Constitutional Combat: Is Fighting a Form of Free Speech? the Ultimate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce

U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND COMMERCE December 8, 2016 TO: Members, Subcommittee on Commerce, Manufacturing, and Trade FROM: Committee Majority Staff RE: Hearing entitled “Mixed Martial Arts: Issues and Perspectives.” I. INTRODUCTION On December 8, 2016, at 10:00 a.m. in 2322 Rayburn House Office Building, the Subcommittee on Commerce, Manufacturing, and Trade will hold a hearing entitled “Mixed Martial Arts: Issues and Perspectives.” II. WITNESSES The Subcommittee will hear from the following witnesses: Randy Couture, President, Xtreme Couture; Lydia Robertson, Treasurer, Association of Boxing Commissions and Combative Sports; Jeff Novitzky, Vice President, Athlete Health and Performance, Ultimate Fighting Championship; and Dr. Ann McKee, Professor of Neurology & Pathology, Neuropathology Core, Alzheimer’s Disease Center, Boston University III. BACKGROUND A. Introduction Modern mixed martial arts (MMA) can be traced back to Greek fighting events known as pankration (meaning “all powers”), first introduced as part of the Olympic Games in the Seventh Century, B.C.1 However, pankration usually involved few rules, while modern MMA is generally governed by significant rules and regulations.2 As its name denotes, MMA owes its 1 JOSH GROSS, ALI VS.INOKI: THE FORGOTTEN FIGHT THAT INSPIRED MIXED MARTIAL ARTS AND LAUNCHED SPORTS ENTERTAINMENT 18-19 (2016). 2 Jad Semaan, Ancient Greek Pankration: The Origins of MMA, Part One, BLEACHERREPORT (Jun. 9, 2009), available at http://bleacherreport.com/articles/28473-ancient-greek-pankration-the-origins-of-mma-part-one. -

Cage Fury Fighting Championships Thriving After Some Early Hits

Cage Fury Fighting Championships thriving after some early hits DAVID WEINBERG Staff Writer | Posted: Tuesday, August 4, 2015 10:30 am ATLANTIC CITY Lightweight fighter Stephen Regman pressed his forearm against Jordan Stiner's windpipe last month at Borgata Hotel Casino & Spa and squeezed as if he were trying to empty a bottle of suntan lotion. Stiner, from Hatfield, Pennsylvania, struggled to break the hold, but eventually tapped his hand against his thigh, prompting referee Liam Kerrigan to halt the scheduled threeround fight. Cage Fury thriving after some early hits Regman, of Watchung, climbed to the top of the 6 foothigh cage and flexed his biceps while a capacity Cage Fury Fighting Championships CEO crowd of 2,400 at Borgata's Events Center cheered. Rob Haydak watches the monitor at a fight last year at Borgata. Last month, Cage Fury A few feet away, Cage Fury Fighting Championships put on its 50th fight card. "Everything boils president and CEO Rob Haydak surveyed the scene down to the fighters, and I think we've done and smiled. a great job of finding the best talent and The fight was part of a special card for Vinelandbased guys who have good followings," Haydak CFFC, the area's only professional mixed martial arts said. organization. The show was CFFC's 50th, marking another milestone in what has been a remarkable comeback from disaster. "What they've been able to do is very impressive," New Jersey Athletic Control Board official Nick Lembo said Saturday. "Along with (New Yorkbased) Ring of Combat (which stages fights at Tropicana Casino and Resort), Cage Fury is the best regional promotion in North America." Up until a few years ago, it appeared as if CFFC would fall 45 shows short of 50. -

Rules Shooto

Rules Shooto tournaments are held under a strict and comprehensive set of rules. Its objectives are to protect the athlete and to ensure dynamic and fair fights. A distinction is made between amateur (Class C), semi-pro (Class B) and professional (Class A) rules. Depending on the class, certain techniques are prohibited and the fight duration is adapted as well. The different classes in Shooto make it possible for athletes to improve in a controlled and safe environment. Weight classes Featherweight – 60kg Lightweight – 65kg Welterweight – 70kg Middleweight – 76kg Light-Heavyweight – 83kg Cruiserweight – 91kg Heavyweight – +91kg Rules – Brief Version — A pro fight consists of three 5-minute rounds with one-minute breaks in between. Amateurs fight two 3-minute rounds, semi-pros fight two 5-minute rounds. — A referee oversees the fight in the ring and controls adherence of the rules. — Three judges score the fight according to effective strikes, takedowns and aggressivity/activity whilst standing and dominant positions, submission attempts and defense whilst being on the floor. — A victory can be scored by judges decision, knock-out (KO), technical knock-out (TKO), by submission or by referee- or doctor-stoppage. — Fighters are divided by weight classes. — Before the fight, fighters have to attend a medical check and the doctor needs to approve the fight. — Protective equipment (gloves, cup, mouthguard) are mandatory. Amateurs (C-class) are allowed to fight with headgear and shinguards. — Illegal fouls are headbutts, elbow-strikes, biting, groin attacks of any kind, attacks on the back or the back of the head, attacks on small joints, attacks on the eyes or ears and further actions which oppose a fair fight. -

Outside the Cage: the Campaign to Destroy Mixed Martial Arts

OUTSIDE THE CAGE: THE CAMPAIGN TO DESTROY MIXED MARTIAL ARTS By ANDREW DOEG B.A. University of Central Florida, 2010 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2013 © 2013 Andrew Doeg ii ABSTRACT This is an early history of Mixed Martial Arts in America. It focuses primarily on the political campaign to ban the sport in the 1990s and the repercussions that campaign had on MMA itself. Furthermore, it examines the censorship of music and video games in the 1990s. The central argument of this work is that the political campaign to ban Mixed Martial Arts was part of a larger political movement to censor violent entertainment. Connections are shown in the actions and rhetoric of politicians who attacked music, video games and the Ultimate Fighting Championship on the grounds that it glorified violence. The political pressure exerted on the sport is largely responsible for the eventual success and widespread acceptance of MMA. The pressure forced the sport to regulate itself and transformed it into something more acceptable to mainstream America. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................................... vi INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 Historiography ........................................................................................................................... -

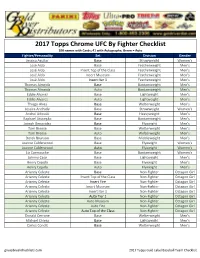

2017 Topps UFC Checklist

2017 Topps Chrome UFC By Fighter Checklist 100 names with Cards; 41 with Autographs; Green = Auto Fighter/Personality Set Division Gender Jessica Aguilar Base Strawweight Women's José Aldo Base Featherweight Men's José Aldo Insert Top of the Class Featherweight Men's José Aldo Insert Museum Featherweight Men's José Aldo Insert Iter 1 Featherweight Men's Thomas Almeida Base Bantamweight Men's Thomas Almeida Auto Bantamweight Men's Eddie Alvarez Base Lightweight Men's Eddie Alvarez Auto Lightweight Men's Thiago Alves Base Welterweight Men's Jessica Andrade Base Strawweight Women's Andrei Arlovski Base Heavyweight Men's Raphael Assunção Base Bantamweight Men's Joseph Benavidez Base Flyweight Men's Tom Breese Base Welterweight Men's Tom Breese Auto Welterweight Men's Derek Brunson Base Middleweight Men's Joanne Calderwood Base Flyweight Women's Joanne Calderwood Auto Flyweight Women's Liz Carmouche Base Bantamweight Women's Johnny Case Base Lightweight Men's Henry Cejudo Base Flyweight Men's Henry Cejudo Auto Flyweight Men's Arianny Celeste Base Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Top of the Class Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Fire Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Museum Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Iter 1 Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Tier 1 Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Museum Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Fire Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Top of the Class Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Donald Cerrone Base Welterweight -

Ufc Fight Night Features Exciting Middleweight Bout

® UFC FIGHT NIGHT FEATURES EXCITING MIDDLEWEIGHT BOUT ® AND THE ULTIMATE FIGHTER FINALE ON FOX SPORTS 1 APRIL 16 Two-Hour Premiere of THE ULTIMATE FIGHTER: TEAM EDGAR VS. TEAM PENN Follows Fights on FOX Sports 1 LOS ANGELES, CA – Two seasons of THE ULTIMATE FIGHTER® converge on FOX Sports 1 on Wednesday, April 16, when UFC FIGHT NIGHT®: BISPING VS. KENNEDY features THE ULTIMATE FIGHTER NATIONS welterweight and middleweight finals, the coaches’ fight and an exciting headliner between No. 5-ranked middleweight Michael Bisping (25-5) and No. 8- ranked Tim Kennedy (17-4). FOX Sports 1 carries the preliminary bouts beginning at 5:00 PM ET, followed by the main card at 7:00 PM ET from Quebec City, Quebec, Canada. Immediately following UFC FIGHT NIGHT: BISPING VS. KENNEDY is the two-hour season premiere of THE ULTIMATE FIGHTER®: TEAM EDGAR vs. TEAM PENN (10:00 PM ET), highlighting 16 middleweights and 16 light heavyweights battling for a spot on the team of either former lightweight champion Frankie Edgar or two-division champion BJ Penn. UFC on FOX analyst Brian Stann believes the headliner between Bisping and Kennedy is a toss-up. “Kennedy has one of the best top games in mixed martial arts and he’s showcased his knockout power in his last fight against Rafael Natal. Bisping is one of the best all-around mixed martial artists in the middleweight division. Every time people start to count him out, he comes in and wins fights.” In addition to the main event between Bisping and Kennedy, UFC FIGHT NIGHT consists of 12 more thrilling matchups including THE ULTIMATE FIGHTER NATIONS Team Canada coach Patrick Cote (20-8) and Team Australia coach Kyle Noke (20-6-1) in an exciting welterweight bout. -

Maestro Sin Man Ho Escuela WU De Taichi Chuan

REVISTA BIMESTRAL DE ARTES MARCIALES Nº23 año IV MAESTRO SIN MAN HO Escuela WU de Taichi Chuan Origen Histórico de los Katas de Karate Gasshuku & Taikai Nihon Kobudo 2014 Entrevista al maestro José Antonio Cantero Aikido: Entrevista al maestro Ricard Coll Conferencia internacional de Taijiquan en Handan Primer examen oficial de la Federación Japonesa de Iaidô (ZNIR) en España De Taijitsu a Nihon Taijitsu Sumario 4 Noticias 6 Entrevista al maestro Sin Man Ho. Escuela WU de Taichi Chuan [Por Sebastián González] [email protected] 16 Primer examen oficial de la Federación Japonesa de Iaidô (ZNIR) en España www.elbudoka.es [Por José Antonio Martínez-Oliva Puerta] Dirección, redacción, 20 Nace Martial Tribes administración y publicidad: [Por www.martialtribes.com] 22 El sistema Taiji [Por Zi He (Jeff Reid)] Editorial “Alas” 26 De Taijitsu a Nihon Taijitsu C/ Villarroel, 124 [Por Pau-Ramon Planellas] 08011 Barcelona Telf y Fax: 93 453 75 06 Entrevista al maestro José Antonio Cantero [email protected] 32 www.editorial-alas.com [Por Francisco J. Soriano] 38 El ecosistema y la biodiversidad de Capoeira La dirección no se responsabiliza de las opiniones [Por Cristina Martín] de sus colaboradores, ni siquiera las comparte. La publicidad insertada en “El Budoka 2.0” es responsa- 40 VIª Gala Benéfica de Artes Marciales bilidad única y exclusiva de los anunciantes. [Por Andreu Martínez] No se devuelven originales remitidos espontáneamente, ni se mantiene correspondencia 44 Origen Histórico de los Katas de Karate sobre los mismos. [Por Pedro Hidalgo] Director: José Sala Comas 52 Las páginas del DNK: El bastón en el Kenpo Full Defense Jefe de redacción: Jordi Sala F. -

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. April 22, 2019 to Sun. April 28, 2019 Monday

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. April 22, 2019 to Sun. April 28, 2019 Monday April 22, 2019 4:00 PM ET / 1:00 PM PT 6:00 AM ET / 3:00 AM PT Rock Legends Smart Travels Europe Amy Winehouse - Despite living a tragically short life, Amy had a significant impact on the music Out of Rome - We leave the eternal city behind by way of the famous Apian Way to explore the industry and is a recognized name around the world. Her unique voice and fusion of styles left a environs of Rome. First it’s the majesty of Emperor Hadrian’s villa and lakes of the Alban Hills. musical legacy that will live long in the memory of everyone her music has touched. Next, it’s south to the ancient seaport of Ostia, Rome’s Pompeii. Along the way we sample olive oil, stop at the ancient’s favorite beach and visit a medieval hilltop town. Our own five star villa 4:30 PM ET / 1:30 PM PT is a retreat fit for an emperor. CMA Fest Thomas Rhett and Kelsea Ballerini host as more than 20 of your favorite artists perform their 6:30 AM ET / 3:30 AM PT newest hits, including Carrie Underwood, Blake Shelton, Keith Urban, Jason Aldean, Luke Bryan, Rock Legends Dierks Bentley, Thomas Rhett, Chris Stapleton, Kelsea Ballerini, Jake Owen, Darius Rucker, Broth- Pearl Jam - Rock Legends Pearl Jam tells the story of one of the world’s biggest bands, featuring ers Osborne, Lauren Alaina and more. insights from music critics and showcasing classic music videos. -

Cultivating Identity and the Music of Ultimate Fighting

CULIVATING IDENTITY AND THE MUSIC OF ULTIMATE FIGHTING Luke R Davis A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2012 Committee: Megan Rancier, Advisor Kara Attrep © 2012 Luke R Davis All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Megan Rancier, Advisor In this project, I studied the music used in Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) events and connect it to greater themes and aspects of social study. By examining the events of the UFC and how music is used, I focussed primarily on three issues that create a multi-layered understanding of Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) fighters and the cultivation of identity. First, I examined ideas of identity formation and cultivation. Since each fighter in UFC events enters his fight to a specific, and self-chosen, musical piece, different aspects of identity including race, political views, gender ideologies, and class are outwardly projected to fans and other fighters with the choice of entrance music. This type of musical representation of identity has been discussed (although not always in relation to sports) in works by past scholars (Kun, 2005; Hamera, 2005; Garrett, 2008; Burton, 2010; Mcleod, 2011). Second, after establishing a deeper sense of socio-cultural fighter identity through entrance music, this project examined ideas of nationalism within the UFC. Although traces of nationalism fall within the purview of entrance music and identity, the UFC aids in the nationalistic representations of their fighters by utilizing different tactics of marketing and fighter branding. Lastly, this project built upon the above- mentioned issues of identity and nationality to appropriately discuss aspects of how the UFC attempts to depict fighter character to create a “good vs. -

Printed in the Clovis News- Pages Past Is Compiled Journal

SATURDAY,JAN. 27, 2018 Inside: 75¢ Trump denies Times report. — Page 4B Vol. 89 ◆ No. 259 SERVING CLOVIS, PORTALES AND THE SURROUNDING COMMUNITIES EasternNewMexicoNews.com Courthouse evacuated ❏ A suspicious package near the law library was reported. BY THE STAFF OF THE NEWS “suspicious characteris- to determine (the pack- tics.” Agencies including age’s) origin,” Waller said. CLOVIS — Law Clovis police and firefight- Waller said a bomb threat enforcement evacuated the ers closed off the roads in called into the courthouse Curry County Courthouse one block each direction around 10:30 a.m. Friday and closed off a two-block from Seventh and Mitchell was still under investiga- perimeter near downtown streets. tion, but that threat was Clovis several hours Friday Officials with Cannon evaluated in the morning afternoon before a bomb Air Force Base’s Explosive and did not result in the squad determined a suspi- Ordnance Disposal team building’s evacuation. cious package found out- were on scene with a bomb side the Dan Buzzard Law disposal robot before 4 Officials did not immedi- Library was not an explo- p.m. and responders ately respond to questions sive device. remained after 6 p.m. to about whether Friday's Sheriff Wesley Waller conduct a secondary search incidents may have been said the package, reported of the area after evaluating connected to reports early around 2 p.m. outside the the package. this week about "telephon- building near Eighth and “We will now conduct an ic threats" that had resulted Mitchell streets, featured investigation and attempt in three arrests. Staff photo: Tony Bullocks Above: An airman with Cannon Air Force Base's Explosive Ordnance Disposal team begins work to help determine the contents of a suspicious package found near the Curry County Courthouse on Friday afternoon. -

Fox Sports Highlights – 3 Things You Need to Know

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Wednesday, Sept. 17, 2014 FOX SPORTS HIGHLIGHTS – 3 THINGS YOU NEED TO KNOW NFL: Philadelphia Hosts Washington and Dallas Meets St. Louis in Regionalized Matchups COLLEGE FOOTBALL: No. 4 Oklahoma Faces West Virginia in Big 12 Showdown on FOX MLB: AL Central Battle Between Tigers and Royals, Plus Dodgers vs. Cubs in FOX Saturday Baseball ******************************************************************************************************* NFL DIVISIONAL MATCHUPS HIGHLIGHT WEEK 3 OF THE NFL ON FOX The NFL on FOX continues this week with five regionalized matchups across the country, highlighted by three divisional matchups, as the Philadelphia Eagles host the Washington Redskins, the Detroit Lions welcome the Green Bay Packers, and the San Francisco 49ers play at the Arizona Cardinals. Other action this week includes the Dallas Cowboys at St. Louis Rams and Minnesota Vikings at New Orleans Saints. FOX Sports’ NFL coverage begins each Sunday on FOX Sports 1 with FOX NFL KICKOFF at 11:00 AM ET with host Joel Klatt and analysts Donovan McNabb and Randy Moss. On the FOX broadcast network, FOX NFL SUNDAY immediately follows FOX NFL KICKOFF at 12:00 PM ET with co-hosts Terry Bradshaw and Curt Menefee alongside analysts Howie Long, Michael Strahan, Jimmy Johnson, insider Jay Glazer and rules analyst Mike Pereira. SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 21 GAME PLAY-BY-PLAY/ANALYST/SIDELINE COV. TIME (ET) Washington Redskins at Philadelphia Eagles Joe Buck, Troy Aikman 24% 1:00PM & Erin Andrews Lincoln Financial Field – Philadelphia, Pa. MARKETS INCLUDE: Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Washington, Miami, Raleigh, Charlotte, Hartford, Greenville, West Palm Beach, Norfolk, Greensboro, Richmond, Knoxville Green Bay Packers at Detroit Lions Kevin Burkhardt, John Lynch 22% 1:00PM & Pam Oliver Ford Field – Detroit, Mich. -

Pete Suazo Utah Athletic Commission Unified Rules Of

PETE SUAZO UTAH ATHLETIC COMMISSION GOVERNOR’S OFFICE OF ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT P.O. Box 146950 60 East South Temple, 3rd Floor Salt Lake City, UT 84114-6950 Office: 801-538-8876 Fax: 801-708-0849 UNIFIED RULES OF PROFESSIONAL MIXED MARTIAL ARTS 1. Definitions “Mixed martial arts” means unarmed combat involving the use, subject to any applicable limitations set forth in these Unified Rules and other regulations of the applicable Commission, of a combination of techniques from different disciplines of the martial arts, including, without limitation, grappling, submission holds, kicking and striking. “Unarmed Combat” means any form of competition in which a blow is usually struck which may reasonably be expected to inflict injury. “Unarmed Combatant” means any person who engages in unarmed combat. “Commission” means the applicable athletic commission or regulatory body overseeing the bouts, exhibitions or competitions of mixed martial arts. 2. Weight Divisions Except with the approval of the Commission, or its executive director, the classes for mixed martial arts contests or exhibitions and the weights for each class shall be: Strawweight up to 115 pounds Flyweight over 115 pounds to 125 Bantamweight over 125 to 135 pounds Women's Bantamweight over 125 to 135 pounds Featherweight over 135 to 145 pounds Lightweight over 145 to 155 pounds Welterweight over 155 to 170 pounds Middleweight over 170 to 185 pounds Light Heavyweight over 185 to 205 pounds Heavyweight over 205 to 265 pounds Super Heavyweight over 265 pounds In non-championship fights, there shall be allowed a 1 pound weigh allowance. In championship fights, the participants must weigh no more than that permitted for the relevant weight division.