Hains Point) Washington D I 51- R 1 C T O ±" C O Li; Nib I A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

East-Download The

TIDAL BASIN TO MONUMENTS AND MUSEUMS Outlet Bridge TO FRANKLIN L’ENFANT DELANO THOMAS ROOSEVELT ! MEMORIAL JEFFERSON e ! ! George ! # # 14th STREET !!!!! Mason Park #! # Memorial MEMORIAL # W !# 7th STREET ! ! # Headquarters a ! te # ! r ## !# !# S # 395 ! t # !! re ^ !! e G STREET ! OHIO DRIVE t t ! ! # e I Street ! ! ! e ! ##! tr # ! !!! S # th !!# # 7 !!!!!! !! K Street Cuban ! Inlet# ! Friendship !!! CASE BRIDGE## SOUTHWEST Urn ! # M Bridge ! # a # ! # in !! ! W e A !! v ! e ! ! ! n ! ! u East Potomac !!! A e 395 ! !! !!!!! ^ ! Maintenance Yard !! !!! ! !! ! !! !!!! S WATERFRONT ! e ! !! v ! H 6 ri ! t ! D !# h e ! ! S ! y # I MAINE AVENUE Tourmobile e t George Mason k ! r ! c ! ! N e !! u ! e ! B East Potomac ! Memorial !!! !!! !! t !!!!! G Tennis Center WASHINGTON! !! CHANNEL I STREET ##!! !!!!! T !"!!!!!!! !# !!!! !! !"! !!!!!! O Area!! A Area B !!! ! !! !!!!!! N ! !! U.S. Park ! M S !! !! National Capital !!!!!#!!!! ! Police Region !!!! !!! O !! ! Headquarters Headquarters hi !! C !!!! o !!! ! D !!!!! !! Area C riv !!!!!!! !!!! e !!!!!! H !! !!!!! !!O !! !! !h ! A !! !!i ! ! !! !o! !!! Maine !!!D ! ! !!r !!!! # Lobsterman !!iv ! e !! N !!!!! !! Memorial ! ! !!" ! WATER STREET W !!! !! # ! ! N a ! ! ! t !! ! !! e !! ##! r !!!! #! !!! !! S ! ! !!!!!!! ! t !!! !! ! ! E r !!! ! !!! ! ! e !!!! ! !!!!!! !!! e ! #!! !! ! ! !!! t !!!!!#!! !!!!! BUCKEYE DRIVE Pool !! L OHIO #!DRIVE! !!!!! !!! #! !!! ! Lockers !!!## !! !!!!!!! !! !# !!!! ! ! ! ! !!!!! !!!! !! !!!! 395 !!! #!! East Potomac ! ! !! !!!!!!!!!!!! ! National Capital !!!! ! ! -

Potomac Flats.Pdf

Form 10-306 STATE: (Oct. 1972) NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NFS USE ONLY FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES ENTRY DATE (Type all entries - complete applicable sections) ———m COMMON: East and West Potomac Parks AND/OR HISTORIC: STREET AND NUMBER: area bounded by Constitution Avenue, 17th Street, Indepen dence Avenue, Washington Channel, Potomac River and Rock Creek Park CITY OR TOWN: CONGRESSIONAL ^ongressman Washington Walter E. Fauntroy, D.C. STATE: CODE COUNTY: District of Columbia 11 District of Columbia 001 CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC [X] District Q Building |XJ Public Public Acquisition: CD Occupied Yes: QSite CD Structure CD Private CD In Process I | Unoccupied I | Restricted CD Object CD Both I | Being Considered [ | Preservation work Qg) Unrestricted in progress LDNo PRESENT USE (Check One of More as Appropriate) I | Agricultural [XJ Government ffi Park 1X1 Transportation | | Commercial CD Industrial CD Private Residence CD Other (Specify) CD Educational CD Military [ | Religious I | Entertainment [~_[ Museum I | Scientific National Park Service, Department of the Interior REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: (If applicable) STREET AND NUMBER: National Capital Parks 1100 Ohio Drive, S.W. CITY OR TOWN: CODE Washington COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: None exists—parks are reclaimed land TITLE OF SURVEY: National Park Service survey in compliance with Executive Order 11593 DATE OF SURVEY: [29 Federal CD State CD County CD Local DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: 09 National Capital Parks STREET AND NUMBER: 1100 Ohio Drive, S.W. Cl TY OR TOWN: Washington District of Columbia 11 ©-©--- - - "- © - - _--_ -.- _---..-- . _ - B& Exc9\\en* [~~| Good- v'Q FVir - "^Q Deteriorated : - fH Ruins "-': - PI Unexposed : CONDWIOK -=."'-". -

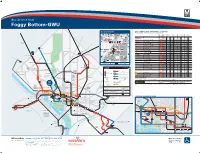

Bus Service from Foggy Bottom-GWU

Bus Service from Foggy Bottom-GWU Silver Spring BUS BOARDING MAP BUS SERVICE AND BOARDING LOCATIONS The table shows approximate minutes between buses; check schedules for full details 1/4 mile Best radius West End walking Branch Western MONDAY TO FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY distance Ritz-Carlton e Library v BOARD AT One A L St e L St Washington ir ROUTE DESTINATION BUS STOP AM RUSH MIDDAY PM RUSH EVENING DAY EVENING DAY EVENING t t h s S Eastern Ave S Avenue Pe Circle p George t t h n d m n t r t S s Suites y a S 4 Washington lv 3 a A H S METROBUS h 2 2 n d t t ia University A D n s 5 v e ew 2 1 2 Hospital N 2 The hington C 2 as ir 30N 30S 33 Friendship Heights m 10-20 10-20 7-15 15-30 10-20 15-30 10-20 15-30 Melrose J W CD George 30N 36 Naylor Rd m 15-25 20 15 15-30 20-30 20-30 30 30 29 K St Washington K St 29 BF Bethesda Statue C International 30S 32 Southern Ave m 15-25 20 10-15 15-30 20-30 20-30 20-40 20-40 Finance BF P Corporation t e B nn C s 31 Friendship Heights m 30 30 12-20 30 30 30 30 30 ylv Takoma s a DF nia w George Washington Western Ave Queen Annes Ln Av o University Hospital e n 31 32 36 Potomac Park 3-6 6-14 7-20 10-20 10-15 12-30 12-20 30 S I St E L1 Chevy Chase Circle F 33 Federal Triangle B 5-15 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 Georgia Ave I St e I St Military Rd v 38B Ballston-MU m 12-25 20 15 20-30 30 30 30 30 A Connecticut Ave Riggs Rd Foggy Bottom- CD re E 31 t GWU Inn hi S s GWU 38B Farragut N&W 12 20 9-15 20-30 30 30 30 30 33 h m Military Rd t mp 5 A a 80 2 Academic & Marvin 30N H Doubletree 16th St 14th St Fort Totten Galloway -

Building Stones of the National Mall

The Geological Society of America Field Guide 40 2015 Building stones of the National Mall Richard A. Livingston Materials Science and Engineering Department, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland 20742, USA Carol A. Grissom Smithsonian Museum Conservation Institute, 4210 Silver Hill Road, Suitland, Maryland 20746, USA Emily M. Aloiz John Milner Associates Preservation, 3200 Lee Highway, Arlington, Virginia 22207, USA ABSTRACT This guide accompanies a walking tour of sites where masonry was employed on or near the National Mall in Washington, D.C. It begins with an overview of the geological setting of the city and development of the Mall. Each federal monument or building on the tour is briefly described, followed by information about its exterior stonework. The focus is on masonry buildings of the Smithsonian Institution, which date from 1847 with the inception of construction for the Smithsonian Castle and continue up to completion of the National Museum of the American Indian in 2004. The building stones on the tour are representative of the development of the Ameri can dimension stone industry with respect to geology, quarrying techniques, and style over more than two centuries. Details are provided for locally quarried stones used for the earliest buildings in the capital, including A quia Creek sandstone (U.S. Capitol and Patent Office Building), Seneca Red sandstone (Smithsonian Castle), Cockeysville Marble (Washington Monument), and Piedmont bedrock (lockkeeper's house). Fol lowing improvement in the transportation system, buildings and monuments were constructed with stones from other regions, including Shelburne Marble from Ver mont, Salem Limestone from Indiana, Holston Limestone from Tennessee, Kasota stone from Minnesota, and a variety of granites from several states. -

Motorcoach Parking and Drop-Off/Pick-Up Locations

Motorcoach Parking and Drop-Off/Pick-Up Locations Number of Location Attraction Spaces Restrictions Cost Curbside Parking Locations 700-900 block Maine Avenue, SW Arena Stage/Waterfront 6 9:30am-4:00pm Mon-Fri: 4 hour limit Free 900-1200 block Maine Avenue, SW Arena Stage/Waterfront 4 No limit Free 1500 block Independence Avenue, Washington Monument 8 7:00am-6:30pm: 2 hour limit Free NW 200-400 block 15th Street, NW White House 5 7:00am-6:30pm: 2 hour limit Free 400 block New Jersey Avenue, NW Hyatt Regency 1 1 hour limit Free 3500 block Water St., NW Georgetown 4 No limit Free 1000 block 10th St, NW Souvenir City 1 7:00am-6:30pm: 1 hour limit Free Bus Parking Lot Locations $30/day Mon- Fri 6:00am-10:00pm in and out privileges $55 Sat-Sun and RFK Stadium, Lot 3, NE N/A 100 on weekdays only. Events Tel: (202) 608-1113 (Advance Purchase) or $60 day of. Union Station Parking Garage, NW N/A 20 7:00am-7:00pm Tel: (202) 430-2437 $20 per visit $20 up to 3 6:00am-6:00pm Monday-Friday Buzzard's Point Lot -1880 2nd St. SW N/A 80 hours/$50 per Tel: (202) 464-2900 day Hains Point/East Potomac Park, SW N/A 11 7:00am-6:00pm Free Off Street Parking at Tourist Sites Generally restricted to site visitors. Call Basilica of the National Shrine of the 400 Michigan Avenue, NE 100 for more information. Tel: (202) 526- Free Immaculate Conception 8300 Restricted to site visitors Tel: 1-800-967- 1411 W St, SE Frederick Douglass Memorial Home 3 Free 2283 Restricted to site visitors. -

Staff Recommendation

STAFF RECOMMENDATION NCPC File No. 7060 THE NATIONAL MALL NATIONAL MALL PLAN Washington, DC Submitted by the National Park Service November 23, 2010 Abstract The National Park Service has submitted the National Mall Plan for the management and stewardship of the land in its jurisdiction on the National Mall. The plan is a framework for future decision-making and implementation of physical improvements for the protection of the National Mall’s renowned natural and cultural resources, new visitor amenities and services, additional accommodations for First Amendment demonstrations and special events, better- linked circulation in a range of modes, accessibility throughout the Mall, additional opportunities for active and passive recreation, and improved visitor information and education. The National Park Service’s goal for the National Mall is that it be a model in sustainable urban park development, resource protection, and management. Commission Action Requested by Applicant Approval of the National Mall Plan, pursuant to 40 U.S.C. § 8722(b)(1) and (d)). Executive Director’s Recommendation The Commission: Approves the National Mall Plan, as shown on NCPC Map File No. 1.41(78.00)43205. Notes that: • The National Mall Plan is based on the Preferred Alternative presented and analyzed in the National Park Service’s Final Environmental Impact Statement, Record of Decision, and Section 106 Programmatic Agreement. NCPC File No. 7060 Page 2 • Additional compliance with the National Environmental Policy Act and the National Historic Preservation Act will be required for the development and implementation of many of the National Mall Plan’s proposed projects, and that the siting and design of individual projects are subject to the Commission’s review and approval. -

National Mall & Memorial Parks

COMPLIMENTARY $2.95 2017/2018 YOUR COMPLETE GUIDE TO THE PARKS NATIONAL MALL & MEMORIAL PARKS ACTIVITIES • SIGHTSEEING • DINING • LODGING TRAILS • HISTORY • MAPS • MORE OFFICIAL PARTNERS This summer, Yamaha launches a new Star motorcycle designed to help you journey further…than you ever thought possible. To see the road ahead, visit YamahaMotorsports.com/Journey-Further Some motorcycles shown with custom parts, accessories, paint and bodywork. Dress properly for your ride with a helmet, eye protection, long sleeves, long pants, gloves and boots. Yamaha and the Motorcycle Safety Foundation encourage you to ride safely and respect the environment. For further information regarding the MSF course, please call 1-800-446-9227. Do not drink and ride. It is illegal and dangerous. ©2017 Yamaha Motor Corporation, U.S.A. All rights reserved. BLEED AREA TRIM SIZE WELCOME LIVE AREA Welcome to our nation’s capital, Wash- return trips for you and your family. Save it ington, District of Columbia! as a memento or pass it along to friends. Zion National Park Washington, D.C., is rich in culture and The National Park Service, along with is the result of erosion, history and, with so many sites to see, Eastern National, the Trust for the National sedimentary uplift, and there are countless ways to experience Mall and Guest Services, work together this special place. As with all American to provide the best experience possible Stephanie Shinmachi. Park Network editions, this guide to the for visitors to the National Mall & Me- 8 ⅞ National Mall & Memorial Parks provides morial Parks. information to make your visit more fun, memorable, safe and educational. -

Potomac River Tidal Basin L'enfant Dev

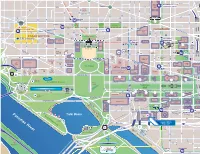

S S St. Matthew's S Cathedral 11th 11th Jefferson Pl 12th 10th Ridge St Morgan St Washington MT. VERNONONN SQ.S / 7THH ST- Thomas Circle Convention CONVENTIONON CENTERTE M St M St Center National Geographic Society P Desales St 17th St Sumner Row L St 16th St 16th 18th St 13th St 13th 14th St 15th St L St L St FARRAGUTRR NORTHRT Mt Vernon Washington Square t K St City Museum Circle McPherson FARRAGUTAR WESTT Farragut 4th St Square Square Franklin Park GW HOSPITAL I St I St (EYE) New York Ave CHINATOWN Massachusetts FOGGYFOO BOTTOM-OT GWU 20th St 19th St MCPHERSONRS Old Convention I St Pennsylvania SQUAREUAARE Center 25th St I St (closed) Ave 17th St 7th St H St 8th St Ave Decatur 9th St House H St FOGGY BOTTOM Jackson Pl Lafayette Square National Renwick Madison Pl Museum H St 15th St G.W. University Gallery of Women GALLERYYYP PL.-P General International in the Arts Accounting Monetary World METROTR Martin Luther King CHINATOWNOWNWNW Office Fund Bank CENNTTER Memorial Library 21st St 21st 24th St 23rd St G St 22nd St G St MCI CENTER Executive Jewish Office Building Treasury Historical Department St th National Building Society of 11 12th St St 10th Museum Greater Washington The White House National F St Octagon Law Enforcement Virginia Ave Theatre Warner Memorial General Museum Theatre Services Ford's Int'l Spy JUDDID ARY Admin Theatre Museum SSQ E Freedom E St E St Corcoran Plaza Gallery of Art Shakespeare Wilson J Edgar Hoover Theatre E St 8th St D St 5th St Building Building (FBI) 6th St Office of Personal White House Pennsylvania Ave Management Red Cross Visitor Center Int'l D St Navy Dept. -

Comments Received

PARKS & OPEN SPACE ELEMENT (DRAFT RELEASE) LIST OF COMMENTS RECEIVED Notes on List of Comments: ⁃ This document lists all comments received on the Draft 2018 Parks & Open Space Element update during the public comment period. ⁃ Comments are listed in the following order o Comments from Federal Agencies & Institutions o Comments from Local & Regional Agencies o Comments from Interest Groups o Comments from Interested Individuals Comments from Federal Agencies & Institutions United States Department of the Interior NATIONAL PARK SERVICE National Capital Region 1100 Ohio Drive, S.W. IN REPLY REFER TO: Washington, D.C. 20242 May 14, 2018 Ms. Surina Singh National Capital Planning Commission 401 9th Street, NW, Suite 500N Washington, DC 20004 RE: Comprehensive Plan - Parks and Open Space Element Comments Dear Ms. Singh: Thank you for the opportunity to provide comments on the draft update of the Parks and Open Space Element of the Comprehensive Plan for the National Capital: Federal Elements. The National Park Service (NPS) understands that the Element establishes policies to protect and enhance the many federal parks and open spaces within the National Capital Region and that the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC) uses these policies to guide agency actions, including review of projects and preparation of long-range plans. Preservation and management of parks and open space are key to the NPS mission. The National Capital Region of the NPS consists of 40 park units and encompasses approximately 63,000 acres within the District of Columbia (DC), Maryland, Virginia and West Virginia. Our region includes a wide variety of park spaces that range from urban sites, such as the National Mall with all its monuments and Rock Creek Park to vast natural sites like Prince William Forest Park as well as a number of cultural sites like Antietam National Battlefield and Manassas National Battlefield Park. -

Potomac Park

46 MONUMENTAL CORE FRAMEWORK PLAN EDAW Enhance the Waterfront Experience POTOMAC PARK Potomac Park can be reimagined as a unique Washington destination: a prestigious location extending from the National Mall; a setting of extraordinary beauty and sweeping waterfront vistas; an opportunity for active uses and peaceful solitude; a resource with extensive acreage for multiple uses; and a shoreline that showcases environmental stewardship. Located at the edge of a dense urban center, Potomac Park should be an easily accessible place that provides opportunities for water-oriented recreation, commemoration, and celebration in a setting that preserves the scenic landscape. The park offers great potential to relieve pressure on the historic and fragile open space of the National Mall, a vulnerable resource that is increasingly overburdened with demands for large public gatherings, active sport fields, everyday recreation, and new memorials. Potomac Park and its shoreline should offer a range of activities for the enjoyment of all. Some areas should accommodate festivals, concerts, and competitive recreational activities, while other areas should be quiet and pastoral to support picnics under a tree, paddling on the river, and other leisure pastimes. The park should be connected with the region and with local neighborhoods. MONUMENTAL CORE FRAMEWORK PLAN 47 ENHANCE THE WATERFRONT EXPERIENCE POTOMAC PARK Context Potomac Park is a relatively recent addition to Ohio Drive parallels the walkway, provides vehicular Washington. In the early years of the city it was an access, and is used by bicyclists, runners, and skaters. area of tidal marshes. As upstream forests were cut The northern portion of the island includes 25 acres and agricultural activity increased, the Potomac occupied by the National Park Service’s regional River deposited greater amounts of silt around the headquarters, a park maintenance yard, offices for the developing city. -

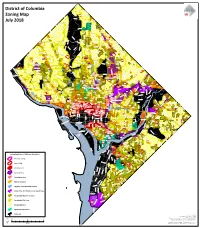

Pending Zoning Ac Ve PUD Pending PUD Campus Plans Downtown

East Beach Dr NW Beach North Parkway Portal District of Columbia Eastern Ave NW R-1-A Portal Dr NW Parkside Dr NW Kalmia Rd NW 97-16D Zoning Map 32nd St NW RA-1 12th St NW Wise Rd NW MU-4 R-1-B R-2 16th St NW R-2 76-3 Geranium St NW July 2018 Pinehurst Parkway Beech St NW Piney Branch Portal Aberfoyle Pl NW WR-1 RA-1 Alaska Ave NW WR-2 Takoma MU-4"M Worthington St NW WR-3 Dahlia St NW MU-4 WR-4 NC-2 R-1-A WR-6 RA-1 Utah Ave NW 31st Pl NW WR-6 MU-4 WR-5 RA-1 WR-7 Sherrill Dr NW WR-8 WR-3 MU-4 WR-5 Aspen St NW Nevada Ave NW Stephenson Pl NW Oregon Ave NW 30th St NW RA-2 4th St NW R-2 Van Buren St NW 2nd St NW Harlan Pl NW Pl Harlan R-1-B Broad Branch Rd NW Luzon Ave NW R-2 Pa�erson St NW Tewkesbury Pl NW 26th St NW R-1-B Chevy Tuckerman St NE Chase NW Pl 2nd Circle MU-3 Sheridan St NW Blair Rd NW Beach Dr NW R-3 MU-3 MU-3 MU-4 R-1-B Mckinley St NW Fort Circle Park 14th St NW Morrison St NW PDR-1 1st Pl NE 05-30 R-2 R-2 RA-1 MU-4 RA-4 Missouri Ave NW Peabody St NW Francis G. RA-1 04-06 Lega�on St NW Newlands Park RA-2 (Little Forest) Eastern Ave NE Morrow Dr NW RA-3 MU-7 Oglethorpe St NE Military Rd NW 2nd Pl NW 96-13 27th St NW Kanawha St NW Fort Slocum Friendship Heights Nicholson St NW Park MU-7 MU-5A R-2 R-2 "M Fort R-1-A NW St 9th Reno Rd NW Glover Rd NW Circle 85-20 R-3 Fort MU-4 R-2 NW St 29th Park MU-5A Circle Madison St NW MU-4 Park R-3 R-1-A RF-1 PDR-1 RA-2 R-8 RA-2 06-31A Fort Circle Park Linnean Ave NW R-16 MU-4 Rock Creek Longfellow St NW Kennedy St NE R-1-B RA-1 MU-4 RA-4 Ridge Rd NW Park & Piney MU-4 R-3 MU-4 Kennedy St NW -

WASHINGTON, D.C. Our Land, Our Water, Our Heritage

WASHINGTON, D.C. Our Land, Our Water, Our Heritage . LWCF Funded Places in Washington, D.C. LWCF Success in Washington, D.C. The Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) has provided funding to help protect some of Washington, D.C.’s most special places and ensure Federal Program recreational access for hiking, cycling, fishing and other outdoor Ford’s Theatre NHS activities. Washington, D.C. has received approximately $18 million in FDR Memorial LWCF funding over the past five decades, protecting places such as the National Capital Parks-East Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial, Mary McLeod Bethune NHS, and Mary McLeod Bethune NHS National Capital Parks-East. Federal Total $4,200,000 LWCF state assistance grants have further supported hundreds of projects across Washington, D.C.’s local parks including Mitchell Park State Program Playground, Randall Recreation Center, and the East Potomac Park Total State Grants $13,800,000 Swimming Pool. Total $18,000,000 Kenilworth Park and Aquatic Gardens Visitors and residents of Washington, D.C. experience the natural habitat of the area at the beautifully preserved Kenilworth Aquatic Gardens. This wetland helps mitigate pollution, reduces flood damage, and alleviates risks from climate change. As part of the National Capital Parks East, this park which has hiking trails, boardwalks, and comprehensive environmental education resources, has received a portion of the $2.5 million of LWCF awarded to the District’s network of parks. In addition to many events over the year, members of the D.C. Garden Club plant thousands of lotus each spring, a one-of-a-kind spectacle that draws visitors from across town and around the world.