Understanding Hillforts: Have We Progressed? by Barry Cunliffe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roman Conquest, Occupation and Settlement of Wales AD 47–410

no nonsense Roman Conquest, Occupation and Settlement of Wales AD 47–410 – interpretation ltd interpretation Contract number 1446 May 2011 no nonsense–interpretation ltd 27 Lyth Hill Road Bayston Hill Shrewsbury SY3 0EW www.nononsense-interpretation.co.uk Cadw would like to thank Richard Brewer, Research Keeper of Roman Archaeology, Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales, for his insight, help and support throughout the writing of this plan. Roman Conquest, Occupation and Settlement of Wales AD 47-410 Cadw 2011 no nonsense-interpretation ltd 2 Contents 1. Roman conquest, occupation and settlement of Wales AD 47410 .............................................. 5 1.1 Relationship to other plans under the HTP............................................................................. 5 1.2 Linking our Roman assets ....................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Sites not in Wales .................................................................................................................... 9 1.4 Criteria for the selection of sites in this plan .......................................................................... 9 2. Why read this plan? ...................................................................................................................... 10 2.1 Aim what we want to achieve ........................................................................................... 10 2.2 Objectives............................................................................................................................. -

Ompras Dorset

www.visit-dorset.com #visitdorset Bienvenido Nuestro pasado más antiguo vendrá a tu encuentro en Dorset, desde los acantilados jurásicos plagados de fósiles en los alrededores de Presentación de Dorset la romántica Lyme Regis hasta el imponente arco en piedra caliza Más información sobre cómo llegar hasta Dorset: ver p. 23. conocido como la Puerta de Durdle en la espectacular costa que ha sido declarada Patrimonio de la Humanidad. En el interior, Dorset Más lugares para visitar en Dorset: cuenta con acogedoras poblaciones conocidas tradicionalmente www.visit-dorset.com por sus mercados, ondulantes colinas de creta blanca en la parte Síguenos en: norte y el misterioso Gigante de Cerne Abbas. Vayas donde vayas tendrás consciencia del profundo sentido histórico de este condado, VisitDorset enmarcado por una fascinante belleza escénica. Descubre la colorida historia del Castillo de Highcliffe en Christchurch, visita el Puerto de #visitdorset Portland, donde tuvieron lugar las competiciones de vela de los Juegos Olímpicos y Paralímpicos de Londres en 2012, recorre los caminos OfficialVisitDorset de los acantilados en la Isla de Purbeck para disfrutar de magníficas VisitDorsetOfficial vistas de Old Harry Rocks o relájate en las interminables playas de la Bahía de Studland. Sal de picnic con la familia para pasar un día inolvidable en las resguardadas playas de Weymouth o Swanage, deja que el viento acaricie tu rostro en la rocosa playa de Chesil, o trepa por la empedrada Gold Hill en Shaftesbury para ver las privilegiadas vistas panorámicas del valle de Blackmore. Dorset te depara todo esto y más, incluyendo las brillantes luces de las cercanas Bournemouth y Poole y las rutas de senderismo del Parque Nacional de New Forest. -

Archaeological Investigations in St John's, Worcester

Worcestershire Archaeology Research Report No.4 Archaeological Investigations in ST JOHN’S WORCESTER Jo Wainwright Worcestershire Archaeology Research Report no 4 Archaeological Investigations in St John’s, Worcester (WCM 101591) Jo Wainwright With contributions by Ian Baxter, Hilary Cool, Nick Daffern, C Jane Evans, Kay Hartley, Cathy King, Elizabeth Pearson, Roger Tomlin, Gaynor Western and Dennis Williams Illustrations by Carolyn Hunt and Laura Templeton 2014 Worcestershire Archaeology Research Report no 4 Archaeological Investigations in St John’s, Worcester Published by Worcestershire Archaeology Archive & Archaeology Service, The Hive, Sawmill Walk, The Butts, Worcester. WR1 3PD ISBN 978-0-9929400-4-1 © Worcestershire County Council 2014 Worcestershire ,County Council County Hall, Spetchley Road, Worcester. WR5 2NP This document is presented in a format for digital use. High-resolution versions may be obtained from the publisher. [email protected] Front cover illustration: view across the north-west of the site, towards Worcester Cathedral to previous view Contents Summary ..........................................................1 Background ..........................................................2 Circumstances of the project ..........................................2 Aims and objectives .................................................3 The character of the prehistoric enclosure ................................3 The hinterland of Roman Worcester and identification of survival of Roman landscape -

Early Medieval Dykes (400 to 850 Ad)

EARLY MEDIEVAL DYKES (400 TO 850 AD) A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2015 Erik Grigg School of Arts, Languages and Cultures Contents Table of figures ................................................................................................ 3 Abstract ........................................................................................................... 6 Declaration ...................................................................................................... 7 Acknowledgments ........................................................................................... 9 1 INTRODUCTION AND METHODOLOGY ................................................. 10 1.1 The history of dyke studies ................................................................. 13 1.2 The methodology used to analyse dykes ............................................ 26 2 THE CHARACTERISTICS OF THE DYKES ............................................. 36 2.1 Identification and classification ........................................................... 37 2.2 Tables ................................................................................................. 39 2.3 Probable early-medieval dykes ........................................................... 42 2.4 Possible early-medieval dykes ........................................................... 48 2.5 Probable rebuilt prehistoric or Roman dykes ...................................... 51 2.6 Probable reused prehistoric -

Ancient Defensive Earthworks Fortified

CONGRESS OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETIES IN UNION WITH THE SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES OF LONDON. SCHEME FOR RECORDING ANCIENT DEFENSIVE EARTHWORKS AND FORTIFIED ENCLOSURES. 1903. COMMITTEE FOR RECORDING ANCIENT DEFENSIVE EARTHWORKS AND FORTIFIED ENCLOSURES. LORD BALCARRES, M.P., F.S.A., Chairman. W. J. ANDREW, F.S.A. F. HAVERFIELD, F.S.A., MA. F. W. ATTREE (Lt.-Col. R.E.), W. H. ST. J. HOPE, M.A. F.S.A. BOYD DAWICINS (Prof.), F.R.S., J. HORACE ROUND, M.A. F.S.A. SIR JOHN EVANS, K.C.B., F.R.S., O. E. RUCK (Lt.-Col. RE.), V.P.S.A. F.S.A.Sc. A. R. GODDARD, B.A. W. M. TAPP, LL.D. BERTRAM C. A. WINDLE (Prof.), F.R.S., F.S.A. I. CHALKLEY GOULD, Hon. Sec. {Royal Societies' Club, St. James's Street, London.) EXTRACT from the Report of the Provisional Committee to the Congress of Archaeological Societies :— "There is need, not only for schedules such as this Committee is appointed to secure, but also for active antiquaries in all parts of the country to keep keen watch over ancient fortifications of earth and stone, and to endeavour to prevent their destruction by the hand of man in this utilitarian age." SCHEME FOR RECORDING ANCIENT DEFENSIVE EARTHWORKS AND FORTIFIED ENCLOSURES. » T the Congress of the Archaeological Societies, held on A July ioth, 1901, a Committee was appointed to prepare a scheme for a systematic record of ANCIENT DEFENSIVE EARTHWORKS AND FORTIFIED ENCLOSURES. It was suggested that the secretaries of the various archaeological societies, and other gentlemen likely to be interested in the subject, should be pressed to prepare schedules of the works in their respective districts, in the hope that lists may eventually be published. -

The Iron Age Tom Moore

The Iron Age Tom Moore INTRODUCfiON In the twenty years since Alan Saville's (1984) review of the Iron Age in Gloucestershire much has happened in Iron-Age archaeology, both in the region and beyond.1 Saville's paper marked an important point in Iron-Age studies in Gloucestershire and was matched by an increasing level of research both regionally and nationally. The mid 1980s saw a number of discussions of the Iron Age in the county, including those by Cunliffe (1984b) and Darvill (1987), whilst reviews were conducted for Avon (Burrow 1987) and Somerset (Cunliffe 1982). At the same time significant advances and developments in British Iron-Age studies as a whole had a direct impact on how the period was viewed in the region. Richard Hingley's (1984) examination of the Iron-Age landscapes of Oxfordshire suggested a division between more integrated unenclosed communities in the Upper Thames Valley and isolated enclosure communities on the Cotswold uplands, arguing for very different social systems in the two areas. In contrast, Barry Cunliffe' s model ( 1984a; 1991 ), based on his work at Danebury, Hampshire, suggested a hierarchical Iron-Age society centred on hillforts directly influencing how hillforts and social organisation in the Cotswolds have been understood (Darvill1987; Saville 1984). Together these studies have set the agenda for how the 1st millennium BC in the region is regarded and their influence can be felt in more recent syntheses (e.g. Clarke 1993). Since 1984, however, our perception of Iron-Age societies has been radically altered. In particular, the role of hillforts as central places at the top of a hierarchical settlement pattern has been substantially challenged (Hill 1996). -

Download This Walk As A

Walk Six - Ledbury and Eastnor • 5.2 mile moderate ramble, one stile only • Disused canal, dismantled railway, town, village, views • OS Map - Malvern Hills and Bredon Hill (Explorer 190) The Route 1. Ledbury, Bye Street, opposite Market House. HR8 1BU. Return from either car park into Bye Street. Walk away from town centre past fire brigade and Brewery Inn. Find the Ledbury Town Trail information board in Queen’s Walk in the public gardens, formerly Ledbury Town Wharf. TR along the easy footpath, over the footbridge (below Masefield’s Knapp), for ⅔ mile, over road bridge to information board. Cross road. TL under railway bridge. In 40m TR over stile up R edge of orchard to crest, to find gap in top right corner. TR at path junction. Go through kissing gate and TR away from Frith Wood House. Follow path further R over railway in front of house to reach. 2. Knapp Lane. Bear R and immediately L along “No through road” at Upperfields. When reaching a seat, go ahead with fence on right, rather than descending to R, staying ahead downhill between green bench and Dog Hill Information Board at path junction. Descend steps past sub-station, take path ahead, into walled lane, to front of church. TL around church. TR along walled Cabbage Lane. TL past police station frontage. After 175m, cross road into Coneygree Wood. Climb into wood, up 19 wide steps, straight ahead, 16 narrow steps, curving L and R up stony terrain, six steps to path junction. Climb straight ahead. Bear R into field through walkers’ gate. -

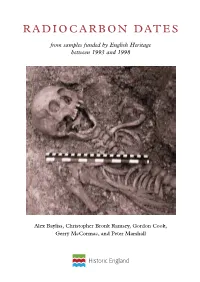

Radiocarbon Dates 1993-1998

RADIOCARBONDATES RADIOCARBONDATES RADIOCARBON DATES This volume holds a datelist of 1063 radiocarbon determinations carried out between 1993 and 1998 on behalf of the Ancient Monuments Laboratory of English Heritage. It contains supporting information about the samples and the sites producing them, a comprehensive bibliography, and two indexes for reference from samples funded by English Heritage and analysis. An introduction provides discussion of the character and taphonomy between 1993 and 1998 of the dated samples and information about the methods used for the analyses reported and their calibration. The datelist has been collated from information provided by the submitters of the samples and the dating laboratories. Many of the sites and projects from which dates have been obtained are now published, although developments in statistical methodologies for the interpretation of radiocarbon dates since these measurements were made may allow revised chronological models to be constructed on the basis of these dates. The purpose of this volume is to provide easy access to the raw scientific and contextual data which may be used in further research. Alex Bayliss, Christopher Bronk Ramsey, Gordon Cook, Gerry McCormac, and Peter Marshall Front cover:Wharram Percy cemetery excavations. (©Wharram Research Project) Back cover:The Scientific Dating Research Team visiting Stonehenge as part of Science, Engineering, and Technology Week,March 1996. Left to right: Stephen Hoper (The Queen’s University, Belfast), Christopher Bronk Ramsey (Oxford -

Further Prehistoric and Romano-British Activity at Poundbury Farm, Dorchester, Dorset

Further Prehistoric and Romano-British activity at Poundbury Farm, Dorchester, Dorset Online Publication Report WA ref: 60027.02 April 2019 wessexarchaeology © Wessex Archaeology Ltd 2019, all rights reserved. Portway House Old Sarum Park Salisbury Wiltshire SP4 6EB www.wessexarch.co.uk Wessex Archaeology Ltd is a company limited by guarantee registered in England, No. 1712772 and is a Registered Charity in England and Wales, No. 287786; and in Scotland, Scottish Charity No. SC042630. Registered Office: Portway House, Old Sarum Park, Salisbury, Wilts SP4 6EB Further Prehistoric and Romano-British activity at Poundbury Farm, Dorchester, Dorset By Kirsten Egging Dinwiddy with contributions by Phil Andrews, Alistair J. Barclay Dana Challinor, Nicholas Cooke, Phil Harding, L. Higbee, Lorraine Mepham, Jacqueline I. McKinley, Rachael Seager Smith, and Sarah F. Wyles and illustrations by Rob Goller, S.E. James and Nancy Dixon Wessex Archaeology 2019 List of Figures Figure 1 Site location and plan Figure 2 Site plan within surrounding archaeological setting Figure 3 Site plan detail Figure 4 Section and plan of urned cenotaph 9105 within grave 9104 Figure 5 a) Romano-British grave 9052 with burial remains 9051 and bone pin ON 7023 b) Durotrigian grave 9090 with burial remains 9089 and vessel ON 7024/5 Figure 6 a) Romano-British grave 9094 with burial remains 9093 and sheep ABG 9109 b) Romano-British grave 9125 with remains of decapitation burial 9124 and sheep ABG 7167 Figure 7 a) Romano-British grave 9126 with burial remains 9127, a coffin reconstruction -

Settlement Hierarchy and Social Change in Southern Britain in the Iron Age

SETTLEMENT HIERARCHY AND SOCIAL CHANGE IN SOUTHERN BRITAIN IN THE IRON AGE BARRY CUNLIFFE The paper explores aspects of the social and economie development of southern Britain in the pre-Roman Iron Age. A distinct territoriality can be recognized in some areas extending over many centuries. A major distinction can be made between the Central Southern area, dominated by strongly defended hillforts, and the Eastern area where hillforts are rare. It is argued that these contrasts, which reflect differences in socio-economic structure, may have been caused by population pressures in the centre south. Contrasts with north western Europe are noted and reference is made to further changes caused by the advance of Rome. Introduction North western zone The last two decades has seen an intensification Northern zone in the study of the Iron Age in southern Britain. South western zone Until the early 1960s most excavation effort had been focussed on the chaiklands of Wessex, but Central southern zone recent programmes of fieid-wori< and excava Eastern zone tion in the South Midlands (in particuiar Oxfordshire and Northamptonshire) and in East Angiia (the Fen margin and Essex) have begun to redress the Wessex-centred balance of our discussions while at the same time emphasizing the social and economie difference between eastern England (broadly the tcrritory depen- dent upon the rivers tlowing into the southern part of the North Sea) and the central southern are which surrounds it (i.e. Wessex, the Cots- wolds and the Welsh Borderland. It is upon these two broad regions that our discussions below wil! be centred. -

Flying High Showcasing Our Operations - Page 4

The Hills Group Newsletter intouch Issue 16 September 2008 Flying High Showcasing our operations - page 4 > Dave Bevan > Summer party > Edward Davis Hill Celebrates 25 years’ service Music Festival in memoriam Testing times We have been forced to scale back our house building operation due to the dramatic downturn in the housing market caused by the ‘credit crunch’ and resulting lack of mortgage availability. As a consequence we have sadly had to let go of a number of valued employees in the Property Division, which is not a decision that a company such as this has taken lightly. However, on behalf of the Company and the shareholders, I would like to thank those leaving for everything that they have done for us, and wish them all the luck and success for the future. Michael Hill Eventful Summer On a lighter note, you can read about a variety of events that the Company has by Michael Hill, Group Chief Executive been involved with, however there are two Farewell Ted that really stand out. The hugely successful It was with great sadness that many of us open day that the Waste Solutions division paid our respects in July to Ted Hill, older held at Lower Compton gave guests a real brother to Robert and Richard and grandson understanding of our recycling and disposal of the Company’s founder. The memorial operations both from the ground and the service was held on an aptly glorious day of air! (see page 4) The other was this year’s sunshine and was followed by a celebration Summer Party which took place as a music of his life that he would have been proud of! festival in July. -

A Comparative Study of Faunal Assemblages from British Iron Age Sites

Durham E-Theses A comparative study of faunal assemblages from British iron age sites Hambleton, Ellen How to cite: Hambleton, Ellen (1998) A comparative study of faunal assemblages from British iron age sites, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4646/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF FAUNAL ASSEMBLAGES FROM BRITISH IRON AGE SITES The copyright of this thesis rests witli the author. No quotation from it should be published without tlie written consent of the author and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Ellen Hambleton Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Archaeology University of Durham 1998 t 3 M 1999 STATEMENT OF COPYRIGHT The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without their prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged.