Privacy Risks from Public Data Sources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tax Identification Number Reference Guide

Tax Identification Number (TIN). Reference Guide. The following are examples of TINs from some of the countries where our customers may have foreign tax residency. China India TIN on Certificate of Tax Registration Permanent Account TIN on Business Licence Number (PAN) (Credibility Code) TIN on Identification Card United Kingdom New Zealand Unique Taxpayer Reference Inland Revenue Number (UTR) Department Number (IRD) National Insurance Number (NINO) Korea Brazil MINISTERIO´ DA FAZENDA Resident Registration Secretaria da Receita Federal Number (RRN) Cadastro CPFde Pessoas F’sicas Numero de Inscri ‹o Cadastro de Pessoas 000.000.000-00 JUAN FAZENDA Nome 12.345.888/8888-24 Fisicas (CPF) NOME DA PESSOA Nascimento 01/01/1990 Cadastro Nacional da Pessoa Juridica (CNPJ) Phillipines REPUBLI C OF TH E P HILIPPINE S Malaysia DEPARTMENT OF FINANCE BUREAU OF INTERNAL REVENUE TIN Tax Payer 456-888-888-00000 DIREKTORAT JENDERAL PAJAK CRUZ, BAYANI Identification Number 10 REYES COMPOUND KALAYAAN SUBDIVISION, MUNTINLUPA CITY Nombor Cukai NPWP : 27.938.653.5-024.00 0 BIRTHDA TE ISSUE DATE Pendapatan (NPWP) RAHMAN EK A PUTR A 03/08/1981 1/27/1999 JL.KELAP A DUA NO. 18 RT.006/00 6 KELAP A DUA - KEBON JERU K JAKA RTA BAR AT 911550 ) TGL TERDAFT AH 06-10-200 5 Tax Identification Number (TIN). Reference Guide. The following are examples of TINs from some of the countries where our customers may have foreign tax residency. Canada USA Social Insurance Number (SIN) Social Security Number Business Number (BN) Indonesia Pakistan KEMENTERIAN KEUANGAN REPUBLIK INDONESIA DIREKTORAT JENDERAL PAJAK KEMENTERIAN KEUANGAN REPUBLIK INDONESIA National Tax NPWP : 31.806.502.6-422.000DIREKTORAT JENDERAL PAJAK NPWP : 31.806.502.6-422.000 Number (NTN) NAMA NAM: AMAHY: MAHYADI PANGGABEAN PANGGABEAN Nomor Pokok Wajib NIK : - NIK ALAM: AT- : JL.TERUSAN PASIRKOJA BELAKANG NO.130 RT 006 RW 001 Pajak (NPWP) JAMIKA-BOJONG LOA KALER BANDUNG ALAMAT KPP: JL.TERUSAN: 422 PASIRKOJA BELAKANG NO.130 RT 006 RW 001 JAMIKA-BOJONG LOA KALER BANDUNG KPP : 422 Singapore South Africa REPUBLIC OF SINGAPO RE IDENTITY CARD NO . -

Payroll Operations in the Americas

Payroll Operations in the Americas — essential compliance and reporting considerations Introduction This booklet contains market-by- on newly established, standalone market guidance on the key HR operations. Where the Americas payroll and immigration matters to operation is a regional headquarters be considered as you expand your or a holding company for foreign operations across Americas, current subsidiaries, or if there are existing as of March 2019. operations in Americas, other In our experience, careful considerations must be taken into consideration of these matters at the account. outset is the most effective way of In all situations, we recommend that avoiding any issues and ensuring an you seek specific professional advice optimal set-up structure of your from the contacts listed in each business and employees in new chapter. They will take into Americas markets. consideration your specific This booklet is general in nature and circumstances and objectives. not to be relied on as professional advice. Further, the chapters focus Contents Introduction .............................................2 Ecuador .................................................20 EY contact ................................................3 El Salvador .............................................24 Argentina .................................................4 Guatemala ..............................................26 Brazil .......................................................6 Mexico ...................................................28 Canada.....................................................8 -

The Social Security Number: Legal Developments Affecting Its Collection, Disclosure, and Confidentiality

Order Code RL30318 The Social Security Number: Legal Developments Affecting Its Collection, Disclosure, and Confidentiality Updated February 21, 2008 Kathleen S. Swendiman Legislative Attorney American Law Division The Social Security Number: Legal Developments Affecting Its Collection, Disclosure, and Confidentiality Summary While the social security number (SSN) was first introduced as a device for keeping track of contributions to the Social Security system, its use has been expanded by government entities and the private sector to keep track of many other government and private sector records. Use of the social security number as a federal government identifier was based on Executive Order 9393, issued by President Franklin Roosevelt. Beginning in the 1960s, federal agencies started adopting the social security number as a governmental identifier, and its use for keeping track of government records, on both the federal and state levels, greatly increased. Section 7 of the Privacy Act of 1974 limits compulsory divulgence of the social security number by government entities. While the Privacy Act does provide some limits on the use of the social security number by state and federal entities, exceptions provided in that statute and succeeding statutes have resulted in only minimal restrictions on governmental usage of the social security number. Constitutional challenges to social security number collection and dissemination have, for the most part, been unsuccessful. Private sector use of the social security number is widespread and continues to be largely unregulated by the federal government. The chronology in this report provides a list of federal developments affecting use of the social security number, including federal regulation of the number, as well as specific authorizations, restrictions, and fraud provisions concerning its use. -

Electronic Identification (E-ID)

EXPLAINING INTERNATIONAL IT APPLICATION LEADERSHIP: Electronic Identification Daniel Castro | September 2011 Explaining International Leadership: Electronic Identification Systems BY DANIEL CASTRO SEPTEMBER 2011 ITIF ALSO EXTENDS A SPECIAL THANKS TO THE SLOAN FOUNDATION FOR ITS GENEROUS SUPPORT FOR THIS SERIES. SEPTEMBER 2011 THE INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY & INNOVATION FOUNDATION | SEPTEMBER 2011 PAGE II TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ V Introduction..................................................................................................................... 1 Background ....................................................................................................................... 1 Box 1: Electronic Passports ............................................................................................. 3 Terminology and Technology ........................................................................................... 3 Electronic Signatures, Digital Signatures and Digital Certificates ............................... 3 Identification, Authentication and Signing ................................................................ 4 Benefits of e-ID Systems ............................................................................................ 5 Electronic Identification Systems: Deployment and Use .............................................. 6 Country Profiles ............................................................................................................. -

SOCIAL SECURITY NUMBERS 13 Nov 01 MTL 13/05 Part a TANF TANF TANF TANF TANF TANF SNAP SNAP SNAP SNAP SNAP SNAP

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1310 Eligibility Requirement 1311 Worker Actions at Application 1312 Action at TANF Redetermination/SNAP Recertifications 1320 Failure to Comply 1321 Reestablishing Eligibility 1 Division of Welfare and Supportive Services 1300 Eligibility and Payments Manual SOCIAL SECURITY NUMBERS 13 Nov 01 MTL 13/05 Part A TANF TANF TANF TANF TANF TANF SNAP SNAP SNAP SNAP SNAP SNAP Social Security Numbers 1310 ELIGIBILITY REQUIREMENT As a condition of eligibility each applicant for or recipient of aid is required to furnish a Social Security account number (SSN) prior to approval, unless religious beliefs prohibit enumeration. Applicants and recipients of aid include individuals seeking or receiving assistance and any other individuals whose needs/income are considered in determining the amount of assistance. Once proof of application has been provided, do not deny, delay or discontinue benefits pending receipt of the SSN. Exceptions: ● Good cause — Individuals who cannot provide the verifications required by Social Security to apply for an SSN may receive assistance for each month they have good cause. Good cause exists when circumstances beyond the household’s control prevent them from securing proof required to obtain an SSN. The household must report what actions have been taken to obtain the required verifications to apply for an SSN at redetermination/recertification. The SSN application must be completed as soon as verifications are received. Expedited service – Applicants eligible for expedited service may participate the first month without providing or applying for an SSN. Excluded Persons: Non-qualified non-citizens are not required to provide or apply for an SSN. If the non- qualified non-citizen’s income and resources are countable to the individuals seeking or receiving benefits, other methods of income verification must be pursued. -

How to Apply for a Social Insurance Number in Some EU States

Professional European and Worldwide Accounts and Tax Advisors How to Apply for a Social Insurance Number in Some EU States This document provides information on obtaining a Social Insurance number in the following EU member states: Ø Spain Ø Belgium Ø Germany Ø Italy Ø Sweden Ø Poland Ø Norway Ø Denmark Ø Portugal Ø Greece Ø Hungary Ø Lithuania Ø Malta Ø The Netherlands Spain To apply for a Social Insurance number in Spain you first need to apply for a NIE number. How to get an NIE number in Spain The application process is quite easy. Go to your local National Police Station, to the Departmento de Extranjeros (Foreigners Department) and ask for the NIE application form. The following documents must be submitted to the police station to obtain a NIE number: Ø Completed and signed original application and a photocopy (original returned) Form can be downloaded here: http://www.mir.es/SGACAVT/extranje/regimen_general/identificacion/nie.htm Ø Passport and photocopy Address in Spain (you can use a friend's) Ø Written justification of why you need the NIE (issued by an accountant, a notary, a bank manager, an insurance agent a future employer, etc.) If you have any questions, call the National Police Station, the Departamento de Extranjeros (Foreigners Department) Tel: (+34) 952 923 058 When you hand in the documentation, a stamped photocopy of the application is returned to you along with your passport. Ask them when you should come back to pick up the document. The turnaround time fluctuates and your NIE can take one to six weeks. -

Criminal Background Check Procedures

Shaping the future of international education New Edition Criminal Background Check Procedures CIS in collaboration with other agencies has formed an International Task Force on Child Protection chaired by CIS Executive Director, Jane Larsson, in order to apply our collective resources, expertise, and partnerships to help international school communities address child protection challenges. Member Organisations of the Task Force: • Council of International Schools • Council of British International Schools • Academy of International School Heads • U.S. Department of State, Office of Overseas Schools • Association for the Advancement of International Education • International Schools Services • ECIS CIS is the leader in requiring police background check documentation for Educator and Leadership Candidates as part of the overall effort to ensure effective screening. Please obtain a current police background check from your current country of employment/residence as well as appropriate documentation from any previous country/countries in which you have worked. It is ultimately a school’s responsibility to ensure that they have appropriate police background documentation for their Educators and CIS is committed to supporting them in this endeavour. It is important to demonstrate a willingness and effort to meet the requirement and obtain all of the paperwork that is realistically possible. This document is the result of extensive research into governmental, law enforcement and embassy websites. We have tried to ensure where possible that the information has been obtained from official channels and to provide links to these sources. CIS requests your help in maintaining an accurate and useful resource; if you find any information to be incorrect or out of date, please contact us at: [email protected]. -

Application for the Social Security Card

Form SS-5-FS (11-2019) UF Discontinue Prior Editions Page 1 of 5 SOCIAL SECURITY ADMINISTRATION OMB No. 0960-0066 Application for a Social Security Card Applying for a Social Security Card is free! USE THIS APPLICATION TO: • Apply for an original Social Security card • Apply for a replacement Social Security card • Change or correct information on your Social Security number record IMPORTANT: You MUST provide a properly completed application and the required evidence before we can process your application. We can only accept original documents or documents certified by the custodian of the original record. Notarized copies or photocopies which have not been certified by the custodian of the record are not acceptable. We will return any documents submitted with your application. For assistance, contact any U.S. Social Security office or your Federal Benefits Unit. For a complete list of Federal Benefits Units and contact information, visit www.socialsecurity.gov/foreign. Original Social Security Card To apply for an original card, you must provide at least two documents to prove age, identity, and U.S. citizenship or current lawful, work-authorized immigration status. If you are not a U.S. citizen and do not have Department of Homeland Security (DHS) work authorization, you must prove that you have a valid non-work reason for requesting a card. See page 2 for an explanation of acceptable documents. NOTE: If you are age 12 or older and have never received a Social Security number, you must apply in person. Replacement Social Security Card To apply for a replacement card, you must provide one document to prove your identity. -

Identity Theft and Your Social Security Number

Identity Theft and Your Social Security Number SSA.gov Identity theft is one of the fastest growing crimes in America. A dishonest person who has your Social Security number can use it to get other personal information about you. Identity thieves can use your number and your good credit to apply for more credit in your name. Then, when they use the credit cards and don’t pay the bills, it damages your credit. You may not find out that someone is using your number until you’re turned down for credit, or you begin to get calls from unknown creditors demanding payment for items you never bought. Someone illegally using your Social Security number and assuming your identity can cause a lot of problems. Your number is confidential The Social Security Administration protects your Social Security number and keeps your records confidential. We don’t give your number to anyone, except when authorized by law. You should be careful about sharing your number, even when you’re asked for it. You should ask why your number is needed, how it’ll be used, and what will happen if you refuse. The answers to these questions can help you decide if you want to give out your Social Security number. 1 How might someone steal your number? Identity thieves get your personal information by: • Stealing wallets, purses, and your mail (bank and credit card statements, pre-approved credit offers, new checks, and tax information). • Stealing personal information you provide to an unsecured site online, from business or personnel records at work, and personal information in your home. -

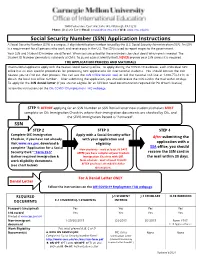

Social Security Number (SSN) Application Instructions a Social Security Number (SSN) Is a Unique, 9-Digit Identification Number Issued by the U.S

5000 Forbes Ave, Cyert Hall Suite 101, Pittsburgh, PA 15213 Phone: (412) 268-5231 ▪ Email: [email protected] ▪ Web: www.cmu.edu/oie Social Security Number (SSN) Application Instructions A Social Security Number (SSN) is a unique, 9-digit identification number issued by the U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA). An SSN is a requirement for all persons who work and receive pay in the U.S. The SSN is used to report wages to the government. Your SSN and Student ID number are different. When you are asked for these numbers, be clear about which one is needed. The Student ID Number generally is valid only at CMU. To guard against identity theft, NEVER provide your SSN unless it is required. THE APPLICATION PROCESS AND MATERIALS International applicants apply with the nearest Social Security office. To apply during the COVID-19 outbreak, each individual SSN office has its own specific procedures for processing SSN applications for international students. You should contact the SSA nearest you to find out their process. You can use the SSN Office locator tool, or call the national SSA line at 1-800-772-1213 to obtain the local SSA office number. After submitting the application, you should receive the SSN card in the mail within 30 days. To apply for the SSN denial letter (if you are not eligible for an SSN but need documentation required for PA driver’s license) Follow the instructions on the OIE COVID-19 Employment FAQ webpage. STEP 1: BEFORE applying for an SSN Number or SSN Denial Letter new students/scholars MUST complete an OIE Immigration Check-In, where their immigration documents are checked by OIE, and the SEVIS Immigration Record is “Activated”. -

TIN Description

Poland -Information on Tax Identification Numbers Section I – TIN Description I. TIN description 1.1. PESEL description As from 1st September 2011, Poland recognizes as a tax identification number the PESEL number issued to natural persons registered in PESEL register and who do not conduct business activity and are not registered for value added tax purposes. PESEL is a 11-digit, constant numeric symbol, that uniquely identifies a specific individual registered in the PESEL database (the Common Electronic System of Population Register). Data stored in the Common Electronic System of Population Register is transferred from the municipal offices’ database, which are the municipal registration records. PESEL register operates since 1979 and contains details of persons residing permanently in the territory of the Republic of Poland, domiciled for permanent or temporary (more than 3 months) residence and persons applying for an identity card or passport, as well as people who under the provisions of Polish law need to have a social security number. PESEL numbers are issued by the Ministry of Internal Affairs. 1.2. TIN description As from 1st of September 2011, Poland issues TINs to other entities, which are subject to registration (i.e. individuals, legal persons, individuals who do not have the legal personality and other entities) provided that, according to the Polish acts, they are defined as taxpayers or payers of social security or health insurance contributions. However, TIN number assigned to the date 31st August 2011 becomes a tax identification number under the provisions of Act of 29 July 2011 concerning the rules governing registration and identification (Official Journal No 171, item 1016), and thus decisions on granting such a tax identification number remain in force. -

Data Quality Accelerator Guide

Informatica® 10.2 HotFix 1 Data Quality Accelerator Guide Informatica Data Quality Accelerator Guide 10.2 HotFix 1 April 2019 © Copyright Informatica LLC 2009, 2019 This software and documentation are provided only under a separate license agreement containing restrictions on use and disclosure. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, by any means (electronic, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without prior consent of Informatica LLC. U.S. GOVERNMENT RIGHTS Programs, software, databases, and related documentation and technical data delivered to U.S. Government customers are "commercial computer software" or "commercial technical data" pursuant to the applicable Federal Acquisition Regulation and agency-specific supplemental regulations. As such, the use, duplication, disclosure, modification, and adaptation is subject to the restrictions and license terms set forth in the applicable Government contract, and, to the extent applicable by the terms of the Government contract, the additional rights set forth in FAR 52.227-19, Commercial Computer Software License. Informatica, PowerCenter, and the Informatica logo are trademarks or registered trademarks of Informatica LLC in the United States and many jurisdictions throughout the world. A current list of Informatica trademarks is available on the web at https://www.informatica.com/trademarks.html. Other company and product names may be trade names or trademarks of their respective owners. Portions of this software and/or documentation are subject to copyright held by third parties. Required third party notices are included with the product. The information in this documentation is subject to change without notice. If you find any problems in this documentation, report them to us at [email protected].