Six Weeks in Saratoga

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Welcometothe

9 welcome to the ® CHAMPIONS AVENUE 8 BIG BARN ROAD JAY TRUMP ROAD 7 1 Visitor Center Gift Shop 5 Wrigley Media Theatre 4 6 2 International Museum of the Horse SGT RECKLESS 3 American Saddlebred Museum 4 Kids Barn 5 Horse Drawn Trolley Tours 6 Mounted Police Barn Breeds Barn 2 7 3 8 Big Barn 9 Hall of Champions 10 Iron Works Café (Temporarily Closed) 10a High Horizons Food Truck (Open 10am-3pm) 11 Playground 10a SECRETARIAT PARKING 12 Horseback Trail Rides & Pony Rides 1 (Reserve in Visitor Center) 10 11 12 DAILY SCHEDULE MAN O’ WAR 9-10 am Grooming at Barns 7 8 10:00 am Horse Drawn Trolley 5 For Emergencies Call Mounted Police 10:30 am Hall of Champions Show 9 859-509-1450 11:00 am Parade of Breeds Show 7 Equestrian competitions are temporarily closed to spectators. am Big Barn Stall-Side Chat 8 11:45 Enjoy your visit safely! Smoking is prohibited in Barns and Buildings. 1:15 pm Hall of Champions Show 9 Please stand a horse length 2:00 pm Parade of Breeds Show 7 4089 Iron Works Parkway, apart from others. Follow Us! Lexington, Kentucky 40511 2:45 pm Horse Drawn Trolley 5 Masks are required 800-678-8813 in buildings and barns. 3:30 pm Derby Winner Nightcap 9 KyHorsePark.com #KYHORSEPARK KENTUCKY HORSE PARK DAILY SCHEDULE EXPLORE EQUINE HISTORY OPEN WEDNESDAY–SUNDAY, 9 AM TO 5 PM Morning Grooming 7 8 9-10 am Kick off your visit at the Breeds Barn and Big Barn to see the KHP equine team grooming horses and International Museum of the Horse preparing for the day! With over 60,000 square feet, IMH is dedicated Horse Drawn Trolley 5 to the history of the horse and its unique relationship with humans through time. -

Greatest Show in Racing by Ray Paulick

November 2, 2015 www.PaulickReport.com SPECIAL Greatest Show in Racing By Ray Paulick Let me start by saying that I never met a Breeders’ Cup I Horse of the Year was likely settled with most Eclipse Award didn’t like – and I’ve been to 28 of them. Some years have voters when American Pharoah became the first horse to win been better than others, both in the competition on the race- the Triple Crown since Affirmed in 1978. The only horse with track and the customer service delivered to the participants any chance to overtake him was the two-time champion mare and paying customers in the grandstand. Beholder, who ultimately was scratched from the Classic after a post-gallop endoscopic examination showed she had bled. Having said that, I loved almost everything about the “home- coming” Breeders’ Cup at Keeneland on Friday and Saturday. With his demonstration of complete superiority in the Classic, In a word, it was spectacular. There was one outstanding per- American Pharoah will be the unanimous choice for Horse of formance after another on the Keeneland dirt and turf, and the Year. the management, staff and outside security, traffic control and customer service team representing Keeneland and Breeders’ At the 2014 Keeneland September Sale, I ran into Fox Hill Cup were incredibly organized and efficient in helping put on the Farm’s Rick Porter, who mentioned that he was going to send Greatest Show in Racing. some young horses out to California for the first time. Continued on Page 5 American Pharoah’s overpowering performance in the Classic gave the 50,155 fans in attendance on Saturday something to tell their children and grandchildren. -

Funny Cide's Epic Kentucky Derby Victory Is Ten Years

Funny Cide’s Epic Kentucky Derby Victory is Ten Years Old By Bill Heller Can it be ten years since a three-year-old gelding named Funny Cide, and a yellow school bus carrying a group of high school friends who owned him, rearranged the racing industry’s position on New York- breds? “I don’t believe it,” his retired Hall of Fame jockey Jose Santos said Tuesday. “It went by too fast.” Funny Cide’s trainer, Barclay Tagg, agreed: “I do have trouble believing that.” Asked what’s the first thing that comes to his mind when someone asks him about Funny Cide, Jose said, “That he was the best three-year-old in my racing career.” These days, Jose has a new career running a feed company, Instride International, which began operating in 2012 and now serves three Florida tracks: Calder, Gulfstream Park and Palm Meadows. “Basically, I’m running the whole thing,” Jose said. “I’ve been selling to the trainers. They are friends of mine.” His client list includes a bunch of New York trainers who winter in Florida, including Todd Pletcher, John Kimmel, Linda Rice, Rick Violette and John Terranova. Funny Cide, a son of Distorted Humor out of Belle’s Good Cide by Slewacide, was bred by WinStar Farm and foaled at Joe and Anne McMahon’s Thoroughbred farm just outside Saratoga Springs. He was originally purchased for $22,000 before Tagg bought him for $75,000 for Sackatoga Stable, an entity formed when several old friends got together for a Memorial Day barbecue in their home town of Sackets Harbor. -

JESS's DREAM Dkb/Br, 2012

Entered Stud in 2017 JESS’S DREAM dkb/br, 2012 Dosage (6-6-7-1-0); DI: 3.44; CD: 0.85 See gray pages—Polynesian RACE RECORD Mr. Prospector, 1970 Raise a Native, by Native Dancer Age Starts 1st 2nd 3rd Earned 14s, BTW, $112,171 Smart Strike, 1992 1,178 f, 182 BTW, 3.91 AEI Gold Digger, by Nashua 2 0 0 0 0 — 8s, BTW, $337,376 3 1 1 0 0 $49,800 1,546 f, 135 BTW, 2.10 AEI Classy 'n Smart, 1981 Smarten, by Cyane 9s, BTW, $303,222 Totals 1 1 0 0 $49,800 Curlin, ch, 2004 16s, BTW, $10,501,800 9 f, 5 r, 5 w, 4 BTW No Class, by Nodouble Won At 3 777 f, 63 BTW, 2.37 AEI Deputy Minister, 1979 Vice Regent, by Northern Dancer A maiden special weight race at Sar ($83,000, 9f in 7.60 AWD 22s, BTW, $696,964 1:49.06, dftg. Securitiz, Godrevy, All Rise, Captain Sherriff's Deputy, 1994 1,142 f, 90 BTW, 2.52 AEI Mint Copy, by Bunty's Flight Unraced Tim, Sharm, Prodigal). 8 f, 6 r, 4 w, 1 BTW Barbarika, 1985 Bates Motel, by Sir Ivor 16s, BTW, $347,253 SIRE LINE 13 f, 10 r, 5 w War Exchange, by Wise Exchange Jess’s Dream is by CURLIN, black-type stakes winner of 11 races, $10,501,800, Horse of the Year twice, El Prado, 1989 Sadler's Wells, by Northern Dancer 9s, BTW, $275,231 champion 3yo colt, and older male in USA, champion Medaglia d'Oro, 1999 988 f, 83 BTW, 1.95 AEI Lady Capulet, by Sir Ivor older male in UAE, Preakness S (G1), Emirates Airline 17s, BTW, $5,754,720 Dubai World Cup (G1 in UAE), Breeders’ Cup Classic 1,826 f, 135 BTW, 1.96 AEI Cappucino Bay, 1989 Bailjumper, by Damascus Rachel Alexandra, b, 2006 24s, BTW, $164,433 Powered by Dodge (G1), Stephen Foster H (G1), Jockey 9 f, 7 r, 5 w, 2 BTW Dubbed In, by Silent Screen Club Gold Cup S (G1) twice, Woodward S (G1), 19s, BTW, $3,506,730 2 f, 2 r, 2 w, 1 BTW Arkansas Derby (G2), Rebel S (G3), 2nd Belmont S (G1), Roar, 1993 Forty Niner, by Mr. -

Horsing Around Behind the Scenes Is

Horsing around behind-the-scenes "Jest ''part of racing season fun What were the odds the 2019 Kentucky Derby's Win-Place-Show trainers (Country Horse, FIRST; William "Bill" Mott; Code of Honor, SECOND, trainer Shug McGaughey; Tacitus, THIRD, again Mott) would share the same dentist in a small upstate New York village? Too easy? Okay, then. Let's kick it up a notch with more Thoroughbred racing trivia about what some have nicknamed Saratoga County's Trifecta Dental Spa. What were the odds that in addition to Mott and McGaughey, the Ballston Spa practice of Doctor of Dental Surgery Thomas Pray would also include much celebrated Kentucky Derby winning trainers Barclay Tagg (Funny Cide, 2003) and Nick Zito (Strike the Gold, 1991 and Go for Gin, 1994)? While it's a sure bet we at Legacies Unlimited don't yet have definitive answers to these questions, we hope reading the above will spark unbridled enthusiasm in seeking out complimentary copies of the exquisite July-August 2019 edition of Simply Saratoga magazine. Among the articles found within the current 196-page issue of the glossy periodical is one by Legacies Unlimited co-founder Ann Hauprich titled "Horsing around with Saratoga's unofficial track dentist Tom Pray." The richly illustrated feature documents how the ingenuity and integrity which Dentist Thomas Pray and staff members Joy Soriano, Taylor Joyce, Pray demonstrated along the backstretch three decades ago led his practice (then Mel Curry, Bre McCoy and Susie Joyce couldn't resist horsing around still cutting its baby teeth) to become a dental home turf for hundreds of patients near the tail end of a portrait session with Donna Martin at Village Photo in Ballston Spa, NY Vickie Yanagihara subsequently linked to Saratoga's thoroughbred racing industry, including world renowned captured the action when National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame Hall trainer Nick Zito and equine artist R.C. -

138904 02 Classic.Pdf

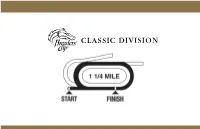

breeders’ cup CLASSIC BREEDERs’ Cup CLASSIC (GR. I) 30th Running Santa Anita Park $5,000,000 Guaranteed FOR THREE-YEAR-OLDS & UPWARD ONE MILE AND ONE-QUARTER Northern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 122 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs.; Southern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 117 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs. All Fillies and Mares allowed 3 lbs. Guaranteed $5 million purse including travel awards, of which 55% of all monies to the owner of the winner, 18% to second, 10% to third, 6% to fourth and 3% to fifth; plus travel awards to starters not based in California. The maximum number of starters for the Breeders’ Cup Classic will be limited to fourteen (14). If more than fourteen (14) horses pre-enter, selection will be determined by a combination of Breeders’ Cup Challenge winners, Graded Stakes Dirt points and the Breeders’ Cup Racing Secretaries and Directors panel. Please refer to the 2013 Breeders’ Cup World Championships Horsemen’s Information Guide (available upon request) for more information. Nominated Horses Breeders’ Cup Racing Office Pre-Entry Fee: 1% of purse Santa Anita Park Entry Fee: 1% of purse 285 W. Huntington Dr. Arcadia, CA 91007 Phone: (859) 514-9422 To Be Run Saturday, November 2, 2013 Fax: (859) 514-9432 Pre-Entries Close Monday, October 21, 2013 E-mail: [email protected] Pre-entries for the Breeders' Cup Classic (G1) Horse Owner Trainer Declaration of War Mrs. John Magnier, Michael Tabor, Derrick Smith & Joseph Allen Aidan P. O'Brien B.c.4 War Front - Tempo West by Rahy - Bred in Kentucky by Joseph Allen Flat Out Preston Stables, LLC William I. -

HEADLINE NEWS • 5/3/09 • PAGE 2 of 18

HEADLINE THREE CHIMNEYS NEWS The Idea is Excellence. For information about TDN, Three Chimneys Congratulates call 732-747-8060. Calvin Borel on His Oaks/Derby Double! www.thoroughbreddailynews.com SUNDAY, MAY 3, 2009 TDN Feature Presentation REVENGE WILL HAVE TO WAIT Morning-line favorite I Want Revenge (Stephen Got GRADE 1 KENTUCKY DERBY Even) was scratched from the GI Kentucky Derby after heat was detected in his left front ankle. AWe detected a little pressure and a touch of heat in the left front ankle,@ trainer Jeff Mullins explained. AWe jogged him up and down the asphalt to check for soundness, and he actually jogged pretty well. We flexed the ankle and A DELIGHTFUL DERBY DAY! he gave to the flexing of the ankle. By that time, Dr. SMART STRIKE: BDM. SIRE OF MINE THAT BIRD - 1ST KENTUCKY DERBY Foster [Northrop] showed up. He jogged him again and LEMON DROP KID: BRONZE CANNON-G2W & COSMONAUT-G3W A.P. INDY: FLASHING-G3W he jogged fairly good. Dr. Foster flexed the ankle and MINESHAFT: MINER’S ESCAPE - LISTED STAKES WINNER he gave to the flexion again.@ The veterinarian added, AOn the digital X-rays, I=m not seeing any bone lesion at THE ULTIMATE RAILBIRD all. It X-rays really pristine, so I do think it=s more soft One day after piloting 1-5 Rachel Alexandra (Medaglia tissue at this point. Ultrasound, which is basically an d=Oro) to a dominant victory in X-ray on soft tissue, I=m not seeing a lesion either. So the GI Kentucky Oaks, jockey further diagnostics will be done.@ Cont. -

HORSES, KENTUCKY DERBY (1875-2019) Kentucky Derby

HORSES, KENTUCKY DERBY (1875-2019) Kentucky Derby Winners, Alphabetically (1875-2019) HORSE YEAR HORSE YEAR Affirmed 1978 Kauai King 1966 Agile 1905 Kingman 1891 Alan-a-Dale 1902 Lawrin 1938 Always Dreaming 2017 Leonatus 1883 Alysheba 1987 Lieut. Gibson 1900 American Pharoah 2015 Lil E. Tee 1992 Animal Kingdom 2011 Lookout 1893 Apollo (g) 1882 Lord Murphy 1879 Aristides 1875 Lucky Debonair 1965 Assault 1946 Macbeth II (g) 1888 Azra 1892 Majestic Prince 1969 Baden-Baden 1877 Manuel 1899 Barbaro 2006 Meridian 1911 Behave Yourself 1921 Middleground 1950 Ben Ali 1886 Mine That Bird 2009 Ben Brush 1896 Monarchos 2001 Big Brown 2008 Montrose 1887 Black Gold 1924 Morvich 1922 Bold Forbes 1976 Needles 1956 Bold Venture 1936 Northern Dancer-CAN 1964 Brokers Tip 1933 Nyquist 2016 Bubbling Over 1926 Old Rosebud (g) 1914 Buchanan 1884 Omaha 1935 Burgoo King 1932 Omar Khayyam-GB 1917 California Chrome 2014 Orb 2013 Cannonade 1974 Paul Jones (g) 1920 Canonero II 1971 Pensive 1944 Carry Back 1961 Pink Star 1907 Cavalcade 1934 Plaudit 1898 Chant 1894 Pleasant Colony 1981 Charismatic 1999 Ponder 1949 Chateaugay 1963 Proud Clarion 1967 Citation 1948 Real Quiet 1998 Clyde Van Dusen (g) 1929 Regret (f) 1915 Count Fleet 1943 Reigh Count 1928 Count Turf 1951 Riley 1890 Country House 2019 Riva Ridge 1972 Dark Star 1953 Sea Hero 1993 Day Star 1878 Seattle Slew 1977 Decidedly 1962 Secretariat 1973 Determine 1954 Shut Out 1942 Donau 1910 Silver Charm 1997 Donerail 1913 Sir Barton 1919 Dust Commander 1970 Sir Huon 1906 Elwood 1904 Smarty Jones 2004 Exterminator -

Horse Racing

Horse Racing From the publisher of: EQUUS Dressage Today Horse & Rider Practical Horseman Arabian Horse World Search Home :: Classifieds :: Shopping :: Forums/Chat :: Subscribe :: News & Results :: Giveaway Winners Newsletter Sign-Up Racing Win It! Weekly tips and articles Sponsor this topic! Win Reichert on horse care, training Celebration VIP Passes! and more >> Speed is of the essence in this sport that pits the fastest equines against each Growing Up With Horses other. Here, find stories on Thoroughbreds, Standardbreds and other racing Kids' Essay Contest TOPICS breeds. Enter JPC Equestrian's Home $10,000 Giveaway On the 30th Anniversary of About EquiSearch Win an Irish Riding Trip Art & Graphics Ruffian's Last Race & More! Associations Lyn Lifshin reflects on the life of the super racehorse Ruffian who died Breeds during a match race against Foolish Where To Shop! Horse Care Pleasure on July 6, 1975. Columnists Equestrian Collections Community The Superstore for Horse Equine Education and Rider EquiWire News/Results The Equine Collection Farm and Stable Horse books and DVDs Kentucky Horse Park Glossary Horsey Humor Horse Racing News & Results Gift Shop Junior Horse Lovers Gifts and Collectibles Find A Tack Shop Lifestyle More Racing Articles Magazines Shoemaker Remembered Beginning Adult Rider Buyers' Guides October 16, 2003 -- Bill Shoemaker died October 12 at Quiz the age of 72. His fellow jockeys share their memories. Insurance Rescue/Welfare Tack & Apparel Seabiscuit Trailers Shopping More Buyers' Guides Horse Sports Endurance Seabiscuit: An American Legend. Steeplechase News, photos, quotes and more on the Depression-era racing star and his Olympics connections. To visit EquiSearch's special section on Seabiscuit click here. -

BIRDSTONE B, 2001 Height 15.3 Dosage (7-8-9-0-2); DI: 3.00; CD: 0.69 See Gray Pages—Polynesian RACE and (STAKES) RECORD Fappiano, 1977 Mr

BIRDSTONE b, 2001 height 15.3 Dosage (7-8-9-0-2); DI: 3.00; CD: 0.69 See gray pages—Polynesian RACE AND (STAKES) RECORD Fappiano, 1977 Mr. Prospector, by Raise a Native Age Starts 1st 2nd 3rd Earned 17s, SW, $370,213 2 3 2(1) 0 0 $339,000 Unbridled, 1987 410 f, 48 SW, 4.40 AEI Killaloe, by Dr. Fager 3 6 3(2) 0 0 $1,236,600 24s, SW, $4,489,475 566 f, 49 SW, 2.65 AEI Gana Facil, 1981 Le Fabuleux, by Wild Risk Totals 9 5(3) 0 0 $1,575,600 Grindstone, dkb/br, 1993 19s, wnr, $85,100 7 f, 6 r, 5 w, 2 SW Charedi, by In Reality Won At 2 6s, SW, $1,224,510 Champagne S (gr. I, $500,000, 8.5f in 1:44.05, by 554 f, 21 SW, 1.12 AEI Drone, 1966 Sir Gaylord, by Turn-to 2½, dftg. Chapel Royal, Dashboard Drummer, 7.38 AWD 4s, wnr, $12,825 Paddington, Notorious Rogue, Read the Footnotes, Buzz My Bell, 1981 592 f, 54 SW, 2.23 AEI Cap and Bells, by Tom Fool 13s, SW, $223,295 Midnight Express). 11 f, 10 r, 8 w, 3 SW Chateaupavia, 1966 Chateaugay, by Swaps A maiden special weight race at Sar ($45,000, 6f in 42s, wnr, $36,280 1:10.32, by 12½, dftg. Bold Love, Hornshope, etc.). 12 f, 11 r, 8 w, 1 SW Glenpavia, by Pavot Won At 3 Northern Dancer, 1961 Nearctic, by Nearco Belmont S (gr. -

Congressional Record—Senate S6143

May 15, 2007 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S6143 critical change—it’s the U.S.-China SUBMITTED RESOLUTIONS Spun in the stretch and draw away to a 21⁄4- Commission and the GAO as well. length victory; When my amendment stalled over a Whereas the victory was Calvin Borel’s SENATE RESOLUTION 199—CALL- first in the Kentucky Derby; committee jurisdictional point, on Sep- ING FOR THE IMMEDIATE AND Whereas Calvin Borel was born on Novem- tember 29, 2005, I chose to introduce UNCONDITIONAL RELEASE OF ber 7, 1966, in St. Martinsville, Louisiana; the changes as a stand-alone bill, the DR. HALEH ESFANDIARI Whereas Calvin Borel hails from South Foreign Investment Security Act of Louisiana, the heart of Cajun Country, fa- 2005, S. 1797, which was referred to the Mr. SMITH (for himself and Mrs. mous for its production of many top jockeys Banking Committee. That bill was the CLINTON) submitted the following reso- during the last 20 years; and first bill introduced in recent years on lution; which was referred to the Com- Whereas Calvin Borel’s victory in the 133rd this topic. mittee on Foreign Relations. running of the Kentucky Derby solidifies his place in a tradition of Louisiana jockeys who S. RES. 199 Later the Banking Committee held a have won the Kentucky Derby, such as Eric hearing on the GAO report, and I testi- Whereas Dr. Haleh Esfandiari is one of the Guerin (1947), Edward Delahoussaye (1982, fied before them on October 20, 2005, at United States’s most distinguished analysts 1983), Craig Perret (1990), and Kent that hearing. -

MJC Media Guide

2021 MEDIA GUIDE 2021 PIMLICO/LAUREL MEDIA GUIDE Table of Contents Staff Directory & Bios . 2-4 Maryland Jockey Club History . 5-22 2020 In Review . 23-27 Trainers . 28-54 Jockeys . 55-74 Graded Stakes Races . 75-92 Maryland Million . 91-92 Credits Racing Dates Editor LAUREL PARK . January 1 - March 21 David Joseph LAUREL PARK . April 8 - May 2 Phil Janack PIMLICO . May 6 - May 31 LAUREL PARK . .. June 4 - August 22 Contributors Clayton Beck LAUREL PARK . .. September 10 - December 31 Photographs Jim McCue Special Events Jim Duley BLACK-EYED SUSAN DAY . Friday, May 14, 2021 Matt Ryb PREAKNESS DAY . Saturday, May 15, 2021 (Cover photo) MARYLAND MILLION DAY . Saturday, October 23, 2021 Racing dates are subject to change . Media Relations Contacts 301-725-0400 Statistics and charts provided by Equibase and The Daily David Joseph, x5461 Racing Form . Copyright © 2017 Vice President of Communications/Media reproduced with permission of copyright owners . Dave Rodman, Track Announcer x5530 Keith Feustle, Handicapper x5541 Jim McCue, Track Photographer x5529 Mission Statement The Maryland Jockey Club is dedicated to presenting the great sport of Thoroughbred racing as the centerpiece of a high-quality entertainment experience providing fun and excitement in an inviting and friendly atmosphere for people of all ages . 1 THE MARYLAND JOCKEY CLUB Laurel Racing Assoc. Inc. • P.O. Box 130 •Laurel, Maryland 20725 301-725-0400 • www.laurelpark.com EXECUTIVE OFFICIALS STATE OF MARYLAND Sal Sinatra President and General Manager Lawrence J. Hogan, Jr., Governor Douglas J. Illig Senior Vice President and Chief Financial Officer Tim Luzius Senior Vice President and Assistant General Manager Boyd K.