The Book of Jubilees and the Midrash Part 3: the Tower of Babel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genesis 10-11: Babel and Its Aftermath

Faith Bible Fellowship Church Sunday School March 22, 2020 Genesis 10-11: Babel and Its Aftermath Understanding the Text Genesis 10: The Table of Nations The Table of Nations begins a new section of Genesis, this time tracing the descendants of Noah. As the new start of humanity, all of the people of the earth are descended from Noah, and this chapter explains the relationships between his descendants and their locations. In the structure of the first eleven chapters of the book, this chapter serves as a transition from the history of the whole human race to a focus on God’s involvement with Israel. The focus of the chapter is on people groups more than on specific people. o Even though the language of “son of” and “fathered” (or “begot”) is used, it is not always indicating a direct ancestry relationship. o A number of the names indicate cities or nations. Some examples (not exhaustive): . Cities or places: Tarshish, Babylon, Erech, Akkad, Shinar, Nineveh, Sidon . Nations or tribes: Kittim, Dodanim, Ludim, Jebusites, Amorites, Girgashites, Hivites o Some names are clearly individuals: Noah, Shem, Ham, Japheth, Peleg, Nimrod, and all the descendants listed in Shem’s line o The point of the table is to explain how the families of the earth moved out to fill the earth according to God’s command (v. 32). Groups of people and cities are not literal descendants of those listed, but the table indicates how they are related to Noah’s sons and then back to Noah. The purpose of the table is to inform Israel of her relationship to her neighbors (see table at the end of the notes). -

Mistranslations of the Prophets' Names in the Holy Quran: a Critical Evaluation of Two Translations

Journal of Education and Practice www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.8, No.2, 2017 Mistranslations of the Prophets' Names in the Holy Quran: A Critical Evaluation of Two Translations Izzeddin M. I. Issa Dept. of English & Translation, Jadara University, PO box 733, Irbid, Jordan Abstract This study is devoted to discuss the renditions of the prophets' names in the Holy Quran due to the authority of the religious text where they reappear, the significance of the figures who carry them, the fact that they exist in many languages, and the fact that the Holy Quran addresses all mankind. The data are drawn from two translations of the Holy Quran by Ali (1964), and Al-Hilali and Khan (1993). It examines the renditions of the twenty five prophets' names with reference to translation strategies in this respect, showing that Ali confused the conveyance of six names whereas Al-Hilali and Khan confused the conveyance of four names. Discussion has been raised thereupon to present the correct rendition according to English dictionaries and encyclopedias in addition to versions of the Bible which add a historical perspective to the study. Keywords: Mistranslation, Prophets, Religious, Al-Hilali, Khan. 1. Introduction In Prophets’ names comprise a significant part of people's names which in turn constitutes a main subdivision of proper nouns which include in addition to people's names the names of countries, places, months, days, holidays etc. In terms of translation, many translators opt for transliterating proper names thinking that transliteration is a straightforward process depending on an idea deeply rooted in many people's minds that proper nouns are never translated or that the translation of proper names is as Vermes (2003:17) states "a simple automatic process of transference from one language to another." However, in the real world the issue is different viz. -

Dating the Tower of Babel Events with Reference to Peleg and Joktan

JOURNAL OF CREATION 31(1) 2017 || PAPERS Dating the Tower of Babel events with reference to Peleg and Joktan Andrew Sibley This paper discusses and seeks to identify the date of the Babel event from the writing of biblical and extra-biblical sources. This is a relevant question for creationists because of questions about the timing of post-Flood climatic changes and human migration. Sources used include the Masoretic Text, the Samaritan Pentateuch, the Septuagint, and the Book of Jubilees, and related historical commentaries. Historical sources suggest that the Babel dispersion occurred in the time of Joktan’s extended family and Peleg’s life. The preferred solution of this paper is to follow the Masoretic Text and the Seder Olam Rabbah commentary that places the Babel event 340 years post-Flood at Peleg’s death. Other texts of the Second Temple period vary from this by only three to six decades, which lends some support to the conclusion. his paper seeks to identify the date of the Babel incident “These are the clans of the sons of Noah, according Twith reference to events in the life of Eber’s sons, Peleg to their genealogies, in their nations, and from these and Joktan. Traditionally the Babel event is associated the nations spread abroad on the earth after the flood.” with a division (Genesis 10:25) in the life of Peleg, and this The problem is that even if Joktan was the elder traditional understanding, relating to confusion of languages brother (which is doubtful because the name implies lesser and demographic scattering, is accepted here. -

The Authority of Scripture: the Puzzle of the Genealogies of Jesus Mako A

The Authority of Scripture: The Puzzle of the Genealogies of Jesus Mako A. Nagasawa, June 2005 Four Main Differences in the Genealogies Provided by Matthew and Luke 1. Is Jesus descended through the line of Solomon (Mt) or the line of Nathan (Lk)? Or both? 2. Are there 27 people from David to Jesus (Mt) or 42 (Lk)? 3. Who was Joseph’s father? Jacob (Mt) or Heli (Lk)? 4. What is the lineage of Shealtiel and Zerubbabel? a. Are they the same father-son pair in Mt as in Lk? (Apparently popular father-son names were repeated across families – as with Jacob and Joseph in Matthew’s genealogy) If not, then no problem. I will, for purposes of this discussion, assume that they are not the same father-son pair. b. If so, then there is another problem: i. Who was Shealtiel’s father? Jeconiah (Mt) or Neri (Lk)? ii. Who was Zerubbabel’s son? Abihud (Mt) or Rhesa (Lk)? And where are these two in the list of 1 Chronicles 3:19-20 ( 19b the sons of Zerubbabel were Meshullam and Hananiah, and Shelomith was their sister; 20 and Hashubah, Ohel, Berechiah, Hasadiah and Jushab-hesed, five)? Cultural Factors 1. Simple remarriage. It is likely that in most marriages, men were older and women were younger (e.g. Joseph and Mary). So it is also likely that when husbands died, many women remarried. This was true in ancient times: Boaz married the widow Ruth, David married the widow Bathsheba after Uriah was killed. It also seems likely to have been true in classical, 1 st century times: Paul (in Rom.7:1-3) suggests that this is at least somewhat common in the Jewish community (‘I speak to those under the Law’ he says) in the 1 st century. -

What's in a Name? a Look at Genealogies… 1. Study Matthew 1:1-18

What’s in a name? A look at genealogies… 1. Study Matthew 1:1-18 and Luke 3:23-38. What do you know about the authors? Matthew was financially well off and had his own house. He was educated and knew how to read and write. As a Jewish publican, a tax collector, fellow Jews despised him. Luke was a physician and companion of Paul. As a Gentile, he recorded as a historian and did careful research. 2. Make a table of the names of each genealogy. What do you notice? Matthew 1:1-18 Abraham-David David-Exile Exile-Jesus 15. David 36. Achim 1. Abraham 8. Amminadab 22. Uzziah 29. Jeconiah (Bathsheba) 37. Eliud 2. Isaac 9. Nahshon 23. Jotham 30. Shealtiel 16. Solomon 38. Eleazar 3. Jacob 10. Salmon (Rahab) 24. Ahaz 31. Zerubbabel 17. Rehoboam 39. Matthan 4. Judah (Tamar) 11. Boaz (Ruth) 25. Hezekiah 32. Abihud 18. Abijah 40. Jacob 5. Perez 12. Obed 26. Manasseh 33. Eliakim 19. Asa 41. Joseph 6. Hezron 13. Jesse 27. Amon 34. Azor 20. Jehoshaphat (Mary) 7. Ram 14. David (Bathsheba) 28. Josiah 35. Zadok 21. Joram 42. Jesus Observations of Matthew : Matthew's accounting of Israel's kings was for the Jewish audience who were interested in Jesus' royal-legal lineage as decreed by the Davidic covenants (2 Sam 7:8-13). This is perhaps emphasized as Matthew lists in a descending order: "...father of..." with the range of genealogy: Abraham-Jesus. By beginning with Abraham, Matthew stresses Jesus’ Jewish ancestry. The genealogical list is short, because Matthew does not list a number of generations. -

Cainan of Luke 3:36 References

article1 is appropriate at this late point, perhaps we often involve ourselves in employ Biblical scholars and I think. eisegesis to support our scientific scholarship in an effort to develop First, Watson was absolutely models rather than yielding our models scientific models which are consistent correct in calling me on the carpet2 to solid exegesis. with the Biblical records as interpreted regarding my comments in my original This tendency may be sympto- within the grammatical-historical Letter to the Editor about his work.3 matic of the second problem: both milieu in which they were written, and He correctly notes that I said that 'the sides seem to be placing natural cease basing those same models on a whole of the context of Genesis 10-11 theology (general revelation) on the stroll through Strong's Concordance is on Mesopotamia' citing Genesis same plane as the supernatural (special alone. 10:15-20 as an obvious example of revelation). This is certainly the case how my statement is false. I admit mea for the progressive creationists and David Fouts, culpa. I should have written: increasingly the case of the young- Dayton, Tennessee, 'the whole of the context of Earthers. As a Biblical scholar and UNITED STATES OF AMERICA. Genesis 10-11 is on Mesopotamia conservative theologian, I would not as the originating point for the yield the testimony of God's Word to REFERENCES spread of the nations described the testimony of God's world. Though therein'. both are subject to interpretation, the 1. Watson, J. A., 1997. The division of the Earth in Peleg's days: tectonic or linguistic? On the other hand, the immediate Word is infallible, whereas the world CEN Tech. -

A Historical Reading of Genesis 11:1–9: the Sumerian Demise and Dispersion Under the Ur Iii Dynasty

JETS 50/4 (December 2007) 693–714 A HISTORICAL READING OF GENESIS 11:1–9: THE SUMERIAN DEMISE AND DISPERSION UNDER THE UR III DYNASTY paul t. penley* i. available options for reading genesis 11:1–9 Three options are available for approaching the question of historicity in Gen 11:1–9: ahistorical primeval event; agnostic historical event; and known historical event. A brief survey of each approach will provide the initial im- petus for pursuing a reading of this pericope as known historical event, and the textual and archaeological evidence considered in the remainder of this article will ultimately identify this known historical event as the demise and dispersion of the last great Sumerian dynasty centered at Ur. 1. Ahistorical primeval event. Robert Davidson in his commentary on the neb text of Genesis 1–11 asserts, “It is only when we come to the story of Abraham in chapter 12 that we can claim with any certainty to be in touch with traditions which reflect something of the historical memory of the Hebrew people.”1 Davidson’s opinion reflects the approach to Genesis 1–11 where the narratives are couched in the guise of primeval events that do not correlate to actual history. Westermann also exemplifies this approach when he opts for reading Gen 11:1–9 through the lens of inaccessible primeval event. Even though he acknowledges that the mention of the historical Babylon “is more in accord with the historical etiologies in which the name of a place is often explained by a historical event,” he hypothesizes that “such an element shows that there are different stages in the growth of 11:1–9.”2 Speiser could also be placed in this category on account of the fact that he proposes pure literary dependence on tablet VI of the Enuma Elish.3 In his estimation the narrative is a reformulated Babylonian tradition and questions of historicity are therefore irrelevant. -

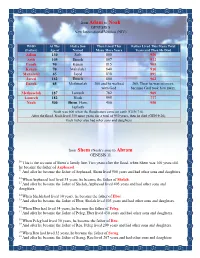

From Adam to Noah GENESIS 5 New International Version (NIV) Adam

from Adam to Noah GENESIS 5 New International Version (NIV) WHO At The Had a Son Then Lived This Father Lived This Many Total (Father) Age of Named Many More Years Years and Then He Died Adam 130 Seth 800 930 Seth 105 Enosh 807 912 Enosh 90 Kenan 815 905 Kenan 70 Mahalalel 840 910 Mahalalel 65 Jared 830 895 Jared 162 Enoch 800 962 Enoch 65 Methuselah 300 and he walked 365, Then he was no more, with God because God took him away. Methuselah 187 Lamech 782 969 Lamech 182 Noah 595 777 Noah 500 Shem, Ham, 450 950 Japheth Noah was 600 when the floodwaters came on earth (GEN 7:6). After the flood, Noah lived 350 more years, for a total of 950 years, then he died (GEN 9:28). Each father also had other sons and daughters from Shem (Noah’s son) to Abram GENESIS 11 10 This is the account of Shem’s family line. Two years after the flood, when Shem was 100 years old, he became the father of Arphaxad. 11 And after he became the father of Arphaxad, Shem lived 500 years and had other sons and daughters. 12 When Arphaxad had lived 35 years, he became the father of Shelah. 13 And after he became the father of Shelah, Arphaxad lived 403 years and had other sons and daughters. 14 When Shelah had lived 30 years, he became the father of Eber. 15 And after he became the father of Eber, Shelah lived 403 years and had other sons and daughters. -

Seven Mountains to Aratta

Seven Mountains to Aratta Searching for Noah's Ark in Iran B.J. Corbin Copyright ©2014 by B.J. Corbin. All rights reserved. 1st Edition Last edited: August 30, 2015 Website: www.bjcorbin.com Follow-up book to The Explorers of Ararat: And the Search for Noah’s Ark by B.J. Corbin and Rex Geissler available at www.noahsarksearch.com. Introduction (draft) The basic premise of the book is this... could there be a relationship between the Biblical "mountains of Ararat" as the landing site of Noah's Ark and the mythical mountain of Aratta as described in ancient Sumerian literature? Both the Biblical Flood mentioned in Genesis chapters 6-8 and The Epic of Gilgamesh in tablet 11 (and other Sumerian texts), seem to be drawing from the same historical flood event. Probable Noah’s Ark landing sites were initially filtered by targeting "holy mountains" in Turkey and Iran. The thinking here is that something as important and significant as where Noah's Ark landed and human civilization started (again) would permeate throughout history. Almost every ancient culture maintains a flood legend. In Turkey, both Ararat and Cudi are considered holy mountains. Generally, Christians hold Mount Ararat in Turkey as the traditional landing site of Noah's Ark, while Muslims adhering to the Koran believe that Mount Cudi (pronounced Judi in Turkish) in southern Turkey is the location where Noah's Ark landed. In Iran, both Damavand and Alvand are considered holy mountains. Comparing the geography of the 4 holy mountains, Alvand best fits the description in Genesis 11:2 of people moving “from the east” into Shinar, if one supports that definition of the verse. -

Nimrod and Esau As Parallel Figures

215 In Search of Nimrod: Nimrod and Esau as Parallel Figures By: GEULA TWERSKY Introduction This study seeks to arrive at an understanding of the enigmatic character Nimrod, the mythical Assyrian conqueror and builder who plays a prom- inent role in the Genesis accounts of the development of evil after the flood. The methodology for arriving at such an understanding lies in an analysis of the parallel relationship between Nimrod and Esau, and by association, Assyria and Edom, the nation-states that they represent. The research presented here leads to an understanding of Esau/Edom as the literary successor of Nimrod and the Assyrian monarchy that he founded. Nimrod Most academic discussions concerning Nimrod focus on the improbable task of identifying him with an extra-biblical, known historical figure.1 S. 1 Cf. for example, Y. Levin, “Nimrod the Mighty, King of Kish, King of Sumer and Akkad,” VT 52.3 (2002): 350–64; Cf. also Nahum Sarna, Genesis, The JPS Torah Commentary, (ed. N. Sarna; Jerusalem: Jewish Publication Society, 1989), 73, who attempts to identify Nimrod with Naram-Sin; some have argued that Nimrod has his roots in a Mesopotamian deity. This was first suggested by J. Grivel, “Nemrod et les écritures cunéiformes,” Transactions of the Society of Biblical Archaeology 3 (1874), p. 136–144, and revived by E. Lipinski, “Nimrod et Assur,” Revue Biblique 73.1 (1966), p. 77–93, who related Nimrod to Marduk in the Bab- ylonian creation myth Enuma elis, “when on high.” Van der Toorn and P. W. van der Horst, Harvard Theological Review 83.1 (1990), p. -

The Gospel According to Luke Luke 3:15-22 ESV February 4-10, 2019

The Gospel According to Luke Luke 3:15-22 ESV February 4-10, 2019 Luke 3:23-38 “Jesus, when he began his ministry, was about thirty years of age, being the son (as was supposed) of Joseph, the son of Heli, the son of Matthat, the son of Levi, the son of Melchi, the son of Jannai, the son of Joseph, the son of Mattathias, the son of Amos, the son of Nahum, the son of Esli, the son of Naggai, the son of Maath, the son of Mattathias, the son of Semein, the son of Josech, the son of Joda, the son of Joanan, the son of Rhesa, the son of Zerubbabel, the son of Shealtiel, the son of Neri, the son of Melchi, the son of Addi, the son of Cosam, the son of Elmadam, the son of Er, the son of Joshua, the son of Eliezer, the son of Jorim, the son of Matthat, the son of Levi, the son of Simeon, the son of Judah, the son of Joseph, the son of Jonam, the son of Eliakim, the son of Melea, the son of Menna, the son of Mattatha, the son of Nathan, the son of David, the son of Jesse, the son of Obed, the son of Boaz, the son of Sala, the son of Nahshon, the son of Amminadab, the son of Admin, the son of Arni, the son of Hezron, the son of Perez, the son of Judah, the son of Jacob, the son of Isaac, the son of Abraham, the son of Terah, the son of Nahor, the son of Serug, the son of Reu, the son of Peleg, the son of Eber, the son of Shelah, the son of Cainan, the son of Arphaxad, the son of Shem, the son of Noah, the son of Lamech, the son of Methuselah, the son of Enoch, the son of Jared, the son of Mahalaleel, the son of Cainan, the son of Enos, the son of Seth, the son of Adam, the son of God.” Luke 3:23-38 ESV This passage can be described as “Biblical flyover country” - seemingly not very exciting but vitally important if we are willing to take the time to explore. -

SETTING the STAGE “The Book of the Genealogy of Jesus Christ, the S

MATTHEW 1:1-17 DRAMATIC EVENTS IN AN OUT-OF-THE-WAY PLACE: SETTING THE STAGE “The book of the genealogy of Jesus Christ, the son of David, the son of Abraham. “Abraham was the father of Isaac, and Isaac the father of Jacob, and Jacob the father of Judah and his brothers, and Judah the father of Perez and Zerah by Tamar, and Perez the father of Hezron, and Hezron the father of Ram, and Ram the father of Amminadab, and Amminadab the father of Nahshon, and Nahshon the father of Salmon, and Salmon the father of Boaz by Rahab, and Boaz the father of Obed by Ruth, and Obed the father of Jesse, and Jesse the father of David the king. “And David was the father of Solomon by the wife of Uriah, and Solomon the father of Rehoboam, and Rehoboam the father of Abijah, and Abijah the father of Asaph, and Asaph the father of Jehoshaphat, and Jehoshaphat the father of Joram, and Joram the father of Uzziah, and Uzziah the father of Jotham, and Jotham the father of Ahaz, and Ahaz the father of Hezekiah, and Hezekiah the father of Manasseh, and Manasseh the father of Amos, and Amos the father of Josiah, and Josiah the father of Jechoniah and his brothers, at the time of the deportation to Babylon. “And after the deportation to Babylon: Jechoniah was the father of Shealtiel, and Shealtiel the father of Zerubbabel, and Zerubbabel the father of Abiud, and Abiud the father of Eliakim, and Eliakim the father of Azor, and Azor the father of Zadok, and Zadok the father of Achim, and Achim the father of Eliud, and Eliud the father of Eleazar, and Eleazar the father of Matthan, and Matthan the father of Jacob, and Jacob the father of Joseph the husband of Mary, of whom Jesus was born, who is called Christ.