Building a Baroque Catholicism.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PARISH INFORMATION on the Cover Wrath and Anger Are Hateful Things, Yet the Sinner PARISH OFFICE HOURS Hugs Them Tight

St. Francis Xavier Parish 24th Sunday in Ordinary Time 13 September 2020 St. Francis Xavier, Acushnet – Diocese of Fall River Mass Schedule From the Pastor’s Desk (September 12th- September 20th) BEATING THE DEVIL AT HIS OWN GAME th Sat. Sept. 12 24 Sunday (Vigil) (Gr) St. John Chrysostom (347-407), a great bishop of the ear- 4:00 pm Pro Populo Sun. Sept. 13 24th Sunday In Ordinary Time (Gr) ly Church, once reflected how Christ won His victory over the devil using the same things that the devil has 7:00am Jean, Helen & Donny Guenette 9:00am For Peace in Our Country used to cause the original sin: 11:00am Month’s Mind Mon. Sept. 14 Exaltation of the Holy Cross (Rd) A virgin, a tree and a death were the symbols of our defeat. The 9:00am Mildred Sorenson virgin was Eve: she had not yet known man; the tree was the tree of Tues. Sept 15 Our Lady of Sorrows (Wh) the knowledge of good and evil; the death was Adam’s penalty. But 9:00am Elaine Correia behold again a Virgin and a tree and a death, those symbols of Wed. Sept 16 Ss. Cornelius & Cyprian (Rd) 9:00am Maria Mendes & Family defeat, become the symbols of his victory. For in place of Eve there is Thurs. Sept 17 St. Robert Bellarmine; Bishop (Wh) Mary; in place of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, the tree 9:00am Manuel Pereira of the Cross; in place of the death of Adam, the death of Christ. -

Church of the Visitation Mantoloking Road, Brick, New Jersey

Church of the Visitation Mantoloking Road, Brick, New Jersey 2 Church of the Visitation 755 Mantoloking Road Brick, N.J. 08723 Welcome! The entire parish community extends a warm welcome to all visitors and new parishioners LITURGY OF THE EUCHARIST Rectory Office Phone: 732-477-0028 Weekend: Saturday 4:00 and 5:30 PM Religious Education: 732-477-5217 Sunday: 6:45, 8:00, 9:30, 11:00 AM, 12:30 PM Daily: Monday-Saturday 7:30 and 8:15 AM (Daily Chapel) Rectory Fax: 732-477-1274 Monday Evenings: 7:30 PM Rectory Address: 730 Lynnwood Ave. Brick, NJ Website Holy Days: See Current Bulletin : www.visitationrcchurch.org Holy Hour: First Fri. of the month 7:00 to 8:00 PM (Church) REV. EDWARD BLANCHETT, PASTOR, EXT. 201 REV. JAMES O’NEILL, PAROCHIAL VICAR, EXT. 220 Baptism Parents or legal guardians are encouraged to register 2 months Assisting Priests in advance to schedule a baptism. Parents and Guardians are Rev. James Sauchelli Rev. Bernard Mohan required and sponsors are encouraged to attend the Baptismal Rev. Msgr. Ricardo Gonzalez Rev. Msgr. Vincent Doyle Formation Session prior to the Baptism. Baptisms are Msgr. Philip Franceschini Rev. Richard Carlson celebrated on Sundays following the 12:30 Mass at 1:45 PM. Deacons Please contact Deacon Sal Vicari at ext. 218 to make Salvatore Vicari, Ext. 218 Nicola Stranieri, Ext. 102 arrangements. Richard Johnston, Ext. 221 Edward Fischer Staff Marriages Denise Patetta, Ext. 201 Nancy Grodberg Ext. 219 The Sacrament of Marriage requires a time of spiritual Parish Secretary/Bulletin Editor Coordinator of Religious preparation. -

Old St. Peter's Protestant Episcopal Church, Philadelphia: an Architectural History and Inventory (1758-1991)

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 1992 Old St. Peter's Protestant Episcopal Church, Philadelphia: An Architectural History and Inventory (1758-1991) Frederick Lee Richards University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Richards, Frederick Lee, "Old St. Peter's Protestant Episcopal Church, Philadelphia: An Architectural History and Inventory (1758-1991)" (1992). Theses (Historic Preservation). 349. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/349 Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Richards, Frederick Lee (1992). Old St. Peter's Protestant Episcopal Church, Philadelphia: An Architectural History and Inventory (1758-1991). (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/349 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Old St. Peter's Protestant Episcopal Church, Philadelphia: An Architectural History and Inventory (1758-1991) Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Richards, Frederick Lee (1992). Old St. Peter's Protestant Episcopal Church, Philadelphia: -

Historic Name Church of the Immaculate Conception & the Michael Ferrall Family Cemetery

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) lilllll"'l:::IIrlhTlI't:lInt of the Interior This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. historic name Church of the Immaculate Conception & the Michael Ferrall Family Cemetery other names/site number __________________________________ street & number 145 South King Street N/rn not for publication city or town ..:;:.;H=a=l=i=f=a=x'---________________________--..:N;..;..J.I lfJ vicinity state North Carolina code ~ county --=H=a==l==i~f::..!::a~x~ _____ code 083 zip code 27839 As the designat8d authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this 0 nomination o request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property !XI meets 0 does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant o nationally 0 statewide 0 locally. -

The Church of the Visitation of the Blessed Virgin Mary May 30, 2021

Serving God’s People The Church of the Visitation since 1892. of the Blessed Virgin Mary 1090 Carmalt Street, Dickson City, PA 18519 Phone: 570-489-2091 ~ Email: [email protected] ~ Website: www.vbvm.org THE VISITATION OF THE BLESSED VIRGIN MARY MAY 31, 2021 MARY SET OUT AND TRAVELED TO THE HILL COUNTRY IN HASTE TO A TOWN OF JUDAH WHERE SHE ENTERED THE HOUSE OF ZECHARIAH AND GREETED ELIZABETH. LUKE 1: 30-40 Pictured left is the stained glass window in the new entrance to the church. The window is based on a mosaic at the Church of the Visitation in Ein Karim, Israel. PARISH STAFF SACRAMENTS Msgr. Patrick J. Pratico, J.C.D., Pastor Reconciliation: Saturday 8:30 a.m., and other times by Karen Wallo, Administrative Assistant request. Robert Manento, Director of Liturgical Music Baptism: Second Sunday of the month at 11:30 a.m. Linda Skierski, Director of Religious Education Registered parishioners may call the parish office to make arrangements. Marriage: Arrangements must be made at least six MASS SCHEDULE months in advance by registered parishioners. Saturday Vigil: 4:00 p.m., Sunday: 8:00 &10:30 a.m. Monthly Visitation of the Sick/Homebound: Call the parish office to be placed on the list. Weekdays: 7:30 a.m. Holy Days: (Vigil 4:00 p.m.), 7:30 a.m., & 5:30 p.m. Care of the Sick: Please notify us at any time of the (Please check inside bulletin to confirm Mass times) seriously ill, hospitalized or those needing anointing. We, the parish community of The Visitation of the Blessed Virgin Mary, in union with the guidance of the Holy Spirit and the leadership of our bishop and our pastor are called through Baptism to live the gospel of Jesus Christ. -

Redalyc.Saint Francis Xavier and the Shimazu Family

Bulletin of Portuguese - Japanese Studies ISSN: 0874-8438 [email protected] Universidade Nova de Lisboa Portugal López-Gay, Jesús Saint Francis Xavier and the Shimazu family Bulletin of Portuguese - Japanese Studies, núm. 6, june, 2003, pp. 93-106 Universidade Nova de Lisboa Lisboa, Portugal Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=36100605 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative BPJS, 2003, 6, 93-106 SAINT FRANCIS XAVIER AND THE SHIMAZU FAMILY Jesús López-Gay, S.J. Gregorian Pontifical University, Rome Introduction Exactly 450 years ago, more precisely on the 15th of August 1549, Xavier set foot on the coast of Southern Japan, arriving at the city of Kagoshima situated in the kingdom of Satsuma. At that point in time Japan was politically divided. National unity under an Emperor did not exist. The great families of the daimyos, or “feudal lords” held sway in the main regions. The Shimazu family dominated the region of Kyúshú, the large island in Southern Japan where Xavier disembarked. Xavier was accompa- nied by Anjiró, a Japanese native of this region whom he had met in Malacca in 1547. Once a fervent Buddhist, Anjiró was now a Christian, and had accompanied Xavier to Goa where he was baptised and took the name Paulo de Santa Fé. Anjiró’s family, his friends etc. helped Xavier and the two missionaries who accompanied him (Father Cosme de Torres and Brother Juan Fernández) to instantly feel at home in the city of Kagoshima. -

The Miracles of St. Francis Xavier in San Francisco Javier, El Sol En Oriente, a Jesuit Comedy

THE MIRACLES OF ST. FRANCIS XAVIER IN SAN FRANCISCO JAVIER, EL SOL EN ORIENTE, A JESUIT COMEDY Sabyasachi Mishra GRISO-Universidad de Navarra Saints across the world are revered by the people for their selfless service towards humanity. In the Catholic tradition of sainthood, the name of St. Francis Xavier is taken with great respect. In many parts of the world, he is not only revered by the Christians, but people from the other faith also give him love and much respect. At a time, when travelling to another countries was considered as a difficult task, St. Francis Xavier travelled and preached Christianity in the lesser known parts of the world. Born on 7 April 1506 in a noble family of Navarra, he saw the loss of the independence of the contemporary Navarre state. When he was nineteen years old, he was sent to Paris for higher studies in Colegio de Santa Barbara and there he come in contact with St. Ignatius de Loyola. Later on, they became good friends and in a discussion when Father Ignatius told him that what is the use of wining the whole world if someone lose his soul? These words made him think much and he left showing his opulence. Later on, the blessed saint dedicated much of his time in studies and in 1534 he confessed and received communion with some of his friends. Initially he had plans to go to Jerusalem, but due to the ongoing war between Venetians and Turks, they had no op- tion rather to end this plan. After meeting with father Ignatius, he decided to stay in Italy and to spread the message of Christianity with zeal in universities. -

A Guide to the History, Art and Architecture of the Church of St. Lawrence, Asheville, North Carolina

Cfje Liorarp o£ ttje {Hnttiersitp of Jl3ort|) Carolina Collection of iRoctf; Carolinians ignfioturB bg Sofin feprunt ^ill of tJ)e Class of 1889 Co 282.09 This BOOK may be V JBfi g>tHatorence Catftoltc €fmrcf) * SsfjebiUe, Uortf) Carolina 1923 BelwuiU Abbty LIBRARY Ekluuanl, N. C. 9 #uttie tOti)E Jlistorp, Art anb Architecture of Cfje Cfjurcf) of %>l Hatorence gtenebtUe, J^ortf) Carolina - Belmont Abbey vBelmonV- N^-€t~ Prepareb fap tfjc labtesf of tf)e <ar H>ocietp VJitl) tfic approbal of tljc -pastor Bet). Horns fosiepi) Pour, Jffl.g., $f).1L Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from :e of Museum and Library Services, under the provisions of the Library Services and Technology Act, administered by the State Library of North Carolina. Grant issued to subcontractor UNC-CH for Duke University's Religion in North Carolina project. http://archive.org/details/guidetohistoryaruOchur ktlmont Abbe3r -Belmont, N. C . THE RT. REV. LEO HAID.O.S.B.. BISHOP OF NORTH CAROLINA Jtagtora JAMES CARDINAL GIBBONS First Bishop of North Carolina. Purchased the first Catholic Church property in Asheville, N. C, 1868. THE REV. DR. JEREMIAH P. O'CONNELL THE VERY REV. LAWRENCE P. O'CONNELL, V.G. Traveling Missioners of the Carolinas who built the first Catholic Church in Asheville in 1869. RT. REV. JOHN BARRY, D.D. The first Catholic Priest to minister in Asheville—about the year 1840. THE REV. JOHN B. WHITE The first resident Priest in Asheville. RT. REV. MSGR. PETER G. MARION, Pastor Rev. Francis J. Gallagher, Curate RT. REV. MSGR. PATRICK F. -

To Center City: the Evolution of the Neighborhood of the Historicalsociety of Pennsylvania

From "Frontier"to Center City: The Evolution of the Neighborhood of the HistoricalSociety of Pennsylvania THE HISToRICAL SOcIETY OF PENNSYLVANIA found its permanent home at 13th and Locust Streets in Philadelphia nearly 120 years ago. Prior to that time it had found temporary asylum in neighborhoods to the east, most in close proximity to the homes of its members, near landmarks such as the Old State House, and often within the bosom of such venerable organizations as the American Philosophical Society and the Athenaeum of Philadelphia. As its collections grew, however, HSP sought ever larger quarters and, inevitably, moved westward.' Its last temporary home was the so-called Picture House on the grounds of the Pennsylvania Hospital in the 800 block of Spruce Street. Constructed in 1816-17 to exhibit Benjamin West's large painting, Christ Healing the Sick, the building was leased to the Society for ten years. The Society needed not only to renovate the building for its own purposes but was required by a city ordinance to modify the existing structure to permit the widening of the street. Research by Jeffrey A. Cohen concludes that the Picture House's Gothic facade was the work of Philadelphia carpenter Samuel Webb. Its pointed windows and crenellations might have seemed appropriate to the Gothic darkness of the West painting, but West himself characterized the building as a "misapplication of Gothic Architecture to a Place where the Refinement of Science is to be inculcated, and which, in my humble opinion ought to have been founded on those dear and self-evident Principles adopted by the Greeks." Though West went so far as to make plans for 'The early history of the Historical Soiety of Pennsylvania is summarized in J.Thomas Scharf and Thompson Westcott, Hisiory ofPhiladelphia; 1609-1884 (2vols., Philadelphia, 1884), 2:1219-22. -

527-37 W GIRARD AVE Name of Resource: North Sixth Street

ADDRESS: 527-37 W GIRARD AVE Name of Resource: North Sixth Street Farmers Market House and Hall Proposed Action: Designation Property Owner: Franklin Berger Nominator: Oscar Beisert, Keeping Society of Philadelphia Staff Contact: Laura DiPasquale, [email protected], 215-686-7660 OVERVIEW: This nomination proposes to designate the property at 527-37 W Girard Avenue as historic and list it on the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places. The nomination contends that the former North Sixth Street Farmers’ Market House and Hall, which is composed of several interconnecting masses constructed between 1886 and 1887, is significant under Criteria for Designation A, E, and J. Under Criterion A, the nomination argues that the property represents the development of Philadelphia in the second half of the nineteenth century as the city transitioned from the use of outdoor, public food markets to privately-owned, multi-purpose, indoor markets and halls. Under Criterion J, the nomination asserts that the mixed-use building played an important role in the cultural, social, and economic lives of the local and predominantly German- American community. The nomination also argues that the building is significant as the work of architects Hazelhurt & Huckel, satisfying Criterion E. The nomination places the period of significance between the date of construction in 1886 and 1908, the year it ceased operations as a farmers’ market, but notes that the community significance may extend through the 1940s, until which time the building remained in use as a public hall and movie theater. STAFF RECOMMENDATION: The staff recommends that the nomination demonstrates that the property at 527-37 W Girard Avenue satisfies Criteria for Designation A, E, and J. -

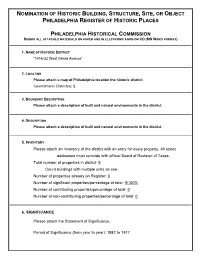

Nomination of Historic Building, Structure, Site, Or Object Philadelphia Register of Historic Places

NOMINATION OF HISTORIC BUILDING, STRUCTURE, SITE, OR OBJECT PHILADELPHIA REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES PHILADELPHIA HISTORICAL COMMISSION SUBMIT ALL ATTACHED MATERIALS ON PAPER AND IN ELECTRONIC FORM ON CD (MS WORD FORMAT) 1. NAME OF HISTORIC DISTRICT “1416-32 West Girard Avenue” 2. LOCATION Please attach a map of Philadelphia location the historic district. Councilmanic District(s): 5 3. BOUNDARY DESCRIPTION Please attach a description of built and natural environments in the district. 4. DESCRIPTION Please attach a description of built and natural environments in the district. 5. INVENTORY Please attach an inventory of the district with an entry for every property. All street addresses must coincide with official Board of Revision of Taxes. Total number of properties in district: 9 Count buildings with multiple units as one. Number of properties already on Register: 0 Number of significant properties/percentage of total: 9/100% Number of contributing properties/percentage of total: 0 Number of non-contributing properties/percentage of total: 0 6. SIGNIFICANCE Please attach the Statement of Significance. Period of Significance (from year to year): 1882 to 1917 CRITERIA FOR DESIGNATION: The historic resource satisfies the following criteria for designation (check all that apply): (a) Has significant character, interest or value as part of the development, heritage or cultural characteristics of the City, Commonwealth or Nation or is associated with the life of a person significant in the past; or, (b) Is associated with an event of importance -

ST. MARY's PARISH 8 CHURCH ST. HOLLISTON, MA 01746 Paid CHRISTMAS MASSES COOKIE WALK RAISES $2,220 for the POOR OF

Non-profit ST. MARY’S PARISH Organization 8 CHURCH ST. u.s. postage HOLLISTON, MA 01746 paid Holliston, MA 01746 Permit no. 2 CHRISTMAS MASSES TUESDAY , DECEMBER 24, CHRISTMAS EVE 4 PM Masses in both the Church and Father Haley Hall (Hall Mass includes the Christmas Pageant, 4 PM parking is difficult, so please plan accordingly) 5:30 PM Mass in the Church 7:30 PM Mass in the Church 11:00 PM (Midnight) Mass in the Church WED NESDAY, DECEMBER 25, CHRISTMAS DAY 9:30 AM Mass in the Church 11:30 AM Mass in the Church COOKIE WALK RAISES $2,220 FOR THE POOR OF HAITI! Tables groaned under the weight of nearly 3,000 homemade Christmas cookies. They were baked by our Middle School Youth Group teens and sold at the December 7/8 Cookie Walk after all Masses. The funds raised are sent to support the poor of Haiti through Mother Theresa’s Missionaries of Charity there. Thank you to all who took part in this delicious and meaningful annual event! St. Mary’s Parish Newsletter January, 2020 ~ Volume 45, Number 5 St. Mary’s Parish 8 Church Street Holliston, MA 01746 Rectory: 429-4427, 879-2322 Religious Education Center: 429-6076 Fax: 429-3324 ~ Music: 429-4427 Religious Education Email: [email protected] Parish Email Address: [email protected] Website: www.stmarysholliston.com Mission ~ “To Know Christ and to make Him Known.” Parish Clergy Rev. Mark J. Coiro, Pastor The Xaverian Fathers, Weekend Assistance Rev. James Flynn, Weekend Assistance Deacon John Barry, Permanent Deacon Deacon Martin Breinlinger, Senior Deacon 1870 to 2020.