Gibbons Et Al. 2000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Addo Elephant National Park Reptiles Species List

Addo Elephant National Park Reptiles Species List Common Name Scientific Name Status Snakes Cape cobra Naja nivea Puffadder Bitis arietans Albany adder Bitis albanica very rare Night adder Causes rhombeatus Bergadder Bitis atropos Horned adder Bitis cornuta Boomslang Dispholidus typus Rinkhals Hemachatus hemachatus Herald/Red-lipped snake Crotaphopeltis hotamboeia Olive house snake Lamprophis inornatus Night snake Lamprophis aurora Brown house snake Lamprophis fuliginosus fuliginosus Speckled house snake Homoroselaps lacteus Wolf snake Lycophidion capense Spotted harlequin snake Philothamnus semivariegatus Speckled bush snake Bitis atropos Green water snake Philothamnus hoplogaster Natal green watersnake Philothamnus natalensis occidentalis Shovel-nosed snake Prosymna sundevalli Mole snake Pseudapsis cana Slugeater Duberria lutrix lutrix Common eggeater Dasypeltis scabra scabra Dappled sandsnake Psammophis notosticus Crossmarked sandsnake Psammophis crucifer Black-bellied watersnake Lycodonomorphus laevissimus Common/Red-bellied watersnake Lycodonomorphus rufulus Tortoises/terrapins Angulate tortoise Chersina angulata Leopard tortoise Geochelone pardalis Green parrot-beaked tortoise Homopus areolatus Marsh/Helmeted terrapin Pelomedusa subrufa Tent tortoise Psammobates tentorius Lizards/geckoes/skinks Rock Monitor Lizard/Leguaan Varanus niloticus niloticus Water Monitor Lizard/Leguaan Varanus exanthematicus albigularis Tasman's Girdled Lizard Cordylus tasmani Cape Girdled Lizard Cordylus cordylus Southern Rock Agama Agama atra Burrowing -

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History Database

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History database Abdala, C. S., A. S. Quinteros, and R. E. Espinoza. 2008. Two new species of Liolaemus (Iguania: Liolaemidae) from the puna of northwestern Argentina. Herpetologica 64:458-471. Abdala, C. S., D. Baldo, R. A. Juárez, and R. E. Espinoza. 2016. The first parthenogenetic pleurodont Iguanian: a new all-female Liolaemus (Squamata: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. Copeia 104:487-497. Abdala, C. S., J. C. Acosta, M. R. Cabrera, H. J. Villaviciencio, and J. Marinero. 2009. A new Andean Liolaemus of the L. montanus series (Squamata: Iguania: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. South American Journal of Herpetology 4:91-102. Abdala, C. S., J. L. Acosta, J. C. Acosta, B. B. Alvarez, F. Arias, L. J. Avila, . S. M. Zalba. 2012. Categorización del estado de conservación de las lagartijas y anfisbenas de la República Argentina. Cuadernos de Herpetologia 26 (Suppl. 1):215-248. Abell, A. J. 1999. Male-female spacing patterns in the lizard, Sceloporus virgatus. Amphibia-Reptilia 20:185-194. Abts, M. L. 1987. Environment and variation in life history traits of the Chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus. Ecological Monographs 57:215-232. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2003. Anfibios y reptiles del Uruguay. Montevideo, Uruguay: Facultad de Ciencias. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2007. Anfibio y reptiles del Uruguay, 3rd edn. Montevideo, Uruguay: Serie Fauna 1. Ackermann, T. 2006. Schreibers Glatkopfleguan Leiocephalus schreibersii. Munich, Germany: Natur und Tier. Ackley, J. W., P. J. Muelleman, R. E. Carter, R. W. Henderson, and R. Powell. 2009. A rapid assessment of herpetofaunal diversity in variously altered habitats on Dominica. -

Evolution of Limblessness

Evolution of Limblessness Evolution of Limblessness Early on in life, many people learn that lizards have four limbs whereas snakes have none. This dichotomy not only is inaccurate but also hides an exciting story of repeated evolution that is only now beginning to be understood. In fact, snakes represent only one of many natural evolutionary experiments in lizard limblessness. A similar story is also played out, though to a much smaller extent, in amphibians. The repeated evolution of snakelike tetrapods is one of the most striking examples of parallel evolution in animals. This entry discusses the evolution of limblessness in both reptiles and amphibians, with an emphasis on the living reptiles. Reptiles Based on current evidence (Wiens, Brandley, and Reeder 2006), an elongate, limb-reduced, snakelike morphology has evolved at least twenty-five times in squamates (the group containing lizards and snakes), with snakes representing only one such origin. These origins are scattered across the evolutionary tree of squamates, but they seem especially frequent in certain families. In particular, the skinks (Scincidae) contain at least half of all known origins of snakelike squamates. But many more origins within the skink family will likely be revealed as the branches of their evolutionary tree are fully resolved, given that many genera contain a range of body forms (from fully limbed to limbless) and may include multiple origins of snakelike morphology as yet unknown. These multiple origins of snakelike morphology are superficially similar in having reduced limbs and an elongate body form, but many are surprisingly different in their ecology and morphology. This multitude of snakelike lineages can be divided into two ecomorphs (a are surprisingly different in their ecology and morphology. -

Annexure I Fauna & Flora Assessment.Pdf

Fauna and Flora Baseline Study for the De Wittekrans Project Mpumalanga, South Africa Prepared for GCS (Pty) Ltd. By Resource Management Services (REMS) P.O. Box 2228, Highlands North, 2037, South Africa [email protected] www.remans.co.za December 2008 I REMS December 2008 Fauna and Flora Assessment De Wittekrans Executive Summary Mashala Resources (Pty) Ltd is planning to develop a coal mine south of the town of Hendrina in the Mpumalanga province on a series of farms collectively known as the De Wittekrans project. In compliance with current legislation, they have embarked on the process to acquire environmental authorisation from the relevant authorities for their proposed mining activities. GCS (Pty) Ltd. commissioned Resource Management Services (REMS) to conduct a Faunal and Floral Assessment of the area to identify the potential direct and indirect impacts of future mining, to recommend management measures to minimise or prevent these impacts on these ecosystems and to highlight potential areas of conservation importance. This is the wet season survey which was done in the November 2008. The study area is located within the highveld grasslands of the Msukaligwa Local Municipality in the Gert Sibande District Municipality in Mpumalanga Province on the farms Tweefontein 203 IS (RE of Portion 1); De Wittekrans 218 IS (RE of Portion 1 and Portion 2, Portions 7, 11, 10 and 5); Groblershoek 191 IS; Groblershoop 192 IS; and Israel 207 IS. Within this region, precipitation occurs mainly in the summer months of October to March with the peak of the rainy season occurring from November to January. -

June 28, 1859. Dr. Gray, FRS, VP, in the Chair. the Following

213 June 28, 1859. Dr. Gray, F.R.S., V.P., in the Chair. The following papers were read :- I. NOTESON THE DUCK-BILL(ORNITHORHYNCHUS ANATIXU~). BY UR. GEORGEBENNETT, P.Z.S. (Mammalia, P1. LXXI.) On the morning of the 14th of September, 1848, I received through the kindness of Henry Brooks, Esq., of Penrith, six speci- mens of the Omithorhynchus-an unusually large number to be captured and sent at one time-consisting of four full-grown inales and two full-grown females. As usual, the latter were much smaller in size than the former. Some of these animals had been shot, and others captured in nets at night, at a place named Robe’s Creek, near the South Creek, Penrith, about thirty miles from Sydney. They were all in good and fresh condition, excepting one of the fe- males, in which some degree of decomposition had taken place, but not sufficient to prevent examination. On dissection, I found the uteri of the females (although it was the commencement of the breeding season) unimpregnated ; but in the four males the testes were all enlarged, resembling pigeons’ eggs in size, and of a pure white colour. At other seasons of the year I have observed them in these animals not larger than a small pea, and this being the commence- ment of the breeding season could alone account for their size ; so that they show in this respect a great resemblance to what is observed in most birds during the breeding season of the year. I am not aware of this peculiarity existing in any other Mammalia. -

The Global Decline of Reptiles, Deja Vu Amphibians

Articles The Global Decline of Reptiles,Dé jà Vu Amphibians J. WHITFIELD GIBBONS,DAVID E. SCOTT,T R AVIS J. RYA N ,KURT A. B U H L M A N N ,T R ACEY D. TUBERV I L L E ,BRIAN S. METTS,J UDITH L. GREENE, TONY MILLS,YALE LEIDEN, SEAN POPPY,AND CHRISTOPHER T. WINNE s a group [reptiles] are neit h er ‘good ’n or ‘bad , ’ but “ ia re interes ting and unu sua l , a lt h o u gh of mi nor A i m porta n ce . If th ey should all disappe ar , it wo ul d REP TI L E SPE CI E S AR E DE CL I N IN G ON A not make mu ch difference one way or the other ”( Zim and Smith 1953,p. 9) . Fortu n a tely,this op i n i on from the Golden GLO BA L SC A L E. SI XS I G N I F IC A N T TH R E ATS Gu ide Series does not persist tod ay;most people have com e TOR E P T I L EPO P ULA T I O N SAR E H A BI T AT to recogn i ze the va lue ofboth reptiles and amphi bians as an in tegral part ofn a tu ral eco sys tems and as heralds of LO SS A N DD E G RADA TI O N , I N T RO D U C E D environ m ental qu a l ity (Gibbons and Stangel 1999). -

Describing Species

DESCRIBING SPECIES Practical Taxonomic Procedure for Biologists Judith E. Winston COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK Columbia University Press Publishers Since 1893 New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © 1999 Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data © Winston, Judith E. Describing species : practical taxonomic procedure for biologists / Judith E. Winston, p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-231-06824-7 (alk. paper)—0-231-06825-5 (pbk.: alk. paper) 1. Biology—Classification. 2. Species. I. Title. QH83.W57 1999 570'.1'2—dc21 99-14019 Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. Printed in the United States of America c 10 98765432 p 10 98765432 The Far Side by Gary Larson "I'm one of those species they describe as 'awkward on land." Gary Larson cartoon celebrates species description, an important and still unfinished aspect of taxonomy. THE FAR SIDE © 1988 FARWORKS, INC. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Universal Press Syndicate DESCRIBING SPECIES For my daughter, Eliza, who has grown up (andput up) with this book Contents List of Illustrations xiii List of Tables xvii Preface xix Part One: Introduction 1 CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 3 Describing the Living World 3 Why Is Species Description Necessary? 4 How New Species Are Described 8 Scope and Organization of This Book 12 The Pleasures of Systematics 14 Sources CHAPTER 2. BIOLOGICAL NOMENCLATURE 19 Humans as Taxonomists 19 Biological Nomenclature 21 Folk Taxonomy 23 Binomial Nomenclature 25 Development of Codes of Nomenclature 26 The Current Codes of Nomenclature 50 Future of the Codes 36 Sources 39 Part Two: Recognizing Species 41 CHAPTER 3. -

The Herpetofauna of the Cubango, Cuito, and Lower Cuando River Catchments of South-Eastern Angola

Official journal website: Amphibian & Reptile Conservation amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 10(2) [Special Section]: 6–36 (e126). The herpetofauna of the Cubango, Cuito, and lower Cuando river catchments of south-eastern Angola 1,2,*Werner Conradie, 2Roger Bills, and 1,3William R. Branch 1Port Elizabeth Museum (Bayworld), P.O. Box 13147, Humewood 6013, SOUTH AFRICA 2South African Institute for Aquatic Bio- diversity, P/Bag 1015, Grahamstown 6140, SOUTH AFRICA 3Research Associate, Department of Zoology, P O Box 77000, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, Port Elizabeth 6031, SOUTH AFRICA Abstract.—Angola’s herpetofauna has been neglected for many years, but recent surveys have revealed unknown diversity and a consequent increase in the number of species recorded for the country. Most historical Angola surveys focused on the north-eastern and south-western parts of the country, with the south-east, now comprising the Kuando-Kubango Province, neglected. To address this gap a series of rapid biodiversity surveys of the upper Cubango-Okavango basin were conducted from 2012‒2015. This report presents the results of these surveys, together with a herpetological checklist of current and historical records for the Angolan drainage of the Cubango, Cuito, and Cuando Rivers. In summary 111 species are known from the region, comprising 38 snakes, 32 lizards, five chelonians, a single crocodile and 34 amphibians. The Cubango is the most western catchment and has the greatest herpetofaunal diversity (54 species). This is a reflection of both its easier access, and thus greatest number of historical records, and also the greater habitat and topographical diversity associated with the rocky headwaters. -

Khutala 5-Seam Mining Project: Mpumalanga Province Terrestrial

Author: Barbara Kasl E-mail: [email protected] Khutala 5-Seam Mining Project: Mpumalanga Province Terrestrial Fauna Biodiversity Impact Assessment May 2021 Copyright is the exclusive property of the author. All rights reserved. This report or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express permission of the author except for the use of quotations properly cited and referenced. This document may not be modified other than by the author. Khutala 5-Seam Mining Project: Terrestrial Fauna Impact Assessment Report May 2021 Specialist Qualification & Declaration Barbara Kasl (CV summary attached as Appendix A): • Holds a PhD in Animal, Plant and Environmental Sciences from the University of the Witwatersrand; • Is a registered SACNASP Professional Ecological and Environmental Scientist (Pr.Sci.Nat. Registration No.: 400257/09), with expertise in faunal ecology; and • Has been actively involved in the environmental consultancy field for over 13 years. I, Barbara Kasl, confirm that: • I act as independent consultant and specialist in the field of ecology and environmental sciences; • I have no vested interest in the project other than remuneration for work completed in terms of the Scope of Work; • I have presented the information in this report in line with the requirements of the Animal Species and Terrestrial Biodiversity Protocols as required under the National Environmental Management Act (107/1998) (NEMA) as far as these are relevant to the specific Scope of Work; • I have taken NEMA Principals into account as far as these are relevant to the Scope of Work; and • Information presented is, to the best of my knowledge, accurate and correct within the restraints of stipulated limitations. -

Squamata, Gymnophthalmidae)

Phyllomedusa 3(2):83-94, 2004 © 2004 Melopsittacus Publicações Científicas ISSN 1519-1397 High frequency of pauses during intermittent locomotion of small South American gymnophthalmid lizards (Squamata, Gymnophthalmidae) Elizabeth Höfling1 and Sabine Renous2 1 Departamento de Zoologia, Instituto de Biociências, Universidade de São Paulo, Rua do Matão, Travessa 14, n° 321, 05508-900, São Paulo, SP, Brazil. E-mail: [email protected]. 2 USM 302, Département d’Ecologie et Gestion de la Biodiversité, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, 55 rue Buffon, 75005, Paris, France. Abstract High frequency of pauses during intermittent locomotion of small South American gymnophthalmid lizards (Squamata, Gymnophthalmidae). We studied the locomotor behavior of two closely-related species of Gymnophthalmini lizards, Vanzosaura rubricauda and Procellosaurinus tetradactylus, that was imaged under laboratory conditions at a rate of 250 frames/s with a high-speed video camera (MotionScope PCI 1000) on four different substrates with increasing degrees of roughness (smooth perspex, cardboard, glued sand, and glued gravel). Vanzosaura rubricauda and P. tetradactylus are both characterized by intermittent locomotion, with pauses occurring with high frequency and having a short duration (from 1/10 to 1/3 s), and taking place in rhythmic locomotion in an organized fashion during all types of gaits and on different substrates. The observed variations in duration and frequency of pauses suggest that in V. rubricauda mean pause duration is shorter and pause frequency is higher than in P. tetradactylus. The intermittent locomotion observed in V. rubricauda and P. tetradactylus imaging at 250 frames/s is probably of interest for neurobiologists. In the review of possible determinants, the phylogenetic relationships among the species of the tribe Gymnophthalmini are focused. -

Short Communications

214 S. Afc. J. Zool. 1996.31(4) Short communications not proposed in the absence of a series of specimens which can serve to define variation in the subspecies, especially as so little is known about variation within the nominate race'. Taxonomic status and distribution of the Bourquin & Channing (1980) later recorded a specimen of T South African lizard Tetradactylus breyeri bre.veri from Cathedral Peak Forest Reserve in KwaZulu Natal. while Jacobsen (1989) described two specimens col Roux (Gerrhosauridae) lected in Mpumalanga province. Specimens from the farm Stratherrick in the north-eastern Free State were briefly dis M.F. Bates cussed by Bates (1993a). In the present study variation in morphology and scutella Department of Herpetology. National Museum. P.O. Box 266. tion in the 15 known specimens of T. breyeri was examined, Bloemfontein 9300. South Africa and De Waal's (1978) proposal that the Zwartkoppies speci men represents a distinct subspecies was re-evaluated. The Received 3 April/996; accepted 11 November 1996 distribution, habitat and conservation status of T. breyeri were The taxonomic status of the poorly known South African also studied. gerrhosaurid Tetradactylus breyeri. described by Roux in 1907 The holotype. housed in the Zoologisch Museum at the on the basis of a single specimen from the Transvaal, was University of Amsterdam (The Netherlands). together with all investigated. The holotype and 14 other preserved specimens 14 available specimens of T breyeri in southern African were examined and are described in detail. Prior to this study. museums and private collections, was examined (Appendix only six specimens had been described in the literature. -

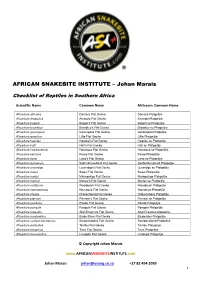

Johan Marais

AFRICAN SNAKEBITE INSTITUTE – Johan Marais Checklist of Reptiles in Southern Africa Scientific Name Common Name Afrikaans Common Name Afroedura africana Damara Flat Gecko Damara Platgeitjie Afroedura amatolica Amatola Flat Gecko Amatola Platgeitjie Afroedura bogerti Bogert's Flat Gecko Bogert se Platgeitjie Afroedura broadleyi Broadley’s Flat Gecko Broadley se Platgeitjie Afroedura gorongosa Gorongosa Flat Gecko Gorongosa Platgeitjie Afroedura granitica Lillie Flat Gecko Lillie Platgeitjie Afroedura haackei Haacke's Flat Gecko Haacke se Platgeitjie Afroedura halli Hall's Flat Gecko Hall se Platgeitjie Afroedura hawequensis Hawequa Flat Gecko Hawequa se Platgeitjie Afroedura karroica Karoo Flat Gecko Karoo Platgeitjie Afroedura langi Lang's Flat Gecko Lang se Platgeitjie Afroedura leoloensis Sekhukhuneland Flat Gecko Sekhukhuneland Platgeitjie Afroedura loveridgei Loveridge's Flat Gecko Loveridge se Platgeitjie Afroedura major Swazi Flat Gecko Swazi Platgeitjie Afroedura maripi Mariepskop Flat Gecko Mariepskop Platgeitjie Afroedura marleyi Marley's Flat Gecko Marley se Platgeitjie Afroedura multiporis Woodbush Flat Gecko Woodbush Platgeijtie Afroedura namaquensis Namaqua Flat Gecko Namakwa Platgeitjie Afroedura nivaria Drakensberg Flat Gecko Drakensberg Platgeitjie Afroedura pienaari Pienaar’s Flat Gecko Pienaar se Platgeitjie Afroedura pondolia Pondo Flat Gecko Pondo Platgeitjie Afroedura pongola Pongola Flat Gecko Pongola Platgeitjie Afroedura rupestris Abel Erasmus Flat Gecko Abel Erasmus platgeitjie Afroedura rondavelica Blyde River