Papers Are Circulated in England Or Scottish Programme Material Is Shown in England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Legal System

ELEVENTH EDITION English Legal System ‘The book has several strengths welcome to students and lecturers alike: up to date, well-written and comprehensive. It provides clear exposition of the central themes whilst the delightful layout makes the information readily accessible.’ Dr. Jackson Maogoto, Senior Lecturer, University of Manchester English Legal System is the best-selling undergraduate text on this subject, providing an authoritative and engaging account of the structure and mechanisms of the law in England and Wales. The authors skilfully present a thought- provoking analysis of the subject, making this the defi nitive introduction to the area and the fi rst choice for students year after year. Annually revised and fully updated, Elliott and Quinn’s English Legal System continues to keep you fully informed of progress and changes premium within this constantly evolving topic. Some key recent developments covered in this eleventh edition include: • The establishment of the Supreme Court • Planned reforms in the Constitutional Reform and Governance Bill Do you want to give yourself a head start come • Changes to the regulation of the legal profession, including the exam time? establishment of the Legal Services Board Visit www.mylawchamber.co.uk/ElliottELS • The opening of family courts to the media to access the accompanying Pearson eText, an • Police tactics following the G20 demonstrations electronic version of English Legal System. The eText is fully linked to interactive quizzes, This eleventh edition offers: sample exam questions with answer guidance, • Comprehensive exposition of the legal system of England and Wales and fl ashcards – all designed so that you can test yourself on topics covered in this book. -

Express and Implied Limits on Judicial Review: Ouster and Time Limit Clauses, the Prerogative Power, Public Interest Immunity

17 Express and implied limits on judicial review: ouster and time limit clauses, the prerogative power, public interest immunity 17.1 Introduction We have already seen that the expansion of judicial review is one conspicuous feature of English administrative law over recent decades. This chapter will, fi rst, be concerned with examining how far is it possible to exclude the jurisdiction of the courts by the careful drafting of objectively worded statutory ouster pro- visions, and by the use of subjective language allowing considerable discretion to the decision-taker. In particular, secondly, we will focus on two areas where implied, rather than express, limits are central: the prerogative power, and the use of public interest immunity by government and other bodies. This is important because, if in advance of any action it is recognised that the exclusion of the courts has been achieved, this is a clear signal to decision-takers that they may operate without fear of intervention by the courts at a later stage. However, judges are aware of their constitutional position, and particularly of the doctrine of the rule of law. The result is that they have been unwilling to permit any subordinate authority to obtain uncontrollable power which would exempt public authorities, or other bodies, from the jurisdiction of the courts, as this would be, theoretically, tantamount to opening the door to potentially dictatorial power. For example, strong opposition was expressed in political, judicial and academic circles to a recent proposal by the government to insert an Ouster Clause in the Asylum and Immigration Bill 2004 which sought to exclude entirely the jurisdiction of the courts in relation to the operation of the Asylum and Immigration Tribunal. -

This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from the King’S Research Portal At

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ The case for abolishing jury trailas in the English legal system An analysis of the issues and consequences Yoshida, Narutoshi Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 The PhD Thesis The case for abolishing jury trials in the English legal system: an analysis of the issues and consequences PhD Candidate, The Dickson Poon School of Law, King’s College London Narutoshi Yoshida (0928748) 1 Abstract This thesis gives a critical study of the fairness and efficiency of the jury trial in the contemporary English justice system. -

Penalising Defendant Non-Cooperation in the Criminal Process and the Implications for English Criminal Procedure

Penalising Defendant Non-Cooperation in the Criminal Process and the Implications for English Criminal Procedure Abenaa Owusu-Bempah UCL PhD 1 I, Abenaa Owusu-Bempah confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. .......................................... Abenaa Owusu-Bempah 2 Abstract Requirements for the defendant to actively participate in the criminal process have been increasing in recent years such that the defendant can now be penalised for his non- cooperation. This thesis explores the procedural implications of penalising a defendant’s non- cooperation, particularly its effect on the English adversarial system. This thesis uses three key examples: 1) limitations placed on the privilege against self-incrimination, 2) adverse inferences drawn from a defendant’s silence, and 3) adverse inferences drawn from defence non- disclosure. The thesis explores how laws regarding the privilege against self-incrimination, the right to silence and pre-trial disclosure came to be reformed such that the defendant can now be penalised for his non-cooperation, and how these laws have been approached by the courts. A normative theory of criminal procedure is developed in the thesis and is used to challenge the idea of penalising defendant non-cooperation in the criminal process. The theory proposes that the criminal process should operate as a mechanism for calling the state to account for its accusations and request for official condemnation and punishment of the accused. Within this framework, the defendant should be free to choose whether or not to cooperate and participate throughout the process. -

Trial Issues in Protest Cases

Trial Issues in Protest Cases Keir Monteith QC, Garden Court Chambers (Chair) Russell Fraser, Garden Court Chambers Susan Wright, Garden Court Chambers Audrey Cherryl Mogan, Garden Court Chambers 7 July 2020 @gardencourtlaw Trial Issues: Removing Defences Audrey Cherryl Mogan, Garden Court Chambers 7 July 2020 @gardencourtlaw @gardencourtlaw DEFENCE OF NECESSITY R v Martin (Colin) (1989) 88 Cr App R 343 “First, English law does, in extreme circumstances, recognise a defence of necessity. Most commonly this defence arises as duress, that is pressure upon the accused’s will from the wrongful threats or violence of another. Equally, however, it can arise from other objective dangers threatening the accused or others. Arising thus it is conveniently called ‘duress of circumstances’. Secondly, the defence is available only if, from an objective standpoint, the accused can be said to be acting reasonably and proportionately in order to avoid a threat of death or serious injury. Thirdly, assuming the defence to be open to the accused on his account of the facts, the issue should be left to the jury, who should be directed to determine these two questions: first, was the accused, or may he have been, impelled to act as he did because as a result of what he reasonably believed to be the situation he had good cause to fear that otherwise death or serious physical injury would result? Second, if so, may a sober person of reasonable firmness, sharing the characteristics of the accused, have responded to the situation as the accused acted? If the answer to both these questions was yes then the … defence of necessity would have been established” (at pp. -

Report on Prosecution Appeals and Pre-Trial Hearings

REPORT PROSECUTION APPEALS AND PRE-TRIAL HEARINGS (LRC 81-2006) IRELAND Law Reform Commission 35-39 Shelbourne Road, Ballsbridge, Dublin 4 i © Copyright Law Reform Commission 2006 First Published November 2006 ISSN 1393-3132 ii THE LAW REFORM COMMISSION Background The Law Reform Commission is an independent statutory body whose main aim is to keep the law under review and to make practical proposals for its reform. It was established on 20 October 1975, pursuant to section 3 of the Law Reform Commission Act 1975. The Commission’s Second Programme for Law Reform, prepared in consultation with the Attorney General, was approved by the Government and copies were laid before both Houses of the Oireachtas in December 2000. The Commission also works on matters which are referred to it on occasion by the Attorney General under the terms of the Act. To date the Commission has published 79 Reports containing proposals for reform of the law; 11 Working Papers; 41 Consultation Papers; a number of specialised Papers for limited circulation; An Examination of the Law of Bail; and 26 Annual Reports in accordance with section 6 of the 1975 Act. A full list of its publications is contained on the Commission’s website at www.lawreform.ie Membership The Law Reform Commission consists of a President, one full-time Commissioner and three part-time Commissioners. The Commissioners at present are: President: The Hon Mrs Catherine McGuinness, former Judge of the Supreme Court Full-time Commissioner: Patricia T. Rickard-Clarke, Solicitor Part-time Commissioner: Professor Finbarr McAuley Part-time Commissioner: Marian Shanley, Solicitor Part-time Commissioner: Donal O’Donnell, Senior Counsel Secretary/Head of Administration: John Quirke iii Research Staff Director of Research: Raymond Byrne BCL, LLM, Barrister-at-Law Legal Researchers: John P. -

A Case of Self-Defense in Ireland Stacy Caplow Brooklyn Law School, [email protected]

Brooklyn Law School BrooklynWorks Faculty Scholarship Winter 2009 The aG elic Goetz: A Case of Self-Defense in Ireland Stacy Caplow Brooklyn Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/faculty Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation 17 Cardozo J. Int'l & Comp. L. 1 (2009) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of BrooklynWorks. ARTICLES THE GAELIC GOETZ: A CASE OF SELF- DEFENSE IN IRELAND Stacy Caplow* ABSTRACT For two years, the name Padraig Nally was a household word in Ireland. Nally killed an intruder on his farm in a rural community by shooting him in the back as he was running away, already injured from a brutal beating. The intruder was a Trav- eller, a minority group in Ireland that is mistrusted and ostra- cized. The killing was so far from the paradigmatic self-defense claim that the trial judge refused to instruct the jury on a full justification defense. Indicted for murder, Nally was convicted of manslaughter under a doctrine in Ireland called 'excessive force.' After the appeals court reversed because this instruction was tantamount to a directed verdict of conviction, Nally was retried and acquitted. The verdict was praised by Nally's sup- porters who sympathized with his fear and reaction, and criti- cized by those who claimed the crime was rooted in bigotry and prejudice. This case raises similar questions to the high profile U.S. -

Victims of Family Violence Who Commit Homicide

EMBARGOED UNTIL 11:00AM 11 NOVEMBER 2015 November 2015, Wellington, New Zealand | ISSUES PAPER 39 VICTIMS OF FAMILY VIOLENCE WHO COMMIT HOMICIDE EMBARGOED UNTIL 11:00AM 11 NOVEMBER 2015 Contents Foreword ............................................................................................................................................... vi Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................................. vii Call for submissions ........................................................................................................................... viii Chapter 1 Setting the scene ............................................................................................................... 11 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 11 Background ....................................................................................................................................... 12 Scope of this review .......................................................................................................................... 13 The Commission’s approach ............................................................................................................. 15 Structure of this Issues Paper ............................................................................................................ 18 Chapter 2 Understanding family violence -

Decisions Without Reasons ‒ Rethinking Jury Secrecy

Decisions Without Reasons – Rethinking Jury Secrecy ______________________________________________________________________________ Decisions Without Reasons – Rethinking Jury Secrecy Jason Donnelly BA (Macquarie University), LLB (University of Western Sydney) Decisions Without Reasons – Rethinking Jury Secrecy ______________________________________________________________________________ Decisions Without Reasons – Rethinking Jury Secrecy © 2008 Jason Donnelly All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Published by: BookPal Unit 4, 28 Boyland Avenue, Coopers Plains, QLD 4108 Tel: (07) 3712 2800 Web: www.bookpal.com.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Author: Donnelly, Jason Title: Decisions without reasons – rethinking jury secrecy / Jason Donnelly Edition: 1st ed. Subject: Jury. Trial practice. Dewey Number: 347.0752 ISBN 978-1-921300-96-7 Decisions Without Reasons – Rethinking Jury Secrecy ______________________________________________________________________________ For my Grandmother, Irmgard Napieracz Decisions Without Reasons – Rethinking Jury Secrecy ______________________________________________________________________________ Abstract It has often been asserted that the system of trial by jury in the Australian common law tradition represents a fundamental component of the criminal -

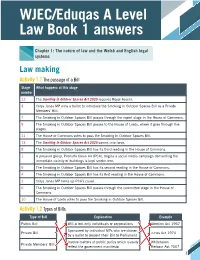

WJEC/Eduqas a Level Law Book 1 Answers

WJEC/Eduqas A Level Law Book 1 answers Chapter 1: The nature of law and the Welsh and English legal systems Law making Activity 1.1 The passage of a Bill Stage What happens at this stage number 12 The Smoking in Outdoor Spaces Act 2025 receives Royal Assent. 3 Cerys Jones MP wins a ballot to introduce the Smoking in Outdoor Spaces Bill as a Private Members’ Bill. 7 The Smoking in Outdoor Spaces Bill passes through the report stage in the House of Commons. 9 The Smoking in Outdoor Spaces Bill passes to the House of Lords, where it goes through five stages. 11 The House of Commons votes to pass the Smoking in Outdoor Spaces Bill. 13 The Smoking in Outdoor Spaces Act 2025 comes into force. 8 The Smoking in Outdoor Spaces Bill has its third reading in the House of Commons. 1 A pressure group, Promote Clean Air (PCA), begins a social media campaign demanding the immediate vicinity of buildings is kept smoke free. 5 The Smoking in Outdoor Spaces Bill has its second reading in the House of Commons. 4 The Smoking in Outdoor Spaces Bill has its first reading in the House of Commons. 2 Cerys Jones MP takes up PCA’s cause. 6 The Smoking in Outdoor Spaces Bill passes through the committee stage in the House of Commons. 10 The House of Lords votes to pass the Smoking in Outdoor Spaces Bill. Activity 1.2 Types of Bills Type of Bill Explanation Example Public Bill Will affect only individuals or corporations Abortion Act 1967 Sponsored by individual MPs who are chosen Private Bill Juries Act 1974 by a ballot to present their Bill to Parliament Involve matters of public policy which usually Whitehaven Private Members’ Bill reflect the government manifesto Harbour Act 2007 1 WJEC/Eduqas A Level Law Book 1 answers Activity 1.3 Theorist Fakebook Profiles could include the following content. -

Archbold Review 2

Issue 2 March 25, 2016 Issue 2 March 25, 2016 Archbold Review Cases in Brief Aggravated vehicle taking—strict liability of the Anti-Terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001, it TAYLOR [2016] UKSC 5; February 3, 2016 had been an offence under the Prevention of Corruption Aggravated taking without consent (Theft Act 1968 s.12A) Act 1906 s.1 to corrupt an agent of a foreign principal or required there to be fault in the quality of the driving that a foreign body. The 1906 Act was not confined to public caused injury. bodies, unlike the Public Bodies Corrupt Practices Act (1) R v Hughes [2013] 1 WLR 246 was not distinguishable. 1889. The two Acts created different species of offences, Hughes applied to the offence under the Road Traffic Act the one limited to public bodies (and not foreign public 1988 s.3ZB, and the Supreme Court in that case had left bodies), the other not so limited and utilising the concepts open the question of how far its reasoning applied to the of “agent” and “principal”, which were widely (and non- offence in s.12A. However, while there were relevant exhaustively) defined to embrace their normal language differences between the offences, the essential point made as well as legal meaning. Legislators at the time would in Hughes was common to both offences. The wording of have had no difficulty with these concepts embracing both both posited a direct causal connection between the driving foreign and domestic people. Had Parliament intended and the injury. If the requirement for causation was satisfied to exclude foreign principals from the scope of the Act, it by the mere fact that (in the s.12A case) the taking of the would have done so. -

Download Profile

Kirsty Brimelow QC Call: 1991 Silk: 2011 Email: [email protected] Profile “Kirsty is an excellent advocate. She is passionate in her dedication to various cases. She is extremely conscientious and extremely bright. She is someone who can pick something up and reshape it very quickly. She is extremely committed to human rights and has a breadth of international expertise. She is phenomenal in court as well.” (Criminal Solicitor, Chambers and Partners 2020) “She has been incredible. She has represented us in big judicial inquiries and she has attended a number of events for us….She is very grounded, down to earth and able to relate of people of all different cultures. She is also fearless…..She also has a fierce mind" (Chambers and Partner 2019) “She is fiercely intelligent” (Chambers and Partners 2020) Kirsty is the winner of the First 100 years Inspirational Barrister Woman in Law 2018 and Winner of The Advocate International Pro Bono Barrister of the year 2018. She is Head of the International Human Rights Team and former member of the Criminal Bar Association Executive. Kirsty was nominated as one of The Times “Top 100 Lawyers” and twice selected for the prestigious The Times “Lawyer of the Week”. She was twice listed as Management Today's most influential 35 women under 35 (2003 and 2005). Kirsty’s has in depth practitioner expertise in criminal law and also in public law and international human rights law. She has particular expertise in homicide, fraud, sexual offences, drugs and torture cases, child rights and vulnerable witness cases and the law of peaceful protest.