ENGL 4384: Senior Seminar Student Anthology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protecting Wildlife for the Future

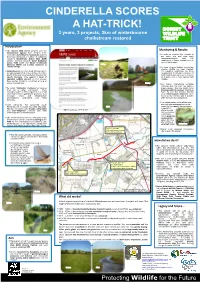

CINDERELLA SCORES A HAT-TRICK! 3 years, 3 projects, 3km of winterbourne chalkstream restored Introduction The Dorset Wild Rivers project and the Monitoring & Results Environment Agency have created three successful winterbourne restoration projects In order to measure the impacts of that have delivered a number of outcomes our work, pre and post work including Biodiversity Action Plan (BAP) macroinvertebrate and fish targets, working towards Good Ecological monitoring is being carried out as Status (GES under the Water Framework part of the project. Directive (WFD) and building resilience to climate change. A more diverse habitat supporting diverse wildlife has been created. Winterbournes are rare chalk streams which The bankside vegetation has been are groundwater fed and only flow at certain manipulated to provide a mixture of times of the year as groundwater levels in the both shaded and more open sections aquifer fluctuate. They support a range of of channel and a more species rich specialist wildlife adapted to this unusual margin. flow regime, including a number of rare or scarce invertebrates. Our macro invertebrate sampling indicates that the work has been a So called “Cinderella” chalkstreams because great success: the rare mayfly larva they are so often overlooked. Their Paraleptophlebia werneri (Red Data ecological value is often degraded as a result Book 3), and the notable blackfly of pressures from agricultural practices, land larva Metacnephia amphora, were drainage, urban and infrastructure found in the stream only 6 months development, abstraction and flood after the work was completed. defences. The Conservation value of the new Over centuries, the spring-fed South channel was reassessed using the Winterbourne in Dorset has been degraded. -

Gus Van Sant Regis Dialogue Formatted

Gus Van Sant Regis Dialogue with Scott Macaulay, 2003 Scott Macaulay: We're here at the Walker Art Center for Regis dialogue with American filmmaker Gus Van Sant. He'll be discussing the unique artistic vision that runs through his entire body of work. Gus was first recognized for a trilogy of films that dealt with street hustlers, Mala Noche, Drugstore Cowboy, My Own Private Idaho. He then went on to experiment with forum and a number of other films including To Die For, Psycho and even Cowgirls Get the Blues. Gus is perhaps best known for his films, Goodwill Hunting and Finding Forrester, but all of his work including his latest film, Gerry, has his own unique touch. We'll be discussing Gus' films today during this Regis dialogue. I'm Scott Macaulay, producer and editor of Filmmaker Magazine. I'll be your guide through Gus' work today in this Regis dialogue. Thanks. Gus Van Sant: Thank you. Scott Macaulay: It's a real pleasure to be here with Gus Van Sant on this retrospective ... Which is called on the road again. I guess there are a lot of different illusions in that title, a lot of very obvious ones because a lot of Gus' movies deal with travel and change and people going different places, both locations within America but also in their lives. But another interesting implication of the title is that this retrospective is occurring on the eve of the release here and also nationwide of Gerry, which is really one of Gus' best and most moving films but it's also yet sort of another new direction for Gus as a filmmaker. -

Another Look at the Cultural Politics of My Own Private Idaho

Journal X Volume 7 Number 1 Autumn 2002 Article 3 2020 Toward a Postmodern Pastoral: Another Look at the Cultural Politics of My Own Private Idaho Sharon O'Dair University of Alabama Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/jx Part of the American Film Studies Commons Recommended Citation O'Dair, Sharon (2020) "Toward a Postmodern Pastoral: Another Look at the Cultural Politics of My Own Private Idaho," Journal X: Vol. 7 : No. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/jx/vol7/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal X by an authorized editor of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. O'Dair: Toward a Postmodern Pastoral: Another Look at the Cultural Politi Toward a Postmodern Pastoral: Another Look at the Cultural Politics of My Own Private Idaho Sharon O'Dair Sharon O'Dair is Gus Van Sant's My Own Private Idaho (1991) is a professor of English film that rewrites Shakespeare's Henriad1 by fol at the University of lowing the adventures in the Pacific Northwest Alabama, where she of two male prostitutes, Scott Favor (played by teaches in the Hub- Keanu Reeves) and Mike Waters (played by son Strode Program in Renaissanc Stud River Phoenix). The film is a spicy conceit, but ies. She is the author in the criticism produced so far on it, cultural of Class, Critics, critique is bland and predictable, a register less and Shakespeare: of the film's politics than the critics'. -

The Natural Capital of Temporary Rivers: Characterising the Value of Dynamic Aquatic–Terrestrial Habitats

VNP12 The Natural Capital of Temporary Rivers: Characterising the value of dynamic aquatic–terrestrial habitats. Valuing Nature | Natural Capital Synthesis Report Lead author: Rachel Stubbington Contributing authors: Judy England, Mike Acreman, Paul J. Wood, Chris Westwood, Phil Boon, Chris Mainstone, Craig Macadam, Adam Bates, Andy House, Dídac Jorda-Capdevila http://valuing-nature.net/TemporaryRiverNC Suggested citation: Stubbington, R., England, J., Acreman, M., Wood, P.J., Westwood, C., Boon, P., The Natural Capital of Mainstone, C., Macadam, C., Bates, A., House, A, Didac, J. (2018) The Natural Capital of Temporary Temporary Rivers: Rivers: Characterising the value of dynamic aquatic- terrestrial habitats. Valuing Nature Natural Capital Characterising the value of dynamic Synthesis Report VNP12. The text is available under the Creative Commons aquatic–terrestrial habitats. Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-SA 4.0) Valuing Nature | Natural Capital Synthesis Report Contents Introduction: Services provided by wet and the natural capital of temporary rivers.............. 4 dry-phase assets in temporary rivers................33 What are temporary rivers?...................................... 4 The evidence that temporary rivers deliver … services during dry phases...................34 Temporary rivers in the UK..................................... 4 Provisioning services...................................34 The natural capital approach Regulating services.......................................35 to ecosystem protection............................................ -

The Nelson Ranch Located Along the Shasta River Has Two Flow Gaging

Baseline Assessment of Salmonid Habitat and Aquatic Ecology of the Nelson Ranch, Shasta River, California Water Year 2007 Jeffrey Mount, Peter Moyle, and Michael Deas, Principal Investigators Report prepared by: Carson Jeffres (Project lead), Evan Buckland, Bruce Hammock, Joseph Kiernan, Aaron King, Nickilou Krigbaum, Andrew Nichols, Sarah Null Report prepared for: United States Bureau of Reclamation Klamath Area Office Center for Watershed Sciences University of California, Davis • One Shields Avenue • Davis, CA 95616-8527 Table of Contents 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..................................................................................................................................2 2. INTRODUCTION...............................................................................................................................................6 3. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................................................................6 4. SITE DESCRIPTION.........................................................................................................................................7 5. HYDROLOGY.....................................................................................................................................................8 5.1. STAGE-DISCHARGE RATING CURVES .......................................................................................................9 5.2. PRECIPITATION........................................................................................................................................11 -

Gus Van Sant Retrospective Carte B

30.06 — 26.08.2018 English Exhibition An exhibition produced by Gus Van Sant 22.06 — 16.09.2018 Galleries A CONVERSATION LA TERRAZA D and E WITH GUS VAN SANT MAGNÉTICA CARTE BLANCHE PREVIEW OF For Gus Van Sant GUS VAN SANT’S LATEST FILM In the months of July and August, the Terrace of La Casa Encendida will once again transform into La Terraza Magnética. This year the programme will have an early start on Saturday, 30 June, with a double session to kick off the film cycle Carte Blanche for Gus Van Sant, a survey of the films that have most influenced the American director’s creative output, selected by Van Sant himself filmoteca espaÑola: for the exhibition. With this Carte Blanche, the director plunges us into his pecu- GUS VAN SANT liar world through his cinematographic and musical influences. The drowsy, sometimes melancholy, experimental and psychedelic atmospheres of his films will inspire an eclectic soundtrack RETROSPECTIVE that will fill with sound the sunsets at La Terraza Magnética. La Casa Encendida Opening hours facebook.com/lacasaencendida Ronda de Valencia, 2 Tuesday to Sunday twitter.com/lacasaencendida 28012 Madrid from 10 am to 10 pm. instagram.com/lacasaencendida T 902 430 322 The exhibition spaces youtube.com/lacasaencendida close at 9:45 pm vimeo.com/lacasaencendida blog.lacasaencendida.es lacasaencendida.es With the collaboration of Cervezas Alhambra “When I shoot my films, the tension between the story and abstraction is essential. Because I learned cinema through films made by painters. Through their way of reworking cinema and not sticking to the traditional rules that govern it. -

Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10Pm in the Carole L

Mike Traina, professor Petaluma office #674, (707) 778-3687 Hours: Tues 3-5pm, Wed 2-5pm [email protected] Additional days by appointment Media 10: Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10pm in the Carole L. Ellis Auditorium Course Syllabus, Spring 2017 READ THIS DOCUMENT CAREFULLY! Welcome to the Spring Cinema Series… a unique opportunity to learn about cinema in an interdisciplinary, cinematheque-style environment open to the general public! Throughout the term we will invite a variety of special guests to enrich your understanding of the films in the series. The films will be preceded by formal introductions and followed by public discussions. You are welcome and encouraged to bring guests throughout the term! This is not a traditional class, therefore it is important for you to review the course assignments and due dates carefully to ensure that you fulfill all the requirements to earn the grade you desire. We want the Cinema Series to be both entertaining and enlightening for students and community alike. Welcome to our college film club! COURSE DESCRIPTION This course will introduce students to one of the most powerful cultural and social communications media of our time: cinema. The successful student will become more aware of the complexity of film art, more sensitive to its nuances, textures, and rhythms, and more perceptive in “reading” its multilayered blend of image, sound, and motion. The films, texts, and classroom materials will cover a broad range of domestic, independent, and international cinema, making students aware of the culture, politics, and social history of the periods in which the films were produced. -

18 an Interdisciplinary and Hierarchical Approach to the Study and Management of River Ecosystems M

18 An Interdisciplinary and Hierarchical Approach to the Study and Management of River Ecosystems M. C. THOMS INTRODUCTION Rivers are complex ecosystems (Thoms & Sheldon, 2000a) influenced by prior states, multi-causal effects, and the states and dynamics of external systems (Walters & Korman, 1999). Rivers comprise at least three interacting subsystems (geomorphological, hydro- logical and ecological), whose structure and function have traditionally been studied by separate disciplines, each with their own paradigms and perspectives. With increasing pressures on the environment, there is a strong trend to manage rivers as ecosystems, and this requires a holistic, interdisciplinary approach. Many disciplines are often brought together to solve environmental problems in river systems, including hydrology, geomor- phology and ecology. Integration of different disciplines is fraught with challenges that can potentially reduce the effectiveness of interdisciplinary approaches to environmental problems. Pickett et al. (1994) identified three issues regarding interdisciplinary research: – gaps in understanding appear at the interface between disciplines; – disciplines focus on specific scales or levels or organization; and, – as sub-disciplines become rich in detail they develop their own view points, assumptions, definitions, lexicons and methods. Dominant paradigms of individual disciplines impede their integration and the development of a unified understanding of river ecosystems. Successful inter- disciplinary science and problem solving requires the joining of two or more areas of understanding into a single conceptual-empirical structure (Pickett et al., 1994). Frameworks are useful tools for achieving this. Established in areas of engineering, conceptual frameworks help define the bounds for the selection and solution of problems; indicate the role of empirical assumptions; carry the structural assumptions; show how facts, hypotheses, models and expectations are linked; and, indicate the scope to which a generalization or model applies (Pickett et al., 1994). -

Drugs Effect

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 9-1-1997 Drugs effect Daisy Fang Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Fang, Daisy, "Drugs effect" (1997). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rochester Institute of Technology A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the College of Imaging Arts and Sciences in candidacy for the degree of Master of Fine Arts. Drugs Effect by Daisy Fang September 1997 Approvals Chief Advisor: James Ver Hague Signature 7. /0. 17 Date Associate Advisor: Nancy A.Ciolek Signature 7· /c:J . 9 r Date Associate Advisor: Marla Schweppe Signature Date Department Chairperson: Nancy A.Ciolek Signature Date I, Daisy Fang, hereby grant permission to the Wallace Memorial library of RIT to repro duce my thesis in whole or in part. Any reproduction will not be commercial use or profit. Signature :;Q~ lO , eft-=--- _ Date ii mu azaizil daaAu CPauL^J-cmq, (Lhan-<z7TyuuiLQ C7TS. it the. bzsi. aiji iked, ojllL s.ve.1 kab.tin to rm. Dedication Lin hhz Jbh.,cLaL _y\/[,moxu or UL, O/ihtm (Wax*, in Cfana (1836 - jSgS) Special Memory IV Index Title Page Approval Dedication Special Memory iv Contents v Introduction 1 Inspiration Fictional Inspirations 2 Historical Inspirations 2 Societal Inspirations 3 Research Fictional Sources 4 Historical Sources 6 Societal Sources 8 Implementation Overview 1 2 Navigation Map 13 Procedure 3D Models Establishment 16 Movie Organization 20 After Effects Time Layout 24 Conclusion 28 Appendix Societal Sources 29 Poster and Death Chart 32 Drugs Effect 33 Bibliography 46 Credits 49 Index Introduction This thesis project is a 3 minutes 30 seconds computer gener ated animation that includes 2D graphics design, 2D animation, 3D modeling and animation. -

Finding Forrester Forrester – Gefunden! a La Rencontre De Forrester

Wettbewerb/IFB 2001 FINDING FORRESTER FORRESTER – GEFUNDEN! A LA RENCONTRE DE FORRESTER Regie: Gus Van Sant USA 2000 Darsteller William Forrester Sean Connery Länge 136 Min. Jamal Wallace Rob Brown Format 35 mm, Prof.Crawford F.Murray Abraham Cinemascope Claire Spence Anna Paquin Farbe Terrell Busta Rhymes Ms.Joyce April Grace Stabliste Coleridge Michael Pitt Buch Mike Rich Dr.Spence Michael Nouri Kamera Harris Savides Matthews Richad Easton Kameraführung Craig Haagensen Massie Glenn Fitzgerald Kameraassistenz Eric C.Swanek Damon Zane R.Copeland Jr. Michael Cambria Janice Stephanie Berry Caesar S.Carnevale Fly Fly Williams III Schnitt Valdis Oskarsdottir Kenzo Damany Mathis Schnittassistenz Helen Hand Clay Damien Lee Tonschnitt Kelley Baker Trainer Garrick Tom Kearns Tonassistenz Paul Koronkiewicz Hartwell Matthew Noah Word Alfredo Viteri Dr.Simon Charles Bernstein Mischung Brian Miksis Bradley Matt Malloy Musik Bill Brown Sean Connery, Rob Brown Foto:G.Kraychyk Sanderson Matt Damon Production Design Jane Musky Ausstattung Darrell K.Keister Kostüm Ann Roth FORRESTER – GEFUNDEN! Maske Michael Bigger Ein abbruchreifes Backsteinhaus in der South-Bronx. Zwischen den vielen Regieassistenz David Webb schmucklos in die Höhe gezogenen Mietskasernen ist dieser übrig geblie- Produktionsltg. Michele Giordano bene Bau ein Fremdkörper in der Gegend. Auf die schwarzen Kids, die auf Aufnahmeleitung Trish Adlesic dem Platz davor Basketball spielen, macht es einen geheimnisvollen Ein- Produzenten Laurence Mark Sean Connery druck – auch wegen des silberhaarigen alten Mannes, der das Haus nie zu Rhonda Tellefson verlassen scheint und immer hinter den blank geputzten Fenstern in der Executive Producers Dany Wolf dritten Etage zu sehen ist. Jamal, Basketball-Ass, Leseratte und überdurch- Jonathan King schnittlich intelligenter Bursche, der sein Licht im Kreise seiner Kumpels allerdings unter den Scheffel stellt, wird von den anderen dazu angesta- Produktion Fountainbridge Films chelt, in die ominöse Wohnung einzusteigen und sich dort mal umzu- c/o Columbia Tristar schauen. -

A Film Music Documentary

VULTURE PROUDLY SUPPORTS DOC NYC 2016 AMERICA’s lARGEST DOCUMENTARY FESTIVAL Welcome 4 Staff & Sponsors 8 Galas 12 Special Events 15 Visionaries Tribute 18 Viewfinders 20 Metropolis 24 American Perspectives 29 International Perspectives 33 True Crime 36 DEVOURING TV AND FILM. Science Nonfiction 38 Art & Design 40 @DOCNYCfest ALL DAY. EVERY DAY. Wild Life 43 Modern Family 44 Behind the Scenes 46 Schedule 51 Jock Docs 55 Fight the Power 58 Sonic Cinema 60 Shorts 63 DOC NYC U 68 Docs Redux 71 Short List 73 DOC NYC Pro 83 Film Index 100 Map, Pass and Ticket Information 102 #DOCNYC WELCOME WELCOME LET THE DOCS BEGIN! DOC NYC, America’s Largest Documentary hoarders and obsessives, among other Festival, has returned with another eight days fascinating subjects. of the newest and best nonfiction programming to entertain, illuminate and provoke audiences Building off our world premiere screening of in the greatest city in the world. Our seventh Making A Murderer last year, we’ve introduced edition features more than 250 films and panels, a new t rue CriMe section. Other fresh presented by over 300 filmmakers and thematic offerings include SceC i N e special guests! NONfiCtiON, engaging looks at the worlds of science and technology, and a rt & T HE C ITY OF N EW Y ORK , profiles of artists. These join popular O FFICE OF THE M AYOR This documentary feast takes place at our Design N EW Y ORK, NY 10007 familiar venues in Greenwich Village and returning sections: animal-focused THEl wi D Chelsea. The IFC Center, the SVA Theatre and life, unconventional MODerN faMilY Cinepolis Chelsea host our film screenings, while portraits, cinephile celebrations Behi ND the sCeNes, sports-themed JCO k DO s, November 10, 2016 Cinepolis Chelsea once again does double duty activism-oriented , music as the home of DOC NYC PrO, our panel f iGht the POwer and masterclass series for professional and doc strand Son iC CiNeMa and doc classic aspiring documentary filmmakers. -

SLENDER MAN PANIC Holly Vasic (Faculty Mentor Sean Lawson, Phd) Department of Communications

University of Utah UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH JOURNAL SLENDER MAN PANIC Holly Vasic (Faculty Mentor Sean Lawson, PhD) Department of Communications The last day of May, 2014, in the sleepy Midwest town of Waukesha Wisconsin, 12-year- old’s Morgan Geyser and Annissa Weier were discovered splattered with blood and walking along the interstate after stabbing a girl, they called their friend, 19 times. When asked why, they said that Slender Man, a creepy faceless figure from a website called Something Awful (www.somethingawful.com), made them do it (Blank, 2018). This crime was reported about all over the country, and abroad, by top media sources as well as discussed in blogs around the web. Using the existing research on the phenomenon of “moral panic,” my research investigates the extent to which news media reporting and parent responses to Slender Man qualify as a moral panic. To qualify, the mythical creature must be reported about in a way that perpetuates fear in a set of the population that believe the panic to be real (Krinsky, 2013). As my preliminary research indicated that Christian parenting blogs demonstrated a strong response to the Slender Man phenomenon, I will explore the subgenre of Christian parenting blogs to gauge the extent to which Slender Man was considered a real threat by this specific group. Thus, my primary research questions will include: Q1: To what degree do mainstream media portrayals of Slender Man fit the characteristics of a moral panic as defined in the academic research literature? Q2: In what ways do Christian parenting blogs echo, extend upon, or reject the moral panic framing of Slender Man in the mainstream media? Since the emergence of Slender Man, a decade ago, concerns about fake news, disinformation, and the power of visual “memes” to negatively shape society and politics have only grown.