NCCRC Amicus Brief FINAL REVISED

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MLS Game Guide

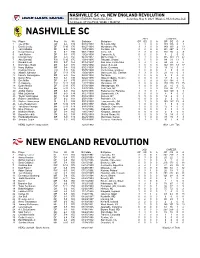

NASHVILLE SC vs. NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION NISSAN STADIUM, Nashville, Tenn. Saturday, May 8, 2021 (Week 4, MLS Game #44) 12:30 p.m. CT (MyTV30; WSBK / MyRITV) NASHVILLE SC 2021 CAREER No. Player Pos Ht Wt Birthdate Birthplace GP GS G A GP GS G A 1 Joe Willis GK 6-5 189 08/10/1988 St. Louis, MO 3 3 0 0 139 136 0 1 2 Daniel Lovitz DF 5-10 170 08/27/1991 Wyndmoor, PA 3 3 0 0 149 113 2 13 3 Jalil Anibaba DF 6-0 185 10/19/1988 Fontana, CA 0 0 0 0 231 207 6 14 4 David Romney DF 6-2 190 06/12/1993 Irvine, CA 3 3 0 0 110 95 4 8 5 Jack Maher DF 6-3 175 10/28/1999 Caseyville, IL 0 0 0 0 3 2 0 0 6 Dax McCarty MF 5-9 150 04/30/1987 Winter Park, FL 3 3 0 0 385 353 21 62 7 Abu Danladi FW 5-10 170 10/18/1995 Takoradi, Ghana 0 0 0 0 84 31 13 7 8 Randall Leal FW 5-7 163 01/14/1997 San Jose, Costa Rica 3 3 1 2 24 22 4 6 9 Dominique Badji MF 6-0 170 10/16/1992 Dakar, Senegal 1 0 0 0 142 113 33 17 10 Hany Mukhtar MF 5-8 159 03/21/1995 Berlin, Germany 3 3 1 0 18 16 5 4 11 Rodrigo Pineiro FW 5-9 146 05/05/1999 Montevideo, Uruguay 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 12 Alistair Johnston DF 5-11 170 10/08/1998 Vancouver, BC, Canada 3 3 0 0 21 18 0 1 13 Irakoze Donasiyano MF 5-9 155 02/03/1998 Tanzania 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 14 Daniel Rios FW 6-1 185 02/22/1995 Miguel Hidalgo, Mexico 0 0 0 0 18 8 4 0 15 Eric Miller DF 6-1 175 01/15/1993 Woodbury, MN 0 0 0 0 121 104 0 3 17 CJ Sapong FW 5-11 185 12/27/1988 Manassas, VA 3 0 0 0 279 210 71 25 18 Dylan Nealis DF 5-11 175 07/30/1998 Massapequa, NY 1 0 0 0 20 10 0 0 19 Alex Muyl MF 5-11 175 09/30/1995 New York, NY 3 2 0 0 134 86 11 20 20 Anibal -

New England Revolution Game Notes June 21, 2009 at 6:30 P.M

SUPERLIGA: NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION VS. SANTOS LAGUNA New England Revolution Game Notes June 21, 2009 at 6:30 p.m. ET New England Santos Laguna 2009 REVOLUTION SCHEDULE 2009 MLS RECORD: 4-4-4 (HOME: 3-1-1 AWAY: 1-3-3) vs. 2009 ALL-COMPETITIONS RECORD: 4-4-4 (HOME: 3-1-1 AWAY: 1-3-3) DATE OPPONENT TIME/RESULT TV Sat., March 21 at San Jose Earthquakes W 1-0 TV38 4-4-4 MLS 5-5-7 Clausura 2009 Sat., March 28 at New York Red Bulls T 1-1 FSC/FSE MATCH INFORMATION Sat., April 4 FC DALLAS W 2-1 TV38 Date: Sunday, June 21, 2009 Fri., April 17 at D.C. United T 1-1 ESPN2/Deportes Kickoff: 6:30 p.m. ET Sat., April 25 at Real Salt Lake L 0-6 TV38 Location: Gillette Stadium (Foxborough, Mass.) Sun., May 3 HOUSTON DYNAMO L 0-2 TV38/Telefutura National TV: Telefutura (Spanish), superliga2009.com (English) Sat., May 9 at Chicago Fire T 1-1 TV38 National Radio: ESPN Deportes Radio (Spanish) Sat., May 16 COLORADO RAPIDS T 1-1 TV38 Revolution Radio: WEEI Radio Network (Brad Feldman - play-by-play, Seamus Malin - analyst) Sat., May 23 at Toronto FC L 1-3 TV38 Revolution PR Contacts: Sat., May 30 D.C. UNITED W 2-1 TV38 Lizz Summers (o: 508-549-0496) (c: 617-571-2219), [email protected] Sun., June 7 NEW YORK RED BULLS W 4-0 TV38 Jeff Lemieux (o: 508-549-0185) (c: 508-958-1370), [email protected] Santos Laguna PR Contact: Sat., June 13 at Kansas City Wizards L 1-3 TV38 Roberto Fernández Espinosa (c: 871-211-1460) SUM PR Contact: Sun., June 21 SUPERLIGA: SANTOS (MEX) 6:30 p.m. -

NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION Vs FC CINCINNATI: SATURDAY, AUGUST 21, 2021

NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION vs FC CINCINNATI: SATURDAY, AUGUST 21, 2021 GAME CAPSULE THE PRESS BOX Broadcast Information Regular SEASON Television: WBZ-TV, myRITV Match #22 Pregame Show: Revolution Kickoff at 7:30 p.m. on WBZ vs fC cincinnati Talent: Brad Feldman (Play-by-Play), Charlie Davies (Analyst), Naoko Funayama (sideline) Saturday, August 21 Radio: 98.5 The Sports Hub (English); WBIX 1260 Nossa Radio (Portuguese) 2021 MLS Record: Gillette Stadium 2021 MLS Record: Streaming: ESPN+ for out-of-market subscribers 14-3-4, 46 pts. (Foxborough, Mass.) 3-7-8, 17 pts. Postgame Press Conference: Click here to participate in the postgame 1st in East. Conf. 8:00 p.m. ET 13th in East. Conf. press conference with Bruce Arena and select Revolution players. LAST STARTING XI (AUGUST 18 vS. D.C. UNITED) 2021 MLS SCHEDULE 7 BOU 10 BUNBURY 2021 MLS RECORD: 14-3-4 19 GP, 17 GS, 12 G, 3 A 18 GP, 5 GS, 3 G, 0 A (Home: 8-1-1 Away: 6-2-3) 25 TRAUSTASON 26 McNAMARA 2021 REGULAR SEASON SCHEDULE 20 GP, 15 GS, 2 G, 5 A 21 GP, 10 GS, 2 G, 3 A Date Opponent Time / Result Broadcast Sat., April 17 at Chicago Fire FC T, 2-2 WBZ/myRITV Sat., April 24 D.C. UNITED W, 1-0 TV38/myRITV Sat., May 1 ATLANTA UNITED FC W, 2-1 TV38/myRITV 5 KAPTOUM 13 MACIEL 13 GP, 6 GS, 0 G, 1 A 15 GP, 13 GS, 0 G, 0 A Sat., May 8 at Nashville SC L, 0-2 TV38/myRITV Wed., May 12 at Philadelphia Union T, 1-1 TV38/myRITV 24 JONES 28 DeLaGARZA Sun., May 16 COLUMBUS CREW W, 1-0 ESPN2 18 GP, 18 GS, 2 G, 4 A 6 GP, 3 GS, 0 G, 1 A Sat., May 22 NEW YORK RED BULLS W, 3-1 TV38/myRITV Sat., May 29 at FC Cincinnati W, 1-0 TV38/myRITV/CoziTV 4 KESSLER 2 FARRELL Sat., June 19 at New York City FC W, 3-2 TV38/myRITV/CoziTV 16 GP, 13 GS, 0 G, 0 A 21 GP, 21 GS, 0 G, 1 A Wed., June 23 NEW YORK RED BULLS W, 3-2 TV38/myRITV Sun., June 27 at FC Dallas L, 2-1 TV38/myRITV 30 TURNER Sat., July 3 at Columbus Crew T, 2-2 ESPN 16 GP, 16 GS, 1.19 GAA Wed., July 7 TORONTO FC L, 2-3 TV38/myRITV/CoziTV Sat., July 17 at Atlanta United FC W, 1-0 ESPN PRONUNCIATION GUIDE Wed., July 21 at Inter Miami CF W, 5-0 TV38/myRITV # Player Pos. -

New England Revolution Game Notes May 13, 2006 at 7 P.M

REVOLUTION VS. CD CHIVAS USA -- SATURDAY, MAY 13, 2006 -- 7 P.M. ET PAGE 1 NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION GAME NOTES MAY 13, 2006 AT 7 P.M. ET 2006 REVOLUTION SCHEDULE OVERALL RECORD: 2-2-1 HOME: 1-1-0 AWAY: 1-1-1 DATE OPPONENT TIME/RESULT TV Sat., April 1 at Los Angeles Galaxy W 1-0 ESPN2 Sat., April 8 at New York Red Bulls T 0-0 WB56 Sat., April 15 at Kansas City Wizards L 0-1 WB56 EW NGLAND VS HIVAS N E . CD C USA Sun., April 30 CHICAGO FIRE L 1-2 WB56 (2-2-1, 7 PTS.) (1-2-1, 4 PTS.) Sat., May 6 LOS ANGELES GALAXY W 4-0 ESPN2 Sat., May 13 CD CHIVAS USA 7:00 PM FSN Sat., May 20 at FC Dallas 8:30 PM WB56 ATCH NFORMATION Sat., May 27 HOUSTON DYNAMO 7:30 PM FSN M I Sat., June 3 at D.C. United 7:30 PM WB56 Date: Saturday, May 13, 2006 Time: 7 p.m. ET Sun., June 11 at Chicago Fire 7:00 PM FSN Location: Gillette Stadium, Foxborough, Mass. Sat., June 17 D.C. UNITED 6:00 PM FSN Wed., June 21 at Columbus Crew 7:30 PM FSN TV: FSN (Brad Feldman – play-by-play, Greg Lalas – analyst) Sat., June 24 at Real Salt Lake 9:00 PM FSN Satellite Information: KU BAND SBS 6 Tr. 11A Upper, Uplink: Wed., June 28 FC DALLAS 7:30 PM FSN 14271(V), Downlink: 11971(H), Symbol Rate: 6.1113 Sat., July 1 NEW YORK RED BULLS 6:00 PM ESPN2 Radio: WRKO 680 AM Tues., July 4 at Colorado Rapids 9:30 PM FSN Spanish Radio: WJDA 1300 AM (Pedro Rosalez – play-by-play, Sat., July 8 at Chicago Fire 8:30 PM WB56 Marino Velasquez – analyst, Baltazar Palencia – sideline) Fri., July 14 REAL SALT LAKE 7:30 PM FSN Referee: Mark Geiger Wed., July 19 at Kansas City Wizards 8:30 PM FSN Referee's Assistants: Paul Scott, CJ Morgante Sat., July 22 at Houston Dynamo 8:30 PM WB56 Fourth Official: Erich Simmons Wed., July 26 D.C. -

MLS Game Guide

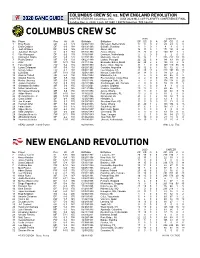

COLUMBUS CREW SC vs. NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION MAPFRE STADIUM, Columbus, Ohio AUDI 2020 MLS CUP PLAYOFFS CONFERENCE FINAL Sunday, Dec. 6, 2020, 3 p.m. ET (ABC / ESPN Deportes, TVA Sports) COLUMBUS CREW SC 2020 CAREER No. Player Pos Ht Wt Birthdate Birthplace GP GS G A GP GS G A 1 Eloy Room GK 6-3 179 02/06/1989 Nijmegen, Netherlands 17 17 0 0 29 29 0 0 2 Chris Cadden DF 6-0 168 09/19/1996 Bellshill, Scotland 8 3 0 1 8 3 0 1 3 Josh Williams DF 6-2 185 04/18/1988 Akron, OH 12 11 0 1 174 154 9 6 4 Jonathan Mensah DF 6-2 183 07/13/1990 Accra, Ghana 23 23 0 0 100 97 3 1 5 Vito Wormgoor DF 6-2 179 11/16/1988 Leersum, Netherlands 2 2 0 0 2 2 0 0 6 Darlington Nagbe MF 5-9 170 07/19/1990 Monrovia, Liberia 15 14 1 1 285 272 30 38 7 Pedro Santos MF 5-6 139 04/22/1988 Lisbon, Portugal 22 22 6 8 94 89 18 23 8 Artur MF 5-11 154 03/11/1996 Brumado, Bahia, Brazil 22 20 2 4 108 99 2 9 9 Fanendo Adi FW 6-4 185 10/10/1990 Benue State, Nigeria 11 1 0 0 149 110 55 14 10 Lucas Zelarayan MF 5-9 154 06/20/1992 Cordoba, Argentina 16 12 6 4 16 12 6 4 11 Gyasi Zardes FW 6-1 187 09/02/1991 Los Angeles, CA 21 20 12 4 213 197 78 23 12 Luis Diaz MF 5-11 159 12/06/1998 Nicoya, Costa Rica 21 14 0 3 34 23 2 7 13 Andrew Tarbell GK 6-3 194 10/07/1993 Mandeville, LA 7 6 0 0 48 46 0 0 14 Waylon Francis DF 5-9 160 09/20/1990 Puerto Limon, Costa Rica 4 2 0 0 115 98 0 19 16 Hector Jimenez MF 5-9 145 11/03/1988 Huntington Park, CA 8 4 0 1 176 118 6 25 17 Jordan Hamilton FW 6-0 185 03/17/1996 Scarborough, ON, Canada 2 0 0 0 59 28 11 3 18 Sebastian Berhalter MF 5-9 155 05/10/2001 London, England 9 4 0 0 9 4 0 0 19 Milton Valenzuela DF 5-6 145 08/13/1998 Rosario, Argentina 19 17 0 3 49 46 1 9 20 Emmanuel Boateng MF 5-6 150 01/17/1994 Accra, Ghana 10 3 0 1 121 68 9 14 21 Aidan Morris MF 5-10 158 11/16/2001 Fort Lauderdale, FL 10 2 0 0 10 2 0 0 22 Derrick Etienne Jr. -

WESTFIELD LEADER Pq in I/5 R> CM UJ the Leading and Most Widely Circulated Weekly Newspaper in Union County

o o >- i- - < -3 o: « z: R < HUlL THE WESTFIELD LEADER pq in i/5 r> CM UJ The Leading and Most Widely Circulated Weekly Newspaper In Union County USI'S 6K0020 NINETY-FOURTH YEAR, NO. 44 Second ClaM PoiUKC I'&id WESTFIELD, NEW JERSEY, THURSDAY, MAY 31, 1984 Publlihtd at Wullifld. N. J. Evtry Thund.y 18 Pages—25 Cents Windows on the Westfield World Less than Half of Town's Depict 12 Disciples of Christ Electorate Expected to Vote By Maryanne Melloaii While Westfield has mainder independent. U.S. Senate nomination to town committees, the St. Paul's Church on East Broad St. is almost 18,000 residents While there are no local lure Republicans to vote. ballots for both parties are the location of another first for registered to vote, fewer contests in either With voters electing long. Westfield. Indeed, the church's new than half are expected to Republican and Democrat delegates to this summer's One machine will be engraved glass windows, created by ar- go to the polls on Primary Primaries, the Presiden- Republican and available at each of the tist Warwick Hutton, are not only a first Day'between the hours of 7 tial Primary is expected to Democratic National Con- following district polling for Westfield, but for the United States. a.m. and 8 p.m. Tuesday. attract Democrats to the ventions, as well as places: Mr. Hutton and his wife will be on hand Close to half of Westfield polls, and a contest for the members of local political 1st Ward 1st District for a dedication ceremony June 10 at the voters are not affiliated Roosevelt Junior High 10:45 morning service. -

Table of Contents

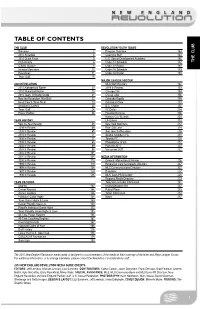

TABLE OF CONTENTS THE CLUB REVOLUTION YOUTH TEAMS Welcome 2 Program Overview 184 2010 Schedule 4 Coaching Staff 184 2010 Quick Facts 5 U.S. Soccer Development Academy 186 Club History 6 Under-18 Schedule 187 THE CLUB Gillette Stadium 8 Under-18 Roster 188 Investor/Operators 10 Under-16 Schedule 189 Executives 11 Under-16 Roster 190 Team Staff 15 MAJOR LEAGUE SOCCER 2009 REVOLUTION MLS Staff Directory 192 2010 Alphabetical Roster 20 2009 In Review 193 2010 Numerical Roster 20 Chicago Fire 194 2010 Team TV/Radio Guide 21 Chivas USA 196 How the Revolution Was Built 22 Colorado Rapids 198 Head Coach Steve Nicol 23 Columbus Crew 200 Assistant Coaches 24 D.C. United 202 Team Staff 24 FC Dallas 204 Player Profiles 26 Houston Dynamo 206 Kansas City Wizards 208 TEAM HISTORY LA Galaxy 210 Year-by-Year Results 58 New York Red Bulls 212 2009 In Review 59 Real Salt Lake 214 2008 In Review 65 San Jose Earthquakes 216 2007 In Review 71 Seattle Sounders FC 218 2006 In Review 77 Toronto FC 220 2005 In Review 83 Philadelphia Union 222 2004 In Review 89 Portland 2011 222 2003 In Review 95 Vancouver 2011 222 2002 In Review 101 2001 In Review 108 MEDIA INFORMATION 2000 In Review 113 General Information & Policies 226 1999 In Review 119 Revolution Communications Directory 227 1998 In Review 124 MLS Communications Directory 227 1997 In Review 129 Directions 227 1996 In Review 135 MLS Team PR Directory 228 Regional Media Directory 229 TEAM RECORDS Television & Radio Information 231 Awards 142 revolutionsoccer.net 232 Career Records 144 Patriot Place 233 Annual Leaders 146 Ticket Information 234 Individual Game Highs 148 Notes 237 Team Game Highs & Lows 149 Career Playoffs Statistics 150 Playoffs Individual Game Highs 152 Team Playoffs Game Highs & Lows 153 All-Time Player Registry 154 All-Time Coaching Registry 167 Coaching Records 167 Important Dates of Note 168 Draft History 176 Lamar Hunt U.S. -

1-18 the Club.Qxp

TABLE OF CONTENTS THE CLUB MAJOR LEAGUE SOCCER 2008 Schedule 4 MLS Staff Directory 180 2008 Team Overview 5 MLS Fact Sheet 181 Club History 6 2008 Composite Schedule 183 Gillette Stadium 8 2008 Rules & Regulations 185 THE CLUB Revolution and Kraft Sports Group 9 2008 Rules of Competition & Playoff Format 188 Investor/Operators: The Kraft Family 10 MLS Career Statistics 190 Team Executives 12 SuperLiga 192 Team Staff 16 2007 In Review 193 2007 Reserve Division 197 2008 REVOLUTION 2008 Alphabetical Roster 20 MLS TEAMS 2008 Numerical Roster 20 Chicago Fire 200 2008 Team TV/Radio Guide 21 Chivas USA 202 How the Revolution Was Built 22 Colorado Rapids 204 Head Coach Steve Nicol 23 Columbus Crew 206 Assistant Coaches 24 D.C. United 208 Team Staff 25 FC Dallas 210 Player Profiles 26 Houston Dynamo 212 Kansas City Wizards 214 TEAM HISTORY Los Angeles Galaxy 216 Year-by-Year Results 66 New York Red Bulls 218 2007 In Review 67 Real Salt Lake 220 2006 In Review 74 San Jose 222 2005 In Review 80 Toronto FC 224 2004 In Review 86 MLS Seattle 2009 226 2003 In Review 92 2008 Conference Alignments 226 2002 In Review 98 2001 In Review 105 MEDIA INFORMATION 2000 In Review 110 General Information & Policies 230 1999 In Review 116 Revolution Communications Contacts 231 1998 In Review 121 MLS Communications Contacts 231 1997 In Review 126 Directions 231 1996 In Review 132 MLS Team PR Directory 232 Regional Media Directory 233 TEAM RECORDS Television & Radio Information 235 Award & Honors 142 revolutionsoccer.net 236 Career Records 144 Patriot Place 237 Annual Leaders 146 Ticket Information 238 Individual Game Highs 148 Notes 239 Team Game Highs & Lows 149 Career Playoffs Statistics 150 Playoffs Individual Game Highs 151 Team Playoffs Game Highs & Lows 152 All-Time Player Registry 153 All-Time Coaching Registry 164 Coaching Records 164 Important Dates of Note 165 Draft History 173 Lamar Hunt U.S. -

225-238 Media 2010.Pdf

2010 MEDIA POLICIES The New England Revolution is pleased to assist you in your coverage of the MEDIA PARKING team. As an organization, Kraft Sports Group - the New England Patriots and New For the majority of the season, all media are to park in Lot 6 for both training and England Revolution - has specific media policies of which you should be aware as you games unless otherwise directed. To enter the stadium, please use the North Entrance prepare to cover the team. (P1) off Rt. 1 and stop at the security gatehouse at the entrance to Gillette Stadium. You will be directed to Lot 6, or the in-use lot, from there. PROFESSIONAL CONDUCT All media who have been issued credentials - season, day-of-game or training - PLAYER AND STAFF INTERVIEWS are expected to follow the guidelines set forth in this document, as well as the instruc- All interviews for Revolution players, coaches, executives and staff must be tions of the Revolution staff, stadium employees and security, or risk limitation of coordinated through the Communications office. access or revocation of credentials. Training: Unless weather conditions preclude it, all player and staff interviews will Media access issued with the purpose of providing access to interviews and writ- be conducted on the practice fields at the conclusion of the training session. All inter- ten, audio and visual accounts of the team, as appropriate. No member of the media view requests will be collected by members of the Communications staff during the should use this access for autographs, personal photographs or commercial requests. -

Blf Nsipa Newsline

Volume 35 • Issue 2 Winter 2011 www.nsipa.org 100 Year History President’s Message 100 Year History By Ed Galloway, APA, CIPA ooff WWoorrkkeerrss’’ Happy New Year! The Board of Directors at NSIPA has been very busy since we last reported to you. CCoommppeennssaattiioonn Shortly after I wrote the last message, I was contacted by AMP, our management company, and asked if they could assist us in returning to BLF Management. After much negotiation, the return happened and Brad Feldman is again our executive director as of December 1, 2010. Brad has immediately jumped back into the management of NSIPA and has many new ideas and projects that he’s already started or shared with the board. One of the immediate updates was a relaunch of our website. Make sure you visit www.nsipa.org and check out the new features; we are excited about the new format. He is also personally contacting non-renewals and old friends of NSIPA, so please welcome him back if he speaks to you! We are now focusing our time to the operation of the society. We are busy finalizing the plans for our Indianapolis Annual Seminar on April 17-19. Complete details of the meeting and registration materials are within this issue. National newsmakers often frighten us with reports of unemployment, bankruptcies, homeless families, and such. As auditors, we are Also Inside: all aware of the economy of our areas; we often see it up close and hear the sad stories of people On the Road: Eating Healthy and as they suffer. -

New England Revolution @ Inter Miami Cf: Wednesday, July 21, 2021

NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION @ INTER MIAMI CF: WEDNESDAY, JULY 21, 2021 GAME CAPSULE THE PRESS BOX Broadcast Information 2021 MLS Television: WSBK-TV38, myRITV Regular Season Talent: Brad Feldman (Play-by-Play), Charlie Davies (Analyst) Match #15 Radio: 98.5 The Sports Hub (English); WBIX 1260 Nossa Radio (Portuguese) Streaming: ESPN+ for out-of-market subscribers Wednesday, July 21 2021 MLS Record: DRV PNK Stadium 2021 MLS Record: Postgame Press Conference: Click here to participate in the postgame 8-3-3, 27 pts. (Fort Lauderdale, Florida) 2-7-2, 8 pts. press conference with Bruce Arena and select Revolution players. 1st in East. Conf. 7:30 p.m. ET 14th in East. Conf. LAST STARTING XI (JULy 17 at ATLANTA) 2021 MLS SCHEDULE 7 BOU 9 BUKSA 2021 MLS RECORD: 8-3-3 12 GP, 11 GS, 7 G, 2 A 14 GP, 8 GS, 5 G, 1 A (Home: 5-1-0 Away: 3-2-3) 22 GIL 2021 REGULAR SEASON SCHEDULE 14 GP, 14 GS, 2 G, 10 A Date Opponent Time / Result Broadcast Sat., April 17 at Chicago Fire FC T, 2-2 WBZ/myRITV Sat., April 24 D.C. UNITED W, 1-0 TV38/myRITV 13 MACIEL 5 KAPTOUM 8 POLSTER Sat., May 1 ATLANTA UNITED FC W, 2-1 TV38/myRITV 10 GP, 9 GS, 0 G, 0 A 7 GP, 3 GS, 0 G, 1 A 14 GP, 13 GS, 0 G, 0 A Sat., May 8 at Nashville SC L, 0-2 TV38/myRITV Wed., May 12 at Philadelphia Union T, 1-1 TV38/myRITV 24 JONES 15 BYE Sun., May 16 COLUMBUS CREW W, 1-0 ESPN2 13 GP, 13 GS, 1 G, 2 A 14 GP, 13 GS, 1 G, 1 A Sat., May 22 NEW YORK RED BULLS W, 3-1 TV38/myRITV Sat., May 29 at FC Cincinnati W, 1-0 TV38/myRITV 4 KESSLER 2 FARRELL Sat., June 19 at New York City FC W, 3-2 TV38/myRITV 12 GP, 9 GS, 0 G, 0 A 14 GP, 14 GS, 0 G, 1 A Wed., June 23 NEW YORK RED BULLS W, 3-2 TV38/myRITV Sun., June 27 at FC Dallas L, 2-1 TV38/myRITV 18 KNIGHTON Sat., July 3 at Columbus Crew T, 2-2 ESPN 2 GP, 2 GS, 1.50 GAA Wed., July 7 TORONTO FC L, 2-3 TV38/myRITV/CoziTV Sat., July 17 at Atlanta United FC W, 1-0 ESPN PRONUNCIATION GUIDE Wed., July 21 at Inter Miami CF 7:30 p.m. -

New England Revolution @ Atlanta United Fc: Saturday, July 17, 2021

NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION @ ATLANTA UNITED FC: SATURDAY, JULY 17, 2021 GAME CAPSULE THE PRESS BOX Broadcast Information 2021 MLS Television: ESPN (English), ESPN Deportes (Spanish) Regular Season Talent: Adrian Healey (Play-by-Play), Alejandro Moreno (Analyst) Match #14 Radio: 98.5 The Sports Hub (English); WBIX 1260 Nossa Radio (Portuguese) Talent: Brad Feldman (Play-by-Play), Charlie Davies (Analyst) Saturday, July 17 Streaming: ESPN+ for out-of-market subscribers 2021 MLS Record: Mercedes-Benz Stadium 2021 MLS Record: 7-3-3, 24 pts. (Atlanta, Georgia) 2-3-7, 13 pts. Postgame Press Conference: Click here to participate in the postgame 1st in East. Conf. 5:00 p.m. ET 10th in East. Conf. press conference with Bruce Arena and select Revolution players. LAST STARTING XI (JULy 7 VS. TORONTO) 2021 MLS SCHEDULE 7 BOU 9 BUKSA 2021 MLS RECORD: 7-3-3 11 GP, 10 GS, 6 G, 2 A 13 GP, 7 GS, 5 G, 0 A (Home: 5-1-0 Away: 2-2-3) 10 BUNBURY 22 GIL 2021 REGULAR SEASON SCHEDULE 10 GP, 2 GS, 1 G, 0 A 13 GP, 13 GS, 2 G, 10 A Date Opponent Time / Result Broadcast Sat., April 17 at Chicago Fire FC T, 2-2 WBZ/myRITV Sat., April 24 D.C. UNITED W, 1-0 TV38/myRITV 13 MACIEL 8 POLSTER Sat., May 1 ATLANTA UNITED FC W, 2-1 TV38/myRITV 9 GP, 8 GS, 0 G, 0 A 13 GP, 12 GS, 0 G, 0 A Sat., May 8 at Nashville SC L, 0-2 TV38/myRITV Wed., May 12 at Philadelphia Union T, 1-1 TV38/myRITV 24 JONES 15 BYE Sun., May 16 COLUMBUS CREW W, 1-0 ESPN2 12 GP, 12 GS, 1 G, 2 A 13 GP, 12 GS, 1 G, 1 A Sat., May 22 NEW YORK RED BULLS W, 3-1 TV38/myRITV Sat., May 29 at FC Cincinnati W, 1-0 TV38/myRITV 4 KESSLER 2 FARRELL Sat., June 19 at New York City FC W, 3-2 TV38/myRITV 11 GP, 8 GS, 0 G, 0 A 13 GP, 13 GS, 0 G, 1 A Wed., June 23 NEW YORK RED BULLS W, 3-2 TV38/myRITV Sun., June 27 at FC Dallas L, 2-1 TV38/myRITV 18 KNIGHTON Sat., July 3 at Columbus Crew T, 2-2 ESPN 1 GP, 1 GS, 3.00 GAA Wed., July 7 TORONTO FC L, 2-3 TV38/myRITV/CoziTV Sat., July 17 at Atlanta United FC 5:00 p.m.