Is This Bizarro World?” the Adaptation of Characterisation and Intertextuality in German

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

215-345-7966 BLUM-MOORE REPORTING SERVICES, INC. 1 BEFORE NEW HOPE BOROUGH COUNCIL in Re: Special Meeti

1 BEFORE NEW HOPE BOROUGH COUNCIL In Re: Special Meeting - - - - MONDAY, NOVEMBER 5, 2018 - - - - A public meeting was held at the Borough Municipal Building, 125 New Street, New Hope, Pennsylvania 18938, commencing at 7:00 p.m. on the day and date above set forth, before Tara Wilson, Professional Reporter and Notary Public in and for the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. - - - - BLUM-MOORE REPORTING SERVICES, INC. 350 SOUTH MAIN STREET, SUITE 203 DOYLESTOWN, PENNSYLVANIA 18901 (215) 345-7966 BLUM-MOORE REPORTING SERVICES, INC. www.blummoore.com 215-345-7966 2 4 1 BOROUGH COUNCIL: 1 MS. KINGSLEY: I'd like to call the 2 Mayor Laurence D. Keller 2 meeting to order. All rise for the pledge of Alison Kingsley, President 3 Connie Gering, Vice-President 3 allegiance. Tina Leifer Rettig (Late arrival) 4 (Pledge of allegiance was recited.) 4 Peter Meyer Ken Maisel 5 MS. KINGSLEY: One special 5 Dan Dougherty 6 announcement, they'll be an executive session 6 E.J. Lee, Borough Manager 7 after this meeting. T.J. Walsh, Esquire, Solicitor 7 8 Tonight's meeting is for the purpose of ALSO PRESENT: 9 hearing the zoning application for the Mansion 8 10 Inn. Chief Michael Cummings 9 New Hope Police Department 11 UNIDENTIFIED SPEAKER: Can't hear you. 10 Jim Ennis, Borough Zoning Officer 12 MS. KINGSLEY: The purpose of tonight's 11 Curtin & Heefner, LLP 13 By Paul Cohen, Esquire meeting is to the hearing the zoning application 12 1040 Stony Hill Road 14 for the Mansion Inn. And our solicitor T.J. Suite 150 15 Walsh, will frame the purpose and the function of 13 Yardley, PA 19067 For the Applicant - Mansion Inn 16 the meeting this evening. -

Radio 4 Listings for 2 – 8 May 2020 Page 1 of 14

Radio 4 Listings for 2 – 8 May 2020 Page 1 of 14 SATURDAY 02 MAY 2020 Professor Martin Ashley, Consultant in Restorative Dentistry at panel of culinary experts from their kitchens at home - Tim the University Dental Hospital of Manchester, is on hand to Anderson, Andi Oliver, Jeremy Pang and Dr Zoe Laughlin SAT 00:00 Midnight News (m000hq2x) separate the science fact from the science fiction. answer questions sent in via email and social media. The latest news and weather forecast from BBC Radio 4. Presenter: Greg Foot This week, the panellists discuss the perfect fry-up, including Producer: Beth Eastwood whether or not the tomato has a place on the plate, and SAT 00:30 Intrigue (m0009t2b) recommend uses for tinned tuna (that aren't a pasta bake). Tunnel 29 SAT 06:00 News and Papers (m000htmx) Producer: Hannah Newton 10: The Shoes The latest news headlines. Including the weather and a look at Assistant Producer: Rosie Merotra the papers. “I started dancing with Eveline.” A final twist in the final A Somethin' Else production for BBC Radio 4 chapter. SAT 06:07 Open Country (m000hpdg) Thirty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Helena Merriman Closed Country: A Spring Audio-Diary with Brett Westwood SAT 11:00 The Week in Westminster (m000j0kg) tells the extraordinary true story of a man who dug a tunnel into Radio 4's assessment of developments at Westminster the East, right under the feet of border guards, to help friends, It seems hard to believe, when so many of us are coping with family and strangers escape. -

Media Culture for a Modern Nation? Theatre, Cinema and Radio in Early Twentieth-Century Scotland

Media Culture for a Modern Nation? Theatre, Cinema and Radio in Early Twentieth-Century Scotland a study © Adrienne Clare Scullion Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD to the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Faculty of Arts, University of Glasgow. March 1992 ProQuest Number: 13818929 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818929 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Frontispiece The Clachan, Scottish Exhibition of National History, Art and Industry, 1911. (T R Annan and Sons Ltd., Glasgow) GLASGOW UNIVERSITY library Abstract This study investigates the cultural scene in Scotland in the period from the 1880s to 1939. The project focuses on the effects in Scotland of the development of the new media of film and wireless. It addresses question as to what changes, over the first decades of the twentieth century, these two revolutionary forms of public technology effect on the established entertainment system in Scotland and on the Scottish experience of culture. The study presents a broad view of the cultural scene in Scotland over the period: discusses contemporary politics; considers established and new theatrical activity; examines the development of a film culture; and investigates the expansion of broadcast wireless and its influence on indigenous theatre. -

Normalizing Monstrous Bodies Through Zombie Media

Your Friendly Neighbourhood Zombie: Normalizing Monstrous Bodies Through Zombie Media by Jessica Wind A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Communication Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2016 Jess Wind Abstract Our deepest social fears and anxieties are often communicated through the zombie, but these readings aren’t reflected in contemporary zombie media. Increasingly, we are producing a less scary, less threatening zombie — one that is simply struggling to navigate a society in which it doesn’t fit. I begin to rectify the gap between zombie scholarship and contemporary zombie media by mapping the zombie’s shift from “outbreak narratives” to normalized monsters. If the zombie no longer articulates social fears and anxieties, what purpose does it serve? Through the close examination of these “normalized” zombie media, I read the zombie as possessing a non- normative body whose lived experiences reveal and reflect tensions of identity construction — a process that is muddy, in motion, and never easy. We may be done with the uncontrollable horde, but we’re far from done with the zombie and its connection to us and society. !ii Acknowledgements I would like to start by thanking Sheryl Hamilton for going on this wild zombie-filled journey with me. You guided me as I worked through questions and gained confidence in my project. Without your endless support, thorough feedback, and shared passion for zombies it wouldn’t have been nearly as successful. Thank you for your honesty, deadlines, and coffee. I would also like to thank Irena Knezevic for being so willing and excited to read this many pages about zombies. -

Spy Culture and the Making of the Modern Intelligence Agency: from Richard Hannay to James Bond to Drone Warfare By

Spy Culture and the Making of the Modern Intelligence Agency: From Richard Hannay to James Bond to Drone Warfare by Matthew A. Bellamy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in the University of Michigan 2018 Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Susan Najita, Chair Professor Daniel Hack Professor Mika Lavaque-Manty Associate Professor Andrea Zemgulys Matthew A. Bellamy [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-6914-8116 © Matthew A. Bellamy 2018 DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to all my students, from those in Jacksonville, Florida to those in Port-au-Prince, Haiti and Ann Arbor, Michigan. It is also dedicated to the friends and mentors who have been with me over the seven years of my graduate career. Especially to Charity and Charisse. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Dedication ii List of Figures v Abstract vi Chapter 1 Introduction: Espionage as the Loss of Agency 1 Methodology; or, Why Study Spy Fiction? 3 A Brief Overview of the Entwined Histories of Espionage as a Practice and Espionage as a Cultural Product 20 Chapter Outline: Chapters 2 and 3 31 Chapter Outline: Chapters 4, 5 and 6 40 Chapter 2 The Spy Agency as a Discursive Formation, Part 1: Conspiracy, Bureaucracy and the Espionage Mindset 52 The SPECTRE of the Many-Headed HYDRA: Conspiracy and the Public’s Experience of Spy Agencies 64 Writing in the Machine: Bureaucracy and Espionage 86 Chapter 3: The Spy Agency as a Discursive Formation, Part 2: Cruelty and Technophilia -

Dr. Horribles Sing-Along Blog: the Book 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

DR. HORRIBLES SING-ALONG BLOG: THE BOOK 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Joss Whedon | 9781848568624 | | | | | Dr. Horribles Sing-Along Blog: The Book 1st edition PDF Book Last week, I broke down the opening act of Dr. Full script including the Commentary: The Musical version , all the sheet music, and some behind- the-scenes and backstory. Horrible played by Neil Patrick Harris , an aspiring supervillain ; Captain Hammer Nathan Fillion , his superheroic nemesis; and Penny Felicia Day , a charity worker and their shared love interest. Retrieved December 7, Reply to Bubbles. Archived from the original on July 20, Kendra Preston Leonard has collected a varying selection of essays that explore music and sound in Joss Whedon's works. Horrible's Sing-Along Blog and stated that due to its success they had been able to pay the crew and the bills. Horrible's Sing-Along Blog Soundtrack made the top 40 Album list on release, despite being a digital exclusive only available on iTunes. Horrible's Live Sing-Along Blog" hits the stage". Then Dr. Lassie, and she always gets a treat So you wonder what your part is Because you're homeless and depressed But home is where the heart is So your real home's in your chest Everyone's a hero in their own way Everyone's got villains they must face They're not as cool as mine But folks you know it's fine to know your place Everyone's a hero in their own way In their own not-that-heroic way So I thank my girlfriend Penny Yeah, we totally had sex She showed me there's so many different muscles I can flex There's the deltoids of compassion, There's the abs of being kind It's not enough to bash in heads You've got to bash in minds Everyone's a hero in their own way Everyone's got something they can do Get up go out and fly Especially that guy, he smells like poo Everyone's a hero in their own way You and you and mostly me and you I'm poverty's new sheriff And I'm bashing in the slums A hero doesn't care if you're a bunch of scary alcoholic bums Everybody! Itsjustsomerandomguy, the Guild, Dr. -

Buffy at Play: Tricksters, Deconstruction, and Chaos

BUFFY AT PLAY: TRICKSTERS, DECONSTRUCTION, AND CHAOS AT WORK IN THE WHEDONVERSE by Brita Marie Graham A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English MONTANA STATE UNIVERSTIY Bozeman, Montana April 2007 © COPYRIGHT by Brita Marie Graham 2007 All Rights Reserved ii APPROVAL Of a thesis submitted by Brita Marie Graham This thesis has been read by each member of the thesis committee and has been found to be satisfactory regarding content, English usage, format, citations, bibliographic style, and consistency, and is ready for submission to the Division of Graduate Education. Dr. Linda Karell, Committee Chair Approved for the Department of English Dr. Linda Karell, Department Head Approved for the Division of Graduate Education Dr. Carl A. Fox, Vice Provost iii STATEMENT OF PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Montana State University, I agree that the Library shall make it availably to borrowers under rules of the Library. If I have indicated my intention to copyright this thesis by including a copyright notice page, copying is allowable only for scholarly purposes, consistent with “fair use” as prescribed in the U.S. Copyright Law. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this thesis in whole or in parts may be granted only by the copyright holder. Brita Marie Graham April 2007 iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In gratitude, I wish to acknowledge all of the exceptional faculty members of Montana State University’s English Department, who encouraged me along the way and promoted my desire to pursue a graduate degree. -

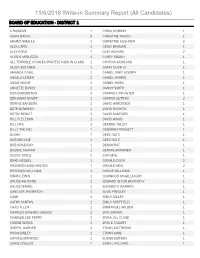

11/6/2018 Write-In Summary Report (All Candidates) BOARD of EDUCATION - DISTRICT 1

11/6/2018 Write-in Summary Report (All Candidates) BOARD OF EDUCATION - DISTRICT 1 A RAINEAR 1 CHRIS MURRAY 1 ADAM HATCH 2 CHRISTINE ASHOO 1 AHMED SMALLS 1 CHRISTINE KUSHNER 2 ALEX CARR 1 CINDY BEAMAN 1 ALEX FORD 1 CLAY WILKINS 2 ALICE E VERLEZZA 1 COREY BRUSH 1 ALL TERRIBLE CHOICES PROTECT KIDS IN CLASS 1 CYNTHIA WOOLARD 1 ALLEN BUTCHER 1 DAFFY DUCK III 1 AMANDA GOWL 1 DANIEL GREY SCURRY 1 ANGELA LEISER 2 DANIEL HARRIS 1 ANGIE WIGHT 1 DANIEL HORN 1 ANNETTE BUSBY 1 DANNY SMITH 1 BEN DOBERSTEIN 2 DAPHNE LANCASTER 1 BENJAMIN DOVER 1 DAPHNE SUTTON 2 BERNIE SANDERS 1 DAVID HARDISTER 1 BETH BOWMAN 1 DAVID RUNYON 1 BETSY BENOIT 1 DAVID SANFORD 1 BILL FLELEHAN 1 DAVID WOOD 1 BILL NYE 1 DEANNE TALLEY 1 BILLY THE KID 1 DEBORAH PRICKETT 1 BLANK 7 DEEZ NUTS 1 BOB MELONE 1 DEEZ NUTZ 1 BOB SPAZIANO 1 DEMOCRAT 1 BOBBIE CAVNAR 1 DENNIS BRAWNER 1 BOBBY JONES 1 DON MIAL 1 BRAD HESSEL 1 DONALD DUCK 2 BRANDON WASHINGTON 1 DONALD MIAL 2 BRANNON WILLIAMS 1 DONNE WILLIAMS 1 BRIAN LEWIS 1 DURWOOD MCGILLACUDY 1 BRUCE ASHFORD 1 EDWARD ALTON HUNTER IV 1 BRUCE MAMEL 1 ELIZABETH WARREN 1 CANDLER THORNTON 1 ELVIS PRESLEY 1 CASH 1 EMILY JOLLEY 1 CATHY SANTOS 1 EMILY SHEFFIELD 1 CHAD ALLEN 1 EMMANUEL WILDER 1 CHARLES EDWARD CHEESE 1 ERIC BROWN 1 CHARLES LEE PERRY 1 ERIKA JILL CLOSE 1 CHERIE WIGGS 1 ERIN E O'LEARY 1 CHERYL GARNER 1 ETHAN MATTHEWS 1 CHRIS BAILEY 1 ETHAN SIMS 1 CHRIS BJORNSTED 1 EUSHA BURTON 1 CHRIS COLLUM 1 EVAN L POLLARD 1 11/6/2018 Write-in Summary Report (All Candidates) BOARD OF EDUCATION - DISTRICT 1 EVERITT 1 JIMMY ALSTON 1 FELIX KEYES 1 JO ANNE -

An Analysis and Expansion of Queerbaiting in Video Games

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Cultural Analysis and Social Theory Major Research Papers Cultural Analysis and Social Theory 8-2018 Queering Player Agency and Paratexts: An Analysis and Expansion of Queerbaiting in Video Games Jessica Kathryn Needham Wilfrid Laurier University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cast_mrp Part of the Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, and the Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons Recommended Citation Needham, Jessica Kathryn, "Queering Player Agency and Paratexts: An Analysis and Expansion of Queerbaiting in Video Games" (2018). Cultural Analysis and Social Theory Major Research Papers. 6. https://scholars.wlu.ca/cast_mrp/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Cultural Analysis and Social Theory at Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cultural Analysis and Social Theory Major Research Papers by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Queering player agency and paratexts: An analysis and expansion of queerbaiting in video games by Jessica Kathryn Needham Honours Rhetoric and Professional Writing, Arts and Business, University of Waterloo, 2016 Major Research Paper Submitted to the M.A. in Cultural Analysis and Social Theory in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Master of Arts Wilfrid Laurier University 2018 © Jessica Kathryn Needham 2018 1 Abstract Queerbaiting refers to the way that consumers are lured in with a queer storyline only to have it taken away, collapse into tragic cliché, or fail to offer affirmative representation. Recent queerbaiting research has focused almost exclusively on television, leaving gaps in the ways queer representation is negotiated in other media forms. -

The Programme Typology and Its Association with the Study of Diversity and The

Fordham University Masthead Logo DigitalResearch@Fordham Donald McGannon Communication Research McGannon Center Working Paper Series Center 2-2011 The rP ogramme Typology and its Association with the Study of Diversity and the Audience Viewing Figures: The yT pological Strategy of the Greek Television Programme Andreas Masouras McGannon Center for Communication Research Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/mcgannon_working_papers Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons Recommended Citation Masouras, Andreas, "The rP ogramme Typology and its Association with the Study of Diversity and the Audience Viewing Figures: The yT pological Strategy of the Greek Television Programme" (2011). McGannon Center Working Paper Series. 29. https://fordham.bepress.com/mcgannon_working_papers/29 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Donald McGannon Communication Research Center at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in McGannon Center Working Paper Series by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE D O N A L D M C G ANNON C OMMUNICATION R E S E A R C H C ENTER W O R K I N G P APER T HE P ROGRAM ME T YPOLOGY AND ITS A SSOCIATION W I T H T H E S T U D Y O F D IVERSITY AND THE A U D I E N C E V I E W I N G F IGURES : T HE T YPOLOGICAL S TRATEGY OF T H E G R E E K T E L E V I S I O N P ROGRAMME Andreas Masouras Visiting Research Fellow Donald McGannon Communication Research Center February, 2011 Donald McGannon Communication Research Center Faculty Memorial Hall, 4 th f l . -

Genesis of the Bible Documentary: the Development of Religious Broadcasting in the UK

Genesis of the Bible documentary: the development of religious broadcasting in the UK Richard Wallis Introduction Television genres and sub-genres are rarely stable over time. The Bible documentary is a form of factual programme making that emerged recognizably during the 1970s, reflecting broader stylistic trends in television. Today more than ever, in a climate in which the stakes are high for the winning and retention of audiences, television commissioning editors are caught between a cultural aversion to risk-taking, and an ambition to claim the next big ‘genre-busting’ hit. The consequence of these contradictory pressures is that programme genres are not so much invented as developed through a process of cultivated adaptation and hybridity: a tendency towards small iterative changes. To a significant extent, the template for the modern ‘authored’ documentary remains the seminal Civilisation (BBC, 1969): art historian, Kenneth Clark’s personal view of the philosophy, art, and architecture of the Western world. The remarkable impact of this thirteen-part series is attributable, in part, to the erudition and urbane authority of its on-screen presenter (Clark was knighted for his achievements), and in part to its visual richness (being one of the first such series to be filmed in colour) establishing the lavish travelogue style. It was this approach that was repeated by Civilisation’s producer, Peter Montagnon, in his subsequent thirteen-part series The Long Search (BBC, 1977), written by the scholar Ninian Smart, which examined the world’s major religions. There are other reasons, however, why the documentary was embraced as a vehicle for religious programmes during the 1970s, and its particular history should be understood in Genesis of the Bible documentary: the development of religious broadcasting in the UK. -

The Role of Disability in Buffy the Vampire Slayer Amanda H

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by University of New Mexico University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Special Education ETDs Education ETDs 7-12-2014 The Role of Disability in Buffy the Vampire Slayer Amanda H. Heggen Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/educ_spcd_etds Recommended Citation Heggen, Amanda H.. "The Role of Disability in Buffy the Vampire Slayer." (2014). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ educ_spcd_etds/16 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Education ETDs at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Education ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Role of Disability in Buffy the Vampire Slayer i Amanda H. Heggen Candidate Special Education Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Dr. Julia Scherba de Valenzuela , Chairperson Dr. Susan Copeland Dr. James Stone Dr. David Witherington The Role of Disability in Buffy the Vampire Slayer ii THE ROLE OF DISABILITY IN BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER by AMANDA H. HEGGEN B.A. Psychology, Goshen College, 2001 M.A. Special Education, Univeristy of New Mexico, 2006 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Special Education The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico May, 2014 The Role of Disability in Buffy the Vampire Slayer iii Acknowledgements The list of people who have contributed to this dissertation in many forms, from much-needed pep talks to intensely brilliant advice on how to present my findings, is epic.