Midline Findings from the Evaluation of the Ananya Program in Bihar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brief Industrial Profile of ARWAL District

Government of India Ministry of MSME Brief Industrial Profile of ARWAL District Carried out by MSME-Development Institute (Ministry of MSME, Govt. of India,) Patliputra Industrial Estate, Patna-13 Phone:- 0612-2262719, 2262208, 2263211 Fax: 0612-2262186 e-mail: [email protected] Web- www.msmedipatna.gov.in 1 Contents S. No. Topic Page No. 1. General Characteristics of the District 3 1.1 Location & Geographical Area 3 1.2 Topography 3 1.3 Availability of Minerals. 3 1.4 Forest 4 1.5 Administrative set up 4 2. District at a glance 4 2.1 Existing Status of Industrial Area in the District -------- 7 3. Industrial Scenario Of --------- 8 3.1 Industry at a Glance 8 3.2 Year Wise Trend Of Units Registered 8 3.3 Details Of Existing Micro & Small Enterprises & Artisan Units In The 9 District 3.4 Large Scale Industries / Public Sector undertakings 10 3.5 Major Exportable Item 10 3.6 Growth Trend 10 3.7 Vendorisation / Ancillarisation of the Industry 10 3.8 Medium Scale Enterprises 10 3.8.1 List of the units in ------ & near by Area 10 3.8.2 Major Exportable Item 10 3.9 Service Enterprises 10 3.9.2 Potentials areas for service industry 11 3.10 Potential for new MSMEs 11 4. Existing Clusters of Micro & Small Enterprise 11 4.1 Detail Of Major Clusters 11 4.1.1 Manufacturing Sector 11 4.1.2 Service Sector 11 4.2 Details of Identified cluster 11 5. General issues raised by industry association during the course of 11 meeting 6 Steps to set up MSMEs 12 2 Brief Industrial Profile of Arwal District 1. -

Of India 100935 Parampara Foundation Hanumant Nagar ,Ward No

AO AO Name Address Block District Mobile Email Code Number 97634 Chandra Rekha Shivpuri Shiv Mandir Road Ward No 09 Araria Araria 9661056042 [email protected] Development Foundation Araria Araria 97500 Divya Dristi Bharat Divya Dristi Bharat Chitragupt Araria Araria 9304004533 [email protected] Nagar,Ward No-21,Near Subhash Stadium,Araria 854311 Bihar Araria 100340 Maxwell Computer Centre Hanumant Nagar, Ward No 15, Ashram Araria Araria 9934606071 [email protected] Road Araria 98667 National Harmony Work & Hanumant Nagar, Ward No.-15, Po+Ps- Araria Araria 9973299101 [email protected] Welfare Development Araria, Bihar Araria Organisation Of India 100935 Parampara Foundation Hanumant Nagar ,Ward No. 16,Near Araria Araria 7644088124 [email protected] Durga Mandir Araria 97613 Sarthak Foundation C/O - Taranand Mishra , Shivpuri Ward Araria Araria 8757872102 [email protected] No. 09 P.O + P.S - Araria Araria 98590 Vivekanand Institute Of 1st Floor Milan Market Infront Of Canara Araria Araria 9955312121 [email protected] Information Technology Bank Near Adb Chowk Bus Stand Road Araria Araria 100610 Ambedkar Seva Sansthan, Joyprakashnagar Wardno-7 Shivpuri Araria Araria 8863024705 [email protected] C/O-Krishnamaya Institute Joyprakash Nagar Ward No -7 Araria Of Higher Education 99468 Prerna Society Of Khajuri Bazar Araria Bharga Araria 7835050423 [email protected] Technical Education And ma Research 100101 Youth Forum Forbesganj Bharga Araria 7764868759 [email protected] -

Brief Industrial Profile of PURNEA District

P a g e | 1 G o v e r n m e n t o f I n d i a M in is t r y of M S M E Brief Industrial Profile of PURNEA District Carried out by MS ME - D e v e l opme nt I ns ti tute , M uz a ff a r pur (Ministry of MSME, Govt. of India,) Phone :-0621-2284425 Fax: 0621-2282486 e-mail:[email protected] Web- www.msmedimzfpur.bih.nic.in Page | 2 Contents S. No. Topic Page No. 1. General Characteristics of the District 3 1.1 Location & Geographical Area 4 1.2 Topography 5-6 1.3 Availability of Minerals. 7 1.4 Forest 8 1.5 Administrative set up 8-9 2. District at a glance 9-14 2.1 Existing Status of Industrial Area in the District Purnia 14 3. Industrial Scenario Of Purnia 15 3.1 Industry at a Glance - 3.2 Year Wise Trend Of Units Registered 16 3.3 Details Of Existing Micro & Small Enterprises & Artisan Units In The 17 District 3.4 Large Scale Industries / Public Sector undertakings 18 3.5 Major Exportable Item 18 3.6 Growth Trend 18 3.7 Vendorisation / Ancillarisation of the Industry 18 3.8 Medium Scale Enterprises 18 3.8.1 List of the units in –PURNEA ---- & near by Area 18 3.8.2 Major Exportable Item 18 3.9.1 Coaching Industry 19 3.9.2 Potentials areas for service industry 19 3.10 Potential for new MSMEs 19 4. -

State District Name of Bank Bank Branch/ Financial Literacy Centre

State District Name of Bank Branch/ Address ITI Code ITI Name ITI Address State District Phone Email Bank Financial Category Number Literacy Centre Bihar Araria State Araria Lead Bank Office, PR10000055 Al-Sahaba Industrial P Alamtala Forbesganj Bihar Araria NULL Bank of ADB Building, Training Institute India Araria, Pin- 854311 Bihar Arwal PNB ARWAL ARWAL PR10000083 Adarsh ITC P Umerabad Bihar Arwal NULL Bihar Arwal PNB ARWAL ARWAL PR10000284 Shakuntalam ITC P Prasadi English Bihar Arwal NULL Bihar Arwal PNB ARWAL ARWAL PR10000346 Aditya ITC P At. Wasilpur, Main Road, Bihar Arwal NULL P.O. Arwal, Bihar Arwal PNB ARWAL ARWAL PR10000396 Vikramshila Private P At. Rojapar, P.O. Arwal Bihar Arwal NULL ITI Bihar Arwal PNB ARWAL ARWAL PR10000652 Ram Bhaman Singh P At-Purani Bazar P.o+P.S- Bihar Arwal NULL Private ITI Arwal Bihar Arwal PNB ARWAL ARWAL PR10000677 Sukhdeo Institute Of P Kurtha, Arwal Bihar Arwal NULL Tecnology Private ITI, Bihar Arwal PNB ARWAL ARWAL PR10000707 Dr. Rajendra Prasad P Mubarkpur, Kurtha Arwal Bihar Arwal NULL Private ITI, Bihar Aurangabad PUNJAB DAUDNAGAR DAUDNAGAR PR10000027 New Sai Private ITI- P Aurangabad Road, Bihar Aurangabad NULL NATIONA Bhakharuan More, , Tehsil- L BANK Daudnagar , , Aurangabad - 824113 Bihar Aurangabad PUNJAB AURANGABAD AURANGABAD PR10000064 Adharsh Industrial P Josai More Udyog Bihar Aurangabad NULL NATIONA Training Centre Pradhikar Campus L BANK Bihar Aurangabad MADHYA DAUDNAGAR DAUDNAGAR PR10000108 Sardar Vallabh Bhai P Daudnagar Bihar Aurangabad NULL BIHAR Patel ITC, Daudnagar GRAMIN BANK Bihar Aurangabad MADHYA DAUDNAGAR DAUDNAGAR PR10000142 Adarsh ITC, P AT-,Growth centre ,Jasoia Bihar Aurangabad NULL BIHAR Daudnagar More Daudnagar GRAMIN BANK Bihar Aurangabad PUNJAB RATANUA RATANUA PR10000196 Progresive ITC P At-Growth Center Josia Bihar Aurangabad NULL NATIONA More L BANK Bihar Aurangabad MADHYA DAUDNAGAR DAUDNAGAR PR10000199 Arya Bhatt ITC P Patel Nagar, Daud Nagar Bihar Aurangabad NULL BIHAR GRAMIN BANK Bihar Aurangabad PUNJAB OLD GT RD. -

National Family Health Survey (Nfhs-5) India 2019-20 Bihar

NATIONAL FAMILY HEALTH SURVEY (NFHS-5) INDIA 2019-20 National Family Health 2019-20 Survey (NFHS-5) BIHAR MARCH 2021 Suggested citation: International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF. 2021. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), India, 2019-20: Bihar. Mumbai: IIPS. For additional information about the 2019-20 National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), please contact: International Institute for Population Sciences, Govandi Station Road, Deonar, Mumbai-400088 Telephone: 022-4237 2442 Email: [email protected], [email protected] For related information, visit http://www.rchiips.org/nfhs or http://www.iipsindia.ac.in CONTRIBUTORS S.K. Singh Laxmi Kant Dwivedi Chander Shekhar Brajesh CONTENTS Page KEY FINDINGS Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 1 Household Characteristics ...................................................................................................................... 3 Education ................................................................................................................................................... 6 Fertility ...................................................................................................................................................... 7 Family Planning ..................................................................................................................................... 10 Infant and Child Mortality ................................................................................................................... -

Assets Employees 2020.Xlsx

GPF/CPF DDO Name of Employee's Employee's Name of the Date of Birth Home District PSUName DDO Designation /PRAN_ Cadre Code Employee Designation Department Office (DD/MM/YYYY) District Grade NO Gender AGRICULTURAL PROJECT BIHAR DISTRICT TECHNOLOGY ARVIND DIRECTOR BHRAGR AGRICULT Jehanabad ATMA 000000 AGRICULTURE ATMA MANAGEMENT M 26/03/1965 II PATNA KUMAR ATMA, 1259 URE OFFICER JEHANABAD AGENCY, ATMA JEHANABAD SERVICE JEHANABAD EXECUTIVE ENGINEER ELECTRIC SWITCH BIHAR STATE POWER ABHAY SWITCH BIHAR STATE POWER POWER HOLDING SUPPLY BOARD Jehanabad (HOLDING) COMPANY 000000 KUMAR BUTTON (HOLDING) SA69 M 05/03/1972 III Jehanabad COMPANY LIMITED DIVISION, OPERATO LIMITED SHARMA OPERATOR II COMPANY LIMITED JEHANABAD JEHANABAD R EXECUTIVE ENGINEER ELECTRIC BIHAR STATE POWER BIHAR STATE POWER POWER HOLDING ADITYA SUPPLY MESA70 ELECTRICI Jehanabad (HOLDING) COMPANY 000000 ELECTRICIAN (HOLDING) M 02/03/1964 III Jehanabad COMPANY LIMITED PRASAD DIVISION, 10 AN LIMITED COMPANY LIMITED JEHANABAD JEHANABAD EXECUTIVE ENGINEER ELECTRIC BIHAR STATE POWER JUNIOR BIHAR STATE POWER POWER HOLDING SUPPLY 1100348 JUNIOR Jehanabad (HOLDING) COMPANY 000000 AJAY KUMAR ELECTRICAL (HOLDING) M 12/06/1990 II Patna COMPANY LIMITED DIVISION, 29006 ENGINEER LIMITED ENGINEER COMPANY LIMITED JEHANABAD JEHANABAD EXECUTIVE ENGINEER ELECTRIC BIHAR STATE POWER JUNIOR BIHAR STATE POWER JUNIOR POWER HOLDING AMBER NATH SUPPLY CEPESU3 Jehanabad (HOLDING) COMPANY 000000 ACCOUNT (HOLDING) M 22/07/1970 ACCOUNT III Gaya COMPANY LIMITED CHATTERJEE DIVISION, 29 LIMITED CLERK COMPANY -

Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana CUCPL - Comprehensive Up-Gradation Cum Consolidation Priority List

Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana CUCPL - Comprehensive Up-gradation cum Consolidation Priority List State : Bihar District : All Districts Block : All Blocks Sr.No. State District Block Plan CN Plan Road Name Plan Road Route Educati Medical Veterin Transp Market Administ Populatio Total Score Per Avg PCI Road No. Length Priority onal Faciliti ary ort and Faciliti rative n Score Unit Services es Facilitie Commu es Centres Length s nicatio n Infrastr ucture 1 Bihar Arwal Arwal MRL01 Walidad, T01 To Khamhaini 10.835 M 12 0 0.00 0.00 0.00 1 68 81.00 7.48 1.00 2 Bihar Arwal Banshi MRL02 Manjhiyama to Khatangi 9.465 M 16 8 0.00 9.00 0.00 1 77 111.00 11.73 1.00 Surajpur 3 Bihar Arwal Banshi MRL03 Kharasi to Belaura 14.943 M 22 8 0.00 3.00 0.00 1 89 123.00 8.23 1.00 Surajpur 4 Bihar Arwal Banshi MRL01 Khatangi senari RD to Mobarakpur 10.860 M 9 4 0.00 3.00 0.00 1 42 59.00 5.43 1.00 Surajpur 5 Bihar Arwal Kaler MRL01 Sohasa Road L037 To Masadpur 21.676 M 10 6 0.00 6.00 0.00 1 54 77.00 3.55 1.00 6 Bihar Arwal Karpi MRL02 Imamganj Deokund Road,T04 To Jonha 7.365 M 22 8 3.00 11.00 9.00 2 91 146.00 19.82 1.00 7 Bihar Arwal Karpi MRL01 Karpi Barahmile Road, T03 To Salarpur 12.365 M 18 6 0.00 9.00 7.00 2 104 146.00 11.81 1.00 8 Bihar Arwal Karpi MRL03 Arwal Jehanabad Road, T02 To Aiyara 16.787 M 7 0 0.00 0.00 7.00 1 52 67.00 3.99 1.00 9 Bihar Arwal Kurtha MRL02 Salarpur L042, To Dhamaul 15.238 M 9 4 0.00 3.00 7.00 2 88 113.00 7.42 1.00 10 Bihar Arwal Kurtha MRL01 Pinjrawan to Manepaker 9.456 M 8 2 0.00 0.00 0.00 1 55 66.00 6.98 1.00 11 Bihar Aurangabad -

Observed Rainfall Variability and Changes Over Bihar State

CLIMATE RESEARCH AND SERVICES INDIA METEOROLOGICAL DEPARTMENT MINISTRY OF EARTH SCIENCES PUNE Observed Rainfall Variability and Changes over Bihar State Met Monograph No. : ESSO/IMD/HS/Rainfall Variability/04(2020)/28 Pulak Guhathakurta, Sudeepkumar B L, Preetha Menon, Ashwini Kumar Prasad, Neha Sangwan and S C Advani GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF EARTH SCIENCES INDIA METEOROLOGICAL DEPARTMENT Met Monograph No.: ESSO/IMD/HS/Rainfall Variability/04(2020)/28 Observed Rainfall Variability and Changes Over Bihar State Pulak Guhathakurta, Sudeepkumar B L, Preetha Menon, Ashwini Kumar Prasad, Neha Sangwan and S C Advani INDIA METEOROLOGICAL DEPARTMENT PUNE - 411005 1 DOCUMENT AND DATA CONTROL SHEET 1 Document Title Observed Rainfall Variability and Changes Over Bihar State 2 Issue No. ESSO/IMD/HS/Rainfall Variability/04(2020)/28 3 Issue Date January 2020 4 Security Unclassified Classification 5 Control Status Uncontrolled 6 Document Type Scientific Publication 7 No. of Pages 27 8 No. of Figures 42 9 No. of References 4 10 Distribution Unrestricted 11 Language English 12 Authors Pulak Guhathakurta, Sudeepkumar B L, Preetha Menon, Ashwini Kumar Prasad, Neha Sangwan and S C Advani 13 Originating Division/ Climate Research Division/ Climate Application & Group User Interface Group/ Hydrometeorology 14 Reviewing and Director General of Meteorology, India Approving Authority Meteorological Department, New Delhi 15 End users Central and State Ministries of Water resources, agriculture and civic bodies, Science and Technology, Disaster Management Agencies, Planning Commission of India 16 Abstract India is in the tropical monsoon zone and receives plenty of rainfall as most of the annual rainfall during the monsoon season every year. However, the rainfall is having high temporal and spatial variability and due to the impact of climate changes there are significant changes in the mean rainfall pattern and their variability as well as in the intensity and frequencies of extreme rainfall events. -

(SJAMS) Studies on Urinary Risk Factors in Urolithiasis Patients Of

Scholars Journal of Applied Medical Sciences (SJAMS) ISSN 2320-6691 (Online) Abbreviated Key Title: Sch. J. App. Med. Sci. ISSN 2347-954X (Print) ©Scholars Academic and Scientific Publisher A Unit of Scholars Academic and Scientific Society, India Chemistry www.saspublisher.com Studies on Urinary Risk Factors in Urolithiasis Patients of Purnia Division of Bihar, India T.V.R.K. Rao*, Gunja Kumari Department of Chemistry, Purnea College, Purnia-854301 Bihar, India Abstract: Urolithiasis disease is a function of a number of risk factors. Present Original Research Article objective is to study the urinary risk factors in urolithiasis patients from Purnia division of Bihar (India). The study would lead to an understanding of the various metabolic *Corresponding author abnormalities leading to urinary stone formation in this region. Twenty four hour T.V.R.K. Rao urinary calcium, magnesium, oxalate, phosphate, uric acid and citrate were estimated in 100 urolithiasis patients (66 males & 34 females) in the age group of 18-55 yrs. Fifty Article History normal healthy persons (30 males & 20 females) in the age group of 20-55 yrs, who Received: 01.08.2018 served as controls, were also studied for the above urinary parameters. Results revealed Accepted: 05.08.2018 that hypercalciuria, hyperoxaluria and hypocitraturia are the main risk factors of Published: 30.08.2018 urolithiasis in the region. Hyperuricosuria, hypophosphaturia and hypomagnesuria also showed up as marginal risk factors in the urinary stone patients. As such, urolithiasis DOI: patient from Purnia division of Bihar should invariably be tested for urinary calcium, 10.21276/sjams.2018.6.8.28 oxalate and citrate levels. -

Business Plan for Makhana Clusters in Bihar

Business Plan for Makhana Clusters in Bihar 1 INDEX BUSINESS PLAN FOR MAKHANA CLUSTERS IN BIHAR .................................... 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................. 4 Botany ......................................................................................................................... 8 Distribution and Habitat ............................................................................................. 9 Nutritional Value ...................................................................................................... 10 Uses ........................................................................................................................... 10 Cultivation and Harvesting of Makhana................................................................... 10 Processing of Makhana............................................................................................. 11 OBJECTIVE ..................................................................................................................... 12 APPROACH & METHODOLOGY ....................................................................................... 13 MAKHANA SECTOR ........................................................................................................ 18 CLUSTER MAPPING.................................................................................................... 19 CLUSTER DIAGRAM ...................................................................................................... -

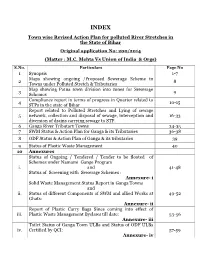

Town Wise Revised Action Plan for Polluted River Stretches in the State of Bihar Original Application No: 200/2014 (Matter : M.C

INDEX Town wise Revised Action Plan for polluted River Stretches in the State of Bihar Original application No: 200/2014 (Matter : M.C. Mehta Vs Union of India & Orgs) S.No. Particulars Page No 1 Synopsis 1-7 Maps showing ongoing /Proposed Sewerage Scheme in 2 8 Towns under Polluted Stretch & Tributaries Map showing Patna town division into zones for Sewerage 3 9 Schemes Compliance report in terms of progress in Quarter related to 4 10-15 STPs in the state of Bihar Report related to Polluted Stretches and Lying of sewage 5 network, collection and disposal of sewage, interception and 16-33 diversion of drains carrying sewage to STP. 6 Ganga River Tributary Towns 34-35 7 SWM Status & Action Plan for Ganga & its Tributaries 36-38 8 ODF Status & Action Plan of Ganga & its tributaries 39 9 Status of Plastic Waste Management 40 10 Annexures Status of Ongoing / Tendered / Tender to be floated of Schemes under Namami Gange Program i. and 41-48 Status of Screening with Sewerage Schemes : Annexure- i Solid Waste Management Status Report in Ganga Towns and ii. Status of different Components of SWM and allied Works at 49-52 Ghats: Annexure- ii Report of Plastic Carry Bags Since coming into effect of iii. Plastic Waste Management Byelaws till date: 53-56 Annexure- iii Toilet Status of Ganga Town ULBs and Status of ODF ULBs iv. Certified by QCI: 57-59 Annexure- iv 60-68 and 69 11 Status on Utilization of treated sewage (Column- 1) 12 Flood Plain regulation 69 (Column-2) 13 E Flow in river Ganga & tributaries 70 (Column-4) 14 Assessment of E Flow 70 (Column-5) 70 (Column- 3) 15 Adopting good irrigation practices to Conserve water and 71-76 16 Details of Inundated area along Ganga river with Maps 77-90 17 Rain water harvesting system in river Ganga & tributaries 91-96 18 Letter related to regulation of Ground water 97 Compliance report to the prohibit dumping of bio-medical 19 98-99 waste Securing compliance to ensuring that water quality at every 20 100 (Column- 5) point meets the standards. -

Arwal District, Bihar State

भूजल सूचना पुस्तिका अरवल जिला, बिहार Ground Water Information Booklet Arwal District, Bihar State के न्द्रीय भमू िजल बो셍 ड Central Ground Water Board Ministry of Water Resources जल संसाधन िंत्रालय (Govt. of India) (भारत सरकार) Mid-Eastern Region म鵍य-पवू ी क्षेत्र Patna पटना ससतंिर 2013 September 2013 Prepared By:- Shri D.G.Dastidar, Scientist-C ARWAL DISTRICT AT A GLANCE Sl. Statistics No. 1. GENERAL INFORMATION I Geographical Area (Sq. Km.) 637 II Administrative Divisions 1 (Arwal) No. of Panchayats/Villages 65/335 Number of Tehsil/Block 5 III Population (As per 2011 Census) Total: 700843 Rural: 648994 Urban: 51849 IV Average Annual Rainfall (mm) 1028 2 GEOMORPHOLOGY Major Physiographic Units 1. Flat Indo-Gangetic Alluvium Tract Major Drainages Sone, Punpun 3 LAND USE i) Forest Area Nil ii) Net Area Sown 361.98 sq.km iii) Total Cropped Area 452.47 sq. km 4 MAJOR SOIL TYPES Inceptisols, Entisols 5 PRINCIPAL CROPS Wheat, Maize, Paddy 6 IRRIGATION BY DIFFERENT SOURCES (Area in hectares) 4 Dugwells - Tubewells/Borewells (STW) 22000 Tanks/ponds Nil Canals 18000 Other Sources 6000 Net Irrigated Area 35000 Gross Irrigated Area 46000 7 NUMBER OF GROUND WATER MONITERING WELLS OF CGWB (2011) No. of Dug wells 06 No. of Piezometers Nil 8 PREDOMINANT GEOLOGICAL Alluvium FORMATIONS 9 HYDROGEOLOGY Major water bearing formations Alluvium Pre-monsoon Depth to water level during 2011 4.58 – 9.8 m bgl Post-monsoon Depth to water level during 2011 2 – 4.6 m bgl Long term water level trend in last 10 yrs(2002 – No significant decline 2011) in m/yr 10 GROUND WATER EXPLORATION BY CGWB (As on 31-03-2013) No.