Exploring Issues Within Post-Olympic Games Legacy Governance: the Case of the 2018 Pyeongchang Winter Olympic Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2013 GOC Chart As of August 1St 2012.Xlsx

2013 Games Organizing Committee Chart (As of August 1st, 2012) Chairwoman of 2013 GOC Chief Secretary 5th Na, Kyung Won Choi, Su Young Cho, Sung Jin The National Assembly Contract Employee Contract Employee 4th Officer of Audit & Inspection Secretary Secretary General of 2013 GOC Officer of Games Security 4th 4th 4th Jeon, Choon Mi Kwon, Oh Yeong Park, Hyun Joo Lim, Byoung Soo Kim, Ki Yong Jang, Chun Sik Park, Yoon Soo Lee, Chan Sub Donghae city The Board of Audit & Inspection of Korea Gangwon Province ormer Assistant Deputy Minister of MCS Gangwon Province Gangwon Province GW Police Agency Director General of Planning Bureau Director General of Competition Management Bureau Director General of Games Support Bureau Yi, Ki Jeong Cho, Kyu Seok Ahn, Nae Hyong Ministry of Culture, S & T Gangwon Province Ministry of Strategy & Finance Director of Planning & GA Departmen Director of Int'l Affairs Department Director of Competition Department Director of Facilities Department Director of HR & Supplies Departmen rector of Games Support Departme Jeon, Jae Sup Kim, Gyu Young Lee, Kang Il Lim, Seung Kyu Lee, Gyeong Ho Hong, Jong Yeoul Gangwon Province MOFAT Ministry of PA & Security Gangwon Province Gangwon Province Gangwon Province Manager of Planning Team anager of General Affairs Te Manager of Finance Team Manager of Protocol Team anager of Int'l Relations TeaManager of Immigration Tea anager of Credentialing Tea Manager of General Competitions Team Manager of Competition Support Tea Manager Snow Sports Team Manager of Ice Sports Team Manager -

KNCU – Corée Du Sud : STV 2016

KNCU – Corée du Sud : STV 2016 Sommaire Workcamp Programmes of the Korean National Commission for UNESCO (KNCU) ........................................................ 1 I. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................... 2 II. Workcamp Summary..................................................................................................................................................... 3 III. Workcamp Programmes .............................................................................................................................................. 5 Workcamp Programmes of the Korean National Commission for UNESCO (KNCU) 2016 1 Service Volontaire International, asbl 30, Rue des Capucins – 1000 Bruxelles : +32 (0) 2 888 67 13 : + 33 (0)3 66 72 90 20 : + 41 (0)3 25 11 0731 I. Introduction Name of organization Korean National Commission for UNESCO Date of foundation 30 January 1954 Type Semi-Governmental Activities STV Only Age limit 19-30 Fee No participation or exchange fee Language of camp English for all camps The Korean National Commission for UNESCO (KNCU) was established in 1954, under the Ministry of Education, following the Republic of Korea’s admission to UNESCO in 1950. Since its establishment, KNCU has recognized youth as a driving force for social change and has promoted youth participation in society at the national and international levels in line with UNESCO’s strategy of action with and -

The Olympic & Paralympic Winter Games Pyeongchang 2018 English

English The Olympic&Paralympic Winter Games PyeongChang 2018 Welcome to Olympic Winter Games PyeongChang 2018 PyeongChang 2018! days February PyeongChang 2018 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games will take place in 17 / 9~25 PyeongChang, Gangneung and Jeongseon for 27 days in Korea. Come and watch the disciplines medal events new records, new miracles, and new horizons unfolding in PyeongChang. 15 102 95 countries 2 ,900athletes Soohorang The name ‘Soohorang’ is a combinati- on of several meanings in the Korean language. ‘Sooho’ is the Korean word for ‘protection’, meaning that it protects the athletes, spectators and all participants of the Olympic Games. ‘Rang’ comes from the middle letter of ‘ho-rang-i’, which means ‘tiger’, and also from the last letter of ‘Jeongseon Arirang’, a traditional folk music of Gangwon Province, where the host city is located. Paralympic Winter Games PyeongChang 2018 10 days/ 9~18 March 6 disciplines 80 medal events 45 countries 670 athletes Bandabi The bear is symbolic of strong will and courage. The Asiatic Black Bear is also the symbolic animal of Gangwon Province. In the name ‘Bandabi’, ‘banda’ comes from ‘bandal’ meaning ‘half-moon’, indicating the white crescent on the chest of the Asiatic Black Bear, and ‘bi’ has the meaning of celebrating the Games. VISION PyeongChang 2018 will begin the world’s greatest celebration of winter sports from 9 February 2018 in PyeongChang, Gangneung, New Horizons and Jeongseon. People from all corners of the PyeongChang 2018 will open the new horizons for Asia’s winter sports world will gather in harmony. PyeongChang will and leave a sustainable legacy in PyeongChang and Korea. -

ICLEI East Asia Secretariat Annual Report 2014

ICLEI East Asia Secretariat Annual Report 2014 www.eastasia.iclei.org CONTENT GREETINGS P.1-2 PROFILE p.3 GOVERNANCE p.4 STRATEGIC DEVELOPMENT p.5-6 PROGRAMS & PROJECTS p.7-8 CAPACITY BUILDING p.9-10 OUR STAFF p.11-13 GREETINGS From the Founding Director East Asia continues to be the world’s most thriving region. ICLEI is proud to have enlarged its presence and capacity to support East Asian cities in their sustainability efforts and to engage them in our programs. The ICLEI East Asia Secretariat has launched two programs this past year. The Energy-safe Cities East Asia program works with three cities each from China, Japan and South Korea and one Mongolian city to explore with which currently available technologies and at what costs the cities could transform their urban energy systems to become low-carbon, low-risk and resilient – practically 100% renewable – by the year 2030. True, it is an ambitious approach, but how can we make a difference if we are not ambitious? After one and a half year of preparations we have launched the program with a first experts symposium held in Beijing in October 2014. As a precursor of a Green Public Procurement program for Chinese cities we have organized EcoProcura© China 2014, an international symposium in Beijing that brought experts from the Chinese government, international organizations, Chinese as well as foreign cities together for an exchange of information, practices and experiences. We have been present at key events in China and spurred attention to resilience in urban planning and management and brisked up the discussion on car-centered urban development by calling for EcoMobility-oriented planning. -

February 2018 Vol

News We’re All a Part Of . February 2018 Vol. 7 Issue 4 Observer Contents 2 Vol. 7 Issue 4 February 2018 Letter from the Staff Contents Mission & Vision Dear Readers, Cover: Designed by Josh C. News We’re All a Part Of Here we are, all a month 3 Announcements It is our mission as the older with lots to look forward Alfred-Almond Observer to provide 4-5 Video Game Review truthful, unbiased, and accurate to, including the fourth issue information to the student body. Our 6 Cyborgs from The Observer! We are goal is to deliver relevant stories back with a slew of articles focused on both informing and 7 Robotics entertaining the Alfred-Almond entertaining a variety of 8-9 Who is it? community. We strive to promote a emotions including love, positive school climate and will use 10 Kilroy! excitement, and curiosity. In the Observer as a way to give all voices at Alfred-Almond a platform. 11-12 Semi Formal Photos this special February edition, 13 What is Love? learn about holidays in this 2017 Observer Staff month other than Valentine’s 14 The Science of Love Editors in Chief Day, and some of the big Kaitlyn C. 15-6 The History of Cupid upcoming events like NY Abigail H. 17-8 Asian Holidays Fashion Week and the Winter Jessie M. 19 February Holidays Olympics. Delve into the Copy Editors science of love, and possibly Morgan G. Sam Q. 20 NY Fashion Week rethink what you perceive love Chloe M. Sam W. Maya R. -

Pyeongchang Olympic Plaza Gangneung Olympic Park

https://www.pyeongchang2018.com/en/culture/index Everyday, Culture & Festival! Everyday, Culture & Festival! Everyday, Culture & Festival! Everyday, Culture & Festival! Everyday, Culture & Festival! Culture-ICT Pavilion Traditional Korean Pavilion & Bell of Peace Traditional Experience Booth & Outdoor Stage Live Site PyeongChang Culture-ICT Pavilion is a converged cultural space designed for experiencing Traditional Korean Pavilion and Bell of Peace are where visitors can An area for enjoying hands-on experiences of Live Site is where spectators can enjoy live broadcasting of major games, 1330 / +82-2-1330 / 1330 Korea’s major art pieces (PAIK Nam-june Media Art, Modern and experience the essence of Korean culture through Korea’s unique Korean traditional folk culture. various cultural performances, and K-Wave (K-POP) contents with Tourist Information Centre of Korea Tourism Organization Tourism Korea of Centre Information Tourist Olympiad Homepage Homepage Olympiad Contemporary Art) and high technolgies. architectures. high-technology, ICT. Go to the Cultural the to Go Olympic Plaza Tel. 033-350-5157 Tel. 2-4 Gyodong, Gangneung-si, Gangwon Province Gangwon Gangneung-si, Gyodong, 2-4 Main Activity Gangneung Olympic Park Olympic Gangneung Main Activity Main Activity Main Activity Tel. 033-350-2018 Tel. Time 9 - 18 Mar 2018 (10 days) Time Time 10 - 17 Mar 2018 (8 days) 10:00 - 21:00 Time 10 - 17 Mar 2018 (8 days) 9 - 18 Mar 2018 (10 days), 10:00 - 22:00 30 Jangseon-gil, Daegwallyeong-myeon, PyeongChang-gun, Gangwon Province Gangwon PyeongChang-gun, -

2018 Winter Olympic and Paralympic Games, Pyeongchang

2018 Winter Olympic and Paralympic Games, PyeongChang, Republic of Korea Advice for travellers and travelling athletes The XXIII Olympic Winter Games will take place from 9 to 25 February 2018 in PyeongChang, the Republic of Korea. The 2018 Winter Olympics will feature 102 events in 15 sports. The Paralympic Winter Games will take place from 9 to 18 March 2018 and will feature 6 sports. Before travelling Visitors to PyeongChang and possibly to other parts of the Republic of Korea should be aware that they are at risk of infectious diseases such as: o Foodborne and waterborne diseases, e.g. hepatitis A, typhoid fever. o Vectorborne diseases, e.g. malaria, Japanese encephalitis. o Bloodborne and sexually transmitted diseases, e.g. hepatitis B, HIV. o Other diseases, e.g. rabies. A) Immunizations It is recommended that you consult your health professional 4-6 weeks in advance of travel, in order to confirm primary courses and boosters are up to date according to the current national recommendations. Especially: o A single MMR dose should be given to complete the two dose series and all non- immune adult travellers should be vaccinated with two doses of MMR vaccine. Individuals who completed the two dose series or with documented physician diagnosed measles do not need vaccination. o Tetanus- diphtheria booster. o Poliomyelitis booster. o Hepatitis Α vaccine. Hellenic Center for Disease Control & Prevention Department of Interventions in Health Care Facilities Travel Medicine Office www.keelpno.gr, 210 5212000 o Hepatitis B vaccine. o Influenza (flu) vaccine. o Typhoid fever vaccine. o Japanese encephalitis vaccine. -

Event 2 (Of 6)

I N T E R N A T I O N A L S K A T I N G U N I O N HEADQUARTERS ADDRESS AVENUE JUSTE-OLIVIER 17 - CH 1006 LAUSANNE - SWITZERLAND PHONE (+41) 21 612 66 66 FAX (+41) 21 612 66 7 E-MAIL [email protected] Press release 21 February 2018 Cooperation versus individual speed in Team Pursuit finals Wednesday night the Gangneung Oval features the ladies’ and men’s Team Pursuit semifinals and finals in Speed Skating. It doesn’t only come down to speed and stamina anymore, communication and cooperation are of the utmost importance. In the ladies’ event Japan and the Netherlands are the ones to watch and in the men’s event New Zealand are aiming for a historical first ever Speed Skating medal and the second medal in total for their nation at the Olympic Games. Whereas the four fastest teams from the quarter finals advanced to the semis, the event will continue as a knock-out competition in the next phase. The winners of the semifinals will race in the gold-medal race and the losers of the semifinals in the bronze-medal race. Individual speed versus team tactics The Dutch ladies won four of the five individual Speed Skating events so far, they skated an Olympic record in the quarterfinals and they will be defending their Sochi 2014 title, but they are no clear-cut favorites for the gold medal at PyeongChang 2018. Japan won nine of the last 11 World Cup races in this event, including each of the last six, and they hammered out a new world record in 2:50.87 at the Salt Lake City World Cup in December. -

P14 5 Layout 1

14 Established 1961 Sports Thursday, February 22, 2018 Zagitova, 15, smashes skate record as Vonn gets bronze Ridzik recovers from crash in ski cross final to take bronze PYEONGCHANG: Record-breaking Alina Zagitova, Goggia and Ragnhild Mowinckel of Norway. 15, stole the show in figure skating yesterday as But the 2010 winner was delighted to reach the America’s Lindsey Vonn wound up her Olympic podium-the oldest female alpine skier to do so-after downhill career by becoming the oldest female alpine a series of injuries threatened to wreck her career ski medallist in Games history. and ruled her out of Sochi 2014. “If you think what’s Zagitova was breathtaking in the Russian-dominat- happened over the last eight years and what I’ve been ed short programme, breaking the world record set through to get here, I gave it all and to come away just minutes earlier by her team-mate, 18-year-old with a medal is a dream come true,” said Vonn. Evgenia Medvedeva. It put “You’ve got to put things the Russians top of the into perspective. Of course, standings ahead of Friday’s I would have loved a gold free skate, where Zagitova medal but, honestly, this is will attempt to become the amazing and I’m so proud.” youngest women’s singles You’ve got figure skating champion SKI CROSS CHAOS since Tara Lipinski in 1998. to put things In other action yester- They also look set to win day, Russian skier Sergey the first gold of the Games into perspective Ridzik recovered from a for the Olympic Athletes crash in the ski cross final to from Russia, who are com- take bronze, behind peting as neutrals after Canada’s Bredy Leman and Russia’s national team was Marc Bischofberger of banned over a major doping scandal. -

Go Go Pyeongchang!

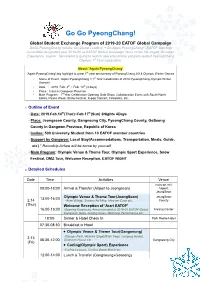

Go Go PyeongChang! Global Student Exchange Program of 2019-20 EATOF Global Campaign GoGo PyeongChang’ means ‘Go Global Leaders! + Go Again PyeongChang!’. EATOF Standing Committee designated year 2019-20 as EATOF Global Campaign Years under the slogan ‘Discover, Experience, Inspire’. Secretariat is going to launch new educational program related PyeongChang Olympic 1st Year celebration. About ‘Again PyeongChang’ ‘Again PyeongChang’:big highlight to greet 1st year anniversary of PyeongChang 2018 Olympic Winter Games • Name of Event : Again PyeongChang ! (1st Year Celebration of 2018 PyeongChang Olympic Winter Games) • Date : 2019. Feb. 8th ~ Feb. 10th (3 days) • Place : Cities in Gangwon Province • Main Program : 1st Year Celebration Opening Gala Show, Collaboration Event with South-North Korea, Peace Week, Snow Festival, K-pop Concert, Fireworks, etc. □ Outline of Event ∙ Date: 2019.Feb.14th(Thur)~Feb.17th(Sun) 3Nights 4Days ∙ Place: Jeongseon County, Gangneung City, PyeongChang County, GoSeong County in Gangwon Province, Republic of Korea ∙ Invitee: 500 University Student from 10 EATOF member countries ∙ Support by Gangwon: Local Stay(Accommodations, Transportation, Meals, Guide, etc) * Roundtrip Airfare will be borne by yourself. ∙ Main Program: Olympic Venue & Theme Tour, Olympic Sport Experience, Snow Festival, DMZ Tour, Welcome Reception, EATOF NIGHT □ Detailed Schedules Date Time Activities Venue Incheon Int’l 00:00-18:00 Arrival & Transfer (Airport to Jeongseon) Airport, JeongSeon 13:00-16:00 Olympic Venue & Theme Tour(JeongSeon) JeongSeon 2.14 -Arari Village, Samtan Art Mine, Hwa’am Cave etc. County (Thur) Welcome Reception of ‘Arari EATOF’ 16:00-18:00 -Opening Ceremony, Announcement of 2019-20 EATOF Global Arirang Center Campaign Years, Arirang Class, Welcome Performance etc. -

Korean Symphony Orchestra

Onsdag 16. januar 2019 kl. 19.30 Wednesday 16th of January 2019 at 7.30 p.m. Gæstespil/On tour 2019 Korea-Denmark Cultural Year Opening Concert KOREAN SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA KOREAN SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Chi-Yong Chung, dirigent/conductor Yubeen Kim, fløjtenist/flutist Sunyoung Seo, sopran/soprano Korean Symphony Orchestra DR Koncerthuset 2018/19 2 Program Onsdag 16. januar kl. 19.30 JOHANN STRAUSS II (1825-1899) Wednesday 16th of January Ouverture til operetten ’Flagermusen’/Overture at 7.30 p.m. from the Operetta ’Die Fledermaus’ DR Koncerthuset CARL NIELSEN (1865-1931) Koncertsalen/The Concert Hall Fløjtekoncert FS 119/Flute Concerto FS 119 Chi-Yong Chung I Allegro moderato dirigent/conductor II Allegretto Solist/soloist: Yubeen Kim, fløjtenist/flutist Yubeen Kim fløjtenist/flutist PAUSE/INTERMISSION (30’) ca. 20.00/8 p.m. Sunyoung Seo sopran/soprano DONG SUN CHAE (1901-1953) Bird, Bird (Seya, Seya) Solist/soloist: Sunyoung Seo, sopran/soprano DONG JIN KIM (1913-2009) 2019 Korea-Denmark New Arirang (Sin Arirang) Cultural Year Opening Concert Solist/soloist: Sunyoung Seo, sopran/soprano KOREAN SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA PETER TJAJKOVSKIJ (1840-1893) Russisk dans (trepak) fra ’Nøddeknækkersuite’ nr. 1, opus 71a/Russian Dance (Trepak) from the ’Nutcracker Suite’ No. 1, Op. 71a GIUSEPPE VERDI (1813-1901) Pace, pace mio dio! fra operaen ‘Skæbnens magt’/ Pace, pace mio dio! from the opera ‘La forza del destino’ Solist/soloist: Sunyoung Seo, sopran/soprano ANTONÍN DVORÁK (1841-1904) Rusalkas sang til månen/Song To The Moon from the opera ‘Rusalka’ Solist/soloist: Sunyoung Seo, sopran/soprano JUNE HEE LIM (F. 1959/BORN 1959) Ouverture fra det symfoniske digt ’Han-River’, opus 71 Overture from the Symphonic Poem ’Han-River’, Op.71 Koncertens varighed: 1 time 50 min. -

Another Brick in the Road Costs Could Be More Than $40,000 Per Block

THURSDAY,FEB. 8, 2018 Inside: 75¢ Get the most out of your Olymic coverage. — Page 1-8D Vol. 89 ◆ No. 269 SERVING CLOVIS, PORTALES AND THE SURROUNDING COMMUNITIES EasternNewMexicoNews.com Company to pick up bill for road work ❏ Public works director says mineral oil will inevitably damage streets. By Eamon Scarbrough STAFF WRITER [email protected] PORTALES — The company that controls a facility from which mineral oil spilled, covering downtown Portales on Jan. 25, has pledged to incur any costs associated with road damage, according to the city’s public works director. John DeSha told the Portales City Council on Tuesday night that in con- versations with J.D. Heiskell, he has been told “they’re absolutely on board with handling all those costs.” Mineral oil, a solvent that DeSha said will inevitably damage the roads in Staff photo: Tony Bullocks some way, was released from a valve in Contract workers on Tuesday afternoon carefully piled the century-old bricks of Clovis’ Main Street while in the early phases of J.D. Heiskell’s Portales feed manufac- infrastructure improvement near the Fifth and Main street intersection. turing facility by vandals, according to officials. The oil leaked onto First Street, Second Street and Abilene Avenue. Officials said last month that repair Another brick in the road costs could be more than $40,000 per block. ❏ Historic Clovis should be back as it was. The work asks for a little bricks of Main Street have been While First and Second are consid- “This is just an extension of more delicacy and attention to moved, but Huerta said it was ered parts of U.S.