U-Th Dated Speleothem Recorded Geomagnetic Excursions in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grade 11 Informational Mini-Assessment Stalagmite Trio This Grade 11 Mini-Assessment Is Based on Two Texts and an Accompanying Video About Cave Formations

Grade 11 Informational Mini-Assessment Stalagmite Trio This grade 11 mini-assessment is based on two texts and an accompanying video about cave formations. The subject matter, as well as the stimuli, allow for the testing of the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) for Literacy in Science and Technical Subjects and the Reading Standards for Informational Texts. The texts are worthy of students’ time to read, and the video adds a multimedia component to make the task a more complete and authentic representation of research. The texts meet the expectations for text complexity at grade 11. Assessments aligned to the CCSS will employ quality, complex texts such as these, and some assessments will include multimedia stimuli as demonstrated by this mini-assessment. Questions aligned to the CCSS should be worthy of students’ time to answer and therefore do not focus on minor points of the texts. Several standards may be addressed within the same question because complex texts tend to yield rich assessment questions that call for deep analysis. In this mini-assessment there are twelve questions that address the Reading Standards below. There is also one constructed response item that addresses Reading, Writing, and Language standards. We encourage educators to give students the time that they need to read closely and write to sources. Please note that this mini- assessment is likely to take at least two class periods. Note for teachers of English Language Learners (ELLs): This assessment is designed to measure students’ ability to read and write in English. Therefore, educators will not see the level of scaffolding typically used in instructional materials to support ELLs—these would interfere with the ability to understand their mastery of these skills. -

Introduction to Virginia's Karst

Introduction to Virginia’s Karst A presentation of The Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation’s Karst Program & Project Underground Karst - A landscape developed in limestone, dolomite, marble, or other soluble rocks and characterized by subsurface drainage systems, sinking or losing streams, sinkholes, springs, and caves. Cross-section diagram by David Culver, American University. Karst topography covers much of the Valley and Ridge Province in the western third of the state. Aerial photo of karst landscape in Russell County. Smaller karst areas also occur in the Cumberland Plateau, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain provinces. At least 29 counties support karst terrane in western Virginia. In western Virginia, karst occurs along slopes and in valleys between mountain ridges. There are few surface streams in these limestone valleys as runoff from mountain slopes disappears into the subsurface upon contact with the karst bedrock. Water flows underground, emerging at springs on the valley floor. Thin soils over fractured, cavernous limestone allow precipitation to enter the subsurface directly and rapidly, with a minimal amount of natural filtration. The purer the limestone, the less soil develops on the bedrock, leaving bare pinnacles exposed at the ground surface. Rock pinnacles may also occur where land use practices result in massive soil loss. Precipitation mixing with carbon dioxide becomes acidic as it passes through soil. Through geologic time slightly acidic water dissolves and enlarges the bedrock fractures, forming caves and other voids in the bedrock. Water follows the path of least resistance, so it moves through voids in rock layers, fractures, and boundaries between soluble and insoluble bedrock. -

Speleothem Evidence from Oman for Continental Pluvial Events During Interglacial Periods

Speleothem evidence from Oman for continental pluvial events during interglacial periods Stephen J. Burns Dominik Fleitmann Albert Matter Institute of Geology, University of Bern, CH-3012 Bern, Switzerland Ulrich Neff Augusto Mangini Heidelberg Academy of Sciences, D-69120 Heidelberg, Germany ABSTRACT Growth periods and stable isotope analyses of speleothems from Hoti Cave in northern Oman provide a record of continental pluvial periods extending back over the past four of Earth's glacial-interglacial cycles. Rapid speleothem growth occurred during the early to middle Holocene (6±10.5 ka B.P.), 78±82 ka B.P., 120±135 ka B.P., 180±200 ka B.P., and 300±325 ka B.P. The speleothem calcite deposited during each of these episodes is highly depleted in 18O compared to modern speleothems. The d18O values for calcite deposited within pluvial periods generally fall in the range of 24½ to 28½ relative to the Vienna Peedee belemnite standard, whereas modern speleothems range from 21½ to 23½. The growth and isotopic records indicate that during peak interglacial periods, the limit of the monsoon rainfall was shifted far north of its present location and each pluvial period was coincident with an interglacial stage of the marine oxygen isotope record. The association of continental pluvial periods with peak interglacial conditions suggests that glacial boundary conditions, and not changes in solar radiation, are the primary control on continental wetness on glacial-interglacial time scales. Keywords: speleothems, stable isotopes, Oman, monsoon, uranium-series method. INTRODUCTION rine and continental records show that its in- such as the extent of glaciation on the Hima- How climate in Earth's tropical regions var- tensity has varied considerably in the recent layan plateau or sea-surface temperatures? ied over the course of Earth's glacial-intergla- past. -

Novel Bacterial Diversity in an Anchialine Blue Hole On

NOVEL BACTERIAL DIVERSITY IN AN ANCHIALINE BLUE HOLE ON ABACO ISLAND, BAHAMAS A Thesis by BRETT CHRISTOPHER GONZALEZ Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE December 2010 Major Subject: Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences NOVEL BACTERIAL DIVERSITY IN AN ANCHIALINE BLUE HOLE ON ABACO ISLAND, BAHAMAS A Thesis by BRETT CHRISTOPHER GONZALEZ Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Approved by: Chair of Committee, Thomas Iliffe Committee Members, Robin Brinkmeyer Daniel Thornton Head of Department, Thomas Lacher, Jr. December 2010 Major Subject: Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences iii ABSTRACT Novel Bacterial Diversity in an Anchialine Blue Hole on Abaco Island, Bahamas. (December 2010) Brett Christopher Gonzalez, B.S., Texas A&M University at Galveston Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Thomas Iliffe Anchialine blue holes found in the interior of the Bahama Islands have distinct fresh and salt water layers, with vertical mixing, and dysoxic to anoxic conditions below the halocline. Scientific cave diving exploration and microbiological investigations of Cherokee Road Extension Blue Hole on Abaco Island have provided detailed information about the water chemistry of the vertically stratified water column. Hydrologic parameters measured suggest that circulation of seawater is occurring deep within the platform. Dense microbial assemblages which occurred as mats on the cave walls below the halocline were investigated through construction of 16S rRNA clone libraries, finding representatives across several bacterial lineages including Chlorobium and OP8. -

Speleothem Paleoclimatology for the Caribbean, Central America, and North America

quaternary Review Speleothem Paleoclimatology for the Caribbean, Central America, and North America Jessica L. Oster 1,* , Sophie F. Warken 2,3 , Natasha Sekhon 4, Monica M. Arienzo 5 and Matthew Lachniet 6 1 Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37240, USA 2 Department of Geosciences, University of Heidelberg, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany; [email protected] 3 Institute of Environmental Physics, University of Heidelberg, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany 4 Department of Geological Sciences, Jackson School of Geosciences, University of Texas, Austin, TX 78712, USA; [email protected] 5 Desert Research Institute, Reno, NV 89512, USA; [email protected] 6 Department of Geoscience, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, NV 89154, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 27 December 2018; Accepted: 21 January 2019; Published: 28 January 2019 Abstract: Speleothem oxygen isotope records from the Caribbean, Central, and North America reveal climatic controls that include orbital variation, deglacial forcing related to ocean circulation and ice sheet retreat, and the influence of local and remote sea surface temperature variations. Here, we review these records and the global climate teleconnections they suggest following the recent publication of the Speleothem Isotopes Synthesis and Analysis (SISAL) database. We find that low-latitude records generally reflect changes in precipitation, whereas higher latitude records are sensitive to temperature and moisture source variability. Tropical records suggest precipitation variability is forced by orbital precession and North Atlantic Ocean circulation driven changes in atmospheric convection on long timescales, and tropical sea surface temperature variations on short timescales. On millennial timescales, precipitation seasonality in southwestern North America is related to North Atlantic climate variability. -

Museum of Natural History & Science Interpretation Guide for the Cavern

Museum of Natural History & Science Interpretation Guide for The Cavern A cave is a naturally occurring hole in the ground large enough to be explored by humans. Caves can be found on every continent in the world. Caves, along with the objects found within them, are extremely fragile and take millions of years to form. They are home to unique organisms—many of which are still unknown to science; they are archaeological sites that preserve our cultural heritage; and geologic laboratories that demonstrate how water can both dissolve and deposit rock. Caves are a vital and non-renewable resource that must be conserved and protected. The Cavern is a recreation of a Kentucky limestone dissolution cave. It is the largest artificial cave in the United States—and some say the world—containing 535 feet of passage in an area 44 feet wide, 24 feet high and 64 feet long. Parts of the cave were modeled after two caves in Kentucky: Teamers Cave in Rockcastle County and Dyches Bridge Cave in Pulaski County. By modeling our cavern after these two caves, our dissolution cave has a realistic appearance. A dissolution cave is by far the most common type of cave. They can be found throughout the world if the right conditions present themselves. The formation of a dissolution cave requires four basic elements: rock, water, carbon dioxide and time. • Rock, especially carbonate rocks, such as limestone, is the first ingredient. These types of rocks were formed hundreds of millions of years ago. It is in the seas surrounding the continents that limestone is formed. -

Caves of Missouri

CAVES OF MISSOURI J HARLEN BRETZ Vol. XXXIX, Second Series E P LU M R I U BU N S U 1956 STATE OF MISSOURI Department of Business and Administration Division of GEOLOGICAL SURVEY AND WATER RESOURCES T. R. B, State Geologist Rolla, Missouri vii CONTENT Page Abstract 1 Introduction 1 Acknowledgments 5 Origin of Missouri's caves 6 Cave patterns 13 Solutional features 14 Phreatic solutional features 15 Vadose solutional features 17 Topographic relations of caves 23 Cave "formations" 28 Deposits made in air 30 Deposits made at air-water contact 34 Deposits made under water 36 Rate of growth of cave formations 37 Missouri caves with provision for visitors 39 Alley Spring and Cave 40 Big Spring and Cave 41 Bluff Dwellers' Cave 44 Bridal Cave 49 Cameron Cave 55 Cathedral Cave 62 Cave Spring Onyx Caverns 72 Cherokee Cave 74 Crystal Cave 81 Crystal Caverns 89 Doling City Park Cave 94 Fairy Cave 96 Fantastic Caverns 104 Fisher Cave 111 Hahatonka, caves in the vicinity of 123 River Cave 124 Counterfeiters' Cave 128 Robbers' Cave 128 Island Cave 130 Honey Branch Cave 133 Inca Cave 135 Jacob's Cave 139 Keener Cave 147 Mark Twain Cave 151 Marvel Cave 157 Meramec Caverns 166 Mount Shira Cave 185 Mushroom Cave 189 Old Spanish Cave 191 Onondaga Cave 197 Ozark Caverns 212 Ozark Wonder Cave 217 Pike's Peak Cave 222 Roaring River Spring and Cave 229 Round Spring Cavern 232 Sequiota Spring and Cave 248 viii Table of Contents Smittle Cave 250 Stark Caverns 256 Truitt's Cave 261 Wonder Cave 270 Undeveloped and wild caves of Missouri 275 Barry County 275 Ash Cave -

Some Unintended Results of Blanket Cave Closures: a Story About Fern Cave Jennifer Pinkley

Some Unintended Results of Blanket Cave Closures: a Story about Fern Cave Jennifer Pinkley The first time I visited Alabama’s Fern Along the way, explorers found beauti- Grotto members about gray bats and the Cave, I thought of the Mines of Moria in ful and rare helictites, gypsum crystals that need to avoid disturbing them. The Grotto JRR Tolkien’s Middle Earth: vast beyond look like giant corn flakes, huge dogtooth started to get the word out that cavers should imagining. As I moved through the cave, it spar calcite formations, rimstone dams, stay out of the approximately three miles of seemed that around every corner I discovered towering flowstone, giant rooms, deep pits, Morgue passage of the cave in the winter. another passage, another canyon, another cave pearls, and stream passage. In obscure Cavers complied. The bats thrived. path to explore. On that first bewildering rooms, cavers found bones of extinct animals trip, I visited Helictite Heaven, one of the that roamed the earth over 13,000 years MAnAgeMent under tHe us FisH And most beautiful and bizarre rooms not only in ago, including giant-sized varieties of cave WiLdLiFe serviCe Fern, but in any cave I’ve ever visited. Weird bears, armadillos, and lions. Hidden in the In 1980, the US Fish and Wildlife rock forms sprout out of the floors, walls and mud were also jaguar teeth, a horse tooth, Service (FWS) purchased all of the entrances ceilings like mutant, sparkling coral bushes. and a 2,400-year-old human jawbone. to Fern, except Surprise Pit, to protect the After that trip, I was hooked. -

The Use of ASH-15 Flowstone As a Matrix-Matched Reference Material for Laser-Ablation

https://doi.org/10.5194/gchron-2020-22 Preprint. Discussion started: 27 July 2020 c Author(s) 2020. CC BY 4.0 License. 1 The use of ASH-15 flowstone as a matrix-matched reference material for laser-ablation 2 U-Pb geochronology of calcite 3 Perach Nuriel1, Jörn-Frederik Wotzlaw2, Maria Ovtcharova3, Anton Vaks1, Ciprian Stremtan4, 4 Martin Šala5, Nick M. W. Roberts6, and Andrew R. C. Kylander-Clark7 5 6 1 Geological Survey of Israel, 32 Yeshayahu Leibowitz St. Jerusalem, 9692100, Israel 7 2 Institute of Geochemistry and Petrology, ETH Zurich, Clausiusstrasse 25 I CH-8092 Zurich, 8 Switzerland 9 3 Department of Earth Sciences, University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland 10 4 Teledyne Photon Machines, 384 Gallatin Park Drive, Bozeman, MT 59715, USA 11 5 Department of Analytical Chemistry, National Institute of Chemistry, Hajdrihova 19, SI- 12 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia. 13 6 Geochronology and Tracers Facility, British Geological Survey, Environmental Science 14 Centre, Nottingham, NG12 5GG, UK 15 7 Department of Earth Science, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA 93106, USA. 16 17 Abstract 18 Latest advances in laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (LA-ICPMS) 19 allow for accurate in-situ U-Pb dating of carbonate material, with final age uncertainties 20 usually >3% 2σ. Cross-laboratory reference materials (RMs) used for sample-bracketing are 21 currently limited to WC1 calcite with an age of 254.4 ± 6.5 (2σ). The minimum uncertainty 22 on any age determination with the LA-ICPMS method is therefore ≥ 2.5%, and validation by 23 secondary RMs are usually performed on in-house standards. -

A High-Resolution Late Holocene Speleothem Record from Kaite Cave, Northern Spain: 8180 Variability and Possible Causes

A high-resolution late Holocene speleothem record from Kaite Cave, northern Spain: 8180 variability and possible causes b b David Dominguez-Villara,*, Xianfeng Wang , Hai Cheng , b Javier Martin-ChiveletC, R. Lawrence Edwards a Departamento de Geodincimica, Fac. cc. Geoidgicas, Universidad Complutense, 28040 Madrid, Spain b Department of' Geolo!}y and Geophysics, University of Minnesota, Minneapo/is, MN 55455, USA CDepartamento de Estratigraji:a, Inst. de Geoloyia Economiea (CSIC-UCM), Fae. Cc. Geologicas, Universidad Complutense, 28040 Madrid, Spain Abstract 18 A high-resolution calcite oxygen stable isotopic (0 0) record, covering the past 4000 years, was obtained from Kaite Cave, northern 18 18 Spain. The record has a mean 0 0 value of -6.25%0 VPDB and a range of 2%0. Spectral analysis of the 0 0 data shows significant periodicities of 2400-1900,600, 150,27, and 22 years. The amplitudes during these periods range from 0.2%0 to 2%0. Factors controlling the isotopic ratio in the speleothem were evaluated. The calcite is most likely precipitated under equilibrium conditions, with the cave 18 calcite 0 0 interpreted as a proxy of oxygen isotopic composition in local rainwater. Other factors such as temperature or fractionation in the karst system prior to calcite precipitation are considered of negligible or of minor importance. Mechanisms affecting rainfall isotopic composition were also investigated on different time scales. Precipitation amount is the primary factor controlling the high 18 frequency 0 0 oscillations. Other climate parameters, such as changes of storm tracks may have significant contributions on centennial and millennial time scales. -

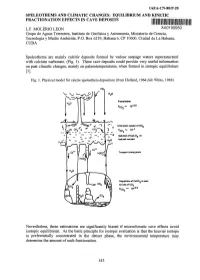

Iaea-Cn-80/P-20 Speleothems and Climatic Changes: Equilibrium and Kinetic Fractionation Effects in Cave Deposits

IAEA-CN-80/P-20 SPELEOTHEMS AND CLIMATIC CHANGES: EQUILIBRIUM AND KINETIC FRACTIONATION EFFECTS IN CAVE DEPOSITS L.F. MOLERIO LEON XA0100950 Grupo de Aguas Terrestres, Instituto de Geofisica y Astronomia, Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnologia y Medio Ambiente, P.O. Box 6219, Habana 6, CP 10600, Ciudad de La Habana, CUBA Speleothems are mainly calcitic deposits formed by vadose seepage waters supersaturated with calcium carbonate. (Fig. 1). These cave deposits could provide very useful information on past climatic changes, mainly on palaeotemperatures, when formed in isotopic equilibrium [1]. Fig. 1. Physical model for calcite speleothem deposition (from Holland, 1964 fide White, 1988) CO, Precipitation H2O Infiltration uptake of COj 2 B ~"J~ Solution of CaC O3 at bedrock contact Transport along joints Deposition of CaCO-j in cave by loss of CO2 Nevertheless, these estimations are significantly biased if microclimatic cave effects avoid isotopic equilibrium. As the basic principle for isotopic evaluation is that the heavier isotope is preferentially concentrated in the denser phase, the environmental temperature may determine the amount of such fractionation. 143 IAEA-CN-80/P-20 Two effects can therefore, alter the isotopic equilibrium, v.gr. the most ideal condition for palaeoenvironmental assessments. These effects are evaporation and outgassing of CO2 from vadose seepage. They produce the so-called kinetic fractionation. Kinetic fractionation is often associated to the microclimatic cave environment, the pending time of solution on the roof of the cave, the speleothem surface and the flow of stalagmite and flowstone [1,2]. As these factors exert a remarkable influence on the genesis of speleothems, an association between kinetic fractionation and speleothem type is recognized. -

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Wind Cave National Park

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Wind Cave National Park Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR—2009/087 THIS PAGE: Calcite Rafts record former water levels at the Deep End a remote pool discovered in January 2009. ON THE COVER: On the Candlelight Tour Route in Wind Cave boxwork protrudes from the ceiling in the Council Chamber. NPS Photos: cover photo by Dan Austin, inside photo by Even Blackstock Wind Cave National Park Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR—2009/087 Geologic Resources Division Natural Resource Program Center P.O. Box 25287 Denver, Colorado 80225 March 2009 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Denver, Colorado The Natural Resource Publication series addresses natural resource topics that are of interest and applicability to a broad readership in the National Park Service and to others in the management of natural resources, including the scientific community, the public, and the NPS conservation and environmental constituencies. Manuscripts are peer-reviewed to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and is designed and published in a professional manner. Natural Resource Reports are the designated medium for disseminating high priority, current natural resource management information with managerial application. The series targets a general, diverse audience, and may contain NPS policy considerations or address sensitive issues of management applicability. Examples of the diverse array of reports published in this series include vital signs monitoring plans; "how to" resource management papers; proceedings of resource management workshops or conferences; annual reports of resource programs or divisions of the Natural Resource Program Center; resource action plans; fact sheets; and regularly-published newsletters.