Baseline Assessment Report -Tai Po District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minutes of 1008 Meeting of the Town

Minutes of 1008th Meeting of the Town Planning Board held on 23.3.2012 Present Permanent Secretary for Development Chairman (Planning and Lands) Mr. Thomas Chow Mr. K.Y. Leung Mr. Walter K.L. Chan Mr. B.W. Chan Ms. Maggie M.K. Chan Mr. Felix W. Fong Ms. Anna S.Y. Kwong Professor Paul K.S. Lam Mr. Maurice W.M. Lee Mr. Timothy K.W. Ma Professor P.P. Ho Professor Eddie C.M. Hui Dr. C.P. Lau Ms. Julia M.K. Lau Dr. W.K. Lo Mr. Roger K.H. Luk Ms. Anita W.T. Ma Professor S.C. Wong Dr. W.K. Yau 2 - Deputy Director of Lands Mr. Jeff Y.T. Lam Deputy Director of Environmental Protection Mr. Benny Y.K. Wong Principal Assistant Secretary (Transport) Transport and Housing Bureau Mr. Fletch W.W. Chan Director of Planning Mr. Jimmy C.F. Leung Deputy Director of Planning/District Secretary Miss Ophelia Y.S. Wong Absent with Apologies Mr. Stanley Y.F. Wong Mr. Raymond Y.M. Chan Mr. Y.K. Cheng Dr. James C.W. Lau Professor Edwin H.W. Chan Mr. Rock C.N. Chen Dr. Winnie S.M. Tang Mr. Clarence W.C. Leung Mr. Laurence L.J. Li Ms. Pansy L.P. Yau Mr. Stephen M.W. Yip Assistant Director (2), Home Affairs Department Mr. Eric K.S. Hui 3 - In Attendance Assistant Director of Planning/ Board Mr. C.T. Ling Chief Town Planner/Town Planning Board Ms. Christine K.C. Tse (a.m.) Senior Town Planner/Town Planning Board Mr. -

Minutes of 1054 Meeting of the Town Planning Board Held on 14.3.2014

CONFIDENTIAL [downgraded on 28.3.2014] Minutes of 1054th Meeting of the Town Planning Board held on 14.3.2014 Sha Tin, Tai Po and North District Agenda Item 6 Consideration of the Draft Ping Chau Development Permission Area Plan No. DPA/NE-PC/B (TPB Paper No. 9580) [Closed meeting. The meeting was conducted in Cantonese.] 1. The following representatives of Planning Department (PlanD) were invited to the meeting at this point: Mr C.K. Soh - District Planning Officer/Sha Tin, Tai Po & North (DPO/STN), PlanD Mr David Y.M. Ng - Senior Town Planner/New Plans (STN) (STP/NP(STN)), PlanD 2. The Chairman extended a welcome and invited the representatives of PlanD to brief Members on the Paper. 3. Members noted that a replacement page of the Paper was tabled at the meeting. With the aid of a Powerpoint presentation, Mr C.K. Soh, DPO/STN, briefed Members on the details of the draft Ping Chau Development Permission Area (DPA) Plan No. DPA/NE-PC/B as detailed in the Paper and covered the following main points: Location and Physical Characteristics (a) the Ping Chau DPA (the Area), with an area of about 29 hectares, - 2 - covered part of Ping Chau Island in Mirs Bay, the easternmost outlying island of Hong Kong; (b) a large part of Ping Chau Island was included in the Plover Cove (Extension) Country Park and was surrounded by the Tung Ping Chau Marine Park designated in 2001 for its diverse coral communities and marine ecosystem; (c) Ping Chau Island was accessible by sea with a public pier located near Tai Tong at the northeastern part of the island. -

Tai Po Country

Occupational Safety & Health Council, Hong Kong SAR, China Certifying Centre for Safe Community Programs On behalf of the WHO Collaborating Centre on Community Safety Promotion, Department of Public Health Sciences Division of Social Medicine, Karolinska Institute, Sweden Name of the Community: Tai Po Country: Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China Number of inhabitants: 291,371 Programme started year: 2002 International Safe Communities Network Membership: Designation year: 2005 (Re- designation Year: 2010) Info address on www for the Programme: wwww.tpshc.org For further information contact: Name: Dr Augustine Lam (Tai Po Safe Community Coordinator) Cluster Co-coordinator (Community Partnership) Institution: New Territories East Cluster, Hospital Authority Address: Room 1/2/25, 1/Fl. Block A, Alice Ho Miu Ling Nethersole Hospital, 11 Chuen On Road, Tai Po, New Territories Country: Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China Phone (country code included): (852) 2689-2147 Fax: (852) 2689-2161 E-mail: [email protected] Info address on www for the institution (or community as a whole): www.tpshc.org The Tai Po Safe and Healthy City Project covers the following safety promotion activities: For the age group Children 0-14 years: Promotional Pamphlets on Childhood Injury Prevention Department of Health has structured seminars and produced various pamphlets and printing materials to educate parents on childhood injury prevention. Topics include “Love your Child, Prevent Injuries (0-1 year old/1-3 years old/3-5 years old)”, “Love your Child, Prevent Accidents (Home Safety)”, etc. The pamphlets and posters can also be downloaded from the website of Department of Health for the convenience of the general public. -

Minutes of 1216Th Meeting of the Town Planning Board Held on 10.1.2020

Minutes of 1216th Meeting of the Town Planning Board held on 10.1.2020 Present Professor S.C. Wong Vice-Chairperson Mr Lincoln L.H. Huang Mr H.W. Cheung Mr Sunny L.K. Ho Mr Stephen H.B. Yau Dr F.C. Chan Mr David Y.T. Lui Mr Peter K.T. Yuen Mr Philip S.L. Kan Dr Lawrence W.C. Poon Mr K.K. Cheung Mr Wilson Y.W. Fung Dr C.H. Hau Mr Thomas O.S. Ho Mr Alex T.H. Lai Dr Lawrence K.C. Li Mr Stephen L.H. Liu - 2 - Professor T.S. Liu Mr Franklin Yu Mr L.T. Kwok Mr Daniel K.S. Lau Ms Lilian S.K. Law Mr K.W. Leung Professor John C.Y. Ng Dr Jeanne C.Y. Ng Professor Jonathan W.C. Wong Chief Traffic Engineer (Kowloon) Transport Department Mr David C.V. Ngu Chief Engineer (Works), Home Affairs Department Mr Paul Y.K. Au Deputy Director of Environmental Protection (1) Environmental Protection Department Mr Elvis W.K. Au Director of Lands Mr Thomas C.C. Chan Director of Planning Mr Raymond K.W. Lee Deputy Director of Planning/District Secretary Miss Fiona S.Y. Lung Absent with Apologies Permanent Secretary for Development Chairperson (Planning and Lands) Ms Bernadette H.H. Linn Mr Ivan C.S. Fu Dr Frankie W.C. Yeung Miss Winnie W.M. Ng - 3 - Ms Sandy H.Y. Wong Mr Stanley T.S. Choi Mr Ricky W.Y. Yu In Attendance Assistant Director of Planning/Board Ms Lily Y.M. Yam Chief Town Planner/Town Planning Board Ms April K.Y. -

For Information on 15 December 2009 Legislative Council Panel On

For information On 15 December 2009 Legislative Council Panel on Environmental Affairs Banning of Commercial Fishing in Marine Parks Purpose At the meeting on 23 November 2009, Members requested the Administration to provide the following information for Members’ reference- Background of the Proposal 2. Hong Kong has a diverse assemblage of marine organisms. The marine parks are set up to protect and conserve our marine environment for the purposes of conservation, education and recreation. 3. In order to better protect and conserve the marine resources in our marine parks, we propose to ban commercial fishing in marine parks. In fact, many overseas countries, including New Zealand and the Philippines, have set up marine protection areas in which fishing activities are prohibited. 4. This measure will not only improve the marine ecology and environment in the protected areas, but also that of the adjacent waters, enriching the fishery resources, and bringing benefits to the marine ecology and environment as a whole. Consultation 5. In the long run, banning of commercial fishing in marine parks could effectively improve the local marine ecology and environment. There are currently four marine parks in Hong Kong, with a total area of around 2,410 hectares, covering around 2% of Hong Kong waters. Should the policy initiative of banning commercial fishing in marine parks be implemented, fishing activities could still be carried out outside marine parks. In order to better understand how this proposal would affect the fishermen who are conducting fishing activities in marine parks, over the past few months, we have been consulting the relevant fishermen associations and fishermen to learn more about their concerns, as well as their suggestions. -

13Ed255d2c1d986b82976b6106

0 1 Editorial Dear readers, We are delighted to present to you the latest collection of our students’ writings. Each year, we try to gather a wide range of different writing topics of different levels for you to enjoy and learn from. At this school, we have always believed that reading is one of the most important skills to improve language ability. For this reason, we have always tried to motivate our students to read more. Apart from immersing your range of vocabulary and exposing you to different types of writings, reading is also a form of entertainment. It stimulates imagination and creativity. Good stories may make you laugh, cry or care about the characters. We cannot stress to you enough how important and for reading is. Whenever you have free time, whether it is 5 minutes or 20 minutes, pick up this copy of Evergreen or another book and immerse yourself in joy of reading. Supervisor: Mr. Tsui Chun Cheung Editors: Ms. Ellce Li Mr. Kenny Ho Ms. Melody Lee Designer: Ms. Janet Yip 2 MY MONSTER P.7 – 14 ANIMAL RIDDLE P.15 – 19 MY TOY P.20 MY FRIEND P.21 IN THE PARK P.22 – 23 WARDROBE P.24 MY FAMILY P.26 – 33 MY FRIEND P.34 – 38 MY PET P.39 – 43 SHOPPING CENTRE P.44 DOING HOUSEWORK P.45 – 47 JOURNAL P.48 – 49 RULES P.50 MY DIARY OF THE CAMPING TRIP P.52 – 54 MY BEST FRIEND P.55 – 59 ABOUT MYSELF P.60 – 65 MY WEEKENDS P.66 – 67 MY BIRTHDAY PARTY P.68 P.J. -

Jockey Club Age-Friendly City Project Action Plan for Tai Po District

Jockey Club Age-friendly City Project Action Plan for Tai Po District CUHK Jockey Club Institute of Ageing October 2016 1. Background By 2041, one third of the overall population in Hong Kong will be the older people, which amount to 2.6 million. The demographic change will lead to new or expanded services, programs and infrastructure to accommodate the needs of older people. Creating an age-friendly community will benefit people of all ages. Making cities age-friendly is one of the most effective policy approaches for responding to demographic ageing. In order to proactively tackle the challenges of the rapidly ageing population, The Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust is implementing the Jockey Club Age- friendly City (“JCAFC”) Project in partnership with four gerontology research institutes in Hong Kong. The project aims to build momentum in districts to develop an age-friendly community, recommend a framework for districts to undertake continual improvement, as well as arouse public awareness and encourage community participation. Eight districts have been piloted. The CUHK Jockey Club Institute of Ageing is responsible for Sha Tin and Tai Po District. 2. Profile of Tai Po District Tai Po is located in the northeast part of the New Territories. Topographically, Tai Po is encircled on three sides by the mountain. The valley areas and basins become the major grounds for human settlements. Tai Po is one of the new towns in Hong Kong since 1979. Historically, Tai Po is a market town famous for trading of agricultural and fishing products. The old market was located at the coastal plains where Tai Po River and Lam Tsuen River cross. -

Hong Kong's Old Villages

METUPLACES JFA FROM 2018/2 THE PAST LOST IN NEW TOWNS: DOI:METU 10.4305/METU.JFA.2017.2.5 JFA 2018/2 197 (35:2)HONG 197-220 KONG’S OLD VILLAGES PLACES FROM THE PAST LOST IN NEW TOWNS: HONG KONG’S OLD VILLAGES Terry Van DIJK*, Gerd WEITKAMP** Received: 24.02.2016; Final Text: 06.03.2017 INTRODUCTION Keywords: Heritage; new town; master plan; planning; urbanisation. Awareness of Hong Kong’s built heritage and its value is considered to have begun to increase around the time of the end of British rule. The change in Hong Kong’s sovereignty in 1997 prompted a search for its own identity, because while no longer under British rule, and not being nor becoming entirely Chinese, it was not immediately obvious what the emerging Hong Kong should put forward as its cultural identity. The question since that time has also become economically pertinent, as Hong Kong has developed into a major Asian tourist destination. As cultural tourism could be developed into one of the pillars of Hong Kong’s leisure economy, debate emerged on its identity and the built heritage it reflects. This article addresses the popular assumption that before 1997, heritage had been of little interest to Hong Kong’s governments, as articulated by Yung and Chan (2011), Henderson (2001) and Cheung (1999). This negligence was explained by the fact that Hong Kong’s population was growing exponentially through several waves of large-scale immigration, while being under an obviously temporary British government. This resulted in a heterogeneous population (Henderson, 2001) which had just migrated there and was more concerned about access to housing, employment and transportation than the history of the lands they were about to inhabit (Yung and Chan, 2011, 459). -

立法會cb(2)808/18-19(01)號文件

立法會CB(2)808/18-19(01)號文件 附件一 Annex 1 Annex 1 Technical Guideline on Prevention and Control of Biting Midges Biting midges are fly belonging to the family Ceratopogonidae. Adults are about 1-4 mm long, dark-coloured with female possessing piercing and sucking mouthparts. 2. Larvae are aquatic or semi-aquatic, being found in damp places or in mud. Adults can usually hatch in about 40 days but cooler weather will lengthen the process to about several months. Adults rest in dense vegetation and sometimes shady places. They fly in zigzag patterns and seldom fly more than 100 meter from their breeding grounds; however, dispersal by wind is possible. Nevertheless, wind over 5 .6 kilometers/hour and temperatures below 10°C inhibit flying. In fact they are so fragile that cool and dry weather will shorten their longevity. Only female bite but they rarely do it indoors. Since they have short mouthparts, they cannot bite through clothing and so exposed body parts are more often attacked. 3. Irritation caused by bites of these midges can last for days, or even weeks. Scratching aggravates the pruritus and may lead to bacterial infection and slow healing sores. However, biting midges are not considered important vectors of human diseases locally. 4. Different genera ofCeratopogonidae vary in their habits and biology. The control methodology for different genera should be tailor-made so as to enhance the effectiveness of the control measures. Almost all Culicoides ()!f[~/!111) tend to be crepuscular or nocturnal feeders while Lasiohelea (@~)!ill) are diurnal and bite human at daytime. -

TOWN PLANNING BOARD Minutes of 478Th Meeting of the Rural And

TOWN PLANNING BOARD Minutes of 478th Meeting of the Rural and New Town Planning Committee held at 2:30 p.m. on 7.12.2012 Present Director of Planning Chairman Mr. Jimmy C.F. Leung Professor Edwin H.W. Chan Dr. C.P. Lau Ms. Anita W.T. Ma Dr. W.K. Yau Dr. Wilton W.T. Fok Mr. Lincoln L.H. Huang Ms. Janice W.M. Lai Mr. H.F. Leung Chief Traffic Engineer/New Territories West, Transport Department Mr. W.C. Luk Assistant Director (Environmental Assessment), Environmental Protection Department Mr. K.F. Tang - 2 - Assistant Director/New Territories, Lands Department Ms. Anita K.F. Lam Deputy Director of Planning/District Secretary Miss Ophelia Y.S. Wong Absent with Apologies Mr. Timothy K.W. Ma (Vice-chairman) Mr. Rock C.N. Chen Dr. W.K. Lo Professor K.C. Chau Mr. Ivan C.S. Fu Ms. Christina M. Lee Chief Engineer (Works), Home Affairs Department Mr. Frankie W.P. Chou In Attendance Assistant Director of Planning/Board Ms. Christine K.C. Tse Chief Town Planner/Town Planning Board Mr. Jerry Austin Town Planner/Town Planning Board Miss Hannah H.N. Yick - 3 - Agenda Item 1 Confirmation of the Draft Minutes of the 477th RNTPC Meeting held on 23.11.2012 [Open Meeting] 1. The draft minutes of the 477th RNTPC meeting held on 23.11.2012 were confirmed without amendments. Agenda Item 2 Matters Arising [Open Meeting] 2. The Secretary reported that there were no matters arising. - 4 - Sha Tin, Tai Po and North District [Ms. Jacinta K.C. -

Transcript of the Hearing Held on 14 July 2018

INDEPENDENT REVIEW COMMITTEE ON HONG KONG’S FRANCHISED BUS SERVICE Day 06 Page 1 Page 3 1 Saturday, 14 July 2018 1 I may read you. It is a letter from the Tai Po District 2 (9.00 am) 2 Council, replying to the committee. Dated 23 May 2018. 3 EVIDENCE FROM TAI PO DISTRICT COUNCIL: MS WONG PIK KUI, 3 The letter states that: 4 MR CHAN CHO LEUNG, MR YAM KAI BONG, MR CHAN SIU KUEN, DR LAU 4 "Among the records, the Tai Po District Council, its 5 CHEE SING 5 Committees and Working Groups had only discussed about 6 (given in Cantonese; transcription of the simultaneous 6 the traffic accident that occurred on Tai Po Road near 7 interpretation) 7 Tai Po Mei on 10 February 2018." 8 CHAIRMAN: Good morning. We welcome the representatives of 8 Is that correct? 9 the Tai Po District Council. We thank them for 9 MS WONG PIK KUI: Yes. Yes. 10 responding to our invitation by coming today to assist 10 MS MAGGIE WONG: So do I take it that according to your 11 us with their evidence. 11 records, the discussion, you were only able to retrieve 12 I'm going to ask Ms Wong to begin by posing 12 documents in relation to the Tai Po accident, but not 13 questions to the representatives. If Ms Wong wishes one 13 the other two accidents? 14 of the other representatives of the council to respond 14 MS WONG PIK KUI: Yes. For the accident on 15 to a particular question, please feel free to identify 15 10 February 2018, we had a special meeting to 16 that person, and that person can then deal with the 16 discuss it. -

Replies to Initial Written Questions Raised by Finance Committee Members in Examining the Estimates of Expenditure 2020-21 Home

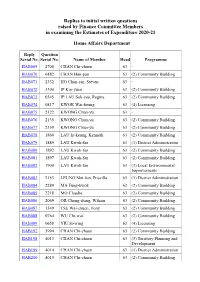

Replies to initial written questions raised by Finance Committee Members in examining the Estimates of Expenditure 2020-21 Home Affairs Department Reply Question Serial No. Serial No. Name of Member Head Programme HAB069 2700 CHAN Chi-chuen 63 - HAB070 0482 CHAN Han-pan 63 (2) Community Building HAB071 2332 HO Chun-yin, Steven 63 - HAB072 3300 IP Kin-yuen 63 (2) Community Building HAB073 0345 IP LAU Suk-yee, Regina 63 (2) Community Building HAB074 0817 KWOK Wai-keung 63 (4) Licensing HAB075 2122 KWONG Chun-yu 63 - HAB076 2135 KWONG Chun-yu 63 (2) Community Building HAB077 2359 KWONG Chun-yu 63 (2) Community Building HAB078 1860 LAU Ip-keung, Kenneth 63 (2) Community Building HAB079 1889 LAU Kwok-fan 63 (1) District Administration HAB080 1892 LAU Kwok-fan 63 (2) Community Building HAB081 1897 LAU Kwok-fan 63 (2) Community Building HAB082 1900 LAU Kwok-fan 63 (3) Local Environmental Improvements HAB083 2153 LEUNG Mei-fun, Priscilla 63 (1) District Administration HAB084 2289 MA Fung-kwok 63 (2) Community Building HAB085 2218 MO Claudia 63 (2) Community Building HAB086 2049 OR Chong-shing, Wilson 63 (2) Community Building HAB087 1349 TSE Wai-chuen, Tony 63 (2) Community Building HAB088 0764 WU Chi-wai 63 (2) Community Building HAB089 0658 YIU Si-wing 63 (4) Licensing HAB197 3994 CHAN Chi-chuen 63 (2) Community Building HAB198 4013 CHAN Chi-chuen 63 (5) Territory Planning and Development HAB199 4014 CHAN Chi-chuen 63 (1) District Administration HAB200 4015 CHAN Chi-chuen 63 (2) Community Building Reply Question Serial No. Serial No.