Celeste Blum Shulman 1949

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Englishvi2013.Pdf

Н.Мира, С.Хонгорзул, Ц.Бурмаа, Р.Ариунаа, Ж.Баясгалмаа ENGLISH VI Ерөнхий боловсролын 12 жилийн сургуулийн 10 дугаар ангийн сурах бичиг Боловсрол, шинжлэх ухааны яамны зөвшөөрлөөр хэвлэв. Хоёр дахь хэвлэл СУРГУУЛИЙН НОМЫН САНД олгов. БОРЛУУЛАХЫГ ХОРИГЛОНО. Упаанбаатар хот 2013 он DDC 372.65'077 A-618 English VI: Ерөнхий боловсролын 12 жилийн сургуулийн 10 дугаар ангийн сурах бичиг. /Мира Н., Хонгорзул С., Бурмаа Ц., Ариунаа P., Баясгалмаа Ж./ Ред. Мира Н. - УБ. 2013. - 216х Энэхүү сурах бичиг нь "Монгол Улсын Зохиогчийн эрх болон түүнд хамаарах эрхийн тухай" хуулиар хамгаалагдсан бөгөөд Боловсрол, шинжлэх ухааны яамнаас бичгээр авсан зөвшөөрлөөс бусад тохиолдолд цахим болон хэвлэмэл хэлбэрээр, бүтнээр эсхүл хэсэгчлэн хувилах, хэвлэх, аливаа хэлбэрээр мэдээллийн санд оруулахыг хориглоно. Сурах бичгийн талаарх аливаа санал, хүсэлтээ [email protected] хаягаар ирүүлнэ үү. © Боловсрол, шинжлэх ухааны яам ISBN 978-99929-3-454-9 CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 4-9 UNIT 1 FASHION AND BEAUTY 10-24 UNIT 2 SPORTS AND PHYSICAL HEALTH 25-39 UNIT 3 RELATIONSHIPS AND MORALITY 40-54 UNIT 4 LIVING IN THE GLOBAL WORLD 55-69 UNIT 5 MODERN TRAVEL 70-84 UNIT 6 FOOD SAFETY AND HEALTH 85-99 UNIT 7 WORLD OF ART 100-114 UNIT 8 ENVIRONMENT 115-129 UNIT 9 LEARNING AND EDUCATION 130-144 UNIT 10 COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGY 145-159 EXTENSION ACTIVITIES 160-180 GRAMMAR REFERENCE 181-189 DICTIONARY 190-193 TAPESCRIPTS 194-216 TABLE OF CONTENTS LESSONS STRUCTURES FUNCTIONS Shopping for clothes prefer / would like Talking about shops The way we dress look + adjective Describing appearance Talking about fashion Fashion trends used to + verb trends New images have something done Talking about images Checking personal Self-check Reviewing unit structures learning progress Describing sports Adventure sports so+ adjective; such + noun Giving preferences Present perfect (for repeated Talking about sports Sports events actions) vs. -

Reading the Irish Woman: Studies in Cultural Encounter and Exchange, 1714–1960

Reading the Irish Woman: Studies in Cultural Encounter and Exchange, 1714–1960 Meaney, Reading the Irish Woman.indd 1 15/07/2013 12:33:33 Reappraisals in Irish History Editors Enda Delaney (University of Edinburgh) Maria Luddy (University of Warwick) Reappraisals in Irish History offers new insights into Irish history, society and culture from 1750. Recognising the many methodologies that make up historical research, the series presents innovative and interdisciplinary work that is conceptual and interpretative, and expands and challenges the common understandings of the Irish past. It showcases new and exciting scholarship on subjects such as the history of gender, power, class, the body, landscape, memory and social and cultural change. It also reflects the diversity of Irish historical writing, since it includes titles that are empirically sophisticated together with conceptually driven synoptic studies. 1. Jonathan Jeffrey Wright, The ‘Natural Leaders’ and their World: Politics, Culture and Society in Belfast, c.1801–1832 Meaney, Reading the Irish Woman.indd 2 15/07/2013 12:33:33 Reading the Irish Woman Studies in Cultural Encounter and Exchange, 1714–1960 GerArdiNE MEANEY, MARY O’Dowd AND BerNAdeTTE WHelAN liVerPool UNIVersiTY Press Meaney, Reading the Irish Woman.indd 3 15/07/2013 12:33:33 reading the irish woman First published 2013 by Liverpool University Press 4 Cambridge Street Liverpool L69 7ZU Copyright © 2013 Gerardine Meaney, Mary O’Dowd and Bernadette Whelan The rights of Gerardine Meaney, Mary O’Dowd and Bernadette Whelan to be identified as the authors of this book have been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

33 CFR Ch. I (7–1–20 Edition)

Pt. 165 33 CFR Ch. I (7–1–20 Edition) maintain operative the navigational- eration in the area to be transited. safety equipment required by § 164.72. Failure of redundant navigational-safe- (b) Failure. If any of the navigational- ty equipment, including but not lim- safety equipment required by § 164.72 ited to failure of one of two installed fails during a voyage, the owner, mas- radars, where each satisfies § 164.72(a), ter, or operator of the towing vessel does not necessitate either a deviation shall exercise due diligence to repair it or an authorization. at the earliest practicable time. He or (1) The initial notice and request for she shall enter its failure in the log or a deviation and an authorization may other record carried on board. The fail- be spoken, but the request must also be ure of equipment, in itself, does not written. The written request must ex- constitute a violation of this rule; nor plain why immediate repair is imprac- does it constitute unseaworthiness; nor ticable, and state when and by whom does it obligate an owner, master, or the repair will be made. operator to moor or anchor the vessel. (2) The COTP, upon receiving even a However, the owner, master, or oper- spoken request, may grant a deviation ator shall consider the state of the and an authorization from any of the equipment—along with such factors as provisions of §§ 164.70 through 164.82 for weather, visibility, traffic, and the dic- a specified time if he or she decides tates of good seamanship—in deciding that they would not impair the safe whether it is safe for the vessel to pro- ceed. -

Graduate Catalog 2012–2013

Northeastern University Graduate Catalog 2012–2013 Contents THE UNIVERSITY 1 CURRICULUM AND GRADUATION REQUIREMENTS 49 BY PROGRAM General Admission and Transfer Credit 2 Academic Calendars 2 College of Arts, Media and Design 50 Regulations Applying to All Degree Programs 2 School of Architecture 50 Regulations Applying Only to PhD Programs 4 Art + Design 52 General Regulations and Requirements 4 School of Journalism 52 for NonDegree Certificate Programs Music 53 that Appear on the Transcript General Regulations and Requirements 4 D’Amore-McKim School of Business 55 for the Master’s Degree Master of Science 55 General Regulations and Requirements 5 Master of Business Administration 57 for the Certificate of Advanced Graduate Study Dual Degrees 59 General Regulations and Requirements 5 for the Doctoral Degree College of Computer and Information Science 62 General Regulations and Requirements 5 Computer Science 64 for Interdisciplinary Graduate Degrees Health Informatics 65 Information Assurance 67 Information for Entering Students 7 New Graduate Student Information 7 College of Engineering 68 International Student Information 7 Bioengineering 69 Academic Resources 8 Chemical Engineering 69 Information Services 10 Civil and Environmental Engineering 70 Campus Resources 12 Computer Systems Engineering 73 Electrical and Computer Engineering 75 College Expenses 20 Energy Systems 76 Tuition and Fees 20 Engineering Leadership 78 Student Refunds 20 Engineering Management 78 Financial Aid Assistance 21 Industrial Engineering 79 Bill Payment 23 -

676 Part 165—Regulated Naviga

Pt. 165 33 CFR Ch. I (7–1–15 Edition) shortage of personnel or lack of cur- 165.11 Vessel operating requirements (regu- rent nautical charts or maps, or publi- lations). cations; and 165.13 General regulations. (3) Any characteristics of the vessel Subpart C—Safety Zones that affect or restrict the maneuver- ability of the vessel, such as arrange- 165.20 Safety zones. ment of cargo, trim, loaded condition, 165.23 General regulations under-keel clearance, and speed.) (d) Deviation and authorization. The Subpart D—Security Zones owner, master, or operator of each tow- 165.30 Security zones. ing vessel unable to repair within 96 165.33 General regulations. hours an inoperative marine radar re- quired by § 164.72(a) shall so notify the Subpart E—Restricted Waterfront Areas Captain of the Port (COTP) and shall 165.40 Restricted waterfront areas. seek from the COTP both a deviation from the requirements of this section Subpart F—Specific Regulated Navigation and an authorization for continued op- Areas and Limited Access Areas eration in the area to be transited. Failure of redundant navigational-safe- FIRST COAST GUARD DISTRICT ty equipment, including but not lim- 165.T01–0125 Safety Zones; fireworks dis- ited to failure of one of two installed plays in Captain of the Port Long Island radars, where each satisfies § 164.72(a), Sound Zone. does not necessitate either a deviation 165.T01–0174 Regulated Navigation Areas and Safety Zone Tappan Zee Bridge Con- or an authorization. struction Project, Hudson River; South (1) The initial notice and request for Nyack and Tarrytown, NY. -

A Historical Phonology of English Donka Minkova

A Historical Phonology of English Donka Minkova EDINBURGH TEXTBOOKS ON THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE – ADVANCED A Historical Phonology of English Edinburgh Textbooks on the English Language – Advanced General Editor Heinz Giegerich, Professor of English Linguistics, University of Edinburgh Editorial Board Laurie Bauer (University of Wellington) Olga Fischer (University of Amsterdam) Rochelle Lieber (University of New Hampshire) Norman Macleod (University of Edinburgh) Donka Minkova (UCLA) Edgar W. Schneider (University of Regensburg) Katie Wales (University of Leeds) Anthony Warner (University of York) TITLES IN THE SERIES INCLUDE: Corpus Linguistics and the Description of English Hans Lindquist A Historical Phonology of English Donka Minkova A Historical Morphology of English Dieter Kastovsky Grammaticalization and the History of English Manfred Krug and Hubert Cuyckens A Historical Syntax of English Bettelou Los English Historical Sociolinguistics Robert McColl Millar A Historical Semantics of English Christian Kay and Kathryn Allan Visit the Edinburgh Textbooks in the English Language website at www. euppublishing.com/series/ETOTELAdvanced A Historical Phonology of English Donka Minkova © Donka Minkova, 2014 Edinburgh University Press Ltd 22 George Square, Edinburgh EH8 9LF www.euppublishing.com Typeset in 10.5/12 Janson by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Stockport, Cheshire, printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7486 3467 5 (hardback) ISBN 978 0 7486 3468 2 (paperback) ISBN 978 0 7486 3469 9 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 0 7486 7755 9 (epub) The right of Donka Minkova to be identifi ed as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Gabby Capuzzi Returns to Ohio State Women's Lacrosse As Associate

Gabby Capuzzi Returns To Ohio State Women’s Lacrosse As Associate Head Coach Gabby Capuzzi, who played at Ohio State from 2009-12 before serving as an assistant coach from 2012-14, is returning to Columbus to be the team’s associate head coach. Following her initial time at Ohio State, Capuzzi spent the last six seasons at Navy, where she served as an assistant coach from 2015-18 and associate head coach from 2019-20. Capuzzi’s primary role was coaching Navy’s defensive, while she also had an active role in recruiting. “Thank you to Gene Smith, Janine Oman and Amy Bokker for granting me the privilege to serve as the associate head coach for the women’s lacrosse program,” Capuzzi said. “As a proud alumna, I am extremely honored and grateful to be presented this opportunity at an institution that is so special and dear to my heart. My husband, Greg, and I are thrilled to return to our Buckeye roots! “I look forward to leading the women of Buckeye lacrosse alongside Coach Bokker and her staff. She is one of the most respected coaches in our game and I am excited for the chance to learn from her as I begin this journey under her leadership.” Capuzzi earned second-team All-American honors while playing at Ohio State, leading the Buckeyes with 42 goals, 52 draw controls, 38 ground balls and 31 caused turnovers in 2012. She ranks third in career draws with 166 and owns two of the program’s top 10 single-season records in that category. -

No. 16 USC Lacrosse Opens 2020 at Hofstra

2 0 2 0 U S C W O MEN ’ S L AC ross E 3 Conference Championships • 4 NCAA Appearances 3-time League Coach of the Year Lindsey Munday • 40 All-Conference Selections • 8 IWLCA All-Americans For release: Feb. 6, 2020 University of Southern California Sports Information • 3501 Watt Way • HER103 • Los Angeles, Calif. • (213) 740-8480 • Fax: (213) 740-7584 Assistant Director (Women’s Lacrosse): Jeremy Wu • Office:(213) 740-3807 • Cell: (213) 379-3977 • E-mail: [email protected] No. 16 USC Lacrosse Opens 2020 at Hofstra SCHEDULE AND RESULTS GAME #1 • Saturday, February 8 • 2 p.m. ET (11 a.m. PT) 0-0 Overall • 0-0 Pac-12 • IWLCA Rank: No. 16 No. 16 USC (0-0) at Hofstra (0-0) 0-0 Home • 0-0 Away • 0-0 Neutral James M. Shuart Stadium • Hempstead, N.Y. SERIES HISTORY: USC leads, 1-0 (1.000) • STREAK: W1 LAST MEETING: W, 15-10 (Feb. 9, 2019 • McAlister Field) FEBRUARY STREAM: Pride Production/Stretch Live 8 at Hofstra (StretchLive) 2 p.m. ET OPPONENT WEB: GoHofstra.com 15 Michigan (P12+) 12 p.m. 21 Boston College (P12+) 3 p.m. CROSSEXAMINATION 23 San Diego State (P12+) 12 p.m. • USC is ranked No. 16 in the IWLCA coaches poll; the 56th con- secutive week that the Trojans are ranked in the poll. MARCH • The Trojans are the defending Pac-12 champions. 6 Stanford * (P12+) 3 p.m. • Pac-12 coaches selected the Women of Troy to repeat as con- 8 California * (P12+) 12 p.m. ference champions in 2020 in a preseason poll. -

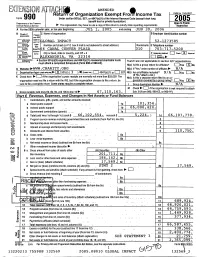

R F O T E F I I T I Urn O Rgan E on Xempt Roln Ncome Zat Ax

BffEO AUACH AMENDED Return of Organ ization Exempt Froln I ncome Tax OMB No 1545-004 Form Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except black lung 990 2005 benefit trust or private foundation) Intern nest of the Treasury DpEn f e ionic Internalal Revenue Service 0, The organization may have to use a copy of this ret urn to satisfy state reporting requirements 13ft$p Ct btt A For the 2005 calendar year , or tax year beginning JUL 1 , 2005 and ending JUN 30, 2006 B Check if C Name of organization D Employer identification number applicable Please use IRS Address label or =change print or LOBAL IMPACT 52-1273585 arm type Number and street or P box mail is not delivered to street address ) Room suite E ^NN, e See ( 0 if / Telephone number L;etum specific 66 CANAL CENTER PLAZA 310 703-717-5200 Final Instruc- O retum eons City or town, state or country , and ZIP + 4 F acccuneng memos L] Cash Q Accrual ded Other QXreturn EXANDRIA VA 22314 0 fy) ► QAp "tion • Section 501 (c)(3) organizations and 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trusts H and I are not applicable to section 527 organizations. must attach a completed Schedule A (Form 990 or 990 EZ). H( a ) Is this a g roup return for affiliates? 0 Yes M No CHARITY. ORG G Website : W • H(b) If 'Yes , enter number of affiliates ► N/A J Organization type (a>wkonhone 501(c)( 3 )I Onsert no )=4947(a)(1)or0527 H(c) Are all affiliates included? N /A DYes ONo ( if 'No a attachsepars a K Check here 10, = if the organization' s gross receipts are normally not more than $25 ,000 The H(d) Is this a eparateate return filed by an or- organization need not file a return with the IRS, but it the organization chooses to file a return, be ganization covered by a g rou p rulin g? =Yes [ No sure to file a complete return Some states require a complete return . -

College Board Test Scores

Thur 06/27 - Meadowood Regional Park Thurs 06/27 - St. Paul's School Field 1 Field 2 Field 3 Field 4 Field 6 Field 7 Turf 1 Turf 2 Upper Grass Boys Command Girls Command Girls Command Boys Command Baltimore vs Washington New England Girls vs Baltimore vs CONNY South vs New England DC Southwest Girls 1:00 PM 1:00 PM 1:00 Boys Command Girls Command Girls Command Boys Command Philadelphia vs Long Philadelphia vs Midwest Washington DC vs South Upstate NY vs New Jersey Island 2:15 PM 2:15 2:15 PM 2:15 Girls Command Boys Command Girls Command Boys Command New Jersey vs Long West vs Midwest West Girls vs Upstate NY CONNY vs Southwest Island 3:30 PM 3:30 3:30 PM 3:30 Fri 06/28 - Meadowood Regional Park Fri 06/28 - St. Paul's School Field 1 Field 2 Field 3 Field 4 Field 6 Field 7 Turf 1 Turf 2 Upper Grass Girls Highlight Boys Highlight Boys Highlight Boys Highlight Girls Highlight Girls Highlight New Jersey Girls vs Long Midwest Boys vs Philadelphia Boys vs New Jersey Boys vs New Washington DC Girls vs Baltimore vs CONNY Island Washington DC Long Island England South 8:30 AM 8:30 AM 8:30 Girls Highlight Girls Highlight Boys Highlight Boys Highlight Boys Highlight Girls Highlight New England vs Philadelphia vs Midwest South vs West Southwest vs Upstate NY Baltimore vs CONNY West vs Upstate NY Southwest 9:45 AM 9:45 9:45 AM 9:45 Boys Command Girls Command Girls Command Boys Command Boys Command Girls Command Baltimore vs New Southwest vs Baltimore New Jersey vs CONNY Long Island vs Midwest CONNY vs Philadelphia South vs Long Island England 11:00 -

Former NU Cadet Leading the Way in Iraq

THE LANCE Liberty Battalion Army ROTC Newsletter, Fall 2004 www.rotc.neu.edu 2LT Lisa Kirby preparing for Convoy Operations in Baghdad, Iraq Former NU Cadet Leading the Way in Iraq By Cadet Jeffrey Barrett The Global War on Terrorism and Operation Iraqi One of her planned convoy trips was cancelled due to a Freedom continue, cadets entering the Army are high level of intelligence showing Improvised Explosive prepared and ready for possible deployment sometime in Devices, or IED’s, along the route. A different convoy their future career. This time came quickly for 2LT Lisa that went as planned brought 2LT Kirby into Baghdad Kirby, who is now serving in a signal platoon under the where she had her first glimpse of the city and its all too 10th Mountain Division stationed at Camp Victory, Iraq. apparent juxtaposition of elegant palaces and the relative 2LT Kirby graduated from Northeastern University in filth and poverty seen on the average Iraqi street. December 2003, and became a gold bar recruiter while Through her service in Iraq, 2LT Kirby is now a waiting to report for her Officer Basic Course (OBC). Combat Veteran and has earned her combat patch with She reported to the Signal Corps OBC at Ft. Gordon, GA the 10th Mountain Division. We all remember the on March 17th 2004. Upon completion of OBC, she shining example she set for all of us as a cadet and reported to Ft. Drum, NY, serving as a Platoon Leader newly commissioned officer while at Northeastern. We with the 10th Mountain Division. -

Longstreth Sporting Goods and Women's Professional Lacrosse

Longstreth Sporting Goods and Women’s Professional Lacrosse League Announce Partnership Leading Sporting Goods Retailer partners with new women’s lacrosse league. SPRING CITY, Pa. – September 1, 2017 - Longstreth Sporting Goods and the Women’s Professional Lacrosse League (WPLL) are pleased to announce a partnership and the launch of an exclusive online store for WPLL apparel. The store will be hosted on www.longstreth.com. Former UWLX commissioner Michele DeJuliis announced the launch of the WPLL on June 1, and will act as the league’s founder and CEO. DeJuliis has since appointed Jen Adams as the league’s first-ever commissioner. The WPLL will boast five teams in its inaugural summer 2018 season: Baltimore Brave, New England Command, New York Fight, Philadelphia Fire and Upstate Pride. The league will also include a development program to train future professional players. The WPLL is committed to both advancing the sport of women’s lacrosse through providing athletes with professional opportunities. Longstreth has been a leader in women’s sporting goods and is proud to support the new league to help advance women’s lacrosse. Both organizations share common goals and commitment to supporting and growing the game of women’s lacrosse. Founded and managed by players for players, Longstreth is dedicated to bringing the best products and services to the women’s lacrosse athlete at any level. Longstreth will host an online store for the exclusive official WPLL branded apparel. From t-shirts and sweatshirts to hats and decals, the line of products will offer something for every player, parent, and fan.