Purbeck-Seabirds-Survey-2018.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5-Night Dorset Coast Christmas & New Year Guided

5-Night Dorset Coast Christmas & New Year Guided Walking Holiday Tour Style: Guided Walking Destinations: Dorset Coast & England Trip code: LHXFW-5 2 & 3 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW The Dorset Coast is beautiful all year round but there are some even more spectacular sights around winter. Spend the festive season on the Dorset Coast, socialising and walking in this beautiful place. There’s something magical about walking in winter. Whether it’s the frosty footsteps, the clear crisp air, or the breathtaking views, it’s a wonderful time to go walking. Join our festive breaks and choose from a guided walking holiday in the company of one of our knowledgeable leaders. We pull out all the stops on our festive holidays, with fabulous food, lots of seasonal entertainment and great walks and activities. The walks are tailored to the time of year and will remain flexible to suit the weather conditions. Each day three grades of walk will be offered. So wrap up warm, lace up your boots and go for an invigorating walk. WHAT'S INCLUDED • Wonderful meals – full selection at breakfast, your choice of picnic lunch, an excellent evening meal and plenty of festive treats • A programme of organised walks and activities www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 • The services of experienced HF Holidays’ guides • A packed programme of evening activities offering something festive for everyone, including some old HF favourites • Any transport to and from the walks HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Enjoy Christmas or New Year at our new Country House at Lulworth Cove • Plenty of exercise to walk off the festive excesses • A choice of guided walks along the spectacular Dorset Coast • Just relax, soak up the party atmosphere, enjoy wonderful festive fare and leave all the organising to us • Evening activities include dancing, quizzes and carol evenings TRIP SUITABILITY The walks are tailored to the time of year and will remain flexible to suit the weather conditions. -

South West Coast Path : Weymouth to Lulworth Cove Walk

Saturday Walkers Club www.walkingclub.org.uk South West Coast Path : Weymouth to Lulworth Cove walk Weymouth Bay, then a dramatic cliff walk past small beaches, then higher cliffs past Durdle Door (stack) to Lulworth Cove Length 11.1 miles / 17.8 km Toughness 8 out of 10 - 2,400 feet / 730m of ascent (lots of small climbs) Features This spectacular coast walk follows the waymarked South West Coastal Path (SWCP) / England Coast Path (ECP) from Weymouth (seaside town with picturesque harbour) along its seafront promenade, then over spectacular cliffs and past secluded coves and beaches towards Durdle Door (stack) and Lulworth Cove. All, with views over Weymouth Bay and the Isle of Portland. The start is gentle - along the seafront then seawall. Then over a small hill (pub, cafe, both with sea views) to Bowleaze Cove with its spectacular art deco hotel. Then past some small beaches to the Smugglers Inn in Osmington for lunch. After lunch the cliff top path continues on past Ringstead and above Burning Cliff beach (the fire went out in in 19th C). It passes St Catherine-by- the-Sea church (nice picnic spot), and then becomes an undulating cliff edge walk (a more level inland option is available) to Durdle Door (a stack, great beach) before descending to Lulworth Cove. Return to Wool Station by bus (summer only) or taxi This walk can also be done in reverse, indeed transport considerations may may that a better option. In this case, take a bus from Wool to Lulworth Cove. At the end, continue along the coast to Weymouth's Historic Harbour area which is much nicer than the tacky seafront next to the train station https://www.walkingclub.org.uk/walk/weymouth-to-lulworth-cove/ 1/6 You hardly need a map for this walk as the SWCP is very well waymarked, and you are just following the coast, but it is useful to check your progress. -

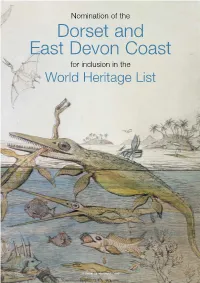

Dorset and East Devon Coast for Inclusion in the World Heritage List

Nomination of the Dorset and East Devon Coast for inclusion in the World Heritage List © Dorset County Council 2000 Dorset County Council, Devon County Council and the Dorset Coast Forum June 2000 Published by Dorset County Council on behalf of Dorset County Council, Devon County Council and the Dorset Coast Forum. Publication of this nomination has been supported by English Nature and the Countryside Agency, and has been advised by the Joint Nature Conservation Committee and the British Geological Survey. Maps reproduced from Ordnance Survey maps with the permission of the Controller of HMSO. © Crown Copyright. All rights reserved. Licence Number: LA 076 570. Maps and diagrams reproduced/derived from British Geological Survey material with the permission of the British Geological Survey. © NERC. All rights reserved. Permit Number: IPR/4-2. Design and production by Sillson Communications +44 (0)1929 552233. Cover: Duria antiquior (A more ancient Dorset) by Henry De la Beche, c. 1830. The first published reconstruction of a past environment, based on the Lower Jurassic rocks and fossils of the Dorset and East Devon Coast. © Dorset County Council 2000 In April 1999 the Government announced that the Dorset and East Devon Coast would be one of the twenty-five cultural and natural sites to be included on the United Kingdom’s new Tentative List of sites for future nomination for World Heritage status. Eighteen sites from the United Kingdom and its Overseas Territories have already been inscribed on the World Heritage List, although only two other natural sites within the UK, St Kilda and the Giant’s Causeway, have been granted this status to date. -

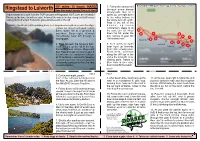

Ringstead to Lulworth Cove.Cdr

1 1 Download the FREE Sports Tracker app, to keep a log of your activities 10 / 2 miles : 4 /2 hours : HARD 7. Follow the narrow trail Ringstead to Lulworth Notes: Steep climbs & descents! Close to cliff edges! through some dense undergrowth, then as it I have started this walk from the TOP car park at Ringstead, NOT down at the beach! opens up, turn right down Driving up the lane, do not turn right, follow all the way to the top, along the flat & over a to the valley bottom. In cattle grid into the field. Follow the gravel track & park on the left. the valley, turn left, uphill. Pass to the left of the 1. Walk to the far end of the parking area, to a large wooden gate & go over the style. h o u s e , u p s o m e Follow the gravel track past Falcon rudimentary steps & at Barn, down hill to a junction & the road, turn left. Head 1 p o s t b o x . B e a r r i g h t . A l m o s t down the hill, under the 2 13 12 immediately, bear left through a tree canopy & past the Obelisk 11 10 kissing gate. "millionaires row". 4 White Nothe 3 9 5 6 2. Pass between the house & barn, 8. As it opens up again Bat's Head 7 8 head straight up the hill to the top. bear right up towards Durdle Door Stair Hole Fantastic views across Weymouth Stair Hole viewing point. -

Upper Cretaceous” Deposits Are Part of the Noachian Flood

Answers Research Journal 2 (2009): 29–51. www.answersingenesis.org/arj/v2/chalk-upper-cretaceous.pdf Chalk and “Upper Cretaceous” Deposits are Part of the Noachian Flood John D Matthews, Lampton Close, Wool, Dorset, BH20 6EW, UK Abstract Thick chalk deposits exist in several parts of the world, including Europe, Australia and the USA. The bulk of this chalk is considered to belong to what is referred to as the “Upper Cretaceous” period. Geologists working within a framework of uniformitarianism (or actualism) claim that they result from millions of years of accumulation of coccoliths. If we are to take the new understanding of the age of the earth from RATE studies seriously, then it is necessary to explain the chalk by mechanisms which do not involve such long timescales. Snelling (1994) attempted to explain the chalk deposits within a timescale of a few days, so that chalk could be considered as part of the visible evidence for the Noachian Flood. Tyler (1996) then tried to show that the model proposed by Snelling was not tenable, and described how chalk had to be interpreted as a post-Flood deposit, but within a short timescale. This document shows two things. First, that the certain features of the “Upper Cretaceous” period correspond closely with the biblical account of the Noachian Flood around day 150. Second, that uniformitarian explanations for “chalk” are inadequate to explain their deposition, reworking and geomorphology and that only by considering the rapid events in the middle of the Noachian Flood can their deposition and characteristics be explained. En passant we make two additional discoveries, viz (i) that the concept of the geological column is not robust over small distances, and (ii) that there is independent support to the RATE studies that show that the earth is young. -

The Geology Durdle Door, Dorset Chalk Stratigraphy, Sedimentology and Tectonic Structure New Marker Beds

Wessex OUGS Field Guide to Durdle Door, Dorset, May 2018 The Geology Durdle Door, Dorset Chalk stratigraphy, sedimentology and tectonic structure New marker beds Durdle Cove, Dorset looking west over Scratchy Bottom and Swyre Head to Bat’s Head. The line of caves at the foot of the cliff in Durdle Cove is formed on the Durdle Cove Thrust (see also Rowe 1901, Plate III, pp. 16-17). Open University Geological Society Wessex Group Field Excursion Sunday 13th May 2018 Leaders: Rory Mortimore and Jeremy Cranmer Field guide prepared by Rory Mortimore www.chalkrock.com Based on the paper Late Cretaceous stratigraphy, sediments and structure: gems of the Jurassic Coast of Devon and Dorset, England just going into press in the Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, 2018. 1 Wessex OUGS Field Guide to Durdle Door, Dorset, May 2018 Wessex OUGS Field Trip Durdle Door, Durdle Cove, Scratchy Bottom and Bat’s Head Late Cretaceous stratigraphy, sediments and structure: gems of the Jurassic Coast of Devon and Dorset, England Introduction Extraordinary, long-distance litho-marker beds such as the Lewes and Shoreham Tubular Flints and associated marl seams and fossils (Fig.2), recognised in cliff exposures and cliff-fall boulders, are keys to unlocking the stratigraphy and tectonic structures in the Late Cretaceous (Fig.1) of the Jurassic Heritage Coast. Durdle Cove is a special gem exposing the Lewes and Seaford Chalk stratigraphy where these and new marker beds are identified and where sediments and tectonic structures provide clues to timing of movements that produced a Late Cretaceous pericline which grew into a Miocene monocline along the line of the underlying Purbeck Reverse Fault. -

4-Night Dorset Coast Guided Walking for Solos Holiday

4-Night Dorset Coast Guided Walking for Solos Holiday Tour Style: Guided Walking Holidays for Solos Destinations: Dorset Coast & England Trip code: LHBOS-4 2 & 3 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW In the heart of the Jurassic Coast, snuggled above the shimmering waters of Lulworth Cove, our newly refurbished Country House is the perfect base for exploring this glorious fossil-rich coastline. On our Guided Walking holidays you'll visit beaches, lofty cliffs and the iconic arch of Durdle Door. WHAT'S INCLUDED • High quality en-suite accommodation in our country house • Full board from dinner upon arrival to breakfast on departure day • 3 days guided walking • Use of our comprehensive Discovery Point • Choice of up to three guided walks each walking day • The services of HF Holidays Walking Leaders www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Enjoy the remarkable coastal path and views of the iconic chalk cliffs, rugged headlands and hidden bays • Soak up the sea air and delight in the sweeping panoramas over the rolling Dorset hills • Let our knowledgeable leaders bring the surroundings to life • Spend the evenings enjoying the spectacular views from the terrace and outdoor swimming pool ITINERARY Day 1: Arrival Day You're welcome to check in from 4pm onwards. Enjoy a complimentary Afternoon Tea on arrival. Day 2: Corfe Castle To Studland Option 1 - Corfe Castle To Studland Distance: 7 miles (11km) Ascent: 1,050 feet (320m) In Summary: Enjoy a stunning variety of inland and coastal scenery. Our walk from Corfe Castle to Studland follows the glorious chalk ridge along the spine of Purbeck peninsula, with the views getting ever more impressive as we near our destination. -

7-Night Dorset Coast Guided Walking Holiday

7-Night Dorset Coast Guided Walking Holiday Tour Style: Guided Walking Destinations: Dorset Coast & England Trip code: LHBOB-7 2 & 3 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW In the heart of the Jurassic Coast, snuggled above the shimmering waters of Lulworth Cove, our newly refurbished Country House is the perfect base for exploring this glorious fossil-rich coastline. On our Guided Walking holidays you'll visit beaches, lofty cliffs and the iconic arch of Durdle Door. WHAT'S INCLUDED • High quality en-suite accommodation in our country house • Full board from dinner upon arrival to breakfast on departure day • 5 days guided walking and 1 free day • Use of our comprehensive Discovery Point • Choice of up to three guided walks each walking day • The services of HF Holidays Walking Leaders www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Enjoy the remarkable coastal path and views of the iconic chalk cliffs, rugged headlands and hidden bays • Soak up the sea air and delight in the sweeping panoramas over the rolling Dorset hills • Let our knowledgeable leaders bring the surroundings to life • Spend the evenings enjoying the spectacular views from the terrace and outdoor swimming pool ITINERARY ACCOMMODATION West Lulworth House Set just 200 yards from the sea, West Lulworth House has a highly coveted location just above the lake-still expanse of Lulworth Cove on Dorset’s iconic Jurassic Coast. Built in 1881 by the then Mayor of Weymouth, it has been perennially popular with walkers, twitchers and fossil hunters. As well as 22 delightful bedrooms, there’s a south facing garden and elevated terrace with cracking views, an outdoor heated pool and a pair of lovely lounges, perfect for a relaxing walking holiday exploring the Jurassic Coast. -

The Quaternary Rivers of the Jurassic Coast Region: from the Neogene to the Anthropocene

1 The Quaternary Rivers of the Jurassic Coast Region: from the Neogene to the Anthropocene A. G. Browna, L. S. Basellb, P. S. Tomsc a Geography & Environment, University of Southampton, Southampton SO17 1BJ, UK b Archaeology & Palaeoecology, School of Natural and Built Environment, Queens University, Belfast BT7 1NN, UK c Luminescence dating laboratory, School of Natural and Social Sciences, University of Gloucestershire, Swindon Road, Cheltenham GL50 4AZ UK Abstract The Jurassic Coast World Heritage Sites (JCWHS) is not only a 95 km long coastline and remarkable Mesozoic geological section, but also a slice through a Quaternary landscape. For the majority of the last two million years this landscape lay in the periglacial zone, just south of a waxing and waning ice margin and just north of an Atlantic inlet which eventually became the English Channel. This paper reviews how the previous landscape inherited from the Cenozoic, was modified through uplift, climatically driven fluvial activity and periglaciation. Much evidence of this Quaternary history can be been today in sections along the JCWHS coast which is cuts through a number of headwater valleys the largest of which are the Exe and Axe. Recent studies, largely funded from the Aggregate Levy Tax, have produced the first independent chronologies for the Exe and Axe valleys and a model of how periglaciation interacted with the layer-cake stratigraphy of the Mesozoic bedrocks of the JCWHS. The Quaternary history of the JCWHS is also preserved in raised beaches on the Isle of Portland, coastal landforms, and in Holocene alluvial sediments associated with human activity and which may constitute part of the putative Anthropocene. -

Seabird Breeding Success Survey, for Ballard Cliff (Handfast to Ballard Point), Durlston to St

1.1 Purbeck Seabird Survey 2011 Footprint Ecology/MARINELife Date: 15 November 2011 Version: FINAL Recommended Citation: Lake, S., Liley, D. , Lane, K., Hopper, N. & Brereton, T. (2011) Seabird Breeding Success Survey, for Ballard Cliff (Handfast to Ballard Point), Durlston to St. Aldhelms Head and Gad cliff to White Nothe, South-East Dorset Coast, Dorset. Footprint Ecology/MarineLife/National Trust. Front cover photo: N. Hopper 2 Purbeck Seabird Survey 2011 Footprint Ecology/MARINELife Summary Breeding seabird surveys have been carried out on the Purbeck coast since 1965. Here we present data from the most recent survey carried out in 2011. We compile data from previous surveys and set them in the context of UK trends. Difficulties in carrying out censuses for some species such as guillemots meant that totals should be used with some caution. However, a relatively high level of consistency in monitoring methodology, including dates, between the surveys mean that overall trends are likely to be fairly robust. Seabirds breeding on the Purbeck coast include fulmar, cormorant, shag, herring gull, great black-backed gull, kittiwake, guillemot, razorbill and puffin. None of the populations are large. The guillemot population is the largest at around 650 individuals, and the puffin population the smallest at three-five breeding pairs. There are just over 100 breeding pairs of herring gulls and cormorants. Other species have populations within the ranges of about 30-50, except great black-backed gull which currently has a population of only eight breeding pairs. All species with the exception of shags appear to be currently declining. Cormorants, shags, fulmars, kittiwakes and guillemots all showed a significant increase during the first half of the survey period, but have declined in numbers more recently. -

Wool Circular (Via the Warren and Lulworth Cove and Castle)

Wool Circular (via The Warren, Lulworth Cove & Castle) Wool Circular (w/o The Warren but via Swyre Head) 1st walk check 2nd walk check 3rd walk check 1st walk check 2nd walk check 3rd walk check Current status Document last updated Monday, 25th November 2019 This document and information herein are copyrighted to Saturday Walkers’ Club. If you are interested in printing or displaying any of this material, Saturday Walkers’ Club grants permission to use, copy, and distribute this document delivered from this World Wide Web server with the following conditions: • The document will not be edited or abridged, and the material will be produced exactly as it appears. Modification of the material or use of it for any other purpose is a violation of our copyright and other proprietary rights. • Reproduction of this document is for free distribution and will not be sold. • This permission is granted for a one-time distribution. • All copies, links, or pages of the documents must carry the following copyright notice and this permission notice: Saturday Walkers’ Club, Copyright © 2019, used with permission. All rights reserved. www.walkingclub.org.uk This walk has been checked as noted above, however the publisher cannot accept responsibility for any problems encountered by readers. Wool Circular (via The Warren and Lulworth Cove and Castle) Start & Finish: Wool Station Wool Station, map reference SY 844 869, is 173 km south west of Charing Cross, 15m above sea level and in Dorset. Length: 30.9 km (19.2 mi). Cumulative ascent/descent: 707m. For a shorter or longer walk and an Alternative Start in Winfrith Newburgh or Durdle Door or a Finish at Lulworth Cove, see below Walk options. -

5-Night Dorset Coast Christmas & New Year Guided

5-Night Dorset Coast Christmas & New Year Guided Walking Holiday Tour Style: Guided Walking Destinations: Dorset Coast & England Trip code: LHXFW-5 2 & 3 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW The Dorset Coast is beautiful all year round but there are some even more spectacular sights around winter. Spend the festive season on the Dorset Coast, socialising and walking in this beautiful place. There’s something magical about walking in winter. Whether it’s the frosty footsteps, the clear crisp air, or the breathtaking views, it’s a wonderful time to go walking. Join our festive breaks and choose from a guided walking holiday in the company of one of our knowledgeable leaders. We pull out all the stops on our festive holidays, with fabulous food, lots of seasonal entertainment and great walks and activities. The walks are tailored to the time of year and will remain flexible to suit the weather conditions. Each day three grades of walk will be offered. So wrap up warm, lace up your boots and go for an invigorating walk. WHAT'S INCLUDED • Wonderful meals – full selection at breakfast, your choice of picnic lunch, an excellent evening meal and plenty of festive treats • A programme of organised walks and activities www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 • The services of experienced HF Holidays’ guides • A packed programme of evening activities offering something festive for everyone, including some old HF favourites • Any transport to and from the walks HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Enjoy Christmas or New Year at our new Country House at Lulworth Cove • Plenty of exercise to walk off the festive excesses • A choice of guided walks along the spectacular Dorset Coast • Just relax, soak up the party atmosphere, enjoy wonderful festive fare and leave all the organising to us • Evening activities include dancing, quizzes and carol evenings TRIP SUITABILITY The walks are tailored to the time of year and will remain flexible to suit the weather conditions.