Forget Memory Creating Better Lives for People with Dementia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Improving Later Life

Improving later life. Improving later life. Age UK Tavis House 1–6 Tavistock Square London WC1H 9NA 0800 169 80 80 www.ageuk.org.uk Age UK is the new force combining Age Concern and Help the Aged. With almost 120 years of combined history to draw on, we are bringing together our talents, services and solutions to do more to enrich the lives of people in later life. We have brought together leading experts in the field to create this authoritative guide to ageing better. We are grateful to all the contributors who gave their time freely to make this vision a reality. Project editors: Professor James Goodwin and Phil Rossall Improving later life. These days, there’s a huge amount of information available on how to age well and what to do to ensure a healthier and wealthier later life. Much of this advice is based on sound evidence, but much is confusing and often contradictory – what’s good for us one day can all too often be bad for us the next. Age UK is committed to promoting research and giving clear and reliable advice on all aspects of ageing. So we asked over 20 of the world’s leading experts on ageing, including a wide range of eminent scientists and doctors, for their advice on ageing better. This has then been summarised in our top ten tips on ageing well. Each chapter focuses on one of the most important aspects of ageing and gives the advice of the expert, in his or her own words, together with a summary of the evidence on which that advice is based. -

Customizable • Ease of Access Cost Effective • Large Film Library

CUSTOMIZABLE • EASE OF ACCESS COST EFFECTIVE • LARGE FILM LIBRARY www.criterionondemand.com Criterion-on-Demand is the ONLY customizable on-line Feature Film Solution focused specifically on the Post Secondary Market. LARGE FILM LIBRARY Numerous Titles are Available Multiple Genres for Educational from Studios including: and Research purposes: • 20th Century Fox • Foreign Language • Warner Brothers • Literary Adaptations • Paramount Pictures • Justice • Alliance Films • Classics • Dreamworks • Environmental Titles • Mongrel Media • Social Issues • Lionsgate Films • Animation Studies • Maple Pictures • Academy Award Winners, • Paramount Vantage etc. • Fox Searchlight and many more... KEY FEATURES • 1,000’s of Titles in Multiple Languages • Unlimited 24-7 Access with No Hidden Fees • MARC Records Compatible • Available to Store and Access Third Party Content • Single Sign-on • Same Language Sub-Titles • Supports Distance Learning • Features Both “Current” and “Hard-to-Find” Titles • “Easy-to-Use” Search Engine • Download or Streaming Capabilities CUSTOMIZATION • Criterion Pictures has the rights to over 15000 titles • Criterion-on-Demand Updates Titles Quarterly • Criterion-on-Demand is customizable. If a title is missing, Criterion will add it to the platform providing the rights are available. Requested titles will be added within 2-6 weeks of the request. For more information contact Suzanne Hitchon at 1-800-565-1996 or via email at [email protected] LARGE FILM LIBRARY A Small Sample of titles Available: Avatar 127 Hours 2009 • 150 min • Color • 20th Century Fox 2010 • 93 min • Color • 20th Century Fox Director: James Cameron Director: Danny Boyle Cast: Sam Worthington, Sigourney Weaver, Cast: James Franco, Amber Tamblyn, Kate Mara, Michelle Rodriguez, Zoe Saldana, Giovanni Ribisi, Clemence Poesy, Kate Burton, Lizzy Caplan CCH Pounder, Laz Alonso, Joel Moore, 127 HOURS is the new film from Danny Boyle, Wes Studi, Stephen Lang the Academy Award winning director of last Avatar is the story of an ex-Marine who finds year’s Best Picture, SLUMDOG MILLIONAIRE. -

1Guitar PDF Songs Index

Material on Guitar Website Reference Beginning Guitar Music Guitar Cover Beginning Chords Fingerpicking Bass Runs for Guitar Guitar Christmas Song List Guitar Care Guitar PDF Song Index 1/4/2017 Good Reader Web Downloads to Goodreader How to Use Goodreader Downloading Files to the iPad from iTunes Saving Your Internet Passwords Corrected Guitar and PDF 509 Songs 1/4/2017 A Bushel and a Peck Bad Moon Rising A White Sport Coat Ballad of Davy Crockett All I Ask of You Ballad of Green Berets All My Ex’s Live in Texas Battle Hymn of Aging All My Lovin’ Be Our Guest All My Trials Beautiful Brown Eyes Always On My Mind Because of You Am I That Easy to Forget Beep Beep Amanda - bass runs Beer for My Horses + tab Amazing Grace - D Begin the Beguine A America the Beautiful Besame Mucho American Pie Beyond the Reef Amor Big Rock Candy Mountain And I Love Her Blame It On Bossa Nova And I Love You So Blowin’ in the Wind Annie’s Song Blue Bayou April Love Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain - D, C Aquarius Blue Blue Skies Are You Lonesome Tonight Blueberry Hill Around the World in 80 Days Born to Lose As Tears Go By Both Sides Now Ashokan Farewell Breaking Up Is Hard to Do Autumn Leaves Bridge Over Troubled Water Bring Me Sunshine Moon Baby Blue D, A Bright Lights Big City Back Home Again Bus Stop Bad, Bad Leroy Brown By the Time I Get to Phoenix Bye Bye Love Dream A Little Dream of Me Edelweiss Cab Driver Eight Days A Week Can’t Help Falling El Condor Pasa + tab Can’t Smile Without You Elvira D, C, A Careless Love Enjoy Yourself Charade Eres Tu Chinese Happy -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 2001, Tanglewood

SEMI OIAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR BERNARD HAITINK PRINCIPAL GUEST CONDUCTOR • i DALE CHIHULY INSTALLATIONS AND SCULPTURE / "^ik \ *t HOLSTEN GALLERIES CONTEMPORARY GLASS SCULPTURE ELM STREET, STOCKBRIDGE, MA 01262 . ( 41 3.298.3044 www. holstenga I leries * Save up to 70% off retail everyday! Allen-Edmoi. Nick Hilton C Baccarat Brooks Brothers msSPiSNEff3svS^:-A Coach ' 1 'Jv Cole-Haan v2^o im&. Crabtree & Evelyn OB^ Dansk Dockers Outlet by Designs Escada Garnet Hill Giorgio Armani .*, . >; General Store Godiva Chocolatier Hickey-Freeman/ "' ft & */ Bobby Jones '.-[ J. Crew At Historic Manch Johnston & Murphy Jones New York Levi's Outlet by Designs Manchester Lion's Share Bakery Maidenform Designer Outlets Mikasa Movado Visit us online at stervermo OshKosh B'Gosh Overland iMrt Peruvian Connection Polo/Ralph Lauren Seiko The Company Store Timberland Tumi/Kipling Versace Company Store Yves Delorme JUh** ! for Palais Royal Phone (800) 955 SHOP WS »'" A *Wtev : s-:s. 54 <M 5 "J* "^^SShfcjiy ORIGINS GAUCftV formerly TRIBAL ARTS GALLERY, NYC Ceremonial and modern sculpture for new and advanced collectors Open 7 Days 36 Main St. POB 905 413-298-0002 Stockbridge, MA 01262 Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Ray and Maria Stata Music Directorship Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor One Hundred and Twentieth Season, 2000-2001 SYMPHONY HALL CENTENNIAL SEASON Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Peter A. Brooke, Chairman Dr. Nicholas T. Zervas, President Julian Cohen, Vice-Chairman Harvey Chet Krentzman, Vice-Chairman Deborah B. Davis, Vice-Chairman Vincent M. O'Reilly, Treasurer Nina L. Doggett, Vice-Chairman Ray Stata, Vice-Chairman Harlan E. Anderson John F. Cogan, Jr. Edna S. -

PRACHTER: Hi, I'm Richard Prachter from the Miami Herald

Bob Garfield, author of “The Chaos Scenario” (Stielstra Publishing) Appearance at Miami Book Fair International 2009 PACHTER: Hi, I’m Richard Pachter from the Miami Herald. I’m the Business Books Columnist for Business Monday. I’m going to introduce Chris and Bob. Christopher Kenneally responsible for organizing and hosting programs at Copyright Clearance Center. He’s an award-winning journalist and author of Massachusetts 101: A History of the State, from Red Coats to Red Sox. He’s reported on education, business, travel, culture and technology for The New York Times, The Boston Globe, the LA Times, the Independent of London and other publications. His articles on blogging, search engines and the impact of technology on writers have appeared in the Boston Business Journal, Washington Business Journal and Book Tech Magazine, among other publications. He’s also host and moderator of the series Beyond the Book, which his frequently broadcast on C- SPAN’s Book TV and on Book Television in Canada. And Chris tells me that this panel is going to be part of a podcast in the future. So we can look forward to that. To Chris’s left is Bob Garfield. After I reviewed Bob Garfield’s terrific book, And Now a Few Words From Me, in 2003, I received an e-mail from him that said, among other things, I want to have your child. This was an interesting offer, but I’m married with three kids, and Bob isn’t quite my type, though I appreciated the opportunity and his enthusiasm. After all, Bob Garfield is a living legend. -

Super Saturday, Wonderful Weekend Draw Blow For

SATURDAY, OCTOBER 1, 2011 732-747-8060 $ TDN Home Page Click Here SUPER SATURDAY, WONDERFUL WEEKEND DRAW BLOW FOR ARC FAVORITES By any measure, it is a Super Saturday today, as no Ante-post favorites So You Think (NZ) (High fewer than 13 graded events, each with varying Chaparral {Ire}) and Sarafina (Fr) (Refuse To Bend {Ire}) degrees of impact on Breeders= Cup weekend Nov. 4 will be forced to overcome wide post positions in and 5, will be contested from >sea to shining sea.= The tomorrow=s G1 Qatar Prix de l=Arc de Triomphe at races have attracted 3 reigning Longchamp. Only Dalakhani (Ire) and Sakhee have Eclipse Award winners, a managed to win from double-figure stalls since 1993, quartet of others who were and both Sarafina (13) and So You Think (14) face an among finalists for instant disadvantage as they bid to crown successful championship honors and a campaigns. So You Think, who will be partnered once Classic-winning 3-year-old of again by Seamus Heffernan after the pair were this season. For good measure, successful in the July 2 G1 Eclipse S. at Sandown and two-time Eclipse Award winner G1 Irish Champion S. at Leopardstown Sept. 3, was and 2010 Horse of the Year not the only Ballydoyle raider to fare badly with the finalist Goldikova (Ire) (Anabaa) draw, as stable companion Treasure Beach (GB) (Galileo will prep for a fourth {Ire}) will exit from the 12 hole under Colm consecutive victory in the GI O=Donoghue. Arc Preview cont. p4 Stay Thirsty Horsephotos Breeders= Cup Mile when she goes postward in the G1 Prix de la Foret on the Arc undercard. -

For Immediate Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE BC’S BEST FAMILY ENTERTAINMENT EVENT UNVEILS MULTI MILLION DOLLAR FREE-WITH-ADMISSION LINEUP – INCLUDING THE RETURN OF THE ‘PNE FEATURE PAVILION’ Vancouver, B.C. – Since 1910 fairgoers from across BC and around the world have made the Fair at the PNE their end-of-summer tradition and British Columbia’s most popular ticketed event. For 2012, the Fair at the PNE is proud to unveil plans for the return of one of its most popular programs – the PNE Pavilion. “Having a walk-through exhibit was a big part of our history,” says PNE President and CEO Mike McDaniel. “For 2012 we’ve brought back the concept, with one of the most sought-after exhibit displays in the world – Star Trek – The Exhibition.” PNE TO HOST “STAR TREK – THE EXHIBITION” – FREE WITH ADMISSION TO THE 2012 FAIR Star Trek Pavilion 2012 marks the return of the PNE Feature Pavilion showcasing the new Star Trek exhibit brought in from Vienna, Austria. This expansive exhibit will take 3 weeks to set up and has a footprint of 20,000 square feet. The Pavilion harkens back to the days when the PNE was known for its incredible walk through exhibits. The Star Trek exhibit will take you through the bridge of the Starship Enterprise and feature a display of original costumes, masks and ship models. You will see firsthand the imagination, artistry, technology and meticulous craftsmanship that have made Star Trek the most enduring science fiction franchise in history. There will be multiple photo opportunities including Captain Kirk’s Chair, the Transporter Room or a picture with your favourite character in front of a green screen. -

Bay Area Cabaret Returns to San Francisco's Most Historic Showroom

BAY AREA CABARET RETURNS TO SAN FRANCISCO’S MOST HISTORIC SHOWROOM, THE FAIRMONT VENETIAN ROOM Presents Ninth Season of Nationally Renowned Vocalists Season opens October 28 with “Supremes” Legend Mary Wilson, continues with Broadway icon Tommy Tune, singer/actor Peter Gallagher, Broadway duo Marin Mazzie and Jason Danieley, actress/recording artist Elaine Paige, actress/singer Nellie McKay performing with Chanticleer, and a season finale Marvin Hamlisch Tribute. San Francisco, CA (September 14, 2012) --- Bay Area Cabaret, the local non-profit organization devoted to presenting audiences with top performers who expand the definition of cabaret, has announced its lineup for the 2012-2013 season. Opening the season Sunday, October 28, 2012 is Motown legend and founding member of “Supremes,” Mary Wilson, followed Sunday, November 11, 2012 by 9-time Tony Award winning singer/dancer/director/choreographer Tommy Tune, and December 9, 2012 by television, film, and Broadway star Peter Gallagher. The series continues in 2013 with “Broadway’s golden couple,” Marin Mazzie and Jason Danieley on February 17, 2013, “Britain’s first lady of musical theatre” Elaine Paige on March 1, 2013, and a performance by singer/actress Nellie McKay featuring San Francisco’s Grammy-winning a capella male chorus Chanticleer on March 23, 2013. Rounding out the season is a tribute to the late Marvin Hamlisch, with special guests to be announced, on June 2, 2013, which would have been the legendary composer’s 69th birthday, with special guests to be announced. After several seasons of presenting shows in a variety of elegant showrooms, Bay Area Cabaret found a permanent home two years ago when it was invited to reopen the Fairmont Hotel’s historic Venetian Room, which had been dark as an entertainment venue for over 21 years. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

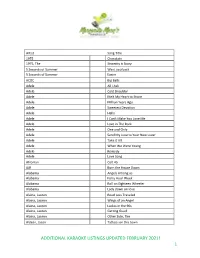

Additional Karaoke Listings Updated February 2021! 1

Artist Song Title 1975 Chocolate 1975, The Sincerity is Scary 5 Seconds of Summer Want you back 5 Seconds of Summer Easier ACDC Big Balls Adele All I Ask Adele Cold Shoulder Adele Melt My Heart to Stone Adele Million Years Ago Adele Sweetest Devotion Adele Hello Adele I Can't Make You Love Me Adele Love in The Dark Adele One and Only Adele Send My Love to Your New Lover Adele Take It All Adele When We Were Young Adele Remedy Adele Love Song Afroman Colt 45 AJR Burn the House Down Alabama Angels Among us Alabama Forty Hour Week Alabama Roll on Eighteen Wheeler Alabama Lady down on love Alaina, Lauren Road Less Traveled Alaina, Lauren Wings of an Angel Alaina, Lauren Ladies in the 90s Alaina, Lauren Getting Good Alaina, Lauren Other Side, The Aldean, Jason Tattoos on this town ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 1 Aldean, Jason Just Getting Started Aldean, Jason Lights Come On Aldean, Jason Little More Summertime, A Aldean, Jason This Plane Don't Go There Aldean, Jason Tonight Looks Good On You Aldean, Jason Gettin Warmed up Aldean, Jason Truth, The Aldean, Jason You make it easy Aldean, Jason Girl Like you Aldean, Jason Camouflage Hat Aldean, Jason We Back Aldean, Jason Rearview Town Aldean, Jason & Miranda Lambert Drowns The Whiskey Alice in Chains Man In The Box Alice in Chains No Excuses Alice in Chains Your Decision Alice in Chains Nutshell Alice in Chains Rooster Allan, Gary Every Storm (Runs Out of Rain) Allan, Gary Runaway Allen, Jimmie Best shot Anderson, John Swingin' Andress, Ingrid Lady Like Andress, Ingrid More Hearts Than Mine Angels and Airwaves Kiss & Tell Angston, Jon When it comes to loving you Animals, The Bring It On Home To Me Arctic Monkeys Do I Wanna Know Ariana Grande Breathin Arthur, James Say You Won't Let Go Arthur, James Naked Arthur, James Empty Space ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 2 Arthur, James Falling like the stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite the Stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite The Stars Ashanti Happy Ashanti Helpless (ft. -

Steve Clements Bio

STEVE CLEMENTS BIO For 40 plus years, Steve Clements has taught, trained, written for, directed and produced in all aspects of performance from corporate communications to speeches and events, national network broadcasts, video, and boardroom and courtroom presentations, as well as a multitude of experiences across his years as a Hollywood producer. Refining my presentation skills Now, working with executives in many Fortune 500 companies as was one of the best ways to oral communications consultant and media trainer, Steve distills increase my effectiveness with his focus into a basic philosophy: Find the best you and practice colleagues and customers. The it until it is second nature. Then utilize it for guaranteed success Executive Speak/Write team in every communications challenge. improved my speaking awareness and style. Their approach was Steve began honing this philosophy while teaching Television and very professional, detailed and Speech on college and secondary levels in New York City. In the easy to apply. Now I'm a more evenings, he performed as a stand-up comic at the legendary comfortable, confident and Improv and Catch a Rising Star, and appeared Off-Broadway with commanding speaker according the prestigious Roundabout Theatre Company. These experiences to my management team were the segue to his becoming a situation comedy writer in Los members. The improvement has Angeles for WELCOME BACK, KOTTER and THREE’S been remarkable. COMPANY, and a writer for the classic talk/variety series . Jamie Hillend, Director, DINAH!, starring Dinah Shore. Marketing Department, Appleton, Inc. Soon he became co-creator of a ground-breaking show for women, HOUR MAGAZINE. -

Show Programs

~ 52ND STREET PROJECT SHOW PROGRAMS 1996-2000 r JJj!J~f~Fffr!JFIEJ!fJE~JJf~fJ!iJrJtrJffffllj'friJfJj[IlJ'JiJJif~ i i fiiii 1 t!~~~~fi Jf~[fi~~~r~j (rjl 1 rjfi{Jij(fr; 1 !liirl~iJJ[~JJJf J Jl rJ I frJf' I j tlti I ''f '!j!Udfl r r.~~~.tJI i ~Hi 'fH '~ r !!'!f'il~ [ Uffllfr:pllfr!l(f[J'l!'Jlfl! U!! ~~frh:t- G 1 1 lr iJ!•f Hlih rfiJ aflfiJ'jrti lf!liJhi!rHdiHIIf!ff tl~![i!r~~ r ' ~ fjl r J' i r J i rf rf UJi[r'J f ~~ lfiJJ'J!(f r f I l f ji.EJ ,. J I f 1 t J r •Jl rrJ1 ~ l !JfJrf!f~!fl~lrJr!f'illfJ!rJrJfrJFf!fJI''IfJflf~'fJjl~rEJ!i 1 f,.JI f t'lflii'i!!'!'l!~f 1!r'jfrfij'~iffrfl' ~J!!1 f; 1 !~fJKri fi'IJaiJ,.Jr1 f; ~ r' u r r ~ Jf · ~ If rt ifl l• I ;f ' i t f,.fJittr 1J f t J ( .. t; J i' ' r r~ f JrlHrJ,.( ~~l[f!rfJ!rft:!fl[(lflrf~ff !jjl fjiJi'IJff'l!f'Jf!J!f!~{Jf !~jJljfj iUrf! ·• ih1;r r'H'i!r~ ;nr · ~ J' rr~1 H .. ~f'!~rr~tr 1 ift(JJ~r ; r ' i n Ef J i F r ~ 1ft, ' J F rJ~'fiU ~ t l f r IdJiuJ • • • • . • • •• • • i. • . • o · .. /J.. ., . {~~ • • • • ..f • . ;'* tOWS'. ' . e l =- '" ...... - ..-~ • • s • • • ..l • . •. • .. .. ..._• • ··.e: • : • = • .._:r ·. ·· .& ~ !r ......._ -teffAIITH • • ....~ --~·L~ ." - .- IS~~:~ ! . ·. • .. .. g c: I _: ·· ..!! .' • ... "A .. J!\aA.-!, I t C! 5' ·.