The Doctrinal Development of Fcd Wyneken and Its

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Father from Afar: Wilhelm Loehe and Concordia Theological Seminary in Fort Wayne Jsunes L

CONCORDIA THEOLOGICAL QUARTERLY Volume 60: Numbas 1-2 JANUARY-APRIL 1996 The: Anniversary of Concordia Theological Seminary Walter A. Maier ....................................................................... Concordia Theological Seminary: Reflections on Its On(:-Hundred-and-Fiftieth Anniversary at the Threshold of the Third Millennium Dean 0. Wenthe ...................................................................... Celebrating Our Heritage Cameron A. MacKenzie .......................................................... F. C. D. Wyneken: Motivator for the Mission Norman J. Threinen ................................................................. Father from Afar: Wilhelm Loehe and Concordia Theological Seminary in Fort Wayne Jsunes L. Schaaf ....................................................................... Tht: Protoevangelium and Concordia Theological Seminary Dlouglas McC. L. Judisch ........................................................ Prtlach the Word! The he-Hundred-and-Fiftieth Anniversary Hymn ................ Coinfessional Lutheranism in Eighteenth-Century Germany Vernon P. Kleinig .................................................................... Book Reviews ......................................................................127 Indices to Volume 59 (1995) Index of Authors and Editors .......................... ........................ 153 Index of Titles .......................................................................... 154 Index of Book Reviews ........................................................ -

Concordia Journal | Summer 2011 | Volume 37 | Number 3

Concordia Seminary Concordia Journal 801 Seminary Place St. Louis, MO 63105 COncordia Summer 2011 Journal volume 37 | number 3 Summer 2 01 1 volume 37 | number Was Walther Waltherian? Walther and His Manuscripts: Archiving Missouri’s Most Enduring Writer 3 A Bibliography of C. F. W. Walther’s Works in English COncordia 22ND ANNUAL Journal (ISSN 0145-7233) publisher Faculty Dale A. Meyer David Adams Erik Herrmann Victor Raj President Charles Arand Jeffrey Kloha Paul Robinson Theological Andrew Bartelt R. Reed Lessing Robert Rosin Executive EDITOR Joel Biermann David Lewis Timothy Saleska William W. Schumacher Gerhard Bode Richard Marrs Leopoldo Sánchez M. Dean of Theological Kent Burreson David Maxwell David Schmitt Research and Publication William Carr, Jr. Dale Meyer Bruce Schuchard SymposiumAT CONCORDIA SEMINARY EDITOR Anthony Cook Glenn Nielsen William Schumacher Travis J. Scholl Timothy Dost Joel Okamoto William Utech Managing Editor of Thomas Egger Jeffrey Oschwald James Voelz Theological Publications Jeffrey Gibbs David Peter Robert Weise September 20-21, 2011 Bruce Hartung Paul Raabe EDITORial assistant Melanie Appelbaum Exclusive subscriber digital access All correspondence should be sent to: via ATLAS to Concordia Journal & assistants CONCORDIA JOURNAL Concordia Theology Monthly: Carol Geisler 801 Seminary Place http://search.ebscohost.com Theodore Hopkins St. Louis, Missouri 63105 User ID: ATL0102231ps Melissa LeFevre 314-505-7117 Password: subscriber Technical problems? Matthew Kobs cj @csl.edu Email [email protected] Issued by the faculty of Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, Missouri, the Concordia Journal is the successor of Lehre und Wehre (1855-1929), begun by C. F. W. Walther, a founder of The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod. -

Lutherans for Lent a Devotional Plan for the Season of Lent Designed to Acquaint Us with Our Lutheran Heritage, the Small Catechism, and the Four Gospels

Lutherans for Lent A devotional plan for the season of Lent designed to acquaint us with our Lutheran heritage, the Small Catechism, and the four Gospels. Rev. Joshua V. Scheer 52 Other Notables (not exhaustive) The list of Lutherans included in this devotion are by no means the end of Lutherans for Lent Lutheranism’s contribution to history. There are many other Lutherans © 2010 by Rev. Joshua V. Scheer who could have been included in this devotion who may have actually been greater or had more influence than some that were included. Here is a list of other names (in no particular order): Nikolaus Decius J. T. Mueller August H. Francke Justus Jonas Kenneth Korby Reinhold Niebuhr This copy has been made available through a congregational license. Johann Walter Gustaf Wingren Helmut Thielecke Matthias Flacius J. A. O. Preus (II) Dietrich Bonheoffer Andres Quenstadt A.L. Barry J. Muhlhauser Timotheus Kirchner Gerhard Forde S. J. Stenerson Johann Olearius John H. C. Fritz F. A. Cramer If purchased under a congregational license, the purchasing congregation Nikolai Grundtvig Theodore Tappert F. Lochner may print copies as necessary for use in that congregation only. Paul Caspari August Crull J. A. Grabau Gisele Johnson Alfred Rehwinkel August Kavel H. A. Preus William Beck Adolf von Harnack J. A. O. Otteson J. P. Koehler Claus Harms U. V. Koren Theodore Graebner Johann Keil Adolf Hoenecke Edmund Schlink Hans Tausen Andreas Osiander Theodore Kliefoth Franz Delitzsch Albrecht Durer William Arndt Gottfried Thomasius August Pieper William Dallman Karl Ulmann Ludwig von Beethoven August Suelflow Ernst Cloeter W. -

Charles Porterfield Krauth: the American Chemnitz

The 37th Annual Reformation Lectures Reformation Legacy on American Soil Bethany Lutheran College S. C. Ylvisaker Fine Arts Center Mankato, Minnesota October 28-29, 2004 Lecture Number Three: Charles Porterfield Krauth: The American Chemnitz The Rev. Prof. David Jay Webber Ternopil’, Ukraine Introduction C. F. W. Walther, the great nineteenth-century German-American churchman, has some- times been dubbed by his admirers “the American Luther.”1 While all comparisons of this nature have their limitations, there is a lot of truth in this appellation. Walther’s temperament, his lead- ership qualities, and especially his theological convictions would lend legitimacy to such a de- scription. Similarly, we would like to suggest that Charles Porterfield Krauth, in light of the unique gifts and abilities with which he was endowed, and in light of the thoroughness and balance of his mature theological work, can fittingly be styled “the American Chemnitz.” Krauth was in fact an avid student of the writings of the Second Martin, and he absorbed much from him in both form and substance. It is also quite apparent that the mature Krauth always attempted to follow a noticeably Chemnitzian, “Concordistic” approach in the fulfillment of his calling as a teacher of the church in nineteenth-century America. We will return to these thoughts in a little while. Be- fore that, though, we should spend some time in examining Krauth’s familial and ecclesiastical origins, and the historical context of his development as a confessor of God’s timeless truth. Krauth’s Origins In the words of Walther, Krauth was, without a doubt, the most eminent man in the English Lutheran Church of this country, a man of rare learning, at home no less in the old than in modern theology, and, what is of greatest import, whole-heartedly devoted to the pure doctrine of our Church, as he had learned to understand it, a noble man and without guile.2 But Krauth’s pathway to this kind of informed Confessionalism was not an easy one. -

December 1987

FOREWORD In this issue of the Quarterly the sermon by Pastor David Haeuser emphasizes that the proclamation of sin and grace must never be relegated to the back- ground, but must always be in the forefront of all of our church work. Rev. Haeuser is pastor of Christ Lutheran Church, Belle Gardens, California and also director of Project Christo Rey, a Hispanic mission in that area. The article by Pastor Herbert Larson on THE CENTEN- NIAL OF WALTHER'S DEATH is both interesting and timely. Pastor Larson shows from the history of the Norwegian Synod that there existed a warm and cordial relation- ship between Dr. Walther and the leaders of the Synod, and that we as a Synod are truly indebted to this man of God. Rev. Larson is pastor of Faith Lutheran Church, San Antonio, Texas. As the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA) officially comes into existence on January 1, 1988, our readers will appreciate David Jay ~ebber'sresearch into the writings of some of the theologians of this new merger wherein he clearly shows that these teach- ings are un-Lutheran. David Webber was raised in the LCA and is presently a senior seminarian at Concordia Seminary, Fort Wayne, Indiana. An exegetical treatment of Romans 7: 14-25 by Professor Daniel Metzger explains the nature of the paradox in this section of Holy Scripture. Professor Metzger teaches religion and English at Bethany Lutheran College. He is currently on a sabbatical working on his doctorate. We also take this opportunity to wish our readers a blessed Epiphany and a truly happy and healthy New Year in the Name of the Christ-Child in whom alone we have lasting peace and joy. -

Wyneken As Missionary: Mission in the Life & Ministry of Friedrich

Let Christ Be Christ: Theology, Ethics & World Religions in the Two Kingdoms. Daniel N. Harmelink, ed. Huntington Beach, CA: Tentatio Press, 1999. 321-340. ©1999 Tentatio Press Wyneken as Missionary Mission in the Life & Ministry of Friedrich Conrad Dietrich Wyneken Robert E. Smith The mission theology of this pioneering nineteenth century figure of the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod is documented and analyzed, emphasizing F.C.D. Wyneken’s masterful approach to planting churches among German immigrants in North America. If C.F.W. Walther was the mind of first generation Missouri Synod Lutheranism, Friedrich Conrad Dietrich Wyneken was its heart and soul. One hundred years after fellow Hannoverian Henry Muhlenberg brought together the pastors and congregations of colonial America, Wyneken gathered scattered German Protestants into confessional Lutheran congregations and forged them into a closely knit family of churches. His missionary experience, method and plan would influence American Lutheran missions for many years to come. His zeal for God's mission still burns brightly in the heart of Missouri's compassion for the lost. Aptly, he is called the "thunder after the lightning:"1 German Immigrants & the American Frontier Eager and strong, confident and bold, the young United States of America surged into the western lands that opened before it. Vast, ancient forests and wide prairies promised fertile lands. Trails were blazed, canals dug, roads built and railroads forged to hasten the path to a land that seemed like Eden. Warm California and cool Colorado called out to adventurers seeking silver and gold. On the endless frontier, settlers found a chance to do well in life. -

P.4 Walther and the Formation of the Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod - P.7 C

For the LIFE of the WOROctober 2003. Volume Seven, Num LDber Four Walther as Churchman - p.4 Walther and the Formation of The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod - p.7 C. F. W. Walther—Pastor and Preacher - p.10 Called to Serve - p. 14 FROM THE PRES IDENT Dear Friends of Concordia Theological Seminary: For All the Saints Who Have Gone Before Us—C. F. W. Walther “ have been reminded of your sincere faith, which first lived in ages. Already in his university training in Germany he resisted Iyour grandmother Lois and in your mother Eunice and, I am the pervasive influences of rationalism. His classic treatise on persuaded, now lives in you also.” 2 Timothy 1:5 “The Proper Distinction Between Law and Gospel” and his work One of the beauties of the Christian church is its continuity on “Church and Ministry” have guided generations of Lutheran across generations. Already in Sacred Scripture Abraham, pastors. Less well known, but a tribute to Walther’s balance and Pastoral Theology Moses, David, Hannah, Esther, and numerous others are recom - deeply pastoral wisdom, is his . In the com - Pastoral Theology mended as models for faith and life. This continuity of the plete German version of , the breadth of church’s confession is attested by Paul’s journey to confer with Walther’s knowledge is evidenced as well as his commitment to St. Peter: “Then after three years, I went up to Jerusalem to get apply that theology to the life of the church. Encyclopedia of the Lutheran Church acquainted with Peter and stayed with him fifteen days” (Gala - In the , Vol. -

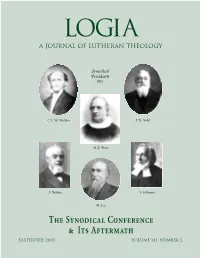

Logia 4/03 Text W/O

Logia a journal of lutheran theology Synodical Presidents C. F. W. Walther J. H. Sieker H. A. Preus J. Bading F. Erdmann M. Loy T S C I A eastertide 2003 volume xii, number 2 ei[ ti" lalei', wJ" lovgia Qeou' logia is a journal of Lutheran theology. As such it publishes articles on exegetical, historical, systematic, and liturgical theolo- T C A this issue shows the presidents of gy that promote the orthodox theology of the Evangelical the synods that formed the Evangelical Lutheran Lutheran Church. We cling to God’s divinely instituted marks of Synodical Conference (formed July at the church: the gospel, preached purely in all its articles, and the Milwaukee, Wisconsin). They include the sacraments, administered according to Christ’s institution. This Revs. C. F. W. Walther (Missouri), H. A. Preus name expresses what this journal wants to be. In Greek, LOGIA (Norwegian), J. H. Sieker (Minnesota), J. Bading functions either as an adjective meaning “eloquent,”“learned,” or (Wisconsin), M. Loy (Ohio), F. Erdmann (Illinois). “cultured,” or as a plural noun meaning “divine revelations,” “words,”or “messages.”The word is found in Peter :, Acts :, Pictures are from the collection of Concordia oJmologiva and Romans :. Its compound forms include (confes- Historical Institute, Rev. Mark A. Loest, assistant ajpologiva ajvnalogiva sion), (defense), and (right relationship). director. Each of these concepts and all of them together express the pur- pose and method of this journal. LOGIA considers itself a free con- ference in print and is committed to providing an independent L is indexed in the ATLA Religion Database, published by the theological forum normed by the prophetic and apostolic American Theological Library Association, Scriptures and the Lutheran Confessions. -

HHJ Bl Liicmnnniu) a SALUTARY INFLUENCE

HHJ Bl liicmnnniu) A SALUTARY INFLUENCE: GETTYSBURG COLLEGE, 1832-1985 Volume 1 Charles H. Glatfelter Gettysburg College Gettysburg, Pennsylvania 1987 Copyright © 1987 by Gettysburg College Allrights reserved. No part of this book may be used or repro- duced in any manner without written permission except in the case of brief quotations incritical articles or reviews. Printed inthe United States of America byW &MPrinting,Inc. Design and typography by C & J Enterprises, Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania The College Seal, 1832-1921 From an 1850 deed Contents Illustrations and Maps viii Tables ix Preface xi 1. The Background of Gettysburg College (1776-1832) 3 July 4, 1832 3 Two Colleges for Southcentral Pennsylvania 6 Lutheran Ministerial Training 13 Samuel Simon Schmucker 16 Gettysburg and the Lutheran Theological Seminary 22 Classical School and Gymnasium (1827-1832) 26 Pennsylvania College of Gettysburg (1831-1832) 32 2. Acquiring a Proper College Edifice (1832-1837) 41 Getting the Money 41 Building 58 3. After the Manner of a Well-Regulated Family (1832 1868) 73 Trustees 75 Finances 81 Presidents and Faculty 92 The Campus 104 Preparatory Department 119 Curriculum 122 Library 135 Equipment 139 The Medical Department 141 Students 146 Student Organizations 159 Alumni Association 167 Town and Gown 169 The College and the Lutheran Church 173 In the World of Higher Education 180 The Civil War 191 Changing the Guard 190 4. A Wider Place for a Greater Work (1868-1904) 193 Trustees 195 Finances 207 Presidents and Faculty 222 The Campus 242 Preparatory -

\200\200The American Recension of the Augsburg Confession

The American Recension of the Augsburg Confession and its Lessons for Our Pastors Today David Jay Webber Samuel Simon Schmucker Charles Philip Krauth John Bachman William Julius Mann Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod Evangelical Lutheran Synod Arizona-California District Pastors Conference West Coast Pastors Conference October 20-22, 2015 April 13 & 15, 2016 Green Valley Lutheran Church Our Redeemer Lutheran Church Henderson, Nevada Yelm, Washington In Nomine Iesu I. Those creeds and confessions of the Christian church that are of enduring value and authority emerged in crucibles of controversy, when essential points of the Christian faith, as revealed in Scripture, were under serious attack. These symbolical documents were written at times when the need for a faithful confession of the gospel was a matter of spiritual life or death for the church and its members. For this reason those symbolical documents were thereafter used by the orthodox church as a normed norm for instructing laymen and future ministers, and for testing the doctrinal soundness of the clergy, with respect to the points of Biblical doctrine that they address. The ancient Rules of Faith of the post-apostolic church, which were used chiefly for catechetical instruction and as a baptismal creed, existed in various regional versions. The version used originally at Rome is the one that has come down to us as the Apostles’ Creed. These Rules of Faith were prepared specifically with the challenge of Gnosticism in view. As the Apostles’ Creed in particular summarizes the cardinal articles of faith regarding God and Christ, it emphasizes the truth that the only God who actually exists is the God who created the earth as well as the heavens; and the truth that God’s Son was truly conceived and born as a man, truly died, and truly rose from the grave. -

Forming Servants in Who Teach the Faithful, Reach the Lost, and Care for All

CONCORDIA THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY 2014-2015Fort Academic Wayne, CatalogIndiana Forming servants in Jesus Christ who teach the faithful, reach the lost, and care for all. Notes for Christ in the Classroom and Community: The citation for the quote on pages 13-14 is from Robert D. Preus, The Theology of Post-Reformation Lutheranism, vol. 1 (St. Louis: Concordia, 1970), 217. Excerpts from Arthur A. Just Jr., “The Incarnational Life,” and Pam Knepper, “Kramer Chapel: The Jewel of the Seminary,” (For the Life of the World, June 1998) were used in this piece. Concordia Theological Seminary, Fort Wayne Academic Catalog 2014-2015 CONTENTS Christ in the Classroom and Community...................5 From the President ..................................15 Academic Calendar .................................16 History ..........................................19 Mission Statement/Introduction ........................ 20 Buildings and Facilities .............................. 24 Faculty/Boards.....................................26 Academic Programs .................................37 Academic Policies and Information .....................90 Seminary Community Life ........................... 104 Financial Information............................... 109 Course Descriptions ................................ 118 Campus Map ..................................... 184 Index ........................................... 186 This catalog is a statement of the policies, personnel and financial arrangements of Concordia Theological Seminary as projected by the responsible -

Jesus Thy Blood and Righteousness My Beauty Are My Glorious Dress

Jesus Thy Blood and Righteousness My Beauty Are My Glorious Dress A Series of Newsletter Articles written for the Bicentennial of the Birth of Carl Ferdinand Wilhelm Walther 1811-1887 by Pastor Don Hougard Benediction Lutheran Church Milwaukee, WI January 2011 Newsletter Article – Biography of CFW Walther “Remember your leaders who spoke the word of God to you. Consider the outcome of their way of life and imitate their faith. (Hebrews 13:7) 2011 is the two-hundredth anniversary of the birth of Carl Ferdinand Wilhelm Walther (October 25, 1811 – May 7, 1887) He was the first president of the Lutheran Church - Missouri Synod and is still the most influential pastor and theologian of our church body. This year I will be dedicating each of my newsletter articles to some aspect of his life and/or teaching. There is still much that Walther has to say to us today, even 200 years after his birth. CFW Walther was born in the village of Langenchursdorf in a part of Germany known as Saxony. His father and grandfather were pastors in Langenchursdorf, and his great grandfather was also a pastor. His childhood built a foundation of faith in God’s grace and mercy in Jesus Christ. At the age of three his father gave him a three-penny piece for learning this hymn verse: Jesus, thy blood and righteousness My beauty are, my glorious dress; Wherin before my God I’ll stand When I shall reach the heavenly land.1 Ferdinand went off to boarding school as a young boy. During that time Rationalism was broadly accepted in the German lands.