A Weak Thing: Iqbal Masih and the History of Child Labour in Pakistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IQBAL-MASIH.Pdf

IQBAL MASIH Cuando la juventud lucha por la justicia Eva Grijalvo, Eugenio Rodríguez y Javier Marijuán Edita e: Encuentro y Solidaridad Casa Emaús. C/ Uceda, 45. 28189 Torremocha de Jarama (Madrid) www.encuentroysolidaridad.net Telf. 918 48 55 48 [email protected] Abril 2020 Frente a la censura que suponen los precios de los libros, principal- mente ocasionada por el circuito comercial establecido en este sector, agradecemos a todos los que hacéis posible estas publicaciones la gratuidad de vuestra colaboración. El libro sigue siendo un artículo de primera necesidad en la cultura de los pueblos y debe ser tratado como tal y no como instrumento de negocio. Índice PRESENTACIÓN 5 FUNERALES EN HADDOQUEY 7 Una familia dividida 8 El recuerdo del niño esclavo 10 Los sollozos de Ehsan Ullah Khan 11 ¡DOCE MIL RUPIAS! 13 El intratable 15 De Shaukata Arshad 16 El reino de los intermediarios 17 La amenaza de la deuda 18 Un autómata hábil 19 Quejarse o callarse 20 MILLONES DE ESCLAVOS 22 El infierno de los ladrillos 23 El vulgar ganado humano 24 La aventura de Bhatta 25 Solo contra todos 26 La resistencia se organiza 27 El caso de Darshan Masih 29 De Bhatta al BLLF 31 Encadenados a tejer 32 Un nuevo objetivo: las alfombras 33 LUCHAR EN TODOS LOS FRENTES 34 Inmediata tragedia 35 Una herida medieval 35 El moderno Sjalkot 36 ¿Por qué un colegio? 37 Resistir a toda costa 38 Luchar en primer lugar 38 ¡PODER HABLAR; AL FIN! 40 Una victoria inesperada 41 Prisionero en Haddoquey 41 La primera huelga 42 Las buenas palabras de Munnawar Virk -

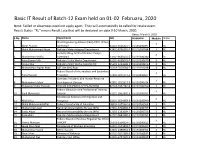

Basic IT Result of Batch 12

Basic IT Result of Batch-12 Exam held on 01-02 Februaru, 2020 Note: Failled or absentees need not apply again. They will automatically be called for retake exam. Result Status "RL" means Result Late that will be declared on date 9-10 March, 2020. Dated: March 5, 2020 S.No Name Department NIC Studentid Module Status Chief Engineering Adviser (CEA) /CFFC Office, 3 1 Abrar Hussain Islamabad 61101-5666325-7 VU191200097 RL 2 Malik Muhammad Ahsan Pakistan Meteorological Department 42401-8756355-7 VU191200184 3 RL Forestry Wing, M/O of Climate Change, 3 3 Muhammad Shafiq Islamabad 13101-3645024-5 VU191200280 RL 4 Asim Zaman Virk Pakistan Public Works Department 61101-4055043-7 VU191200670 3 RL 5 Rasool Bux Pakistan Public Works Department 45302-1434648-1 VU191200876 3 RL 6 Muhammad Asghar Khan S&T Dte GHQ Rwp 55103-7820568-7 VU191201018 3 RL Federal Board of Intermediate and Secondary 3 7 Tariq Hussain Education 37405-0231137-3 VU191200627 RL Overseas Pakistanis and Human Resource 3 8 Muhammad Zubair Development Division 42301-0211817-3 VU191200624 RL 9 Khaawaja Shabir Hussain CCD-VIII PAK PWD G-9/1 ISLAMABAD 82103-1652182-9 VU191200700 3 RL Federal Education and Professional Training 3 10 Sajid Mehmood Division 61101-1862402-9 VU191200933 RL Directorate General of Immigration and 3 11 Allah Ditta Passports 61101-6624393-9 VU191200040 RL 12 Malik Muhammad Afzal Federal Directorate of Education 38302-1075962-9 VU191200509 3 RL 13 Muhammad Asad National Accountability Bureau (KPk) 17301-6704686-5 VU191200757 3 RL 14 Sadiq Akbar National Accountability -

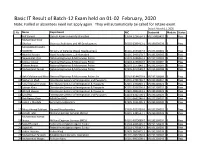

Basic IT Result of Batch-12 Exam Held on 01-02 February, 2020 Note: Failled Or Absentees Need Not Apply Again

Basic IT Result of Batch-12 Exam held on 01-02 February, 2020 Note: Failled or absentees need not apply again. They will automatically be called for retake exam. Dated: March 11, 2020 S.No Name Department NIC Studentid Module Status 1 Asif Sarwar Quaid I Azam University Islamabad 13504-2234564-3 VU170403412 3 Pass Muhammad Nasir 2 Ghafoor Overseas Pakistanis and HR Development 36502-1399412-1 VU191000539 3 Pass MUHAMMAD HARIS 3 NADEEM Ministry of Defence (Naval Headquarters) 61101-0153437-9 VU191200001 3 Pass 4 Abaid ul hassan Naval headquarters E_9 Islamabad 61101-2466178-7 VU191200002 3 Pass 5 Najeebullah Qazi National Highways & Motorways Police 43303-9448464-3 VU191200003 3 Pass 6 Attique Anwar National Highways & Motorways Police 16202-2236802-9 VU191200004 3 Pass 7 Zaheer Anwar National Highways & Motorways Police 82303-1177840-1 VU191200007 3 Pass 8 Muhammad Fayyaz National Highways & Motorways Police 37405-5210589-7 VU191200008 3 Pass 9 Hafiz Muhammad Nisar National Highways & Motorways Police Lhr 35202-6144679-9 VU191200009 3 Pass 10 Mehar Ali Shah Directorate General of Immigration and Passports 42401-1705785-7 VU191200014 3 Pass 11 Faisal Hussain Faruqi Directorate General of Immigration & Passports 42101-2334840-1 VU191200021 3 Pass 12 Salman Khan Directorate General of Immigration & Passports 42201-5266796-3 VU191200022 3 Pass 13 Ahmed Hassan Directorate General of Immigration & Passports 42301-0806113-1 VU191200023 3 Pass 14 Sandeep Directorate General of Immigration and Passports 44303-4342700-1 VU191200024 3 Pass 15 Rab -

Child Abuse in Craig Kielburger's

AEGAEUM JOURNAL ISSN NO: 0776-3808 CHILD ABUSE IN CRAIG KIELBURGER’S FREE THE CHILDREN: A YOUNG MAN FIGHTS AGAINST CHILD LABOR AND PROVES THAT CHILDREN CAN CHANGE THE WORLD DR. P. PANDIA RAJAMMAL FACULTY OF ENGLISH KALASALINGAM ACADEMY OF RESEARCH AND EDUCATION DEEMED TO BE UNIVERSITY A. SHARULAKSHMI III BA ENGLISH KALASALINGAM ACADEMY OF RESEARCH AND EDUCATION DEEMED TO BE UNIVERSITY Abstract: Craig Kielburger is a Canadian author, speaker, social entrepreneur and human rights activist in Canada. He was also a children’s rights activist. He is the co-founder of the organizations ‘Free the Children’Craig Kielbuger contacted many human rights organizations to speak about child labour during which he got a relationship with Alam Rahman. Both of them spoke about Iqbal Masih and child labour for more than two hours. Craig formed the Free the Children organisation with his friends. Then he did more actions to stop child labour in the world. KEY WORDS: social entrepreneur, human rights, activist, child labour and abuse Craig Kielburger was born on December 17, 1982 in Thronhill, Ontrio, Canada. His parents, Theresa and Fred Kielburger both of them were teachers. He had one elder brother, Marc Kielburger. Craig Kielburger studied at Blessed Scalabrini Catholic School, in Thornhill, Canada, and Mary Ward Catholic Secondary School in Scarborough, Toronto, Canada. In 2002, he started his higher studies in Peace and Conflict Studies in the Peace and Conflict Studies Program at University of Toronto. He completed Kellogg-Schulich - Executive MBA Program at New York University, in 2009, as the youngest graduate. Craig Kielburger is a Canadian author, speaker, social entrepreneur and human rights activist in Canada. -

Iqbal Masih Quotes

Iqbal masih quotes Continue In the mid-1990s, bright young people made a global impact on child slavery. Iqbal Masih's life was cut short only by a shy 13 years, but his powerful and eloquent speech encouraged thousands of bonded workers and child slaves to follow his example. It instills awareness and encourages education so that others can assert their rights and end injustice in sweatshops around the world. In 1983, Iqbal Masih was born in the impoverished community of Muridke outside Lahore, Pakistan. His family was financially burdened, and his father Saif Masih decided to leave when Iqbal was young. When he was 4 years old, Inaat's mother needed funds to pay for his older brother's wedding. Since the family was already in debt, she took a loan in Iqbal's name from a local businessman. However, when their debt became unpaid within two years, she was forced to loan Iqbal as a worker to pay off the debt. Iqbal became one of the many children's support workers in the carpet factory. Despite 14 hours six days a week, Iqbal never made enough money to pay off the debt, the cost of his apprenticeship, his tools, his meals, fines for his mistakes or growing interest. Although considered debt-bond he was indeed like millions of other children who were enslaved by their employers without hoping to earn their freedom. Kaba labour, child labour and slave labour were banned in Pakistan. However, he ran rampant because of the corrupt government and the police that lived off the bribes of local businessmen. -

Iqbal Masih " # $ % & ' SEARCH (

TRENDING: Iqbal Masih " # $ % & ' SEARCH ( REGION ! ACTIONS ! CENTURY ! GENDER ! WHO ARE SPECIAL CONTENT ! MORAL HEROES? IQBAL MASIH Posted by J Kile | Apr 20, 2011 | 20th Century, MoralHeroes is Economic, Male, Middle East, Social an archive of inspirational men, women, and youth throughout history that have sacri!ced for the betterment of others socially, physically, politically, economically, or environmentally. They are highlighted here to remind, encourage and inspire those of us who follow. In the mid-1990’s, a bright young youth made a global impact on child slavery. Iqbal Masih’s life was cut short just shy of 13 years but his powerful and eloquent speeches encouraged thousands of bonded RECENT laborers and child slaves to follow his example. He POSTS brought awareness and promoted education so that Dashra others could stand up for their rights and end the th injustice in sweatshops around the world. Manjhi Dec 14, In 1983, Iqbal Masih was born in the poor community 2015 | 20th of Muridke outside of Lahore, Pakistan. His family was Century, !nancially burdened, and his father Saif Masih Asia, Male, decided to leave when Iqbal was young. When he was Physical, Uncateg 4 years old, Iqbal’s mother Inayat needed funds to pay orized for his older brother’s wedding. Because the family was already in debt, she took out a loan in Iqbal’s Luigi name from a local businessman. However, when their Ciotti debt went unpaid for two years she was forced to Jun 21, “loan” Iqbal as a laborer to pay o" the debt. 2014 | 21st Century, Iqbal became one of the many child bonded laborers Economi c, at the carpet factory. -

CLAAS Annual Report 2017

Centre for legal Aid Assistance and Settlement Annual Report 2017 Published by: CENTRE FOR LEGAL AID ASSISTANCE & SETTLEMENT (CLAAS) 160- Hamza Town opposite Youhanabad, Ferozepur Road Lahore-Pakistan Tel: +92-42-35457317, +92-42-35457318 E-mail: [email protected] Website www.claasfamily.com Copyright: Centre for Legal Aid, Assistance & Settlement (CLAAS) - Pakistan Centre for legal Aid Assistance and Settlement Table of Content A Message of National Director 01 Executive Summary 02-06 Details of legal cases & Fact Finding Reports of CLAAS 07-75 Rehabilitation Centre (Apna Ghar & Safe House) 76-80 Feeding project 81-83 Advocacy and Lobbying 84-90 Community Development 90-99 Women Empowerment 100-104 Settlement of Survivors 105-109 Sunday School 110-112 Persecuted Christians 113 Law Open to Abuse 114-119 Other Key Activities of CLAAS 120-124 Acronyms 125- 130 CLAAS Coordinators, Board Members and Legal Advisors 131-132 Centre for legal Aid Assistance and Settlement Cases with subtitle Blasphemy Cases 1- State Vs Nabeel Masih 2-Zafar Bhatti Vs The State 3- Pastor Jadoon’s blasphemy case (Fact finding Report) 4- Mukhtar Masih was falsely involved in a blasphemy case (Fact Finding Report) 5- Ashfaq Masih a victim of blasphemy case (Fact finding Report) 6- Asif Stephen’s blasphemy case (Fact finding Report) 7- Iqbal Masih a mentally retarded (Fact finding Report) Sectarian hatred 1- The State VS Muhammad Ashraf Abduction, Forced Conversion and Forced Marriage 1- Elizabeth Vs Munir Ahmed etc 2- Saima Bibi Vs Ahmed Subhani 3- Sidra Javed