Miami and the State of Low- and Middle-Income Housing Executive Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

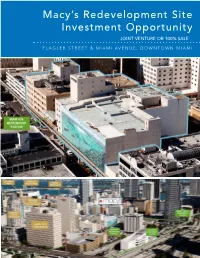

Macy's Redevelopment Site Investment Opportunity

Macy’s Redevelopment Site Investment Opportunity JOINT VENTURE OR 100% SALE FLAGLER STREET & MIAMI AVENUE, DOWNTOWN MIAMI CLAUDE PEPPER FEDERAL BUILDING TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 PROPERTY DESCRIPTION 13 CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT OVERVIEW 24 MARKET OVERVIEW 42 ZONING AND DEVELOPMENT 57 DEVELOPMENT SCENARIO 64 FINANCIAL OVERVIEW 68 LEASE ABSTRACT 71 FOR MORE INFORMATION, CONTACT: PRIMARY CONTACT: ADDITIONAL CONTACT: JOHN F. BELL MARIANO PEREZ Managing Director Senior Associate [email protected] [email protected] Direct: 305.808.7820 Direct: 305.808.7314 Cell: 305.798.7438 Cell: 305.542.2700 100 SE 2ND STREET, SUITE 3100 MIAMI, FLORIDA 33131 305.961.2223 www.transwestern.com/miami NO WARRANTY OR REPRESENTATION, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, IS MADE AS TO THE ACCURACY OF THE INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN, AND SAME IS SUBMITTED SUBJECT TO OMISSIONS, CHANGE OF PRICE, RENTAL OR OTHER CONDITION, WITHOUT NOTICE, AND TO ANY LISTING CONDITIONS, IMPOSED BY THE OWNER. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY MACY’S SITE MIAMI, FLORIDA EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Downtown Miami CBD Redevelopment Opportunity - JV or 100% Sale Residential/Office/Hotel /Retail Development Allowed POTENTIAL FOR UNIT SALES IN EXCESS OF $985 MILLION The Macy’s Site represents 1.79 acres of prime development MACY’S PROJECT land situated on two parcels located at the Main and Main Price Unpriced center of Downtown Miami, the intersection of Flagler Street 22 E. Flagler St. 332,920 SF and Miami Avenue. Macy’s currently has a store on the site, Size encompassing 522,965 square feet of commercial space at 8 W. Flagler St. 189,945 SF 8 West Flagler Street (“West Building”) and 22 East Flagler Total Project 522,865 SF Street (“Store Building”) that are collectively referred to as the 22 E. -

Miami-Dade County Commission on Ethics and Public Trust

Biscayne Building 19 West Flagler Street Miami-Dade County Suite 220 Miami, Florida 33130 Commission on Ethics Phone: (305) 579-2594 Fax: (305) 579-2656 and Public Trust Memo To: Mike Murawski, independent ethics advocate Cc: Manny Diaz, ethics investigator From: Karl Ross, ethics investigator Date: Nov. 14, 2007 Re: K07-097, ABDA/ Allapattah Construction Inc. Investigative findings: Following the June 11, 2007, release of Audit No. 07-009 by the city of Miami’s Office of Independent Auditor General, COE reviewed the report for potential violations of the Miami-Dade ethics ordinance. This review prompted the opening of two ethics cases – one leading to a complaint against Mr. Sergio Rok for an apparent voting conflict – and the second ethics case captioned above involving Allapattah Construction Inc., a for-profit subsidiary of the Allapattah Business Development Authority. At issue is whether executives at ABDA including now Miami City Commissioner Angel Gonzalez improperly awarded a contract to Allapattah Construction in connection with federal affordable housing grants awarded through the city’s housing arm, the Department of Community Development. ABDA is a not-for-profit social services agency, and appeared to pay itself as much as $196,000 in profit and overhead in connection with the Ralph Plaza I and II projects, according to documents obtained from the auditor general. The city first awarded federal Home Investment Partnership Program (HOME) funds to ABDA on April 15, 1998, in the amount of $500,000 in connection with Ralph Plaza phase II. On Dec. 17, 2002, the city again awarded federal grant monies to ABDA in the amount of $730,000 in HOME funds for Ralph Plaza phase II. -

Southern District of Florida Certified Mediator List Adelso

United States District Court - Southern District of Florida Certified Mediator List Current as of: Friday, March 12, 2021 Mediator: Adelson, Lori Firm: HR Law PRO/Adelson Law & Mediation Address: 401 East Las Olas Blvd. Suite 1400 Fort Lauderdale, FL 33301 Phone: 954-302-8960 Email: [email protected] Website: www.HRlawPRO.com Specialty: Employment/Labor Discrimination, Title Vll, FCRA Civil Rights, ADA, Title III, FMLA, Whistleblower, Non-compete, business disputes Locations Served: Broward, Indian River, Martin, Miami, Monroe, Palm Beach, St. Lucie Mediator: Alexander, Bruce G. Firm: Ciklin Lubitz Address: 515 N. Flagler Drive, 20th Floor West Palm Beach, FL 33401 Phone: 561-820-0332 Fax: 561-833-4209 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ciklinlubitz.com Languages: French Specialty: Construction Locations Served: Broward, Highlands, Indian River, Martin, Miami, Monroe, Okeechobee, Palm Beach, St. Lucie Mediator: Arrizabalaga, Markel Firm: K&A Mediation/Kleinman & Arrizabalaga, PA Address: 169 E. Flagler Street #1420 Miami, FL 33131 Phone: 305-377-2728 Fax: 305-377-8390 Email: [email protected] Website: www.kamediation.com Languages: Spanish Specialty: Personal Injury, Insurance, Commercial, Property Insurance, Medical Malpractice, Products Liability Locations Served: Broward, Miami, Palm Beach Page 1 of 24 Mediator: Barkett, John M. Firm: Shook Hardy & Bacon LLP Address: 201 S. Biscayne Boulevard Suite 2400 Miami, FL 33131 Phone: 305-358-5171 Fax: 305-358-7470 Email: [email protected] Specialty: Commercial, Environmental, -

English 3/21

MIAMI-DADE PUBLIC LIBRARY SYSTEM & Municipal Library Partners www.mdpls.org Branch Addresses and Hours Email: [email protected] Operating Hours (Unless otherwise indicated) Monday - Thursday 9:30 a.m. - 8:00 p.m. • Friday & Saturday 9:30 a.m. - 6:00 p.m. • Sunday - Closed 1 ALLAPATTAH 25 MAIN LIBRARY (DOWNTOWN) OUTREACH SERVICES 1799 NW 35 St. · 305.638.6086 101 West Flagler St. · 305.375.2665 Mon. - Sat. 9:30 a.m. - 6:00 p.m. | Sun. Closed CONNECTIONS 2 ARCOLA LAKES Home Library Services 8240 NW 7 Ave. · 305.694.2707 26 MIAMI BEACH REGIONAL 305.474.7251 227 22nd St. · 305.535.4219 3 BAY HARBOR ISLANDS STORYTIME EXPRESS 1175 95 St. · 786.646.9961 27 MIAMI LAKES Literacy Kits for 6699 Windmill Gate Rd. · 305.822.6520 Early Education Centers 4 CALIFORNIA CLUB 305.375.4116 700 Ives Dairy Rd. · 305.770.3161 28 MIAMI SPRINGS 401 Westward Dr. · 305.805.3811 MOBILE LIBRARY SERVICES 5 CIVIC CENTER PORTA KIOSK 305.480.1729 Metrorail Civic Center Station · 29 MODEL CITY (CALEB CENTER) 305.324.0291 2211 NW 54 St. · 305.636.2233 BRAILLE & TALKING BOOKS Mon. - Fri. 7:00 a.m. - 6:00 p.m. Mon. - Sat. 9:30 a.m. - 6:00 p.m. | Sun. Closed 305.751.8687 · 800.451.9544 Sat. & Sun. Closed 30 NARANJA 6 COCONUT GROVE 14850 SW 280 St. · 305.242.2290 TDD SYSTEM WIDE 2875 McFarlane Rd. · 305.442.8695 (TELECOMMUNICATIONS DEVICE 31 NORTH CENTRAL FOR THE DEAF) 7 CONCORD (CLOSED FOR RENOVATIONS) Florida Relay Service - 711 3882 SW 112 Ave. -

COMMUNITY RESOURCE GUIDE Miami-Dade County Homeless Trust Community Resource Guide Table of Contents

MIAMI-DADE COUNTY HOMELESS TRUST COMMUNITY RESOURCE GUIDE Miami-Dade County Homeless Trust Community Resource Guide Table of Contents Adults & Families Animal Care Services 3 Dental Services 3 Food Assistance 4 Clothing 11 Counseling 14 Domestic Violence & Sexual Violence Supportive Services 17 Employment/Training 18 HIV/AIDS Supportive Services 27 Immigration Services 27 Legal Services 28 Low-Cost Housing 29 Medical Care: Hospitals, Urgent Care Centers and Clinics 32 Mental Health/Behavioral Health Care 39 Shelter 42 Social Security Services 44 Substance Abuse Supportive Services 44 Elderly Services 45 Persons with Disabilities 50 2 Adults & Families Animal Care Animal Welfare Society of South Florida 2601 SW 27th Ave. Miami, FL 33133 305-858-3501 Born Free Shelter 786-205-6865 The Cat Network 305-255-3482 Humane Society of Greater Miami 1601 West Dixie Highway North Miami Beach, FL 33160 305-696-0800 Miami-Dade County Animal Services 3599 NW 79th Ave. Doral, FL 33122 311 Paws 4 You Rescue, Inc. 786-242-7377 Dental Services Caring for Miami Project Smile 8900 SW 168th St. Palmetto Bay, FL 33157 786-430-1051 Community Smiles Dade County 750 NW 20th St., Bldg. G110 Miami, FL 33127 305-363-2222 3 Food Assistance Camillus House, Inc. (English, Spanish & Creole) 1603 NW 7th Ave. Miami, FL 33136 305-374-1065 Meals served to community homeless Mon. – Fri. 6:00 AM Showers to community homeless Mon. – Fri. 6:00 AM Emergency assistance with shelter, food, clothing, job training and placement, residential substance abuse treatment and aftercare, behavioral health and maintenance, health care access and disease prevention, transitional and permanent housing (for those who qualify), crisis intervention and legal services. -

Miami New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 4Q18

Miami New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 4Q18 ID PROPERTY UNITS 3 CAOBA 444 41 4 Plaza Pointe 71 155 5 Muze at Met Square 391 7 Lazul 349 171 175 8 Riverview One 100 9 District West Gables Phase II 221 183 184 15 10 Panorama Tower 821 58 Total Lease-Up 2,397 44 26 182 179 124 11 Plaza Coral Gables, The 174 48 13 Gables Station 499 17 75 14 Liberty Square Phase IA 204 34 49 130 15 Midtown 6 447 178 116 113 16 Soleste Alameda 310 76 180 60 17 Bradley, The 175 101 112 18 Belle Isle Key 172 174 74 19 Overture at Downtown Doral South 193 172 177 73 127 61 20 Art Plaza 667 181 176 4 115 125 21 Soleste Twenty2 338 170 23 Century Parc Place 230 199 100 47 126 59 25 5250 Park 231 201 26 AMLI Chiquita 512 190 20 129 63 27 Megacenter Brickell 57 187 114 7 131 28 Henry, The 120 31 197 186 105 128 64 30 SoLe Mia 397 173 133 62 31 River Landing 507 169 103 193 82 3 32 Residence at University City, The 187 72 55 33 MB Station 190 203 195 80 34 Wynwood 25 289 191 83 210 85 198 121 132 30 35 Soleste Blue Lagoon 330 50 134 36 Cassa Grove 130 202 192 205 38 Oasis at Blue Lagoon 272 206 8 188 40 Triton Center 325 79 106 41 Quadro 198 209 200 196 77 57 42 Las Vistas at Amelia 174 228 204 81 5 42 44 Midtown 8 387 84 189 104 65 45 Columbus, The 72 194 109 45 47 Gardens Park Phase II 71 207 211 238 135 48 Biscayne 27 330 27 102 123 157 49 Modera Edgewater 297 208 78 50 Park - Line MiamiCentral 816 185 52 Grand Doral 80 53 10 240 53 Maizon at Brickell 262 54 Aura, The 100 239 237 Total Under Construction 9,743 55 Lucida Palmetto 108 236 56 East 41 -

Kendall and Pinecrest Historical Antecedents of Two Communities

77 Kendall and Pinecrest Historical Antecedents of Two Communities Scott F. Kenward, DMD Kendall and Pinecrest, south Miami-Dade County, encompass nearly 24 square miles and are home to more than 91,000 people. Their stories began in the area surrounding present-day Dixie Highway, from SW 90 Street south to SW 108 Street. Henry Kendall In 1884, Sir Edward Reed’s Florida Land and Mortgage Company appointed Henry John Broughton Kendall as one of four trustees to manage the company properties in Dade County. The son of the British Consul for Peru, Henry was born in Lima in 1841, returning as an infant with his family to their home in London the following year. The first three decades of Kendall’s life remain unknown, but we do know that by age 30 he was a foreign merchant and by age 38 had followed in his father’s footsteps, serving as the London Consul for Bolivia. By the time he travelled to America in 1883, Kendall had risen to the rank of Director of the Union Bank of London, a title he would hold at four additional major British firms over the next two decades. As a trustee of the Railway Investment Company and the Farmers’ Loan and Trust Company, which would eventually become Citibank, Kendall helped secure over 10 million dollars in loans for the construction of a tunnel under the Hudson River for steam trains, connecting New Jersey and New York City. Although a financial crisis ended the flow of invest ment capital from England, killing the project, the work would eventu ally resume in the 1920s, resulting in today’s Holland Tunnel. -

To Select South Floridals Top Law Firms, We Asked

Top law firms METHODOLOGY: TO SELECT SOUTH FLORIDA’s Top LAW FIRMS, WE ASKED THOUSANDS OF LAWYERS TO SUBMIT THEIR NOMINATIONS. AFTER CAREFULLY REVIEWING THOSE RESPONSES, WE PREPARED A FINAL LIST OF APPROXIMATELY 150 FIRMS, ALL WITH EXCELLENT CREDENTIALS. TOP law firms BARZEE FLORES BILZIN SUMBERG BAENA PRICE & [ A ] 169 E. Flagler St., Suite 1200 AXELROD LLP Miami, FL 33131 200 S. Biscayne Blvd., Suite 2500 ACKERMAN LINK & SARTORY, P.A. 305-374-3998 Miami, FL 33131 222 Lakeview Ave., Suite 1250 305-374-7580 West Palm Beach, FL 33401 BAST & AMRON LLP www.Bilzin.com 561-838-4100 1 SE 3rd Ave., Suite 1440 www.alslaw.com Miami, FL 33131 BIONDO LAW FIRM 305-379-7904 44 West Flagler St. Suite 2175 AKERMAN SENTERFITT www.bastamron.com Miami, FL 33130 1 SE 3rd Ave., 25th Floor 305-371-7326 Miami, FL 33131 BEASLEY HAUSER KRAMER LEONARD & www.biondolaw.com 305-374-5600 GALARDI, P.A. 350 E. Las Olas Blvd., Suite 1600 505 S. Flagler Dr., Suite 1500 BLACK, SREBNICK, KORNSPAN & Fort Lauderdale, FL 33301 West Palm Beach, FL 33401 STUMPF P.A. 954-463-2700 561-835-0900 201 S. Biscayne Blvd., Suite 1300 222 Lakeview Ave, Suite 400 www.beasleylaw.net Miami, FL 33131 West Palm Beach, FL 33401 305-371-6421 561-653-5000 BECKER & POLIAKOFF, P.A. www.RoyBlack.com www.akerman.com 3111 Stirling Road Fort Lauderdale, FL 33312 BLUESTEIN AND WAYNE, P.A. ALAN E. WEINSTEIN, LLC 954-987-7550 4000 Ponce de Leon Blvd., Suite 770 LAW OFFICES OF 121 Alhambra Plaza, 10th Floor Coral Gables, FL 33146 4500 Biscayne Blvd., Suite 203 Coral Gables, FL 33134 305-859-9200 Miami, FL 33137 305-262-4433 www.bw-pa.com 305-576-8666 625 N. -

Cultural and Spatial Perceptions of Miami‟S Little Havana

CULTURAL AND SPATIAL PERCEPTIONS OF MIAMI‟S LITTLE HAVANA by Hilton Cordoba A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Charles E. Schmidt College of Science in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida August 2011 Copyright by Hilton Cordoba 2011 ii CULTURAL AND SPATIAL PERCEPTIONS OF MIAMI'S LITTLE HAVANA by Hilton Cordoba This thesis was prepared under the direction ofthe candidate's thesis advisor, Dr. Russell Ivy, Department ofGeosciences, and has been approved by the members ofhis supervisory committee. It was submitted to the faculty ofthe Charles E. Schmidt College ofScience and was accepted in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Master ofArts. SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: ~s~~.Q~ a;;;::;.~. - Maria Fadiman, Pli.D. a~~ Es~ f2~_--- Charles Roberts, Ph.D. _ Chair, Department ofGeosciences ~ 8. ~- ..f., r;..r...-ry aary:pelT)(kll:Ii.- Dean, The Charles E. Schmidt College ofScience B~7Rlso?p~.D~~~ Date . Dean, Graduate College iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my gratitude to Dr. Russell Ivy for his support, encouragement, and guidance throughout my first two years of graduate work at Florida Atlantic University. I am grateful for the time and interest he invested in me in the midst of all his activities as the chair of the Geosciences Department. I am also thankful for having the opportunity to work with the other members of my advisory committee: Dr. Maria Fadiman and Dr. Charles Roberts. Thank you Dr. Fadiman for your input in making the survey as friendly and as easy to read as possible, and for showing me the importance of qualitative data. -

Riverview Historic District

RIVERVIEW HISTORIC DISTRICT SOUTHWEST MIAMI Designation Report – Amended 1 REPORT OF THE CITY OF MIAMI PRESERVATION OFFICER, MEGAN SCHMITT TO THE HISTORIC AND ENVIRONMENTAL PRESERVATION BOARD ON THE FINAL DESIGNATION OF THE RIVERVIEW HISTORIC DISTRICT Written by Marina Novaes, Historic Preservation Planner II Date: April 2015 Amended in May 5, 2015 2 Location and site maps 3 Contents I. General Information II. Statement Of Significance III. Description IV. Application of Criteria V. Bibliography VI. Photographs VII. Building Inventory List 4 I- General Information Historic Name: Riverview Subdivision Current Name: N/A Cultural Period of Significance: 1920s – 1960s Architectural Period of Significance: 1920 - 1950 Location: East Little Havana Present Owner: Multiple owners Present use: Residential / Commercial Zoning: T4-R Folio No.: 01-4138-003-4140; 01-4138-003-4160; 01-4138-003-1320; 01-4138-003-1330; 01-4138-125-0001; 01-4138-003-3920; 01-4138-003-4200; 01-4138-003-4180; 01-4138-003-3940; 01-4138-003-1390; 01-4138-003-1340; 01-4138-003-1400; 01-4138-101-0001; 01-4138-003-1420; 01-4138-003-1430; 01-4138-003-1440; 01-4138-003-1450; 01-4138-003-1371; 01-4138-003-1470; 01-4102-005-3750; 01-4102-005-3760; 01-4102-005-3770; 01-4138-003-2620; 01-4138-003-3970; 01-4138-003-1570; 01-4138-003-1580; 01-4138-003-1590; 01-4138-003-1540; 01-4138-003-1600; 01-4138-003-1530; 01-4138-003-1610; 01-4138-003-1520; 01-4138-003-1620; 01-4138-003-1510; 01-4138-026-0001; 01-4138-003-1500; 01-4138-003-1490; 01-4138-003-1480; 01-4138-003-1650; 01-4102-002-0550; -

Downtown Government Center Master Plan, May 1976

METROPOLITAN DADE COUNTY Stephen P. Clark Mayor Neal F. Adams County Commissioner Harry P. Cain County Commissioner Sidney Levin County Commissioner Clara Oesterle County Commissioner Beverly Phillips County Commissioner James F. Redford County Commissioner Sandy Rubenstein County Commissioner Harvey Ruvin County Commissioner R. Ray Goode County Manager May 17, 1976 Mr. A I f 0. Barth Chief Architect Metropolitan Dade County 140 West Flagler Street Miami, Florida 33130 Dear Mr. Barth: We take pleasure in submitting this Master Plan for Dade County's Downtown Government Center. The Master Plan has been prepared for us by Connel I Metcalf & Eddy and is submitted in accordance with our contract. This report is the last of three Milestone Reports and presents the DGC Program, its physical Design Plan, an Implementation Process and the Monual of Planning and Design Criteria. It is the blueprint for the next 25 years of development for this essential project which is already under construction. As part of our contract, a model of the DGC Design Plan has been bui It. We urge everyone who has not yet seen it, to make a point of doing so, for the mode I best i I I ustrates the essent i a I concepts of the Design Plan. Several actions by Dade County are recommended to bring the DGC Design Plan into being. These actions are presented in Section 6.0 dealing with the Implementation Process. This assignment could not have been completed without the cooperation and assistance of many County, City and other pub I ic officials who have provided ~alued guidance. -

2019 Greater Downtown Miami Annual Residential Market Study

Greater Downtown Miami Mid-YearAnnual ResidentialResidential Market Market Study Study Update AprilAugust 2019 2018 Prepared for the Miami Downtown Development Authority (DDA) By Integra Realty Resources (IRR) Greater Downtown Miami Annual Residential Market Study Prepared for the Miami Downtown Development Authority (DDA) by Integra Realty Resources (IRR) April 2019 For more information, please contact IRR-Miami/Palm Beach The Dadeland Centre 9155 S Dadeland Blvd, Suite 1208 Miami, FL 33156 305-670-0001 [email protected] Contents 2 Introduction 4 Greater Downtown Miami Condo Pipeline 6 Greater Downtown Miami Market Sizing 7 Greater Downtown Miami Market Condo Delivery and Absorption of Units 12 Analysis of Resale 13 2013-2018 Resale Inventory Retrospective 16 Currency Exchange and Purchasing Patterns 17 Current Cycle Completions 18 Major Market Comparison 19 Condominium Rental Activity 23 Conventional Rental Market Supply 27 Land Prices Trends 29 Opportunity Zone Analysis 30 Greater Downtown Miami Market Submarket Map 31 Conclusions 32 Condo Development Process Appendix Introduction Integra Realty Resources – Miami|Palm Beach (IRR-Miami) is pleased to present the following Residential Real Estate Market Study within the Miami Downtown Development Authority’s (Miami DDA) market area, defined as the Greater Downtown Miami market. This report updates IRR-Miami’s findings on the local residential real estate market through January 2019. Key findings are as follows: • The under construction pipeline delivered between Q2-Q4 2018 reduced the number of units under construction by 43% with a total of 1,649 units delivered, 1,020 of which were located in the Edgewater submarket, and 513 units representing the Canvas project in A&E.