Chapter 22: Literature: Novels, Plays, Essays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ina Coolbrith of California's "Overland Trinity95 by BENJAMIN DE CASSERES

Boolcs and the Book World of The Sun, December 7, 1919. 15 Ina Coolbrith of California's "Overland Trinity95 By BENJAMIN DE CASSERES. written, you know. I have just sent down ASTWARD the star of literary cm-- town for one of my books, want 'A J and I pire takes its way. After twenty-liv-e to paste a photograph as well as auto- years Ina Donna Coolbrith, crowned graph in it to mail to you. poet laureate of California by the Panama-P- "The old Oakland literary days! Do acific Exposition, has returned to yon know you were the first. one who ever New York. Her house on Russian Hill, complimented me on my choice of reading San Francisco, the aristocratic Olympus matter? Nobody at home bothered then-hea- of the Musaj of the Pacific slope, stands over what I read. I was an eager, empty. thirsty, hungry little kid and one day It is as though California had closed a k'Prsmmm mm m:mmm at the library I drew out a volume on golden page of literary and artistic mem- Pizzaro in Pern (I was ten years old). ories in her great epic for the life of You got the book and stamped it for me; Miss Coolbrith 'almost spans the life of and as you handed it to me you praised California itself. Her active and acuto me for reading books of that nature. , brain is a storehouse of memories and "Proud ! If you only knew how proud ' anecdote of those who have immortalized your words made me! For I thought a her State in literature Bret Harte, Joa- great deal of you. -

American Studies

american studies an interdisciplinary journal sponsored by the Midcontinent American Studies Association, the University of Kansas and the University of Missouri at Kansas City stuart levine, editor editorial board edward f. grief, English, University of Kansas, Chairman norm an r. yetman, American Studies, University of Kansas, Associate Editor William C Jones, College of Arts & Sciences, University of Missouri at Kansas City, Consulting Editor John braeman, History, University of Nebraska (1976) hamilton cravens. History, Iowa State University (1976) charles C. eldredge. History of Art, University of Kansas (1977) jimmie I. franklin. History, Eastern Illinois University (1977) robert a. Jones, Sociology, University of Illinois (1978) linda k. kerber, History, University of Iowa (1978) roy r. male, English, University of Oklahoma (1975) max j. skidmore, Political Science, Southwest Missouri State University (1975) officers of the masa president: Jules Zanger, English, Southern Illinois University at Edwardsville vice-president: Hamilton Cravens, History, Iowa State University executive secretary: Norman H. Hostetler, American Studies, University of Nebraska editor: Stuart Levine, American Studies, University of Kansas copy editor and business manager: William A. Dobak editorial assistants: N. Donald Cecil, Carol Loretz Copyright, Midcontinent American Studies Association, 1974. Address business correspondence to the Business Manager and all editorial correspondence to the Editor. ON THE COVER: Top left, Selig Silvers tein's membership card in Anarchist Federation of America; top right, twenty seconds after bomb explosion in Union Square, New York City, March 28, 1908, Silverstein the bomb-thrower lies mortally wounded and a bystander lies dead; bottom, police at whom Silverstein attempted to throw bomb. See pages 55-78. -

Three Library Speakers Series

THREE LIBRARY SPEAKERS SERIES ARDEN-DIMICK LIBRARY SPEAKERS SERIES OFF CAMPUS, DROP-IN, NO REGISTRATION REQUIRED All programs are on Mondays, 10:00 a.m. to 11:30 a.m. Because the location is a public library, the meetings are open to the public. 891 Watt Avenue, Sacramento 95864 NOTE: Community Room doors on north side open at 9:45 a.m. Leader: Carolyn Martin, [email protected] March 9 How Women Finally Got the Right to Vote – Carolyn Martin The frequently frustrating suffrage struggle celebrated the California victory in 1911. It was an innovative and invigorating campaign. Learn about our State’s leadership, the movement’s background and ultimately national victory in 1920. March 16 Sacramento’s Hidden Art Deco Treasures – Bruce Marwick The Preservation Chair of the Sacramento Art Deco Society will share images of buildings, paintings and sculptures that typify the beautiful art deco period. Sacramento boasts a high concentration of WPA (Works Progress Administration) 1930s projects. His special interest, murals by artists Maynard Dixon, Ralph Stackpole and Millard Sheets will be featured. March 23 Origins of Western Universities – Ed Sherman Along with libraries and museums, our universities act as memory for Western Civilization. How did this happen? March 30 The Politics of Food and Drink – Steve and Susie Swatt Historic watering holes and restaurants played important roles in the temperance movement, suffrage, and the outrageous shenanigans of characters such as Art Samish, the powerful lobbyist for the alcoholic beverage industry. New regulations have changed both the drinking scene and Capitol politics. April 6 Communication Technology and Cultural Change - Phil Lane Searching for better communication has evolved from written language to current technological developments. -

Mining Kit Teacher Manual Contents

Mining Kit Teacher Manual Contents Exploring the Kit: Description and Instructions for Use……………………...page 2 A Brief History of Mining in Colorado ………………………………………page 3 Artifact Photos and Descriptions……………………………………………..page 5 Did You Know That…? Information Cards ………………………………..page 10 Ready, Set, Go! Activity Cards ……………………………………………..page 12 Flash! Photograph Packet…………………………………………………...page 17 Eureka! Instructions and Supplies for Board Game………………………...page 18 Stories and Songs: Colorado’s Mining Frontier ………………………………page 24 Additional Resources…………………………………………………………page 35 Exploring the Kit Help your students explore the artifacts, information, and activities packed inside this kit, and together you will dig into some very exciting history! This kit is for students of all ages, but it is designed to be of most interest to kids from fourth through eighth grades, the years that Colorado history is most often taught. Younger children may require more help and guidance with some of the components of the kit, but there is something here for everyone. Case Components 1. Teacher’s Manual - This guidebook contains information about each part of the kit. You will also find supplemental materials, including an overview of Colorado’s mining history, a list of the songs and stories on the cassette tape, a photograph and thorough description of all the artifacts, board game instructions, and bibliographies for teachers and students. 2. Artifacts – You will discover a set of intriguing artifacts related to Colorado mining inside the kit. 3. Information Cards – The information cards in the packet, Did You Know That…? are written to spark the varied interests of students. They cover a broad range of topics, from everyday life in mining towns, to the environment, to the impact of mining on the Ute Indians, and more. -

Gold Fever! Seattle Outfits the Klondike Gold Rush. Teaching with Historic Places

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 442 682 SO 031 322 AUTHOR Blackburn, Marc K. TITLE Gold Fever! Seattle Outfits the Klondike Gold Rush. Teaching with Historic Places. INSTITUTION National Register of Historic Places, Washington, DC. Interagency Resources Div. PUB DATE 1999-00-00 NOTE 28p. AVAILABLE FROM Teaching with Historic Places, National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service, 1849 C Street, NW, Suite NC400, Washington, DC 20240. For full text: http://www.cr.nps.gov/nr/twhp/wwwlps/lessons/55klondike/55 Klondike.htm PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Foreign Countries; Historic Sites; *Local History; Primary Sources; Secondary Education; Social Studies; *United States History; *Urban Areas; *Urban Culture IDENTIFIERS Canada; *Klondike Gold Rush; National Register of Historic Places; *Washington (Seattle); Westward Movement (United States) ABSTRACT This lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places registration file, "Pioneer Square Historic District," and other sources about Seattle (Washington) and the Klondike Gold Rush. The lesson helps students understand how Seattle exemplified the prosperity of the Klondike Gold Rush after 1897 when news of a gold strike in Canada's Yukon Valley reached Seattle and the city's face was changed dramatically by furious commercial activity. The lesson can be used in units on western expansion, late 19th-century commerce, and urban history. It is divided into the following sections: "About This Lesson"; "Setting the Stage: Historical -

ESTELLE PARSONS & NAOMI LIEBLER Monday, April 13

SAVORING THE CLASSICAL TRADITION IN DRAMA ENGAGING PRESENTATIONS BY THE SHAKESPEARE GUILD IN COLLABORATION WITH THE NATIONAL ARTS CLUB THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING UNION THE LAMBS, NEW YORK CITY ESTELLE PARSONS & NAOMI LIEBLER Monday, April 13 For this special gathering, the GUILD is delighted to join forces with THE LAMBS, a venerable theatrical society whose early leaders founded Actors’ Equity, ASCAP, and the Screen Actors Guild. Hal Holbrook offered Mark Twain Tonight to his fellow Lambs before taking the show public. So it’s hard to imagine a better THE LAMBS setting for ESTELLE PARSONS and NAOMI LIEBLER to present 3 West 51st Street a dramatic exploration of “Shakespeare’s Old Ladies.” A Manhattan member of the American Theatre Hall of Fame and a PROGRAM 7:00 P.M. former head of The Actors Studio, Ms. Parsons has been Members $5 nominated for five Tony Awards and earned an Oscar Non-Members $10 as Blanche Barrow in Bonnie and Clyde (1967). Dr. Liebler, a professor at Montclair State, has given us such critically esteemed studies as Shakespeare’s Festive Tragedy. Following their dialogue, a hit in 2011 at the New York Public Library, they’ll engage in a wide-ranging conversation about its key themes. TERRY ALFORD Tuesday, April 14 To mark the 150th anniversary of what has been called the most dramatic moment in American history, we’re pleased to host a program with TERRY ALFORD. A prominent Civil War historian, he’ll introduce his long-awaited biography of an actor who NATIONAL ARTS CLUB co-starred with his two brothers in a November 1864 15 Gramercy Park South benefit of Julius Caesar, and who restaged a “lofty Manhattan scene” from that tragedy five months later when he PROGRAM 6:00 P.M. -

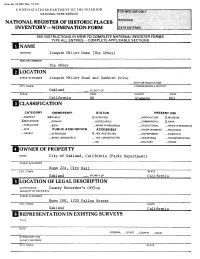

Hclassification

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OE THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS [NAME HISTORIC Joaquin Miller Home (The Abbey) AND/OR COMMON The Abbey LOCATION STREETS.NUMBER Joaquin Miller Road and Sanborn Drive _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Oakland _.. VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE California 06 AT ameda 001 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT XXPUBLIC X-OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE X_MUSEUM J^BUILDINGIS) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL X_PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME City of Oakland, California (Parks Department) STREET & NUMBER Room 224, City Hall CITY, TOWN STATE Oakland VICINITY OF California COURTHOUSE, County Recorder ! s Office REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. STREET & NUMBER Room 100^ 1225 Fallen Street CITY. TOWN STATE Oakland California REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE DATE .FEDERAL _STATE __COUNTY _LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY, TOWN DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT -DETERIORATED —UNALTERED XXORIGINALSITE _MOVED DATE. X-GOOD _RUINS X_ALTERED _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Joaquin Miller House is a small three-part frame building at the foot of the steep hills East of Oakland California. Composed of three single rooms joined together, the so-called "Abbey" must be seen as the most provincial of efforts to impose gothic-revival detail upon the three rooms. -

71St Cover F

SEVENTY-FIRST STREET 71VOLUME 12 ● NUMBER 2 MMC Gallery Named Hewitt Gallery of Art TABLE OF CONTENTS MMC Gallery Named Hewitt Gallery of Art In honor of Marsha A. Hewitt ’67 and husband Carl’s generous donation SEVENTY-FIRST STREET to the College, the MMC Gallery of Art has a new name. Turn the page to learn more about this couple’s deep commitment to MMC . 2 Grant Funds One MMC Student’s Passion for Science VOLUME 12 ● NUMBER 2 Elizabeth Perez ’06 had a unique opportunity to work full-time FALL 2004 on her research in molecular neuroscience this summer 71 thanks to a grant from Bristol-Myers Squibb . 4 Editor: Erin J. Sauer Design: Connelly Design Fundraising Recap . 6 The Tamburro Family’s Legacy 71st Street is published twice a Impact of Annual Fund Donations year by the Office of Institutional Advancement at Marymount Greek Student Attends MMC Thanks to Niarchos Foundation Manhattan College. The title SAT Scores of MMC Freshman on the Rise recognizes the many alumni and faculty who have come to refer Spring Round-Up affectionately to the college The events and happenings that shaped our spring . 8 by its Upper East Side address. Campus Notes Marymount Manhattan College 221 East 71st Street Faculty announcements, notable lectures, theatre events, award winners, New York, NY 10021 and other interesting news from around campus . 14 (212) 517-0450 Class Notes Find out what your fellow alumni are up to . 18 The views and opinions expressed by those in this magazine are Alumni Calendar . 24 independent and do not necessarily represent those of Marymount Manhattan College. -

Gold Rush Student Activity Gold Rush Jobs

Gold Rush Student Activity Gold Rush Jobs Not everyone was a miner during the California Gold Rush. The discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in 1848 prompted the migration of approximately 300,000 people to California during the Gold Rush. While many were hopeful miners, some of Placer County’s most well-known pioneers created businesses to sell products or provide services to miners. Mining was difficult and dangerous, and not always profitable. Other professions could promise more money, and they helped create Placer County as we know it today. Learn about these professions below. Barbershop: Not all professions required hard manual labor. Barbers and bathhouses were popular amongst miners, who came to town for supplies, business, entertainment, and a good bath. Richard Rapier was born free in the slave state of Alabama in 1831. He attended school before moving to California in 1849. He mined and farmed before he purchased a building on East Street and opened a barbershop. He built up a loyal clientele and expanded to include a bath- house. Blacksmith: Blacksmiths were essential to the Gold Rush. Their ability to shape and repair metal goods pro- vided a steady stream of work. Blacksmiths repaired mining tools, mended wagons, and made other goods. Moses Prudhomme was a Canadian who came around Cape Horn to California in 1857. He tried mining but returned to his previous trade – blacksmithing. He had a blacksmith shop in Auburn. Placer County Museums, 101 Maple Street Room 104, Auburn, CA 95603 [email protected] — (530) 889-6500 Farming: Placer County’s temperate climate is Bernhard Bernhard was a German immigrant who good for growing a variety of produce. -

The American Side of the Line: Eagle City's Origins As an Alaska Gold Rush Town As

THE AMERICAN SIDE OF THE LINE Eagle City’s Origins as an Alaskan Gold Rush Town As Seen in Newspapers and Letters, 1897-1899 National Park Service Edited and Notes by Chris Allan THE AMERICAN SIDE OF THE LINE Eagle City’s Origins as an Alaskan Gold Rush Town National Park Service Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve 2019 Acknowledgments I want to thank the staff of the Alaska State Library’s Historical Collections, the University of Alaska Fairbanks’s Alaska and Polar Regions Collections & Archives, the University of Washington’s Special Collections, and the Eagle Historical Society for caring for and making available the photographs in this volume. For additional copies contact: Chris Allan National Park Service 4175 Geist Road Fairbanks, Alaska 99709 Printed in Fairbanks, Alaska February 2019 Front Cover: Buildings in Eagle’s historic district, 2007. The cabin (left) dates from the late 1890s and features squared-off logs and a corrugated metal roof. The red building with clapboard siding was originally part of Ft. Egbert and was moved to its present location after the fort was decommissioned in 1911. Both buildings are owned by Dr. Arthur S. Hansen of Fairbanks. Photograph by Chris Allan, used with permission. Title Page Inset: Map of Alaska and Canada from 1897 with annotations in red from 1898 showing gold-rich areas. Note that Dawson City is shown on the wrong side of the international boundary and Eagle City does not appear because it does not yet exist. Courtesy of Library of Congress (G4371.H2 1897). Back Cover: Miners at Eagle City gather to watch a steamboat being unloaded, 1899. -

(Oncorhynchus Mykiss) in Streams of the San Francisco Estuary, California

Historical Distribution and Current Status of Steelhead/Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in Streams of the San Francisco Estuary, California Robert A. Leidy, Environmental Protection Agency, San Francisco, CA Gordon S. Becker, Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration, Oakland, CA Brett N. Harvey, John Muir Institute of the Environment, University of California, Davis, CA This report should be cited as: Leidy, R.A., G.S. Becker, B.N. Harvey. 2005. Historical distribution and current status of steelhead/rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in streams of the San Francisco Estuary, California. Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration, Oakland, CA. Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration TABLE OF CONTENTS Forward p. 3 Introduction p. 5 Methods p. 7 Determining Historical Distribution and Current Status; Information Presented in the Report; Table Headings and Terms Defined; Mapping Methods Contra Costa County p. 13 Marsh Creek Watershed; Mt. Diablo Creek Watershed; Walnut Creek Watershed; Rodeo Creek Watershed; Refugio Creek Watershed; Pinole Creek Watershed; Garrity Creek Watershed; San Pablo Creek Watershed; Wildcat Creek Watershed; Cerrito Creek Watershed Contra Costa County Maps: Historical Status, Current Status p. 39 Alameda County p. 45 Codornices Creek Watershed; Strawberry Creek Watershed; Temescal Creek Watershed; Glen Echo Creek Watershed; Sausal Creek Watershed; Peralta Creek Watershed; Lion Creek Watershed; Arroyo Viejo Watershed; San Leandro Creek Watershed; San Lorenzo Creek Watershed; Alameda Creek Watershed; Laguna Creek (Arroyo de la Laguna) Watershed Alameda County Maps: Historical Status, Current Status p. 91 Santa Clara County p. 97 Coyote Creek Watershed; Guadalupe River Watershed; San Tomas Aquino Creek/Saratoga Creek Watershed; Calabazas Creek Watershed; Stevens Creek Watershed; Permanente Creek Watershed; Adobe Creek Watershed; Matadero Creek/Barron Creek Watershed Santa Clara County Maps: Historical Status, Current Status p. -

Public Opinion and News Reporting: Different Viewpoints, Changing Perspectives

Public Opinion and News Reporting: Different Viewpoints, Changing Perspectives Grades: 7-HS Subjects: History, Oregon History, Civics, Social Studies Suggested Time Allotment: 1-2 class periods Lesson Background: Our impressions of events can often be influenced by the manner in which they are reported to us in the media. Begin by staging a class discussion of some recent news event(s) that have caused controversy. Can the students think of any news stories that strongly divide public opinions? Any that have been reported in a variety of different ways, depending on which television channels you watch or magazines you read? Can they think of examples where they thought one way or formed a certain opinion about a certain news event, only to have their minds change and opinion shift later, when more information came to light in the media? Moving on from this discussion, the lesson can demonstrate these issues of perspective. Lesson #1: Joaquin Miller—Genius or Cad? Joaquin Miller was the pen name of Cincinnatus Heine Miller, a colorful and controversial poet of the nineteenth century. (Read a detailed biography of Joaquin Miller on Wikipedia, here.) Known in his day as the ‘Poet of the Sierras,’ the ‘Byron of the Rockies,’ and the ‘Bard of Oregon,’ Miller became a celebrity throughout the United States, and especially in England. He was an associate of such enduring literary figures as Ambrose Bierce and Brett Hart. However, it could be argued that Miller’s fame came more from the popular image he created for himself—frontiersman, outdoorsman—than from the actual quality of his literary work.