Functions of Ontario Legislative Committees: a Content Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report of the Select Committee on Electoral Reform

Legislative Assemblée Assembly législative of Ontario de l'Ontario SELECT COMMITTEE ON ELECTORAL REFORM REPORT ON ELECTORAL REFORM 2nd Session, 38th Parliament 54 Elizabeth II Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Ontario. Legislative Assembly. Select Committee on Electoral Reform Report on electoral reform [electronic resource] Issued also in French under title: Rapport de la réforme électorale. Electronic monograph in PDF format. Mode of access: World Wide Web. ISBN 0-7794-9375-3 1. Ontario. Legislative Assembly—Elections. 2. Elections—Ontario. 3. Voting—Ontario. I. Title. JL278 O56 2005 324.6’3’09713 C2005-964015-4 Legislative Assemblée Assembly législative of Ontario de l'Ontario The Honourable Mike Brown, M.P.P., Speaker of the Legislative Assembly. Sir, Your Select Committee on Electoral Reform has the honour to present its Report and commends it to the House. Caroline Di Cocco, M.P.P., Chair. Queen's Park November 2005 SELECT COMMITTEE ON ELECTORAL REFORM COMITÉ SPÉCIAL DE LA RÉFORME ÉLECTORALE Room 1405, Whitney Block, Toronto, Ontario M7A 1A2 SELECT COMMITTEE ON ELECTORAL REFORM MEMBERSHIP LIST CAROLINE DI COCCO Chair NORM MILLER Vice-Chair WAYNE ARTHURS KULDIP S. KULAR RICHARD PATTEN MICHAEL D. PRUE MONIQUE M. SMITH NORMAN STERLING KATHLEEN O. WYNNE Anne Stokes Clerk of the Committee Larry Johnston Research Officer i CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 Electoral Systems 1 Citizens’ Assembly Terms of Reference 2 Composition of the Assembly 2 Referendum Issues 4 Review of Electoral Reform 5 Future Role 5 List of Recommendations 6 INTRODUCTION 9 Mandate 9 Research Methodology 10 Assessment Criteria 10 Future Role 11 Acknowledgements 11 I. -

'Turncoats, Opportunists, and Political Whores': Floor Crossers in Ontario

“‘Turncoats, Opportunists, and Political Whores’: Floor Crossers in Ontario Political History” By Patrick DeRochie 2011-12 Intern Ontario Legislature Internship Programme (OLIP) 1303A Whitney Block Queen’s Park Toronto, Ontario M7A 1A2 Phone: 416-325-0040 [email protected] www.olipinterns.ca www.facebook.com/olipinterns www.twitter.com/olipinterns Paper presented at the 2012 Annual meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association Edmonton, Alberta Friday, June 15th, 2012. Draft: DO NOT CITE 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank the following people for their support, advice and openness in helping me complete this research paper: Gilles Bisson Sean Conway Steve Gilchrist Henry Jacek Sylvia Jones Rosario Marchese Lynn Morrison Graham Murray David Ramsay Greg Sorbara Lise St-Denis David Warner Graham White 3 INTRODUCTION When the October 2011 Ontario general election saw Premier Dalton McGuinty’s Liberals win a “major minority”, there was speculation at Queen’s Park that a Member of Provincial Parliament (MPP) from the Progressive Conservative (PC) Party or New Democratic Party (NDP) would be induced to cross the floor. The Liberals had captured fifty-three of 107 seats; the PCs and NDP, thirty-seven and seventeen, respectively. A Member of one of the opposition parties defecting to join the Liberals would have definitively changed the balance of power in the Legislature. Even with the Speaker coming from the Liberals’ ranks, a floor crossing would give the Liberals a de facto majority and sufficient seats to drive forward their legislative agenda without having to rely on at least one of the opposition parties. A January article in the Toronto Star revealed that the Liberals had quietly made overtures to at least four PC and NDP MPPs since the October election, 1 meaning that a floor crossing was a very real possibility. -

Provincial Legislatures

PROVINCIAL LEGISLATURES ◆ PROVINCIAL & TERRITORIAL LEGISLATORS ◆ PROVINCIAL & TERRITORIAL MINISTRIES ◆ COMPLETE CONTACT NUMBERS & ADDRESSES Completely updated with latest cabinet changes! 144 / PROVINCIAL RIDINGS PROVINCIAL RIDINGS British Columbia Surrey-Green Timbers ............................Sue Hammell ....................................154 Surrey-Newton........................................Harry Bains.......................................152 Total number of seats ................79 Surrey-Panorama Ridge..........................Jagrup Brar........................................153 Liberal..........................................46 Surrey-Tynehead.....................................Dave S. Hayer...................................154 New Democratic Party ...............33 Surrey-Whalley.......................................Bruce Ralston....................................156 Abbotsford-Clayburn..............................John van Dongen ..............................157 Surrey-White Rock .................................Gordon Hogg ....................................154 Abbotsford-Mount Lehman....................Michael de Jong................................153 Vancouver-Burrard.................................Lorne Mayencourt ............................155 Alberni-Qualicum...................................Scott Fraser .......................................154 Vancouver-Fairview ...............................Gregor Robertson..............................156 Bulkley Valley-Stikine ...........................Dennis -

GOVERNMENT Nonsense Public-Private Partnerships Are Not Subsidies

cover by simon vodrey Horse Sense & GOVERNMENT Nonsense Public-Private Partnerships Are Not Subsidies The Ontario government’s THE COMEDIAN GROUCHO MARX ONCE COMMENTED decision to end the Slots that: “Politics is the art of looking for trouble, finding it everywhere, diagnosing it incorrectly and applying the wrong remedies.” That observation may well describe at Racetracks Program the Ontario government’s decision to abruptly end the Slots at Racetracks Program, a has a detrimental effect successful revenue-sharing program that has, for almost 15 years, mutually benefited for Ontario’s vibrant the government, the horseracing and equine industries and many small towns in rural Ontario. horseracing and equine industries. The vehicle for the Ontario government’s unexpected decision was its March 27, 2012 Budget when Finance Minister Dwight Duncan rose to his feet at Queen’s Park and unveiled the document entitled Strong Action for Ontario. It outlined how Premier Dalton McGuinty’s Liberal government would eliminate the province’s massive $15-billion deficit within the next five years. Ontario horsemen, jockeys, 30 OTTAWALIFE AUGUST 2012 PHOTO: COURTESY RCR Since its inception in 1998, the breeders, equine suppliers, black- smiths, saddlers, veterinarians Slots at Racetracks Program earned Ontario roughly and farmers had no warning that contained within the 332-page a billion dollars in revenue every single year. document was a proposed initiative named Modernizing the Ontario Lottery and Gaming Corporation (OLG), industry and a calculated conclusion thought we could play off of one which would eliminate the Slots at based on social perception. another, allowing both horseracing Racetracks Program by March 31, 2013, (through bets placed on horses) and threatening the sustainability of In the 1990s, knowing that slot the slot machines to be profitable. -

Glebe Report Are Those of Our EDITORIAL NOTES Contributors

Traffic plan for the Exhibition 1 1 1 LOO.ft 1;1 Lansdowne Park administration will once again be pro- EEEEE viding manned "Local Traffic Only" barriers at the locations shown on the map. Local residents and their guests on affected streets may apply to Lansdowne Park Administration (adjacent to Civic Centre box office at , i E' ..o.,e.1 I i .. * Arena Gate 1) or the Central Canada Exhibition Assoc- CATHERINE ST ''' E.4 I F---- - e ..... .. s iation office ( at r: VI =-.'- located the Bank Street entrance of -..2:L......L.------------ the Coliseum building ) for Local Que wa Residents/Guests 'I SABELaST". ; i'2 . I7i.Ej >, t7, .._z77 Vehicle Identification card. OS( 00, 1 In a STRATHCON-R"AVE.rr-'4'''t,, AVE addition "Do Not Enter" barrier and flashing 1 si- = beacons will be placed at O'Connor Street and Fifth Ave ii_ f W i in order to reduce incidents of "wrong way" traffic Ct woo L ' Of. 'EMILY ) For information or questions call Rick Desrosiers at 564-1504 between 8:30 and 16:00, Monday to Friday. cn ffr._...._.,...,),c4 (.[. r., FIRST I Z AVE. 1987 EX STREET CLOSURE mlip > ., - Z ,- 't gg BARRICADES 10 I ,u / AUGUST 20 - 30, 1987 Z i , I -i 0 Iv A !b. 0:. 0:i 4111% Thursday, August 20, 1987 - 08:00 - 24:00 0 rimavw Friday, August 21, 1987 -tz FI FTH AVE . , - 08:00 - 24:00 AL Ilk I ,r1 al i5I.., If Saturday, August 22, 1987 S ..! 1..._ 'l - 08:00 - 24:00 ..."0.11.... -

ALPHABETICAL LISTING of ONTARIO MEMBERS of PROVINCIAL PARLIAMENT at MARCH 20, 2007

ALPHABETICAL LISTING OF ONTARIO MEMBERS OF PROVINCIAL PARLIAMENT at MARCH 20, 2007 Member of Provincial Parliament Riding Email Ted Arnott Waterloo-Wellington [email protected] Wayne Arthurs Pickering-Ajax-Uxbridge [email protected] Bas Balkissoon Scarborough-Rouge River [email protected] Toby Barrett Haldimand-Norfolk-Brant [email protected] Hon Rick Bartolucci Sudbury [email protected] Hon Christopher Bentley London West [email protected] Lorenzo Berardinetti Scarborough Southwest [email protected] Gilles Bisson Timmins-James Bay [email protected] Hon Marie Bountrogianni Hamilton Mountain [email protected] Hon James J. Bradley St. Catharines [email protected] Hon Laurel C. Broten Etobicoke-Lakeshore [email protected] Michael A. Brown Algoma-Manitoulin [email protected] Jim Brownell Stormont-Dundas-Charlottenburgh [email protected] Hon Michael Bryant St. Paul's [email protected] Hon David Caplan Don Valley East [email protected] Hon Donna H. Cansfield Etobicoke Centre [email protected] Hon Mary Anne V. Chambers Scarborough East [email protected] Hon Michael Chan Markham [email protected] Ted Chudleigh Halton [email protected] Hon Mike Colle Eglinton-Lawrence [email protected] Kim Craitor Niagara Falls [email protected] Bruce Crozier Essex [email protected] Bob Delaney Mississauga West [email protected] Vic Dhillon Brampton West-Mississauga [email protected] Hon Caroline Di Cocco Sarnia-Lambton [email protected] Cheri DiNovo Parkdale-High Park [email protected] Hon Leona Dombrowsky Hastings-Frontenac-Lennox & Addington [email protected] Brad Duguid Scarborough Centre [email protected] Hon Dwight Duncan Windsor-St. -

Ottawa Centre

Ottawa Area MPPs January, 2017 Ottawa Centre Party Name Contact #’s Web Site Notes Liberal Hon Yasir Tel: 416-325-0408 www.yasirnaqvi.onmpp.ca Attorney General Naqvi Fax: 416-325-6067 Email: [email protected] Commissioner, Board of Address: 109 Catherine Street Internal Economy Ottawa, Ontario K2P 0P4 Tel: 613-722-6414 Government House Fax: 613-722-6703 Leader 2014 Election: 52%, PC 18%, NDP 20% Meeting set for February 11th at 4:00 pm Profile: Naqvi was born and raised in Karachi, Pakistan and immigrated to Canada with his family in 1988 at the age of 15 after his father was arrested for leading a pro-democracy march. Naqvi attended McMaster University and the University of Ottawa Law School. He was called to the Bar in Ontario in 2001 and began practising in international trade law at Lang Michener LLP and eventually became a partner. He left Lang Michener in 2007 to join the Centre for Trade Policy and Law at Carleton University. He was President of the Liberal Party of Ontario. The Ottawa Citizen named Naqvi as one of its "People to Watch in 2010", with a profile in 9 January 2010 Saturday Observer headlined "Yasir Naqvi, he's a firecracker". Ottawa Life magazine also included him in its Tenth Annual "Top 50 People in the Capital" list for 2010. In a September 2011 column, Adam Radwanski of The Globe and Mail called Naqvi "possibly the hardest-working constituency MPP in the province." Prior to entering politics he volunteered with a number of community associations including the Centretown Community Health Centre and the Ottawa Food Bank. -

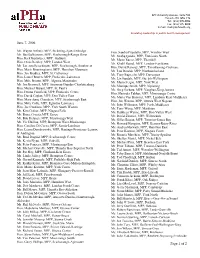

June 7, 2006 Page 1 of 2

425 University Avenue, Suite 502 Toronto ON M5G 1T6 Tel: (416) 595-0006 Fax: (416) 595-0030 E-mail: [email protected] Providing leadership in public health management June 7, 2006 Mr. Wayne Arthurs, MPP, Pickering-Ajax-Uxbridge Hon. Sandra Pupatello, MPP, Windsor West Mr. Bas Balkissoon, MPP, Scarborough-Rouge River Mr. Shafiq Qaadri, MPP, Etobicoke North Hon. Rick Bartolucci, MPP, Sudbury Mr. Mario Racco, MPP, Thornhill Hon. Chris Bentley, MPP, London West Mr. Khalil Ramal, MPP, London-Fanshawe Mr. Lorenzo Berardinetti, MPP, Scarborough- Southwest Hon. David Ramsay, MPP, Timiskaming-Cochrane Hon. Marie Bountrogianni, MPP, Hamilton Mountain Mr. Lou Rinaldi, MPP, Northumberland Hon. Jim Bradley, MPP, St. Catharines Mr. Tony Ruprecht, MPP, Davenport Hon. Laurel Broten, MPP, Etobicoke-Lakeshore Ms. Liz Sandals, MPP, Guelph-Wellington Hon. Mike Brown, MPP, Algoma-Manitoulin Mr. Mario Sergio, MPP, York West Mr. Jim Brownell, MPP, Stormont-Dundas-Charlottenburg Ms. Monique Smith, MPP, Nipissing Hon. Michael Bryant, MPP, St. Paul’s Mr. Greg Sorbara, MPP, Vaughan-King-Aurora Hon. Donna Cansfield, MPP, Etobicoke Centre Hon. Harinder Takhar, MPP, Mississauga Centre Hon. David Caplan, MPP, Don Valley East Ms. Maria Van Bommel, MPP, Lambton-Kent-Middlesex Hon. Mary Anne Chambers, MPP, Scarborough East Hon. Jim Watson, MPP, Ottawa West-Nepean Hon. Mike Colle, MPP, Eglinton-Lawrence Mr. John Wilkinson, MPP, Perth-Middlesex Hon. Joe Cordiano, MPP, York South-Weston Mr. Tony Wong, MPP, Markham Mr. Kim Craitor, MPP, Niagara Falls Ms. Kathleen Wynne, MPP, Don Valley West Mr. Bruce Crozier,MPP, Essex Mr. David Zimmer, MPP, Willowdale Mr. Bob Delaney, MPP, Mississauga West Mr. Gilles Bisson, MPP, Timmins-James Bay Mr. -

C-10 CANADA YEAR BOOK the Hon. Michel Page Minister Of

C-10 CANADA YEAR BOOK The Hon. Michel Page The Hon. Sean Conway Minister of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food Minister of Mines and Government House Leader The Hon. Yvon Picotte The Hon. James Bradley Minister of Recreation, Hunting and Fishing, and Minister of the Environment Minister responsible for Fisheries The Hon. Ian G. Scott The Hon. John Ciaccia Attorney General and Minister responsible for Native Minister of Energy and Resources Affairs The Hon. Marc-Yvan Cote The Hon. Jack Riddell Minister of Transport Minister of Agriculture and Food The Hon. Therese Lavoie-Roux The Hon. John Eakins Minister of Health and Social Services Minister of Municipal Affairs The Hon. Pierre Paradis The Hon. Vincent Kerrio Minister of Municipal Affairs Minister of Natural Resources The Hon. Daniel Johnson The Hon. Hugh O'Neil President of the Treasury Board and Minister respon Minister of Tourism and Recreation sible for Administration The Hon. John Sweeney The Hon. Pierre Fortier Minister of Community and Social Services Minister responsible for Finance and Privatization The Hon. Murray Elston Chairman of the Management Board, Minister of The Hon. Andre Bourbeau Financial Institutions and Chairman of Cabinet Minister of Manpower and Income Security The Hon. William Wrye The Hon. Pierre MacDonald Minister of Consumer and Commercial Relations Minister of Industry, Commerce and Technology The Hon. Bernard Grandmaitre The Hon. Paul Gobeil Minister of Revenue and Minister responsible for Minister of International Affairs Francophone Affairs The Hon. Yves Seguin The Hon. Alvin Curling Minister of Revenue and Minister of Labour Minister of Skills Development The Hon. Andre Vallerand The Hon. -

Journals of the Legislative Assmbly of the Province of Ontario, 1987-1989, Being the First Session

c/i 2. y 3-57 c. 9 REJ Ontario JOURNALS OF THE Legislative Assembly OF THE PROVINCE OF ONTARIO From November 3rd, 1987 to January 7th, 1988 Both Days inclusive and from February 8th to February llth, 1988 Both Days inclusive and from April 5th to June 29th, 1988 Both Days inclusive and from October 17th, 1988 to March 2nd, 1989 Both Days inclusive BEING THE First Session of the Thirty-Fourth Parliament of Ontario SESSION 1987-88-89 IN THE THIRTY-SIXTH, THIRTY-SEVENTH AND THIRTY-EIGHTH YEARS OF THE REIGN OF OUR SOVEREIGN LADY QUEEN ELIZABETH II VOL. CXXI INDEX Journals of the Legislative Assembly of Ontario 36-37-38 ELIZABETH II, 1987-88-89 - - First Session Thirty-fourth Parliament ADJOURNMENT DEBATES: November 17, 19, 24; December 8, 10, 1987; April 14, 1988; January 12, 1989. ARMENIAN EARTHQUAKE: Canadian and Ontario flags flown at half-mast in remembrance of those who lost their lives December 12, 1988. B BOARD OF INTERNAL ECONOMY: Order in Council appointing Chairman and Commissioners November 4, 1987. Order in Council deleting the name of one Commissioner and substituting the name of another in lieu thereof February 13, 1989. BUDGET DEBATE: Budget and Budget Papers, 1988 tabled April 20, 1988. Dates considered April 25, 26, 27, 28; May 4, 5, 9, 19, 30; June 2, 1988; Feb- ruary 22; March 2, 1989. [iii] iv INDEX 1987/88/89 Motion for approval April 25, 1988; carried on division March 2, 1989. Amendments to motion for approval April 26, 1988; lost on division- March 2, 1989. -

Provincial Legislatures

PROVINCIAL LEGISLATURES ◆ PROVINCIAL & TERRITORIAL LEGISLATORS ◆ PROVINCIAL & TERRITORIAL MINISTRIES ◆ COMPLETE CONTACT NUMBERS & ADDRESSES Completely updated with latest cabinet changes! 80 / PROVINCIAL RIDINGS PROVINCIAL RIDINGS British Columbia Surrey-Cloverdale...................................Kevin Falcon.......................................90 Surrey-Green Timbers ............................Sue Hammell ......................................90 Total number of seats ................79 Surrey-Newton........................................Harry Bains.........................................88 Liberal..........................................46 Surrey-Panorama Ridge..........................Jagrup Brar..........................................88 New Democratic Party ...............33 Surrey-Tynehead.....................................Dave S. Hayer.....................................90 Surrey-Whalley.......................................Bruce Ralston......................................92 Abbotsford-Clayburn..............................John van Dongen ................................93 Surrey-White Rock .................................Gordon Hogg ......................................90 Abbotsford-Mount Lehman....................Michael de Jong..................................89 Vancouver-Burrard.................................Lorne Mayencourt ..............................91 Alberni-Qualicum...................................Scott Fraser .........................................90 Vancouver-Fairview ...............................Gregor -

Fall 2020 OAFP Newsletter Outline.Indd

Fall 2020 Contents Obituary Doug Wiseman 1 Jim Taylor 2 David Ramsay 4 Marietta L. D. Roberts 6 Article Gary Malkowski story 8 Amethyst Room 11 Regions of Ontario - Kitchener Waterloo 12 and Region Interview Patrick Brown 13 Helena Jaczek 15 Irene Mathyssen 18 Farewell to Victoria E., Victoria S. + 21 welcome to Cassandra & David Article Richard Patten’s international work 23 Article In the Family DNA 24 In Loving Memory of Douglas Jack Wiseman (July 21, 1930 – August 1, 2020) Progressive Conservative Member of Provincial Parliament for Lanark in the 29th, 30th, 31st, 32nd and 33rd Parliament (October 21, 1971-September 9, 1987) Lanark-Renfrew in the 34th Parliament (September 9, 1987-September 5, 1990) Doug Wiseman was Minister of Government Services, Minister Without Portfolio, Parliamentary Assistant to the Minister of Health. He served on 3 Select Committees; Land Drainage, Inquiring into Hydro’s Proposed Bulk Power Rates, Inco/Falconbridge Layoffs, and 7 Standing Committees; Re- sources Development, Public Accounts, Estimates, Social Development, Members’ Services, General Government, Regulations and Private Bills. Biographical Snapshot • Educated at Smiths Falls College • Farmed Chaloa Acres, just east of Perth in the 60’s and 70’s, showing his prized Charolais cattle and developed a prominent cow-calf business in the region • After retirement from politics, he owned and operated Wiseman’s Shoes in Prescott and founded Wiseman’s Shoes in Perth • Public school board chair, and a trustee of St. Paul’s United Church in Perth, Ontario. • Awarded Queen’s Jubilee Medal in 2012 Douglas Wiseman “Doug Wiseman was from the riding of Lanark-Renfrew in Eastern Ontario.