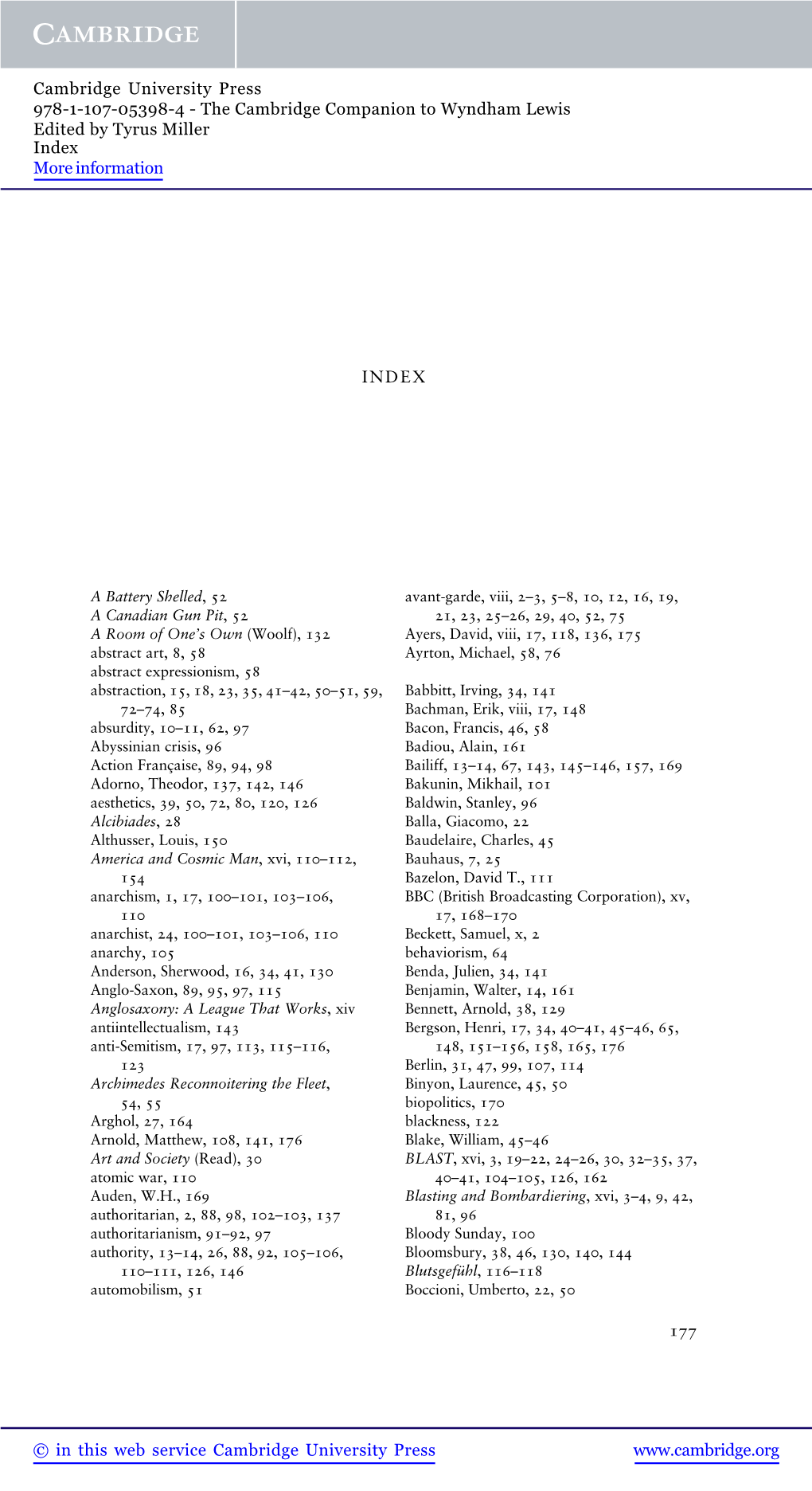

INDEX 177 © in This Web Service Cambridge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Art of a Second Order': the First World War from the British Home Front Perspective

‘ART OF A SECOND ORDER’ The First World War From The British Home Front Perspective by RICHENDA M. ROBERTS A Thesis Submitted to The University of Birmingham For The Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Art History, Film and Visual Studies School of Languages, Art History and Music College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham September 2012 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract Little art-historical scholarship has been dedicated to fine art responding to the British home front during the First World War. Within pre-war British society concepts of sexual difference functioned to promote masculine authority. Nevertheless in Britain during wartime enlarged female employment alongside the presence of injured servicemen suggested feminine authority and masculine weakness, thereby temporarily destabilizing pre-war values. Adopting a socio-historical perspective, this thesis argues that artworks engaging with the home front have been largely excluded from art history because of partiality shown towards masculine authority within the matrices of British society. Furthermore, this situation has been supported by the writing of art history, which has, arguably, followed similar premise. -

The Siberia of the Mind: Egoism in the Writings of Wyndham Lewis ______

The Siberia of the Mind: Egoism in the Writings of Wyndham Lewis ________ David Ashford A room in a great northern city; a typical student squat, pipes half- smoked, bed never-made, books piled on chair and table. Two are in Finnish. The third, ‘stalely open’ ( B1 76), Arghol takes up to shut. It is the Einige und Sein Eigenkeit [sic ]. ‘One of the seven arrows’ in this ‘martyr mind’ ( B1 77) – only this book, by renegade Hegelian Max Stirner, is named by Wyndham Lewis, and rejected. ‘Poof! he flung it out of the window’ ( B1 77). The gesture is timely. According to Paul Edwards, in his account of the artist, ‘Stirner probably had little lasting influence upon Lewis’. 1 Unlike other sources Edwards cites as being central to an understanding of this radical ‘play’ entitled Enemy of the Stars (first published in the Vorticist journal BLAST in 1914), Stirner is not referred to again, does not survive the particularly rough handling he receives in this play. His book is condemned by Arghol as a ‘parasite’, together with all the other books in the room, ‘“Poodles of the mind, Chows and King Charles”’, and is therefore torn up with the rest – left in ‘a pile by the door ready to sweep out’ ( B1 77). But in addition to marking Lewis’s break with Stirner, the incident curiously anticipates the general movement away from the philosophy of Egoism that would take place during the War. Having enjoyed a period of intense interest in the English-speaking world following the publication of Byington’s translation in 1912, The Ego and His Own was to vanish just as suddenly into obscurity again, as writers such as James Joyce, Lewis, and Dora Marsden began to confront problems posed by new materialist theories of the mind (originating in Schopenhauer, developed over the course of the nineteenth century by William James and Henri Bergson, and finding their culmination in the Behaviourist theory of the twentieth century). -

Lewis's Representations of the Body

The Politics and Philosophy of Wyndham Lewis's Representations of the Body Trevor Lovelock Brent Department of English and Comparative Literature, Goldsmiths College, University of London Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, October 2005 ACADEMIC REGISTR *: -ýOOM26 N ER ?T' 0F LO1"P SE GOLDSMITHS -{VJ1! 11111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 -: 8701908642 Abstract The Politics and Philosophy of Wyndham Lewis's Representations of the Body examines the significance of representations of the body in the written work, both theoretical and fictional, of Wyndham Lewis. The central question of the thesis is: how does the body function as a ground for identity in Lewis's work? This question is addressed by looking at five thematic areas of Lewis's work, each of which forms the basis of a chapter: reality, mind-body dualism, gender, race, and the crowd- The work of Slavoj Zizek is used to argue that Lewis's theoretical work is characterised by an antipathy towards `the passion for the Real' and a desire to maintain a belief-sustained sense of `reality'. As a result, the body has an ambivalent status: it is both an emblem of the `reality' of the personality and a threat to it, representing its unavoidable `thingness', its `Real', as it were. This ambivalence is best expressed in Lewis's fiction, where the weaknesses and inconsistencies of his theories are dramatised and exposed. Lewis's ambivalence towards the body results in a split between his theory and his rhetoric, a split that is particularly noticeable in his work on gender and race, in which initially racist and sexist language is undercut by his theoretical discomfort with the biological grounds of such rhetoric. -

ABSTRACT in 1919, Immediately Following the First

ABSTRACT In 1919, immediately following the First World War, the English artist Percy Smith produced a series of seven etchings entitled Dance of Death 1914-1918. Contemporaries responded enthusiastically to his inventive treatment of the subject. This paper reinterprets the series in its historical and social context to better understand its original emotional impact. During the war, censorship created a chasm between the home front and the Western Front. Towards the end of the conflict, soldiers began producing writings and visual art that presented an unfiltered image of the war, which an uneasy public began to crave. These frontline accounts brought the daily perils of the Tommies home, and contained what historian Samuel Hynes called the “aesthetic of direct experience.” This quality of authenticity became a prized ingredient in the public’s eye. Smith illustrated his own military experience through the reimagining of a recognized Medieval trope. The series vicariously transports viewers to the front line, following Death as he meanders through the war zone, pausing here and there to either spare or collect a soldier. By conflating the factual with the macabre, Smith expanded the aesthetic of direct experience to expose not only the war’s physical trauma but its psychological toll. Despite the War’s centennial and reinvigoration of scholarship on its art, Smith’s contributions have remained largely unstudied. My research draws heavily on unpublished archival material housed in the Percy Smith Foundation in Cheshunt, England, and early published sources. Shaw 1 A Modern Dance with Death: Percy Delf Smith and the Aesthetic of Direct Experience Clara Shaw Senior Honors Thesis Submitted to the Art History Department Mount Holyoke College April 2020 Shaw 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A special thank you to the Mount Holyoke College Art History Department for supporting my research with the Linda Kelso Wright Fund. -

ETD Template

THE SEDUCTIVE FALLACY: WOMEN AND FASCISM IN BRITISH DOMESTIC FICTION by Judy Suh B.A., University of Notre Dame, 1994 M.A., University of Pittsburgh, 1996 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2004 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH FACULTY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Judy Suh It was defended on March 31, 2004 and approved by Eric O. Clarke Marcia Landy Barbara Green Paul A. Bové Dissertation Director ii THE SEDUCTIVE FALLACY: WOMEN AND FASCISM IN BRITISH DOMESTIC FICTION Judy Suh, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2004 “The Seductive Fallacy” provides a literary focus for feminist critiques of fascist gender and sexuality. It explores two fascist and three anti-fascist novels—Wyndham Lewis’ The Revenge for Love (1937), Olive Hawks’ What Hope for Green Street? (1945), Virginia Woolf’s The Years (1937), Phyllis Bottome’s The Mortal Storm (1938) and The Lifeline (1946)—that illuminate British domestic fiction’s rhetorical range in the prolonged crisis of liberal hegemony after World War I. Across political purposes and a range of readerships and styles, they illuminate the genre’s efficacy to theorize modern women’s social, political, and cultural agency. In particular, the dissertation’s critical readings of these novels explore fascism’s emergence within liberal democracies. Juxtaposing Lewis and Hawks with literature from the archives of the British Union of Fascists (BUF), the first two chapters stress fascism’s production and consumption of political fantasies prevalent throughout the British novel’s humanist tradition, especially notions of women’s agency inscribed in the traditions of nineteenth- and twentieth-century domestic literature. -

Review Reviewed Work(S): Wyndham Lewis by Jeffrey Meyers and Roy Campbell Review By: Rowland Smith Source: Research in African Literatures, Vol

Review Reviewed Work(s): Wyndham Lewis by Jeffrey Meyers and Roy Campbell Review by: Rowland Smith Source: Research in African Literatures, Vol. 18, No. 1, Special Issue on Literature and Society (Spring, 1987), pp. 118-122 Published by: Indiana University Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4618174 Accessed: 06-05-2020 17:38 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Indiana University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Research in African Literatures This content downloaded from 132.174.251.254 on Wed, 06 May 2020 17:38:51 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 118 Book Reviews "ad hominem grilling" (133) from the formidable Mrs. Q. D. Leavis (considered by many her husband's equal as well as his partner in their journal Scrutiny and indeed in the whole of his critical enterprise), it was F. R. Leavis himself who came to Jacobson's defense. But this was only to restrain his wife's ferocity; his intervention was in the realm of manners rather than of substance. Jacobson is understandably grateful for such personal amiability, but the inci- dent as reported in this essay-especially his unwillingness to realize the force of the Leavisian attack on him-spotlights a certain weakness in his art. -

A Chronology of Wyndham Lewis

A Chronology of Wyndham Lewis 1882 Percy Wyndham Lewis born, Amherst Nova Scotia 1888-93 Isle of Wight 1897-8 Rugby School 1898-1901 Slade School of Art (expelled) 1902 Visits Madrid with Spencer Gore, copying Goya in the Prado 1904-6 Living in Montparnasse, Paris. Meets Ida Vendel (‘Bertha’ in Tarr) 1906 Munich (February – July). 1906-7 Paris 1907 Ends relationship with Ida 1908 – 11 Writes first draught of Tarr, a satirical depiction of Bohemian life in Paris 1908 London 1909 First published writing, ‘The “Pole”’, English Review 1911 Member of Camden Town Group. ‘Cubist’ self-portrait drawings 1912 Decorates ‘Cave of the Golden Calf’ nightclub Exhibits ‘cubist’ paintings and illustrations to Timon of Athens at ‘Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition’ 1913 Joins Fry’s Omega Workshops; walks out of Omega in October with Frederick Etchells, Edward Wadsworth and Cuthbert Hamilton after quarrel with Fry. Portfolio, Timon of Athens published. Begins close artistic association with Ezra Pound 1914 Director, ‘Rebel Art Centre’, Great Ormond Street (March – July) Dissociates self from Futurism and disrupts lecture by Marinetti at Doré Gallery (June) Vorticism launched in Blast (July; edited by Lewis) Introduced to T. S. Eliot by Pound 1915 Venereal infection; Blast no. 2 (June); completes Tarr 1916-18 War service in Artillery, including Third Battle of Ypres and as Official War Artist for Canada and Great Britain 1918-21 With Iris Barry, with whom he has two children 1918 Tarr published. It is praised in reviews by Pound, Eliot and Rebecca West Meets future wife, Gladys Hoskins 1919 Paints A Battery Shelled. -

Wyndham Lewis's

Wyndham Lewis’s ‘Very Bad Thing’: Jazz, Inter-War Culture, and The Apes of God [published in Modernist Cultures , 8.1 (Spring, 2013): 61-81] Nathan Waddell The relationships between jazz and modernist writing have in recent years increasingly come to interest musico-literary scholars. Much of this interest has centred on the links between modernism, jazz, and the cultures of the Harlem Renaissance, whose music and art, in Patti Capel Swartz’s words, extend ‘far beyond its geographic boundaries as well as beyond the relational boundaries of time’. 1 As evidence of this trans-national and trans- temporal influence, especially as it applies to Anglo-American cultural economies, such varied writers as T. S. Eliot, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Virginia Woolf, and Philip Larkin, among many others, have all been considered in relation to jazz and New York in the 1920s and 1930s. 2 Studies of this sort have contributed to the growing centrality of African- American traditions within the field of modernist studies, on the one hand, and provided us with an increasingly nuanced picture of the impact of jazz upon modernism in the literary arts (both as creative stimulus and as despised phenomenon) on the other. However, these alternative interpretations of the jazz ‘influence’ need to be understood as rather more than a simple dichotomy. In Fitzgerald, for instance, we find not only a writer attuned to the prevalence of jazz in twentieth-century modernity, but also a figure whose jazz allusions ‘anxiously suggest that beneath the surface of [what he saw as] the music’s frivolous gaiety lurks the presence of violence and chaos, which threatens to erupt at any moment.’ 3 Nonetheless, Fitzgerald’s complex representations of jazz music – the fact, in other words, that he wrote about jazz culture so extensively in his fiction and 1 Patti Capel Swartz, ‘Masks and Masquerade: The Iconography of the Harlem Renaissance’, Midwest Quarterly , 35.1 (Autumn 1993): pp. -

Rachel Murray Source: Moveabletype, Vol

Article: ‘Unexpected Fruit’: The Ingredients of Tarr Author[s]: Rachel Murray Source: MoveableType, Vol. 8, ‘Dissidence’ (2016) DOI: 10.14324/111.1755-4527.068 MoveableType is a Graduate, Peer-Reviewed Journal based in the Department of English at UCL. © 2016 Rachel Murray. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY) 4.0https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. ‘Unexpected fruit’: The ingredients of Tarr By Rachel Murray ‘condition of continued enjoyment is to resist assimilation’, before concluding: ‘A man is the opposite of his appetite’ (1996, 26)1. Throughout Lewis’s body of work characters often experience revulsion or a lack of appetite before meals, and are often nauseous or sick after eating. Only the most perverse of Lewis’s characters, Otto Kreisler in Tarr (1918) or Julius Ratner in The Apes of God (1930), appear to relish their food, and the sheer aggression of these eating habits is closely associated with other, more monstrous appetites. Lewis’s prose is rough, at times impenetrably dense, and often unappetising in content – full of violence and cruelty, a callous indifference to suffering, and in the 1930s a troubling predilection for fascist ideology. How can we stomach the ideas of an individual who, in 1931, published a forceful defence of Hitler, describing him as a ‘Man of Peace’? I suggest that we can develop a clearer understanding of this much- maligned modernist by engaging with, rather than attempting to either suppress or sublimate, these distasteful qualities. -

![Winner of the 2015 Wyndham Lewis Memorial Trust Essay Prize] ______](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1158/winner-of-the-2015-wyndham-lewis-memorial-trust-essay-prize-4211158.webp)

Winner of the 2015 Wyndham Lewis Memorial Trust Essay Prize] ______

‘Diabolical indigestion’: Forms of Distaste in Wyndham Lewis’s Body of Work [winner of the 2015 Wyndham Lewis Memorial Trust Essay Prize] ________ Rachel Murray Early on in the 1918 edition of Tarr, Lewis’s protagonist, Frederick Tarr, pays a visit to the cramped dwelling of his German fiancée, Bertha Lunken, to break off their engagement. In an attempt to keep relations amicable he brings food with him, and when she becomes upset he introduces the formality of the meal to soak up Bertha’s ‘psychic discharges’ (T1 60). Tarr uses food to reinforce his own self-absorption, but after finding himself unable to prevent Bertha from seeping into his thoughts, he reacts with masticatory aggression: To cover reflection, he set himself to finish lunch. The strawberr- ies were devoured mechanically, with unhungry itch to clear the plate. He had become just a devouring-machine, restless if any of the little red balls still remained in front of it. Bertha’s eyes sought to carry her out of this Present. But they had broken down, depositing her, so to speak, somewhere halfway down the avenue. (T1 70) Ironically, Tarr appropriates eating as a means of thwarting the act of rumination; his transformation into a mere ‘devouring-machine’ is a defence mechanism against the painful indigestion of suppressed feelings. Torn between his desire to assimilate his lover into his life, and his desire to detach himself from her entirely, Tarr’s indecisiveness leaves Bertha feeling only partially digested. Although she has been ‘broken down’ and deposited, Bertha finds herself stuck ‘halfway down the avenue’, lodged in the gullet of this painful process of ‘dis- engagement’ (T1 43). -

IWM North Presents Largest UK Retrospective of Wyndham Lewis

*LAST CHANCE TO SEE – Exhibition closes 1 January 2018* Immediate release IWM North presents largest UK retrospective of Wyndham Lewis From 23 June 2017 until 1 January 2018, IWM North presents Wyndham Lewis: Life, Art, War, the largest UK retrospective of the artist and writer’s work to date. Marking one hundred years since Lewis (18 November 1882 - 7 March 1957) was first commissioned as an official war artist in 1917, the exhibition comprises more than 160 artworks, books, journals and pamphlets from major public and private, national and international collections. Staged in Imperial War Museums’ centenary year, Wyndham Lewis: Life, Art, War is IWM’s largest visual arts exhibition to date. The exhibition also marks 60 years since Wyndham Lewis’s death. A radical force in British art and literature, Lewis was the founder of Britain’s only true avant-garde movement, Vorticism. Lewis’ life and art encompassed the most violent and chaotic period in human history; from the First World War to the nuclear age. He was a controversial figure whose ideas, opinions and personality inspired, enticed and repelled in equal measure. From a mythologized birth in Canada, Lewis spent his youth in England and traveled Europe. In 1913, he joined Roger Fry’s Omega Workshops before setting up his own rival group, aptly named The Rebel Art Centre. From there arose Vorticism in 1914, its arresting manifesto BLAST encapsulating the restless mood pervading Britain on the eve of the First World War. Serving as commissioned artillery officer during the conflict, Lewis was appointed an official war artist first for the Canadians and then the British. -

Night Thoughts on Editing Tarr ______

Night Thoughts on Editing Tarr ________ Scott W. Klein A tale once told cannot be told again; The whistle whistles and it whistles still. (‘Night Thoughts’, C. H. Sisson) It may seem curious to begin an essay about producing a new edition of the 1928 text of Lewis’s Tarr for the Oxford World Classics series with the minor poetic genre of the ‘night thought’. Ever since Edward Young’s eighteenth-century poem of the title, best known to the general reader for its later illustrations by William Blake, the ‘night thought’ has implied a personal look backward, a remembrance of things past carrying with it a melancholy acknowledgement of opportunities lost. Yet as C. H. Sisson suggests in his poem of the same title, the ‘night thought’ implies a paradoxical relation between the one who contemplates and the past. The narratives of the past cannot be recaptured, on one hand, for the tale already told cannot be told again. On the other hand, the work of the past has always maintained a covert existence through time. What was once sounded (‘whistled’) continues to sound, if only in memory. Sisson’s poem implies that the past cannot be recaptured, but also, conversely, that the past has never been lost. I’d like to suggest that this paradox is particularly relevant to the editing of a work such as Tarr . For while Tarr has never been a ‘lost’ work, it is an important novel that has fallen out of print, leading for some a shadowy existence on the cusp of the canon as well as the cusp of availability.