Polieno BIANCO.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Battlefield Role of the Classical Greek General

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses The battlefield role of the Classical Greek general. Barley, N. D How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Barley, N. D (2012) The battlefield role of the Classical Greek general.. thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa43080 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ Swansea University Prifysgol Abertawe The Battlefield Role of the Classical Greek General N. D. Barley Ph.D. Submitted to the Department of History and Classics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2012 ProQuest Number: 10821472 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Alexander and the 'Defeat' of the Sogdianian Revolt

Alexander the Great and the “Defeat” of the Sogdianian Revolt* Salvatore Vacante “A victory is twice itself when the achiever brings home full numbers” (W. Shakespeare, Much Ado About Nothing, Act I, Scene I) (i) At the beginning of 329,1 the flight of the satrap Bessus towards the northeastern borders of the former Persian Empire gave Alexander the Great the timely opportunity for the invasion of Sogdiana.2 This ancient region was located between the Oxus (present Amu-Darya) and Iaxartes (Syr-Darya) Rivers, where we now find the modern Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, bordering on the South with ancient Bactria (present Afghanistan). According to literary sources, the Macedonians rapidly occupied this large area with its “capital” Maracanda3 and also built, along the Iaxartes, the famous Alexandria Eschate, “the Farthermost.”4 However, during the same year, the Sogdianian nobles Spitamenes and Catanes5 were able to create a coalition of Sogdianians, Bactrians and Scythians, who created serious problems for Macedonian power in the region, forcing Alexander to return for the winter of 329/8 to the largest city of Bactria, Zariaspa-Bactra.6 The chiefs of the revolt were those who had *An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Conflict Archaeology Postgraduate Conference organized by the Centre for Battlefield Archaeology of the University of Glasgow on October 7th – 9th 2011. 1 Except where differently indicated, all the dates are BCE. 2 Arr. 3.28.10-29.6. 3 Arr. 3.30.6; Curt. 7.6.10: modern Samarkand. According to Curtius, the city was surrounded by long walls (70 stades, i.e. -

Lucan's Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulf

Lucan’s Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: Catherine Connors, Chair Alain Gowing Stephen Hinds Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Classics © Copyright 2014 Laura Zientek University of Washington Abstract Lucan’s Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Catherine Connors Department of Classics This dissertation is an analysis of the role of landscape and the natural world in Lucan’s Bellum Civile. I investigate digressions and excurses on mountains, rivers, and certain myths associated aetiologically with the land, and demonstrate how Stoic physics and cosmology – in particular the concepts of cosmic (dis)order, collapse, and conflagration – play a role in the way Lucan writes about the landscape in the context of a civil war poem. Building on previous analyses of the Bellum Civile that provide background on its literary context (Ahl, 1976), on Lucan’s poetic technique (Masters, 1992), and on landscape in Roman literature (Spencer, 2010), I approach Lucan’s depiction of the natural world by focusing on the mutual effect of humanity and landscape on each other. Thus, hardships posed by the land against characters like Caesar and Cato, gloomy and threatening atmospheres, and dangerous or unusual weather phenomena all have places in my study. I also explore how Lucan’s landscapes engage with the tropes of the locus amoenus or horridus (Schiesaro, 2006) and elements of the sublime (Day, 2013). -

Eumenes, Neoptolemus and "PSI" XII 1284 Bosworth, a B Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Jan 1, 1978; 19, 3; Periodicals Archive Online Pg

Eumenes, Neoptolemus and "PSI" XII 1284 Bosworth, A B Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Jan 1, 1978; 19, 3; Periodicals Archive Online pg. 227 Eumenes, Neoptolemus and PSI XII 1284 A. B. Bosworth N 1932 E. Breccia discovered a small scrap of papyrus at Kom Ali I el Gamman near Oxyrhynchus. Once discovered it waited nearly twenty years for publication. The editio princeps of 1951 was the work of Vittorio Bartoletti, aided by suggestions from Maas and Jacoby.1 The papyrus itself consists of three columns, numbered consecutively 81-83, of which the central column is preserved almost complete. Those to right and left are defective except for a few letters at the extremities which defy reconstruction.2 The script belongs to the late second century. I shall first give the text with rudimentary critical apparatus and then a translation of the consecutive narrative. ]!,TE"e [we cp]9flfPwTarrjV 7ToL[~e]ff!' r9~e i7T7T[E"v]eLv [T]~V 0tPW €7TEXcfJpoVV [€]v TagE [£] oi S€ KaT67TLv av.rwv, oeo£ imrije, fJ T [V]XOL ~g!}'59!,TL~OV wc lmO rfj gVVEXE{~ [T]WV fl~~cP!, cWa~:rEAoVvTE[C] ~v EP./-'O/\!}!,, a \, TWVA" L7T7TEWV. E"VP.EV1JC OE,"" wc( 'T7}VI TE SV'}'K/\T/CLVI:. I \ TOV- svvac-I:. 5 7TLCp.oV 7C!W Ma'5~S6vwV7TVK~V KaTELSEV Kat aVTOVC T~j~ yvcfJp.a[LC] EC, TO"'".... E7TL 7Tav KLVOVVEVELV~ " EPPWP.EVOVC,, 7TEP.7TELI av1"'0 LC .!:t,EVVLav~ I avopaJI ~ p.aKE"Sovt~ov7a rfj <p [W ]vfl, <ppacaL KEAEvcac WC KaTU c76p.a P.€V ou p.aXEL7aL aUToLc 7Tapa'5[oAov]~wv S~ T[fi] TE i7T7TC[) Kat TaLC TWV tPLAwv 7agECLV E"t[p]gOL aUTovc TWV E7TL7[rySEl]wv' oi S€, El Kat [EL] 10 7Tapv IXp.axol TLVEC ccptc [L]!, St;JKOVCLV aM' OtJT' [«Xv] Tep ')IE ALP.ep EVt V9~[V] avTLT[ 1 vO/Ll'O]r'TEC Latte: perhaps E1TtVOOV]r'TEC (cf Arrian 1.23.5 [see below]). -

Companion Cavalry and the Macedonian Heavy Infantry

THE ARMY OP ALEXANDER THE GREAT %/ ROBERT LOCK IT'-'-i""*'?.} Submitted to satisfy the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. in the School of History in the University of Leeds. Supervisor: Professor E. Badian Date of Submission: Thursday 14 March 1974 IMAGING SERVICES NORTH X 5 Boston Spa, Wetherby </l *xj 1 West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ. * $ www.bl.uk BEST COPY AVAILABLE. TEXT IN ORIGINAL IS CLOSE TO THE EDGE OF THE PAGE ABSTRACT The army with which Alexander the Great conquered the Persian empire was "built around the Macedonian Companion cavalry and the Macedonian heavy infantry. The Macedonian nobility were traditionally fine horsemen, hut the infantry was poorly armed and badly organised until the reign of Alexander II in 369/8 B.C. This king formed a small royal standing army; it consisted of a cavalry force of Macedonian nobles, which he named the 'hetairoi' (or Companion]! cavalry, and an infantry body drawn from the commoners and trained to fight in phalangite formation: these he called the »pezetairoi» (or foot-companions). Philip II (359-336 B.C.) expanded the kingdom and greatly increased the manpower resources for war. Towards the end of his reign he started preparations for the invasion of the Persian empire and levied many more Macedonians than had hitherto been involved in the king's wars. In order to attach these men more closely to himself he extended the meaning of the terms »hetairol» and 'pezetairoi to refer to the whole bodies of Macedonian cavalry and heavy infantry which served under him on his campaigning. -

Joseph Scaliger, Isaac Casaubon and Richard Thomson Paul Botley University of Warwick

Three Very Different Translators: Joseph Scaliger, Isaac Casaubon and Richard Thomson Paul Botley University of Warwick This essay revisits some ideas on translation which I developed several years ago. They 477 were published as part of a book on Latin translation in the fifteenth and early six- teenth centuries, and one of the purposes of the present essay is to discover whether the intervening years have been kind to them. That book,Latin Translation in the Renaissance, examined the work of a number of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century translators, in particular, Leonardo Bruni, Giannozzo Manetti and Desiderius Erasmus, and suggested an alternative approach to categorising renaissance translations. It argued that in the fifteenth century ideas about translation became more sophisticated because of the proliferation of different translations of the same text. This was a new phenomenon: by and large, the Middle Ages had been obliged to make do with unique versions of a rather small number of Greek texts, and medieval scholars were seldom in a position to compare the merits of rival versions. In the fifteenth century, a number of versions of the same Greek text became available. As a consequence of this multiplication of renderings, even those who knew nothing of the original language were able to evaluate the differences between versions. Thus, in the fifteenth century, it became possible for a reader with no knowledge of Greek to deepen his understanding of a Greek author by collating a number of Latin translations of the original text. In such circumstances, the relation- ship of the translation to the other available translations was at least as important as the relationship of the translation to the original, Greek, text.1 Thinking about these relationships between these early modern translations led me to suggest that they could be placed into three broad categories, which I called replacements, competitors and supplements. -

The Statues of Horatius Cocles and Cloelia By

Legendary Art & Memory in Republican and Imperial Rome: the Statues of Horatius Cocles and Cloelia By Copyright 2014 Andrea Samz-Pustol Submitted to the graduate degree program in Classics and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Phil Stinson ________________________________ John Younger ________________________________ Tara Welch Date Defended: June 7, 2014 The Thesis Committee for Andrea Samz-Pustol certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Legendary Art & Memory in Republican and Imperial Rome: the Statues of Horatius Cocles and Cloelia ________________________________ Chairperson Phil Stinson Date approved: June 8, 2014 ii Abstract The display contexts of the bronze statues of legendary heroes, Horatius Cocles and Cloelia, in the Roman Forum influenced the representation of these heroes in ancient texts. Their statues and stories were referenced by nearly thirty authors, from the second century BCE to the early fifth century CE. Previous scholarship has focused on the bravery and exemplarity of these heroes, yet a thorough examination of their monuments and their influence has never been conducted.1 This study offers a fresh outlook on the role the statues played in the memory of ancient authors. Horatius Cocles and Cloelia are paired in several ancient texts, but the reason for the pairing is unclear in the texts. This pairing is particularly unique because it neglects Mucius Scaevola, whose deeds were often relayed in conjunction with Horatius Cocles’ and Cloelia’s; all three fought the same enemy at the same time and place. This pairing can be attributed, however, to the authors’ memory of the statues of the two heroes in the Forum. -

What Were Philip II's Reforms of the Macedonian Military and How

The Military Revolution: What were Philip II’s Reforms of the Macedonian Military and how Revolutionary were they? Classics Dissertation B070075 MA (Hons) Classical Studies The University of Edinburgh B070075 Acknowledgements My thanks to Dr Christian Djurslev for his supervision and assistance with this Dissertation. 1 B070075 Table of Contents List of illustrations…………………………………………………………....... 3 Introduction……………………………….……………………………………..4 Chapter One – The Reforms…………………………………………………… 8 Chapter Two – Effectiveness…………………………………………………. 26 Chapter Three – Innovation………………………………………………..…. 38 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………. 48 Bibliography………………………………………………………….............. 51 Word Count: 13,998 B070075 2 B070075 List of Illustrations Fig. 1. Three of the iron spearheads from ‘Philip’s Tomb’at Vergina. (Source: Andronicos, M. (1984), Vergina: The Royal Tombs and the Ancient City, Athens, p144.) Fig. 2. Reconstruction drawing of a fresco, now destroyed. Mounted Macedonian attacking Persian foot soldier. From Tomb of Naoussa (Kinch’s Tomb) dated to 4th C BC. (Source: http://library.artstor.org.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/#/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822000408458 )(accessed 03/03/2018). Fig. 3. Stylized image of what a typical hoplite phalanx looked like. (Source: ‘The Hoplite Battle Experience: The Nature of Greek Warfare and a Western Style of Fighting’ , http://sites.psu.edu/thehopliteexperience/the-phalanx/ ) (Accessed 03/03/18) Fig. 4. A Macedonian phalanx in formation. Illustration by Erin Babnik. (Source: https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo-a-macedonian-phalanx-in-formation-illustration-by- erin-babnik-33292918.html ) (Accessed 03/04/18) Fig. 5. The Battle of Chaeronea, 338BC. (Source: Hammond, N. G. L. (1989), The Macedonian State: The Origins, Institutions, and History, Oxford, p117.) Fig. 6. The Battles of Leuctra and against Bardylis. (Source: Hammond, N. -

Synesius of Cyrene's Calvitii Encomium, Arrian's Anabasis

Karanos 1, 2018 55-65 Battling without Beards: Synesius of Cyrene’s Calvitii encomium, Arrian’s Anabasis Alexandri and the Alexander discourse of the fourth century AD.* by Christian Thrue Djurslev Aarhus University [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper explores the literary tradition of the curious chreia that Alexander ordered his men to shave off their beards before battle. The story is represented by various sources from the imperial period but most prominently in the Encomium of Baldness by Synesius of Cyrene. The latter source posits that the story comes from the History of Alexander by Ptolemy, son of Lagus, but this claim cannot be true when Synesius’ version is compared to other extant uses of the chreia. This paper exemplifies some of Synesius’ methods of working, arguing that we need to invest more energy in appreciating the wider tradition of Alexander in late antiquity to understand our earlier texts. KEYWORDS Alexander; Ptolemy I; Arrian; Synesius of Cyrene; Dio Chrysostom; Julius Africanus; chreia; literary tradition; Late Antiquity; early Christian literature. “It seems unavoidable that the reputation of Arrian and his Alexander history was undiminished in the fourth century.” BOSWORTH (1980, i, 38) When reflecting upon the grand career of Brian Bosworth, his historical commentary on Arrian’s Anabasis Alexandri is inescapable. Though still incomplete, he began the projected three-volume work more than a generation ago, and it will stand as an authoritative tool for all future scholars of Alexander. In the first volume, from which the epigraph is taken, he offers an extensive introduction to Arrian’s authorship. -

Pushing the Boundaries of Myth: Transformations of Ancient Border

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PUSHING THE BOUNDARIES OF MYTH: TRANSFORMATIONS OF ANCIENT BORDER WARS IN ARCHAIC AND CLASSICAL GREECE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CLASSICS: ANCIENT MEDITERRANEAN WORLD BY NATASHA BERSHADSKY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MARCH 2013 UMI Number: 3557392 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3557392 Published by ProQuest LLC (2013). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 Acknowledgements I would like to express my deep gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee, Jonathan Hall, Christopher Faraone, Gloria Ferrari Pinney and Laura Slatkin, whose ideas and advice guided me throughout this research. Jonathan Hall’s energy and support were crucial in spurring the project toward completion. My identity as a classicist was formed under the influence of Gregory Nagy. I would like to thank him for the inspiration and encouragement he has given me throughout the years. Daniela Helbig’s assistance was invaluable at the finishing stage of the dissertation. I also thank my dear colleague-friends Anna Bonifazi, David Elmer, Valeria Segueenkova, Olga Levaniouk and Alexander Nikolaev for illuminating discussions, and Mira Bernstein, Jonah Friedman and Rita Lenane for their help. -

Illinois Classical Studies

NOTICE: Return or renew a I Library MatoriatsI The Minimum Fm for each Lost Book is $50.00. The person charging this material is responsible for us return to the library from which it was withdrawn on or before the Latest Date stamped below ""* ""<'eriining of books are reasons for discipli- naryI-«";T**"*'*!r'action and may result in dismissal from the To ''""">^'^-University renew call Telephone Center, 333-8400 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN 1 ILLINOIS CLASSICAL STUDIES VOLUME XII. 1 Spring 1987 J. K. Newman, Editor Patet omnibus Veritas; nondum est occupata; multum ex ilia etiamfuturis relictum est. Sen. Epp. 33. 1 SCHOLARS PRESS ISSN 0363-1923 ILLINOIS CLASSICAL STUDIES VOLUME XII.l ©1987 The Board of Trustees University of Illinois Copies of the journal may be ordered from: Scholars Press Customer Services P. O. Box 6525 Ithaca, New York 14851 Printed in the U.S.A. ADVISORY EDITORIAL COMMITTEE John J. Bateman David F. Bright Howard Jacobson Miroslav Marcovich Responsible Editor: J. K. Newman The Editor welcomes contributions, which should not normally exceed twenty double-spaced type4 pages, on any topic relevant to the elucidation of classical antiquity, its transmission or influence. Consistent with the mamtenance of scholarly rigor, contributions are especially appropriate which deal with major questions of interpretation, or which are likely to interest a wider academic audience. Care should be taken in presentation to avoid technical jargon, and the trans-rational use of acronyms. Homines cum hominibus loquimur. Contributions should be addressed to: The Editor, Illinois Classical Studies, Deparunent of the Classics, 4072 Foreign Languages Building, 707 South Mathews Avenue, Urbana, Illinois 61801 Each contributor receives twenty-five offprints. -

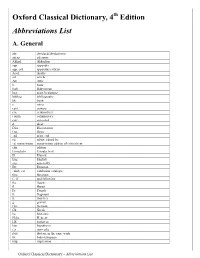

Abbreviations List A

Oxford Classical Dictionary, 4th Edition Abbreviations List A. General abr. abridged/abridgement adesp. adespota Akkad. Akkadian app. appendix app. crit. apparatus criticus Aeol. Aeolic art. article Att. Attic b. born Bab. Babylonian beg. at/nr. beginning bibliog. bibliography bk. book c. circa cent. century cm. centimetre/s comm. commentary corr. corrected d. died Diss. Dissertation Dor. Doric end at/nr. end ed. editor, edited by ed. maior/minor major/minor edition of critical text edn. edition Einzelschr. Einzelschrift El. Elamite Eng. English esp. especially Etr. Etruscan exhib. cat. exhibition catalogue fem. feminine f., ff. and following fig. figure fl. floruit Fr. French fr. fragment ft. foot/feet g. gram/s Ger. German Gk. Greek ha. hectare/s Hebr. Hebrew HS sesterces hyp. hypothesis i.a. inter alia ibid. ibidem, in the same work IE Indo-European imp. impression Oxford Classical Dictionary – Abbreviations List in. inch/es introd. introduction Ion. Ionic It. Italian kg. kilogram/s km. kilometre/s lb. pound/s l., ll. line, lines lit. literally lt. litre/s L. Linnaeus Lat. Latin m. metre/s masc. masculine mi. mile/s ml. millilitre/s mod. modern MS(S) manuscript(s) Mt. Mount n., nn. note, notes n.d. no date neut. neuter no. number ns new series NT New Testament OE Old English Ol. Olympiad ON Old Norse OP Old Persian orig. original (e.g. Ger./Fr. orig. [edn.]) OT Old Testament oz. ounce/s p.a. per annum PIE Proto-Indo-European pl. plate plur. plural pref. preface Proc. Proceedings prol. prologue ps.- pseudo- Pt. part ref. reference repr.