1:21-Cv-02693 Document #: 1 Filed: 05/18/21 Page 1 of 106 Pageid #:1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May/June 2020 Edition

VOL. 38, NO. 2 MAY 2020 ® Published by Delmarva Poultry Industry, Inc. I Georgetown, Delaware Outstanding Growers: Let’s Give Them Their Due In regretfully canceling the Booster Banquet, we complicated one of the most thrilling and inspiring things does: recognizing DPI another class of Outstanding Growers, selected by their chicken companies based upon their performance and a list of criteria including environmental stewardship, cooperation, attitude, and achievement. Our communications manager, James Fisher, was in the middle of visiting this year’s 10 chosen growers to take photos, videos, and hear their stories when the COVID-19 crisis put a quick halt to that travel. And with the banquet on ice, we missed an opportunity for members to acknowledge and DPI’s ® congratulate these hardworking farmers. INSIDE THIS ISSUE I Outstanding Grower: Let’s Give But an outstanding grower doesn’t need a silver bowl and a long Them Their Due / 17 & 21 walk across the stage of the Wicomico Youth & Civic Center to be I Is My Barking Farm Dog a an inspiration to us all. Please join in congratulating these Legal Nuisance? / 22 DPI outstanding growers! I MDA Offers FastTrack Grants for Hauling Litter / 24 Steve Brittingham, Millsboro, Delaware - Mountaire Farms I What Poultry IBV Might Teach Us About COVID-19 / 26 & 28 Craig Davidson, Frankford, Delaware - Amick Farms I HPAI Detected in Turkeys Donald Howard, Crisfield, Maryland - Tyson Foods in South Carolina / 30 I How Fast Does Water Move In John & Patrick Kelley, Pocomoke City, Maryland - Mountaire -

Infectious Bronchitis: Evolving Strategies for an Evolving Virus

POULTRY HIGHLIGHTS OF A ROUNDTABLE DISCUSSION HEALTH T O D A Y ® INFECTIOUS BRONCHITIS: EVOLVING STRATEGIES VIRUS FOR AN EVOLVING AUGUST 2019 • WASHINGTON, DC INFECTIOUS BRONCHITIS: EVOLVING STRATEGIES FOR AN EVOLVING VIRUS WELCOME T he evolution of infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) is a continuing challenge for poultry producers and veterinarians. In broilers, this highly infectious coronavirus can present in its traditional form as respiratory disease, predisposing birds to secondary bacterial infections. Relatively newer on the scene are potentially deadly nephropathogenic IBV strains. In any form, IBV impairs animal welfare and is an important source of economic loss for poultry producers. Vaccination is key to IBV control. Although homologous vaccines are considered to be the JON SCHAEFFER, DVM, PHD most effective, development of a new vaccine for every new IBV strain that emerges is difficult Director, Poultry Technical Services, Zoetis to impossible. Finding an effective existing vaccine or combination of vaccines that will [email protected] zoetisus.com/foodsafety cross-protect is a worthwhile venture, but there’s no guarantee of success. Zoetis recently hosted a roundtable featuring renowned IBV experts as well as practitioners who shared their knowledge about IBV. These proceedings are highlights from the conversation and are provided with the hope they will help the industry achieve better control of IBV, improve animal welfare and minimize IBV’s financial burden. Sponsored by POULTRY HIGHLIGHTS OF A ROUNDTABLE DISCUSSION HEALTH T O D A Y ® TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 IBV TRENDS...................................................................... 4 2 IBV DETECTION................................................................ 5 3 IBV IN BROILER BREEDERS.............................................. 6 4 IBV AND IMMUNITY.......................................................... 6 5 IMPACT OF NO ANTIBIOTICS EVER................................. -

United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois Eastern Division

Case: 1:18-cv-00702 Document #: 1 Filed: 01/30/18 Page 1 of 131 PageID #:1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION US FOODS, INC. Plaintiff, v. TYSON FOODS, INC.; TYSON CHICKEN, INC.; TYSON BREEDERS, INC.; TYSON COMPLAINT POULTRY, INC.; PILGRIM’S PRIDE CORPORATION; KOCH FOODS, INC.; JCG FOODS OF ALABAMA, LLC; JCG FOODS OF GEORGIA, LLC; KOCH MEAT CO., INC.; SANDERSON FARMS, INC.; Jury Trial Demanded SANDERSON FARMS, INC. (FOOD DIVISION); SANDERSON FARMS, INC. (PRODUCTION DIVISION); SANDERSON FARMS, INC. (PROCESSING DIVISION); HOUSE OF RAEFORD FARMS, INC.; MAR-JAC POULTRY, INC.; PERDUE FARMS, INC.; PERDUE FOODS, LLC; WAYNE FARMS, LLC; FIELDALE FARMS CORPORATION; GEORGE’S, INC.; GEORGE’S FARMS, INC.; SIMMONS FOODS, INC.; SIMMONS PREPARED FOODS, INC.; O.K. FOODS, INC.; O.K. FARMS, INC.; O.K. INDUSTRIES, INC.; PECO FOODS, INC.; HARRISON POULTRY, INC.; FOSTER FARMS, LLC; FOSTER POULTRY FARMS; CLAXTON POULTRY FARMS, INC.; MOUNTAIRE FARMS, INC.; MOUNTAIRE FARMS, LLC; MOUNTAIRE FARMS OF DELAWARE, INC.; and AGRI STATS, INC., Defendants. Case: 1:18-cv-00702 Document #: 1 Filed: 01/30/18 Page 2 of 131 PageID #:2 I. NATURE OF THE ACTION ...................................................................................................1 A. Defendants illegally agreed to curtail the supply of chicken. ...............................................1 B. Defendants illegally agreed to manipulate and artificially inflate the Georgia Dock. ..........5 II. PARTIES ..................................................................................................................................8 -

“Don't Just Switch from Beef to Chicken”

“Don’t Just Switch from Beef to Chicken” A Presentation by Karen Davis, PhD, President of United Poultry Concerns Photo by Frank Johnston, The Washington Post A study published in 2014 by the National Academy of Sciences, “Land, irrigation water, greenhouse gas, and reactive nitrogen burdens of meat, eggs, and dairy production in the United States,” says “beef” is worse for the environment than “chicken.” Without disputing the data specific to this study, I do dispute the implication that the answer to cattle pollution is to eat more poultry or any other animal product. The environmental impacts of global animal production are vast, complicated, and worsening. The poultry industry in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States is a microcosm of the global expansion of the poultry industry and its baleful effect on land, air, water, and human and animal wellbeing. “The new complex will include a processing plant, hatchery, feed mill and related operations.” It isn’t just a chicken house here, another one there. Instead you see five, ten or more long, low buildings, each housing thousands of unseen birds, lined up side by side along Route 50 and Route 13 and all over the back roads of Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia. North of us, on Route 13, a giant Perdue chicken slaughter plant (“processing complex”) fronts the highway and a little farther on a Tyson complex. Every day truckloads of chickens travel these roads to the slaughter plants. For decades a conflict has simmered between the environmentalists and the Delmarva poultry industry, periodically spawning reports by The Washington Post and other media about the burden of chicken manure and slaughterhouse waste on the Chesapeake Bay and the “legacy of lenience” that lets industry do as it pleases. -

According to the Lawsuit

Case 1:19-cv-02521-ELH Document 1 Filed 08/30/19 Page 1 of 77 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF MARYLAND JUDY JIEN, 2007 Keith Circle, Apt. 8 Springdale, AR 72764 CIVIL ACTION NO. 1:19-CV-2521 KIEO JIBIDI, and CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT 317 Berry Street, Apt. 203 Springdale, AR 72764 JURY TRIAL DEMANDED ELAISA CLEMENT, 2781 Alton Avenue, Apt. B Springdale, AR 72764. on behalf of themselves and all others similarly situated, Plaintiffs, v. PERDUE FARMS, INC, 31149 Old Ocean City Road Salisbury, MD 21804 County of Residence: Wicomico County PERDUE FOODS LLC, 31149 Old Ocean City Road Salisbury, MD 21804 County of Residence: Wicomico County TYSON FOODS, INC., 2200 West Don Tyson Parkway Springdale, AR 72762 TYSON PREPARED FOODS, INC., 2200 West Don Tyson Parkway Springdale, AR 72762 THE HILLSHIRE BRANDS COMPANY, 2200 West Don Tyson Parkway Springdale, AR 72762 TYSON FRESH MEATS, INC., 2200 West Don Tyson Parkway Springdale, AR 72762 Case 1:19-cv-02521-ELH Document 1 Filed 08/30/19 Page 2 of 77 TYSON PROCESSING SERVICES, INC., 2200 West Don Tyson Parkway Springdale, AR 72762 TYSON REFRIGERATED MEATS, INC., 2200 West Don Tyson Parkway Springdale, AR 72762 KEYSTONE FOODS, LLC, 905 Airport Road, Suite 400 West Chester, Pennsylvania 19380 EQUITY GROUP EUFAULA DIVISION, LLC, 57 Melvin Clark Road Bakerhill, AL 36027 EQUITY GROUP - GEORGIA DIVISION, LLC, 7200 Highway 19 P.O. Box 369 Camilla, GA 31730 EQUITY GROUP KENTUCKY DIVISION, LLC, 2294 KY Highway 90 W Albany, KY 42602 PILGRIM’S PRIDE CORPORATION, 1770 Promontory Circle, Greeley, CO 80634 PILGRIM’S PRIDE CORPORATION OF WEST VIRGINIA, INC., 129 Potomac Avenue Moorfield, WV 26836 SANDERSON FARMS, INC., 127 Flynt Road Laurel, MS 39443 SANDERSON FARMS, INC. -

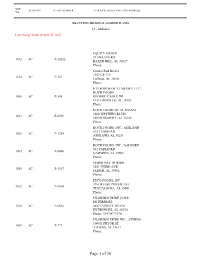

Page 1 of 36 NPIP

NPIP. SUBPART PLANT NUMBER PARTICIPANTS NAME AND ADDRESS NO. MEAT-TYPE CHICKEN SLAUGHTER PLANTS 64 - Alabama Last change made on July 22, 2021 EQUITY GROUP 57 MELVIN RD 1013 6C P-20322 BAKER HILL, AL 36027 Phone: Golden Rod Broiler 2352 CR 719 1434 6C P-341 Cullman, AL 35056 Phone: JCG FOODS OF ALABAMA, LLC, KOCH FOODS 1008 6C P-548 GEORGE CAGLE DR COLLINSVILLE, AL 35961 Phone: KOCH FOODS OF ALABAMA 3500 WESTERN BLVD 1011 6C P-6529 MONTGOMERY, AL 36108 Phone: KOCH FOODS, INC., ASHLAND 515 TYSON RD 1002 6C P-1254 ASHLAND, AL 36251 Phone: KOCH FOODS, INC., GADSDEN 501 PADEN RD 1003 6C P-6666 GADSDEN, AL 35903 Phone: MARSHALL DURBIN 3301 THIRD AVE 1050 6C P-1307 JASPER, AL 35502 Phone: PECO FOODS, INC 3701 REESE PHIFER AVE 1012 6C P-6504 TUSCALOOSA, AL 35401 Phone: PILGRIM'S PRIDE CORP., ENTERPRISE 1010 6C P-6638 4847 COUNTY RD 636 ENTERPRISE, AL 36330 Phone: 334-347-7330 PILGRIM'S PRIDE INC., ATHENS 1004 E PRYOR ST 1009 6C P-227 ATHENS, AL 35611 Phone: PILGRIM'S PRIDE INC., BOAZ Page 1 of 36 NPIP. SUBPART PLANT NUMBER PARTICIPANTS NAME AND ADDRESS NO. MEAT-TYPE CHICKEN SLAUGHTER PLANTS 64 - Alabama Last change made on July 22, 2021 PILGRIM'S PRIDE INC., BOAZ GOLD KIST ST 1005 6C P-413 BOAZ, AL 35957 Phone: PILGRIM'S PRIDE, INC., GUNTERVILLE 3500 LAKE GUNTERVILLE PARK 1006 6C P-192 DR GUNTERVILLE, AL 35976 Phone: PILGRIM'S PRIDE, INC., RUSSELLVILLE 1007 6C P-17500 COUNTY RD 244 RUSSELLVILLE, AL 35653 Phone: TYSON FOODS, INC., ALBERTVILLE 997 6C P-559 PO BOX 1097 ALBERTVILLE, AL 35950 Phone: TYSON FOODS, INC., BLOUNTSVILLE 1000 6C P-6 67240 MAIN ST BLOUNTSVILLE, AL 35031 Phone: TYSON FOODS, INC., BOAZ BOAZ 1004 6C P-12621 BOAZ, AL 35956 Phone: Wayne Farms 808 ROSS CLARK CIR 1027 6C P-7342 DOTHAN, AL 36303 Phone: WAYNE FARMS LLC, ALBERTVILLE 1033 6C P-1317 MCDONALD AVE ALBERTVILLE, AL 35950 Phone: WAYNE FARMS LLC, DECATUR RATLIFF IND. -

Mountaire Releases Statement Regarding Millsboro Facility Consent Decree Agreement

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT MICHAEL W. TIRRELL EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT OF PROCESSING OPERATIONS MOUNTAIRE FARMS INC. CONTACT PHONE: (302) 934-4151 E-MAIL: [email protected] Mountaire Releases Statement Regarding Millsboro Facility Consent Decree Agreement MILLSBORO, DE. (June 4, 2018) Mountaire Farms of Delaware, Inc. signed a Consent Decree agreed to by both Mountaire and DNREC, after careful discussion and negotiation which will resolve all issues raised in lawsuits brought by the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control in the Delaware Superior Court and in the Federal District Court for the District of Delaware. These lawsuits, and the Consent Decree that will resolve them, were brought on by an unfortunate upset condition in our Millsboro facility’s wastewater treatment plant. This upset condition – which we voluntarily reported to DNREC – caused us to exceed our permit limits. While the worst aspects of the upset condition were brought under control very quickly, our plant is not back to operating at the level we want, and will not be until after both interim corrective measures and long-term system upgrades, in total costing $60 million, are completed. The Consent Decree accomplishes three objectives: First, we are committed to having the long term system upgrades completed in just 24 months, and DNREC has agreed to expedite the permitting process to help us accomplish this objective. This cooperation is critical if we are to meet this accelerated time frame. Once these system upgrades are complete, we believe our wastewater treatment plant will be the most modern in Sussex County, if not all of Delaware. -

Maplevale Farms, Inc., Individually and on Case No

Case: 1:16-cv-08637 Document #: 1 Filed: 09/02/16 Page 1 of 116 PageID #:1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS Maplevale Farms, Inc., individually and on Case No. ________________ behalf of all others similarly situated, CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT Plaintiff, vs. Koch Foods, Inc., JCG Foods of Alabama, LLC, JCG Foods of Georgia, LLC, Koch Meats Co., Inc., Tyson Foods, Inc., Tyson Chicken, Inc., Tyson Breeders, Inc., Tyson Poultry, Inc., Pilgrim’s Pride Corporation, Perdue Farms, Inc., Sanderson Farms, Inc., Sanderson Farms, Inc. (Foods Division), Sanderson Farms, Inc. (Production Division), Sanderson Farms, Inc. (Processing Division), Wayne Farms, LLC, Mountaire Farms, Inc., Mountaire Farms, LLC, Mountaire Farms of Delaware, Inc., Peco Foods, Inc., Foster Farms, LLC, House of Raeford Farms, Inc., Simmons Foods, Inc., Fieldale Farms Corporation, George’s, Inc., George’s Farms, Inc., O.K. Foods, Inc., O.K. Farms, Inc., and O.K. Industries, Inc. Defendants. 492538 Case: 1:16-cv-08637 Document #: 1 Filed: 09/02/16 Page 2 of 116 PageID #:2 Table of Contents I. NATURE OF ACTION .......................................................................................................1 II. JURISDICTION AND VENUE ..........................................................................................5 III. PARTIES .............................................................................................................................7 A. Plaintiff ....................................................................................................................7 -

United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois Eastern Division

Case: 1:18-cv-04534 Document #: 1 Filed: 06/29/18 Page 1 of 130 PageID #:1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION THE KROGER CO.; HY-VEE, INC.; and Case No: ALBERTSONS COMPANIES, INC, Plaintiffs, v. TYSON FOODS, INC.; TYSON CHICKEN, INC.; TYSON BREEDERS, INC.; TYSON POULTRY, INC.; PILGRIM’S PRIDE CORPORATION; KOCH FOODS, INC.; JCG FOODS OF ALABAMA, LLC; JCG FOODS OF GEORGIA, LLC; KOCH MEAT CO., INC.; SANDERSON FARMS, INC.; SANDERSON FARMS, INC. (FOOD DIVISION); SANDERSON FARMS, INC. (PRODUCTION DIVISION); SANDERSON FARMS, INC. (PROCESSING DIVISION); HOUSE OF RAEFORD FARMS, INC.; MAR-JAC POULTRY, INC.; PERDUE FARMS, INC.; PERDUE FOODS, LLC; WAYNE FARMS, LLC; FIELDALE FARMS CORPORATION; GEORGE’S, INC.; GEORGE’S FARMS, INC.; SIMMONS FOODS, INC.; SIMMONS PREPARED FOODS, INC.; O.K. FOODS, INC.; O.K. FARMS, INC.; O.K. INDUSTRIES, INC.; PECO FOODS, INC.; HARRISON POULTRY, INC.; FOSTER FARMS, LLC; FOSTER POULTRY FARMS; CLAXTON POULTRY FARMS, INC.; MOUNTAIRE FARMS, INC.; MOUNTAIRE FARMS, LLC; MOUNTAIRE FARMS OF DELAWARE, INC.; and AGRI STATS, INC., Defendants. COMPLAINT AND DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL Case: 1:18-cv-04534 Document #: 1 Filed: 06/29/18 Page 2 of 130 PageID #:2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. NATURE OF THE ACTION ............................................................................................. 1 A. Defendants Unlawfully Agreed to Curtail the Supply of Chicken ......................... 2 B. Defendants Unlawfully Agreed to Manipulate and Artificially Inflate the Georgia Dock ......................................................................................................... -

The State of the US Livestock and Poultry Economies

Congressional Testimony The State of the U.S. Livestock and Poultry Economies Testimony before Subcommittee on Livestock and Foreign Agriculture Committee on Agriculture United States House of Representatives July 16, 2019 Holly Porter Executive Director Delmarva Poultry Industry, Inc. Good morning and thank you Chairman Costa and Ranking Member Rouzer and members of the subcommittee. I am Holly Porter, the executive director of the Delmarva Poultry Industry, Inc, also known as DPI, the 1,700- member trade association that represents the family farmers, processors and allied businesses within Delaware, the Eastern Shore of Maryland and the Eastern Shore of Virginia, otherwise known as the Delmarva Peninsula. It is a pleasure to be here today representing the meat chicken industry, an industry that started on the Delmarva nearly 100 years ago when Cecil Steele a farmer in Ocean View, Delaware received 500 chicks instead of the 50 that she ordered for eggs. She decided to raise the birds and sell them to a northern market – she made sixty- two cents a pound – which would be $5-$6 today, ordered 1,000 chicks for the next flock and the rest is history. Today on Delmarva our agricultural economy is built on what we refer to as the three-legged stool – the family farmers raising the birds and the grain for feed, and the processors who they both partner with. If any one of those legs were to come off the stool, the economy would collapse. As of 2018, we have more than 1,300 individual family farmers that contract with five companies to handle the poultry health, processing and marketing, also known as the vertically integrated system. -

Findings & Recommendations of the Mountaire Pollution Committee

Findings & Recommendations of the Mountaire Pollution Committee Chris Bason, Executive Director, November 2, 2018 Introduction This report was produced with input from the Center for the Inland Bays Board of Directors’ ad hoc Committee on Mountaire Pollution, formed at its meeting on December 15, 2017. The Committee met twice during January 2018, once during March 2018, once during June 2018, and again in October 2018 to help develop these findings and recommendations. Committee participation included Board Members Vickie York (Board-Elected Director), Jonathan Forte (Board-Elected Director), Rob Robinson (Appointee of the Senate Pro Tem), Scott Andres (Chair of the Scientific & Technical Advisory Committee), Mike Dunmyer (Board Elected Director), and Hans Medlarz (Sussex County); Citizens Advisory Committee Members John Austin and Richard Watson, and CIB staff members Chris Bason (Executive Director) and Michelle Schmidt (Watershed Coordinator). Publicly available information was used to prepare the report, some of which was obtained through Freedom of Information Act requests to government agencies. The Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control (DNREC) was unable to provide much of the information requested due to an ongoing investigation of the violations at the Mountaire facility. The findings section of this report was originally released in April of 2018 during a press event. At that time, the recommendations section was withheld to allow for DNREC to best complete its ongoing investigation into the permit violations at the Mountaire facility. After a consent decree between Mountaire and DNREC was released in June 2018, the Committee met again to request additional information from DNREC. After not receiving the information, the Committee recommended to the Center Board in October to release the recommendations to the public which was done as a press release including this full report. -

Cuppels V. Mountaire Class Action Settlement Administrator RG/2 Claims Administration LLC P.O

EFiled: Mar 22 2021 04:44PM EDT Transaction ID 66444355 Case No. S18C-06-009 CAK IN THE SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF DELAWARE GARY and ANNA-MARIE ) CUPPELS, individually and on ) behalf of all others similarly situated, ) Plaintiffs, ) ) C.A. No.: S18C-06-009 CAK v. ) ) MOUNTAIRE CORPORATION, an ) TRIAL BY JURY OF 12 Arkansas corporation, MOUNTAIRE ) DEMANDED FARMS, INC., a Delaware ) corporation, and ) MOUNTAIRE FARMS OF ) DELAWARE, INC., a Delaware ) corporation. ) Defendants. ) NOTICE OF JOINT MOTION FOR FINAL APPROVAL OF CLASS ACTION SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT AND OTHER RELIEF PLEASE TAKE NOTICE that the attached Joint Motion for Final Approval of Class Action Settlement Agreement and Other Relief will be presented at the Fairness Hearing on April 12, 2021 at 9:30 a.m. BAIRD MANDALAS BROCKSTEDT, LLC /s/ Chase T. Brockstedt Chase T. Brockstedt, Esq. (DE #3815) Stephen A. Spence, Esq. (DE #5392) 1413 Savannah Road, Suite 1 Lewes, Delaware 19958 (302) 645-2262 Attorneys for Gary and Anna-Marie Cuppels and those similarly situated Date: March 22, 2021 EFiled: Mar 22 2021 04:44PM EDT Transaction ID 66444355 Case No. S18C-06-009 CAK IN THE SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF DELAWARE GARY and ANNA-MARIE ) CUPPELS, et al., individually and on ) behalf of all others similarly situated, ) Plaintiffs, ) v. ) ) C.A. No.: S18C-06-009 CAK MOUNTAIRE CORPORATION, an ) Arkansas corporation, MOUNTAIRE ) TRIAL BY JURY OF 12 FARMS, INC., a Delaware ) DEMANDED corporation, and MOUNTAIRE ) FARMS OF DELAWARE, INC., a ) Delaware corporation. ) Defendants. ) JOINT MOTION FOR FINAL APPROVAL OF CLASS ACTION SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT AND OTHER RELIEF Chase T.