Do Boundaries Inhibit the Growth of New Psychologies? Lois Holzman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Let's Pretend

Solving the Education Crisis in America: A Special Report LET’S PRETEND by Fred Newman, Ph.D. and Lenora Fulani, Ph.D. January 2011 LET’S PRETEND 1. Here is an idea for solving the education crisis in America. What if all the kids currently failing in school pretended to be good learners? What if all the adults – teachers, principals, administrators, parents – played along and pretended that the kids were school achievers, heading for college? What if this national “ensemble” pretended this was the case day after day, classroom after classroom, school district after school district? We believe that if such a national “performance” were created, the education crisis in America would be over. Children, having developed the capacity to pretend to be who Learning takes they are not, i.e., good learners, also develop the capacity to become the thing they are pretending to be. And, thus, if we could all together assist poor and minority kids in development, pretending that they are classroom achievers, they could choose to become that. and if kids are Is this idea as ridiculous as it might seem at first glance? At the risk of seeming ridiculous, our answer is an emphatic “no.” Because the most innovative researchers and practitioners underdeveloped, have come to discover that pretending, or “creatively imitating,” or performing in social contexts, is how human development is produced.1 Harnessing the uniquely human they do not capacity to perform someone or something we are not, underachieving kids can pretend their way to growth. We have seen the repeated success of this approach – not only in our become after-school programs at the All Stars Project, but also (perhaps unknowingly) in school settings now applauded as the most successful interventions into the “achievement gap” learners. -

LOIS HOLZMAN East Side Institute for Group and Short Term

LOIS HOLZMAN East Side Institute for Group and Short Term Psychotherapy 920 Broadway, 14th floor, New York NY 10010 212.941.8906 (phone) 212.941.0511 (fax) [email protected] www.loisholzman.net and www.eastsideinstitute.org EDUCATION Ph.D. in Developmental Psychology Columbia University, 1977 Graduate Study in Linguistics Columbia University and Brown University, 1968-1970 Bachelor of Arts, English Rhode Island College, 1967 RESEARCH AND TEACHING EXPERIENCE Director, 2001-present East Side Institute for Group and Short Term Psychotherapy, New York NY (Director of Research & Educational Programs, 1989-2001) Initiated Research Projects & Gatherings • 2008, International Conference—Performing the World 2008 • 2007, International Conference—Performing the World 4: The Performance of Community and the Community of Performance • 2005, International Conference—Performing the World 3: The Performance of Creativity and the Creativity of Performance • 2005, Conference: Vygotsky at Work and Play in Educational, Therapeutic and Organizational Setttings • 2003, International Conference—Performing the World 2: The Second International Conference Exploring the Potential of Performance for Personal, Organizational and Social-Cultural Change. • 2002, Young People Learn by Studying Themselves: The All Stars Talent Show in Action (Youth participatory study of youth development-supplemental education program). Funded by The Virginia Wellington Cabot Foundation. • 2002, Weekend Retreat for Medical Professionals: A Dialogue on Changing the Culture of Healthcare. • 2001, International Conference—Performing the World: Communication, Improvisation and Societal Practice • 2001, Weekend Retreat for Sex Education/Teen Pregnancy Prevention Professionals. Funded by Cabot Family Charitable Trust. • 2000, Growing Up Performed (Performance-based outside-of-school program to promote the social and emotional development of young people who have experienced abuse in their lives). -

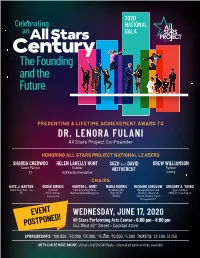

Century the Founding and the Future

2020 Celebrating NATIONAL an GALA All Stars Century The Founding and the Future PRESENTING A LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARD TO DR. LENORA FULANI All Stars Project Co-Founder HONORING ALL STARS PROJECT NATIONAL LEADERS SHARDA CHERWOO HELEN LAKELLY HUNT SUZU and DAVID DREW WILLIAMSON Senior Partner Founder NEITHERCUT Partner EY HLH Family Foundation Cooley CHAIRS KATE J. BARTON DEREK DIRISIO HUNTER L. HUNT MARIA MORRIS RICHARD SOKOLOW GREGORY A. TOSKO Global Vice Chair - Tax President Chief Executive Officer Board Director Managing Director and Vice Chairman EY PSEG Services Hunt Consolidated Energy, LLC Retired EVP Director of Research CBRE Tri-State Region Corporation MetLife Davidson Kempner Capital Management, LP EVENT WEDNESDAY, JUNE 17, 2020 All Stars Performing Arts Center • 6:00 pm - 8:00 pm POSTPONED! 543 West 42nd Street • Cocktail Attire SPONSORSHIPS: $100,000, $50,000, $25,000, $15,000, $10,000, $5,000 TICKETS: $2,500, $1,250 GIFTS CAN BE MADE ONLINE: allstars.org/2020ASPgala • Journal ad sponsorships available Celebrating anAll Stars Century The Founding 2020 NATIONAL and the Future GALA A message from our CEO GABRIELLE L. KURLANDER CELEBRATING AN ALL STARS CENTURY THE FOUNDING AND THE FUTURE “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world: indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.” – Margaret Mead The All Stars Project has always been visionary about creating community and connecting young people who are growing up poor to the mainstream of American life. As we look ahead, I am proud to say that 50 years of painstaking and intentional organizing has brought forth a powerful new movement for human development, focused on youth and committed to engaging poverty across our country in dynamic new ways. -

1 How Much of a Loss Is the Loss of Self

How Much of a Loss is the Loss of Self? Understanding Vygotsky from a Social Therapeutic Perspective and Vice Versa1 Lois Holzman East Side Institute for Group and Short Term Psychotherapy www.eastsideinstitute.org Should I be talking about myself I who Who am I talking about when I talk about myself I Who is that Heiner Müller, “Landscape with Argonauts” Mr. Descartes Who do you think you are? What you think Is what you be Cogito ergo sum Sounds okay But said to whom? Fred Newman, “Off-Broadway Melodies of 1592” One of my favorite quotations attributed to Lev Vygotsky is the following: “A revolution solves only those tasks raised by history: this proposition holds true equally for revolution in general and for aspects of social and cultural life” (Vygotsky, quoted in Levitan, 1982, inside front cover). During Vygotsky’s lifetime, history had raised some monumental tasks, which he devoted his life to addressing. One of them was the crisis in psychology. In our lifetime as well, history is raising monumental tasks. One of them is the crisis in psychology. Psychology’s crisis is a crisis in development: have the world’s people stopped developing—emotionally-socially-intellectually-culturally-morally— and, if so, is there anything to do about it? Has psychology stopped discovering anything 1 that might be useful to human beings in transforming how we live (together)? My formal training was as a developmental psychologist, but I prefer the term developmentalist, as a way to refer to research and practice to reinitiate human development, which I take to be an historically specific sociocultural need. -

Into the Study of Language Acquisition

CITATION: Bloom, L. (1997). Putting the child (back) into the study of language acquisition. Address on Receiving the G. Stanley Hall Award for Distinguished Contribution to Developmental Psychology from the American Psychological Association, Division 7, Chicago. Putting the Child (Back) into the Study of Language Acquisition Lois Bloom Teachers College, Columbia University Abstract A cold wind has blown down from the Northeast, casting a chill on the study of language acquisition: In research driven by adult linguistic theory and, in particular, the linguistic theories of MIT, it is a device that acquires a language, not a child, and language is separate from the rest of cognition and human development. The purpose of my presentation will be to 'put the child back into the study of language acquisition' by showing how language is integrated with other behaviors as the development of language connects with other aspects of children's development. I begin with a brief review of how the focus shifted from a child to a device in the last generation of language acquisition research and theory. I then present a developmental model of language acquisition based on the young child's intentionality (Bloom, 1993a, 1997, Bloom & Beckwith, 1987) and use the model to interpret results from some current research. The research findings show how children's language connects with their affective, social, and other cognitive behaviors--both in the real time of everyday events and the developmental time encompassed by the 2nd year of life. The conclusions are that language is not special and is not separate from the rest of a child's life and development. -

Activity and Performance (And Their Discourses) in Social Therapeutic Method

Draft Chapter to appear (2011) in Discursive Perspectives in Therapeutic Practice edited by Tom Strong & Andrew Lock, Oxford University Press. Activity and Performance (and their Discourses) in Social Therapeutic Method Lois Holzman and Fred Newman1 East Side Institute for Group and Short Term Psychotherapy, New York NY As collaborators on the development of social therapy, Fred Newman and Lois Holzman bring different things to the task. Newman was trained as a philosopher, originated social therapy and practices it, and is a playwright and director. Holzman was trained as a developmental psychologist and psycholinguist, and practices as a teacher, trainer and researcher. Both of us write on social therapy theory/practice, sometimes together and at other times separately. When we write together, we sometimes speak in one voice and at other times in two (or perhaps more). For this chapter we decided to preserve our two voices. After a brief historical and conceptual overview of our approach, the chapter is organized as three discourses on social therapy as performance. In Discourse 1, we together introduce that topic in relation to the practice of social therapy, the teaching of it, and directing plays. Discourse 2 was written by Holzman who takes a developmental psychologist (Vygotskian) perspective. Discourse 3, written by Newman, is a concise philosophical-political characterization of social therapy’s performance modality. Overview 1 Contact Information: lholzman@east sideinstitute.org, [email protected]. See also: www.eastsideinstitute.org, loisholzman.org, www.frednewmanphd.com. 1 Social therapy (or the broader practice/theory of social therapeutics) is an approach to human development and learning at the leading edge of the critical and postmodernist movements in psychology. -

PTW Presenters-Web

Samuel Beckett and the art of Eduard Vuillard; embrace their bravado and share their personal choreographer of Manscapes, a movement piece stories. Lola is also the director of the Courageous Presenters for awkward men; singing with Nexus, a concert Kids Performance Troupe, a group of bereaved association that brings sacred music to life; acting teenagers that performs a show about grief and Judith Albert is a senior managing director at New York City and the Northeast. After receiving the clones of Hitler in the film, The Boys from loss that tours the middle and high schools in the Bear, Stearns & Co., where she is responsible for his Ph.D. from Cornell University, Hal was Artist- Brazil; and touring the Northeast in Slim Eugene area. She teaches a women’s personal professional development and strategic initiatives in-Residence in 1997 at Teatro Milagro, a Goodbody's one man show about the human theater class called “Get down with your sweet in the Investment Banking department. For much Latino/Caribeno dance/theater company in anatomy. self” Lola is a long time member of Eugene of her career Judith focused on Latin America: in Portland OR. He was awarded a Rockefeller Playback Theater. She is the director of Imagine Annica Bray is president of WebBrand AB, a financial services at Bear Stearns, Violy, Byorum & Postdoctoral Fellowship in the Humanities and That Summer Adventures, creative arts and consulting firm based in Skelleftea in the north Partners and J.P. Morgan; in corporate law at the Hermandad Prize by the Instituto de Puerto performance camps for kids from ages of 7 to 11. -

Postdisciplinary Knowledge

6 Knowledge as play Centring on what matters Tomas Pernecky and Lois Holzman This is a dialogue between Tomas Pernecky and Lois Holzman about ac- ademia, learning, education, Lev Vygotsky and spaces in which we live and work as researchers, students, professionals and intellectuals. It seeks to uncover the developmental and non-developmental sides of knowledge through the discussion of topics such as academic integrity, activism, crea- tivity, epistemic posturing, social constructionism, social therapeutics and performance-based approaches to education and therapy. The notion of knowledge-as-play emerges subtly but with force as a recognition that the quest to know is intimately human, and therefore inseparable from our in- teraction with other humans and the world, part of our ways of being, doing and becoming – and always something we can play with. Thoughts on education, play and culture TOMAS: I suppose an appropriate way to begin this dialogue on knowledge- as-play is to invite you to play with me. I am interested in exchanging ideas about this topic because I see playfulness and creativity as some- thing that is closely connected with knowledge. Do you want to play? LOIS: What a lovely and challenging offer! Yes, I want to play! Knowing makes our brains heavy. Playing makes them lighter. Playing with knowing – what does that do? We cannot know, but we can play! TOMAS: Your mention of heavy brains reminds me of the education I expe- rienced earlier in my life. It was built around memorising – memorising dates, memorising names, memorising key historical events, memoris- ing rivers and geological formations, memorising chemical formulas, memorising works in literature and so forth. -

Practicing a Psychology That Builds Community

Practicing a Psychology That Builds Community Lois Holzman, Ph. D. East Side Institute for Short Term Psychotherapy [1] I was trained as a developmental psychologist, but over the years I've become uncomfortable with that label. It's too disciplinary for my taste; it makes a false separation between development and other human psychological functioning; and it's based on a stagist understanding of human life that I don't agree with. [2] So, I prefer to think of myself as a developmentalist, to convey both the attitude and activity of someone who supports people to utilize their creative capacities to grow and develop throughout their lifetimes. My transformation, if you will, from developmental psychologist to developmentalist has proceeded hand in glove with my training and experience as a community organizer. To me, supporting people to grow and develop is inseparable from building community. The work I have been involved in for the last 25 years is the creating of a community psychology of a new and different sort. It's a psychology that builds community and simultaneously studies its own community building process. What I want to share with you today is some of what that activity looks like and its history and methodological base. Whatever uses this methodology might have for enriching community psychology I hope that we can discover together. I suppose a good place to begin is by sharing what I mean by community. To me, community does not exist "out there" waiting to be studied; in our current alienated, fragmented and destabilized culture, community is just too difficult to sustain and is, at best, ephemeral. -

Changing the Script for Youth Development: an Evaluation of the All Stars Talent Show Network and the Joseph A

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 478 409 UD 035 813 AUTHOR Gordon, Edmund W.; Bowman, Carol Bonilla; Mejia, Brenda X. TITLE Changing the Script for Youth Development: An Evaluation of the All Stars Talent Show Network and the Joseph A. Forgione Development School for Youth. INSTITUTION Columbia Univ., New York, NY. Inst. for Urban and Minority Education. PUB DATE 2003-06-00 NOTE 124p. AVAILABLE FROM Institute for Urban and Minority Education, Teachers College, Columbia University, Box 75, 525 West 120th Street, New York, NY 10027. Tel: 212-678-3780; Web site: http://iume.tc.columbia.edu. PUB TYPE Reports Evaluative (142) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adolescents; *Career Development; Drama; *Leadership Training; *Supplementary Education ;*Talent Development; Theater Arts; *Youth Programs IDENTIFIERS *Talent Development Framework; *Youth Development Model ABSTRACT This evaluation describes two supplementary education interventions: the All Stars Talent Show Network (ASTSN) and the Joseph A. Forgione Development School for Youth (DSY). The ASTSN is a 19-year-old program that provides youth age 5-25 with opportunities to produce and participate in talent shows, thus creating stages where youth can successfully present themselves and contribute to their own development. The DSY is a career and leadership training program founded in 1997. Evaluation of the programs focused on 11 criteria drawn from the literature about the merits of supplementary education programs. Results indicate that ASTSN is functioning at a high level of efficiency and effectiveness at community building, involving young people and their families in purposeful activity, encouraging self-confidence, and enhancing competence in self-presentation. DSY is functioning at an excellent level of efficiency and effectiveness in recruiting and engaging a diverse population of young people in a sustained effort at personal development through continuing guided performances in alien environments. -

Performative Psychology, Postmodern Marxism, Social Therapy, Zone of Emotional Development

Performative Psychology, Postmodern Marxism, Social Therapy, Zone of Emotional Development. Draft of four entries in the forthcoming Encyclopedia of Critical Psychology, edited by Thomas Teo and published by Springer Reference. http://www.springerreference.com/docs/navigation.do?m=Encyclopedia+of+Critical+Psy chology+(Behavioral+Science)-book162 PERFORMATIVE PSYCHOLOGY LOIS HOLZMAN Introduction Performative psychology is a shift from a natural science based and individualistic approach to understanding human life to a more cultural and relational approach. It is critical of mainstream psychology in two specific ways: as an alternative understanding and practice of relating to human beings (i.e., a practical-critical methodology based in the human capacity to perform); and as a newly evolving method of inquiry/research (i.e., a performative ways of doing social science). Postmodern Marxists Fred Newman and Lois Holzman are the initial and primary developers of the former, and social constructionists Ken Gergen and Mary Gergen are the initial and primary developers of the latter. Key Words Performatory, performative, performance, Vygotsky, zone of proximal development, relationality, Ken Gergen, Mary Gergen, Holzman, Newman, psychotherapy, education, inquiry, social science research Conceptualization Both orientations of performative psychology are based in an understanding of human life as primarily performatory or performative. While these terms have different origins, senses and reference in different disciplines, today both terms broadly -

Lenora Fulani, Ph.D. CO-FOUNDER, ALL STARS PROJECT, INC

Lenora Fulani, Ph.D. CO-FOUNDER, ALL STARS PROJECT, INC. DIRECTOR, OPERATION CONVERSATION: COPS & KIDS DEAN, UX Trained as a developmental psycholo- gist, Lenora Fulani has been on a four- decade-long journey that has taken her from the elite institutions of academia back to her roots in the poor Black com- munity, where she is known and loved as an outspoken, independent and accom- plished activist and grassroots educator and leader. Her story begins in Chester, Pennsyl- vania, just outside of Philadelphia. “My family was poor, as was almost everyone in Chester,” she says, “and the efects of poverty were devastating to many peo- ple in my family and community. By luck and by circumstance, I was the first in Lenora Fulani holds a press conference on the steps of City my family to be able to go to college. I Hall in NYC (2001). decided pretty much from the start that I wanted to become a psychologist, so that I could come back to Chester and save the members of my family and my friends who were sufering.” As she studied psychology in college (Hofstra University) and graduate school (Columbia University’s Teachers Col- lege and the City University of New York), she became trou- bled by the ways in which the field of psychology related to poverty and its efects, particularly the issues of poor Black people. Even as the new field of Black psychology emerged, she came to see that merely making traditional psychology more attuned to Black people did not automatically mean that it was useful for saving — much less transforming — their lives.