you about these topics. Sound Bites Do you love science? What interests you most ---- do you wonder about new research in genetics, life on other planets, or ice cover on Winter Pledge Drive the Great Lakes? What about pop culture? What makes a great Begins February 21 book, movie or piece of music, and who would you like to hear WPR's winter interviewed? How about life in Wisconsin? What do you want to membership drive is know about our state's culture and history? What other topics would February 21 through 25. -

The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy

Mount Rushmore: The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy Brian Asher Rosenwald Wynnewood, PA Master of Arts, University of Virginia, 2009 Bachelor of Arts, University of Pennsylvania, 2006 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Virginia August, 2015 !1 © Copyright 2015 by Brian Asher Rosenwald All Rights Reserved August 2015 !2 Acknowledgements I am deeply indebted to the many people without whom this project would not have been possible. First, a huge thank you to the more than two hundred and twenty five people from the radio and political worlds who graciously took time from their busy schedules to answer my questions. Some of them put up with repeated follow ups and nagging emails as I tried to develop an understanding of the business and its political implications. They allowed me to keep most things on the record, and provided me with an understanding that simply would not have been possible without their participation. When I began this project, I never imagined that I would interview anywhere near this many people, but now, almost five years later, I cannot imagine the project without the information gleaned from these invaluable interviews. I have been fortunate enough to receive fellowships from the Fox Leadership Program at the University of Pennsylvania and the Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia, which made it far easier to complete this dissertation. I am grateful to be a part of the Fox family, both because of the great work that the program does, but also because of the terrific people who work at Fox. -

Download File

Tow Center for Digital Journalism CONSERVATIVE A Tow/Knight Report NEWSWORK A Report on the Values and Practices of Online Journalists on the Right Anthony Nadler, A.J. Bauer, and Magda Konieczna Funded by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 Introduction 7 Boundaries and Tensions Within the Online Conservative News Field 15 Training, Standards, and Practices 41 Columbia Journalism School Conservative Newswork 3 Executive Summary Through much of the 20th century, the U.S. news diet was dominated by journalism outlets that professed to operate according to principles of objectivity and nonpartisan balance. Today, news outlets that openly proclaim a political perspective — conservative, progressive, centrist, or otherwise — are more central to American life than at any time since the first journalism schools opened their doors. Conservative audiences, in particular, express far less trust in mainstream news media than do their liberal counterparts. These divides have contributed to concerns of a “post-truth” age and fanned fears that members of opposing parties no longer agree on basic facts, let alone how to report and interpret the news of the day in a credible fashion. Renewed popularity and commercial viability of openly partisan media in the United States can be traced back to the rise of conservative talk radio in the late 1980s, but the expansion of partisan news outlets has accelerated most rapidly online. This expansion has coincided with debates within many digital newsrooms. Should the ideals journalists adopted in the 20th century be preserved in a digital news landscape? Or must today’s news workers forge new relationships with their publics and find alternatives to traditional notions of journalistic objectivity, fairness, and balance? Despite the centrality of these questions to digital newsrooms, little research on “innovation in journalism” or the “future of news” has explicitly addressed how digital journalists and editors in partisan news organizations are rethinking norms. -

Discourse in the Segregated City: Racial Violence, Capital, and Milwaukee’S Media

Global Media Journal ISSN: 1550-7521 Volume 13 Issue 25 Discourse in the Segregated City: Racial Violence, Capital, and Milwaukee’s Media L. Dugan Nichols School of Communication, Simon Fraser University, 8888 University Dr. Burnaby, BC, Canada V5A 1S6, E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This paper examines the news reportage surrounding two race-related incidents that occurred in 2011 in Milwaukee, WI, one of America’s most segregated cities. The altercations involved Black youths violently encountering white attendees of a park in one case, and white attendees of the Wisconsin State Fair in the other. Milwaukee Journal Sentinel stories failed to consider longstanding social and economic injustices that might give rise to such behavior, adopting instead a relatively colorblind position. This strategy fosters the illusion that the conditions between races are equal, despite the unequal, discriminatory effect capital and the state have had on African Americans. While online Journal Sentinel reportage contained a subdued racism, many online reader comments appearing below articles were openly white supremacist. Editorials, in accordance with the coverage, called for more responsible parents instead of a more thoughtful capitalism, i.e., one that would not export manufacturing jobs or deliberately phase out the need for Black labor. Drawing on scholars such as Stuart Hall et al., I explain from a Marxian standpoint why Milwaukee’s coverage and reader comments take the shape they do. I further argue that these circumscribed case studies can help us understand the ideology at work behind more prominent (and tragic) racial incidents, such as the 2014 summer protests in Ferguson, MO. -

Wisconsin Judicial Elections Updated 02/23/04

Wisconsin Judicial Elections Updated 02/23/04 1. Two candidates for the Wisconsin Supreme court, Diane Sykes and Louis Butler, pledged to run positive campaigns. Based on her reading of the judicial code of ethics, Sykes has declared that she will not comment on pending cases or legal issues that might come before the court in the future. Sykes stated that recent races for the state high court have become similar to legislative races, with candidates taking positions on legal issues. She added, “I will not discuss cases or legal issues, period.” Doing so, she said, “risks compromising the integrity, the independence and the impartiality of the judiciary.” Butler agreed with Sykes, but said a candidate’s record, qualifications, even personal opinions are all fair game. Richard P. Jones, Sykes, Butler Vow Positive Campaigns for High Court, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, January 4, 2000. 2. Columnist argues that Wisconsin Supreme Court candidate Louis Butler “is far more qualified to sit on the state’s high court bench than the appointed justice he is challenging, conservative judicial activist Diane Sykes.” The piece argues, however, that Butler should refrain from criticizing Sykes’ ex-husband, Milwaukee radio talk show host Charlie Sykes. Butler recently suggested that Diane Sykes should publicly repudiate her ex-husband’s on-air comments about the judicial race. The columnist states, “It’s silly to suggest that Diane Sykes is responsible for what her ex-husband says. And it is equally silly to suggest that Charlie Sykes is pushing Diane’s candidacy any more aggressively than he has those of past conservative candidates for the court.” John Nichols, Charlie Sykes Upfront About Right-Wing Bent, Wis. -

What Young Conservatives Want

2013 ST What Young WI AUGU Conservatives Want WISCONSIN INTEREST BY GEORGE LIGHTBOURN MPS’ Uninspiring Leader BY MIKE NICHOLS Fear, Loathing and Obamacare BY MICHAEL FLAHERTY First Lady Tonette Walker: Survivor BY SUNNY SCHUBERT Editor > CHARLES J. SYKES The singular leadership of George Lightbourn WI WISCONSIN INTEREST The term “public servant” has been used George retired from WPRI at the too generically to retain much of its original end of June but continues to share that significance. But it is impossible to describe counsel. Our cover story this month Publisher: Wisconsin Policy Research George Lightbourn without invoking the is an account of a provocative dinner Institute, Inc. concept in its fullest original sense. During conversation that George and I had with Editor: both his years in state government and his a group of young conservatives, who Charles J. Sykes second career as president of the Wisconsin candidly expressed their uneasiness with Managing Editor: Policy Research Institute, George has aspects of conservatism and the failure Marc Eisen combined service and leadership. of the Republican Party to connect with Art Direction: Stephan & Brady, Inc. In particular, he has been instrumental younger, more moderate voters. The edited Contributors: in the resurrection of this magazine, transcript fairly captures the back and forth Richard Esenberg transforming it from a staid (and usually and, while not all of our readers will share Michael Flaherty unread) journal into what you have in your their views, those views are a valuable Warren Kozak George Lightbourn hand now. George brought to his duties starting point for further debate. Mike Nichols not only a vast reservoir of knowledge, George has been succeeded as WPRI Christian Schneider Sunny Schubert but also a finely honed, wry humor and president by senior fellow Mike Nichols. -

Defendant's Memo on Examples of Prejudicial Pretrial Publicity

( ( STATE OF WISCONSIN CIRCUIT COURT MANITOWOC COUI{TY Srern or WrscoNSrN, &{Afltrcw0c colrsff FEtffiffig?e?e oF&18e0$8$r Plaintiff, iul 14 200$ a. Case No. 2005-CF-381 trt*ffiffi SF fifftSEJtT UffWRT SrnvEN A. AvEnv, Defendant. DEFENDANT'S MEMORANDUM ON EXAMPLES OF PREIUDICIAL PRETRIAL PUBLICITY I. INTRODUCTION Steven Avery has assembled a sample of the massive pretrial publicity in this case/ and submitted that to the Court (without objection from the state) in the form of 24 DVD's of television coverage of the investigation into Teresa Halbach's disappearance and this prosecution, and two banker's boxes of photocopies of newspaper articles, teleprompter scripts, radio broadcasts, and comment on the case from websites. This case has received saturation coverage. In part because of his change of counsel, from the Wisconsin Public Defender's office to retained counsel, and in partbecause the task would have been impossible, Mr. Avery mad.e no effort R) (,) to collect all media coverage of this case. The earlier Affidavit of Dean A. Strang outlines in overview the contents of the sample materials he did gather. Because even that mass of information remains daunting (the television coverage alone apparently runs to more than 20 hours of back-to-back clips relating to this case), Avery now offers a sample of his samples. The discussion that follows is illustrative, not exhaustive, and Mr. Avery stands in the end on all of the evidence of pretrial publicity in the record. II. EXAMPLES A. Recurring Themes. The defense has submitted 24DVD's of nothing but Avery clips, with at least one of the DVD's more than 2 hours long. -

Weekly Update September 14, 2012

WWEEEEKKLLYY UUPPDDAATTEE WSTA would like to recognize our 2012 GOLD and SILVER Annual Partners: GOLD – Finley Engineering Company, Inc. SILVER - Interstate Telcom Consulting, Inc., Kiesling Associates LLP, and National Inform ation Solutions Cooperative, Inc. (NISC) Thank you National Information Solutions Cooperative and HickoryTech for your sponsorship of WSTA electronic publications! Associate members, click here to join them! Weekly Update September 14, 2012 Legislative and Political Judge throws out Walker's union bargaining law Gov. Scott Walker's law repealing most collective bargaining for local and school employees was struck down by a Dane County judge Friday, yet another dramatic twist in a year and a half saga that likely sets up another showdown in the Supreme Court. The law remains largely in force for state workers, but for city, county and school workers the decision by Dane County Judge Juan Colas returns the law to its status before Walker signed the legislation in March 2011. Colas ruled that the law violated workers' constitutional rights to free speech, free association and equal representation under the law by capping union workers' raises but not those of their nonunion counterparts. The judge also ruled that the law violated the "home rule" clause of the state constitution by setting the contribution for City of Milwaukee employees to the city pension system rather than leaving it to the city and workers. The decision could still be overturned on appeal - the Supreme Court has already restored the law once in June 2011 after it was blocked by a different Dane County judge in a different case earlier that year. -

Virtual Conference Program

VIRTUAL CONFERENCE PROGRAM National Council for the Social Studies www.socialstudies.org 2020 @NCSSNetwork December 4–6 #NCSS2020 CONNECT WITH US District Outreach Contacts Email Addresses Board of Governors District of Columbia Laura Shipley [email protected] District of Columbia Jean Durr [email protected] District 2 New York Graham Long [email protected] District 3 Philadelphia Todd Zartman [email protected] District 4 Cleveland Khaz Finley [email protected] Cincinnati Branch Alexandria Halmbacher [email protected] Pittsburgh Branch Cariss Turner Smith [email protected] District 5 Richmond David Bass [email protected] Baltimore Branch Kevin Woodcox [email protected] Charlotte Branch Yolanda Ferguson [email protected] District 6 Atlanta Princeton Williams [email protected] Birmingham Branch Julie Kornegay [email protected] Jacksonville Branch Lesley Mace [email protected] Miami Branch Gloria Guzman [email protected] Nashville Branch Jackie Morgan [email protected] New Orleans Branch Claire Loup [email protected] District 7 Chicago/Detroit Dustchin Rock [email protected] District 8 St. Louis Mary Suiter [email protected] Little Rock Branch Kris Bertelsen [email protected] Louisville Branch David Perkis [email protected] Memphis Branch Jeannette Bennett [email protected] District 10 Kansas City Gigi Wolf [email protected] Denver Branch Erin Davis [email protected] -

Win, Lose Or Draw?

WI MARCH 2012 WISCONSIN INTEREST Behind the disorder in the court BY MICHAEL GABLEMAN Anatomy of a dysfunctional school district BY MIKE NICHOLS Win, Lose A feisty champion for business or Draw? BY SUNNY SCHUBERT Wisconsin’s alternative futures BY JEFF MAYERS The two Wisconsins at war BY CHARLES J. SYKES Editor > CHARLES J. SYKES WI The age of uncertainty WISCONSIN INTEREST What if? Doe investigation, and even the timing Let’s be honest. Nobody knows what lies of the elections themselves. As Mayers ahead, except that 2012 will be the biggest, notes, “The most predictable thing is the Publisher: Wisconsin Policy Research most expensive and consequential political unpredictability of the what-if scenarios Institute, Inc. year in Wisconsin history. and the political times we’re in.” Editor: Our cover story is an encore of sorts. Meanwhile, the narrowly balanced Charles J. Sykes Back in 2000, we asked WisPolitics. Wisconsin State Supreme Court remains Managing Editor: com founder Jeff Mayers to examine at the center of controversy. In our last Marc Eisen the alternative scenarios of that year’s issue, we featured an interview with Art Direction: elections, and it became one of the Justice David Prosser. In this issue, Stephan & Brady, Inc. most talked about stories of the year. embattled Justice Michael Gableman Contributors: In retrospect, the stakes of that election Richard Esenberg weighs in with a critique of the divisions Michael Gableman appear almost quaint compared with the on the court, adapted from remarks he Mike Nichols potential for political Armageddon we delivered at the annual dinner of the Michael J. -

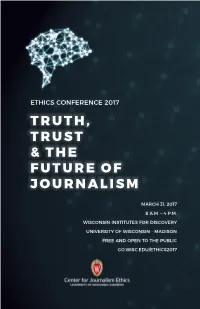

Truth, Trust & the Future of Journalism

ETHICS CONFERENCE 2017 TRUTH, TRUST & THE FUTURE OF JOURNALISM MARCH 31, 2017 8 A.M. – 4 P.M. WISCONSIN INSTITUTES FOR DISCOVERY UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN - MADISON FREE AND OPEN TO THE PUBLIC GO.WISC.EDU/ETHICS2017 THE CENTER FOR JOURNALISM ETHICS A year ago, I would have found last week’s TIME magazine cover ADVISORY 9 - 10 AM KEYNOTE: Margaret Sullivan of The Washington Post shocking. In bold red letters on a black background, the cover asks: “Is Truth Dead?” BOARD Katy Culver, interviewer While I may have found this provocative question unreal last spring, today I find myself all too often asking whether we have TOM BIER 10-11 AM PANEL 1: THE RESPONSIBILITY & CHALLENGE OF indeed entered a “post-truth” era. I shudder a bit even typing KATHY BISSEN TRUTH: FACT, FICTION AND NEWS that phrase, but we are in a historic moment many find uniquely JAMES BURGESS unsettling. Jason Shepard SCOTT COHN Today is going to be one of tough questions. What does RICK FETHERSTON Lucas Graves journalism do when it is under attack? Can a democracy survive PETER D. FOX Raney Aronson-Rath without a free, strong and responsible press? What have we ELLEN FOLEY ourselves done to weaken news media practices and hinder the Ken Vogel JILL GEISLER public’s trust in us? What are the paths forward? MARTIN KAISER Jason Stein We’re going to hear about some encouraging things, including JACK MITCHELL the rise of the fact-checking movement and the strength of JOHN SMALLEY 11:15 AM investigative work. We’re also going to hear solid critiques, PANEL 2: BLIND BELIEFS? CONSPIRACIES, HOAXES CAROL TOUSSAINT including allowing news cycles to be dominated and credibility AND DISINFORMATION OWEN ULLMANN -12:15 PM to be undermined.