Musical Contests: Reflections on Musical Values in Popular Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Raja Mansingh Tomar Music and Arts University

RAJA MANSINGH TOMAR MUSIC AND ARTS UNIVERSITY Mahadaji Chok, Achaleshwar Mandir Marg, Gwalior – 474009, Madhya Pradesh Tel : 0751-2452650, 2450241, 4011838, Fax : 0751-4031934 Email : [email protected]; [email protected] Website : http://www.rmtmusicandartsuniversity.com Raja Mansingh Tomar Music and Arts University has been established at Gwalior under the Madhya Pradesh Act No. 3 of 2009 vide Raja Mansingh Tomar Sangit Evam Kala Vishwavidyalaya Adhiniyam, 2009. Unity in diversity is the cultural characteristic of India. The statements is fully in consonant with reference to Madhya Pradesh. It is one of the most recognized cetnres of arts and music from ancient times. It was also a centre for the teaching of Lord Krishna during the period of the Mahabharata in Sandipani Ashram of Ujjain. During the period of the Ramayan it was Chitrakoot which became the witness of Lord Rama’s penances. So many rivers create the aesthetic beauty of Madhya Pradesh, Apart from the various rivers such as Narmada, Kshipra, Betava, Sone, Indravati, Tapti and Chambal. Madhya Pradesh has also given birth to many saints, poets, musicians and great persons. Ashoka the great, was associated with Ujjaini and Vidisha, Mahendra and Sanghamitra started spreading the teachings of Buddhism from here. Madhya Pradesh is the pious land of Kalidas, Bhavabhuti, Tansen, Munj, Raja Bhoj, Vikramaditya, Baiju Bawra, Isuri, Patanjali Padmakar, and the great Hindi poet Keshav. This is the province which always encouraged and motivated the artists. Raja Man Singh Tomar also nutured the arts of music, dance and fine arts here. From time immemorial Madhya Pradesh has been resonated with the waves of Music. -

Rashid Khan Brochure-Opt.Pdf

SSrishtiSrishtirishti CenterCenter OfOf PerformingPerforming ArtsArts Website: http://www.srishti-dc.org Kamalika Sandell (703-774-6047) Paromita Ray (703-395-2765) Sunday Class Name Class Name Location 1-2 pm Classical Fusion Dance Bengali Language Class Sterling Community Center (Kids Ages 4-7, (Chandana Bose) Durba Ray) $95 - 8 weeks 120 Enterprise St $120 - 8 weeks Sterling, VA 20164 2-3 pm Classical Fusion Dance Bengali Music Class (Adults & Kids Ages 8+, (Kids Ages 4-7, Kamalika Durba Ray) Sandell) $120 - 8 weeks $120 - 8 weeks 3-4 pm Tabla Fine Arts Class (Chethan Ananth) (Shuddha Sanyal) $120 - 8 weeks $120 - 8 weeks 10-11 am Carnatic Vocal 12016 English Maple Ln, (Anu Iyer) Fairfax, VA 22030 $120 - 8 weeks *Sibling Discount for same class - 20% Gharana by Sumitro Majumdar The word gharana derives from ghar – hindi for house or family. The two gharanas, Agra and Gwalior are considered to be the oldest ones in khayal gayaki. It is contended that Rampur-Sahaswan gharana, an offspring of Gwalior gharana was started by Ustad Enayet Hussein Khan. His two sons-in- law and disciples, Ustad Mushtaq Hussein Khan (son of the famous Quwaal Kahlan Khan) and Ustad Nissar Hussein Khan extended the gayaki and made it even more popular and famous. The latter brought into his gayaki several components of Agra gharana while the former’s was tantalizingly close to Gwalior. Gharana does not constrict an artiste. Indian music is dynamic, and while a gharana teaches its students to sing a raga following certain tenets, improvisation, enrichment and embellishment are not discouraged. -

Dated : 23/4/2016

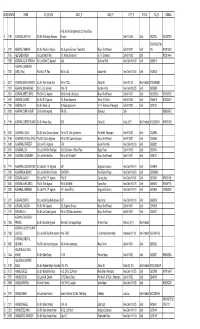

Dated : 23/4/2016 Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name Defaulting Year 01750017 DUA INDRAPAL MEHERDEEP U72200MH2008PTC184785 ALFA-I BPO SERVICES 2009-10 PRIVATE LIMITED 01750020 ARAVIND MYLSWAMY U01120TZ2008PTC014531 M J A AGRO FARMS PRIVATE 2008-09, 2009-10 LIMITED 01750025 GOYAL HEMA U18263DL1989PLC037514 LEISURE WEAR EXPORTS 2007-08 LTD. 01750030 MYLSWAMY VIGNESH U01120TZ2008PTC014532 M J V AGRO FARM PRIVATE 2008-09, 2009-10 LIMITED 01750033 HARAGADDE KUMAR U74910KA2007PTC043849 HAVEY PLACEMENT AND IT 2008-09, 2009-10 SHARATH VENKATESH SOLUTIONS (INDIA) PRIVATE 01750063 BHUPINDER DUA KAUR U72200MH2008PTC184785 ALFA-I BPO SERVICES 2009-10 PRIVATE LIMITED 01750107 GOYAL VEENA U18263DL1989PLC037514 LEISURE WEAR EXPORTS 2007-08 LTD. 01750125 ANEES SAAD U55101KA2004PTC034189 RAHMANIA HOTELS 2009-10 PRIVATE LIMITED 01750125 ANEES SAAD U15400KA2007PTC044380 FRESCO FOODS PRIVATE 2008-09, 2009-10 LIMITED 01750188 DUA INDRAPAL SINGH U72200MH2008PTC184785 ALFA-I BPO SERVICES 2009-10 PRIVATE LIMITED 01750202 KUMAR SHILENDRA U45400UP2007PTC034093 ASHOK THEKEDAR PRIVATE 2008-09, 2009-10 LIMITED 01750208 BANKTESHWAR SINGH U14101MP2004PTC016348 PASHUPATI MARBLES 2009-10 PRIVATE LIMITED 01750212 BIAPPU MADHU SREEVANI U74900TG2008PTC060703 SCALAR ENTERPRISES 2009-10 PRIVATE LIMITED 01750259 GANGAVARAM REDDY U45209TG2007PTC055883 S.K.R. INFRASTRUCTURE 2008-09, 2009-10 SUNEETHA AND PROJECTS PRIVATE 01750272 MUTHYALA RAMANA U51900TG2007PTC055758 NAGRAMAK IMPORTS AND 2008-09, 2009-10 EXPORTS PRIVATE LIMITED 01750286 DUA GAGAN NARAYAN U74120DL2007PTC169008 -

Pandit Ravi Shankar—Tansen of Our Times

Occ AS I ONAL PUBLicATION 47 Pandit Ravi Shankar—Tansen of our Times by S. Kalidas IND I A INTERNAT I ONAL CENTRE 40, MAX MUELLER MARG , NEW DELH I -110 003 TEL .: 24619431 FAX : 24627751 1 Occ AS I ONAL PUBLicATION 47 Pandit Ravi Shankar—Tansen of our Times The views expressed in this publication are solely those of the author and not of the India International Centre. The Occasional Publication series is published for the India International Centre by Cmde. (Retd.) R. Datta. Designed and produced by FACET Design. Tel.: 91-11-24616720, 24624336. Pandit Ravi Shankar—Tansen of our Times Pandit Ravi Shankar died a few months ago, just short of his 93rd birthday on 7 April. So it is opportune that we remember a man whom I have rather unabashedly called the Tansen of our times. Pandit Ravi Shankar was easily the greatest musician of our times and his death marks not only the transience of time itself, but it also reminds us of the glory that was his life and the immortality of his legacy. In the passing of Robindro Shaunkar Chowdhury, as he was called by his parents, on 11 December in San Diego, California, we cherish the memory of an extraordinary genius whose life and talent spanned almost the whole of the 20th century. It crossed all continents, it connected several genres of human endeavour, it uplifted countless hearts, minds and souls. Very few Indians epitomized Indian culture in the global imagination as this charismatic Bengali Brahmin, Pandit Ravi Shankar. Born in 1920, Ravi Shankar not only straddled two centuries but also impacted many worlds—the East, the West, the North and the South, the old and the new, the traditional and the modern. -

Final Electoral Roll

FINAL ELECTORAL ROLL - 2021 STATE - (S12) MADHYA PRADESH No., Name and Reservation Status of Assembly Constituency: 15-GWALIOR(GEN) Last Part No., Name and Reservation Status of Parliamentary Service Constituency in which the Assembly Constituency is located: 3-GWALIOR(GEN) Electors 1. DETAILS OF REVISION Year of Revision : 2021 Type of Revision : Special Summary Revision Qualifying Date :01/01/2021 Date of Final Publication: 15/01/2021 2. SUMMARY OF SERVICE ELECTORS A) NUMBER OF ELECTORS 1. Classified by Type of Service Name of Service No. of Electors Members Wives Total A) Defence Services 1199 36 1235 B) Armed Police Force 0 0 0 C) Foreign Service 0 0 0 Total in Part (A+B+C) 1199 36 1235 2. Classified by Type of Roll Roll Type Roll Identification No. of Electors Members Wives Total I Original Mother roll Integrated Basic roll of revision 1202 36 1238 2021 II Additions Supplement 1 After Draft publication, 2021 2 0 2 List Sub Total: 2 0 2 III Deletions Supplement 1 After Draft publication, 2021 5 0 5 List Sub Total: 5 0 5 Net Electors in the Roll after (I + II - III) 1199 36 1235 B) NUMBER OF CORRECTIONS/MODIFICATION Roll Type Roll Identification No. of Electors Supplement 1 After Draft publication, 2021 0 Total: 0 Elector Type: M = Member, W = Wife Page 1 Final Electoral Roll, 2021 of Assembly Constituency 15-GWALIOR (GEN), (S12) MADHYA PRADESH A . Defence Services Sl.No Name of Elector Elector Rank Husband's Address of Record House Address Type Sl.No. Officer/Commanding Officer for despatch of Ballot Paper (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) -

Indian Music and Mian Tansen

Indian Music and Mian Tansen Pandit Birendra Kishore Roy Chowdhury Indian Music and Mian Tansen' is a highly informative small book about Hindustani music, written by Pt. Birendra Kishore Roy Choadhury, self published in the late 1950's. He explains much about the traditional lineages in North Indian music. 2 About the Author 3 4 Chapter 1 - THE HINDUSTHANI CLASSICAL MUSIC Chapter 2 - THE FOUR BANIS OF THE DHRUBAPADA Chapter 3 - TANSEN SCHOOL OF MUSIC Chapter 4 - TANSEN'S DESCENDANTS IN VARANASI Chapter 5 - SENI GHARANA AT RAMPUR STATE Chapter 6 - TANSEN AND RABINDRANATH 5 Chapter One The Indian classical music had a divine origin according to the ancient seers of India. Both the vedic and the Gandharva systems of music were nurtured in the hermitage of Rishis. Of course the kings who were the disciples of those great teachers give proper scopes for the demonstrations of their musical teachings. After the end of Pouranic period a vast culture of music and arts grew up in India as integral parts of the temple worship. The same culture was propagated by the kings in the royal courts as those notable men were devoted to the deity of the temples. Thus the development of the classical music or Marga sangeet of India lay in the hands ofthe priest classes attached to the temples with the patronage of the kings. The demonstrations took place both in the temples well as in the royal palaces. These temples and palaces contained spacious hall for staging demonstrations of the music, dance and the theatres. The kings used to preserve the lines of top ranking artists attached to the temples and courts by providing fixed allowances and rent - free pieces of lands handed over to them for their hereditary possesion and enjoyment. -

Main Voter List 08.01.2018.Pdf

Sl.NO ADM.NO NAME SO_DO_WO ADD1_R ADD2_R CITY_R STATE TEL_R MOBILE 61-B, Abul Fazal Apartments 22, Vasundhara 1 1150 ACHARJEE,AMITAVA S/o Shri Sudhamay Acharjee Enclave Delhi-110 096 Delhi 22620723 9312282751 22752142,22794 2 0181 ADHYARU,YASHANK S/o Shri Pravin K. Adhyaru 295, Supreme Enclave, Tower No.3, Mayur Vihar Phase-I Delhi-110 091 Delhi 745 9810813583 3 0155 AELTEMESH REIN S/o Late Shri M. Rein 107, Natraj Apartments 67, I.P. Extension Delhi-110 092 Delhi 9810214464 4 1298 AGARWAL,ALOK KRISHNA S/o Late Shri K.C. Agarwal A-56, Gulmohar Park New Delhi-110 049 Delhi 26851313 AGARWAL,DARSHANA 5 1337 (MRS.) (Faizi) W/o Shri O.P. Faizi Flat No. 258, Kailash Hills New Delhi-110 065 Delhi 51621300 6 0317 AGARWAL,MAM CHANDRA S/o Shri Ram Sharan Das Flat No.1133, Sector-29, Noida-201 301 Uttar Pradesh 0120-2453952 7 1427 AGARWAL,MOHAN BABU S/o Dr. C.B. Agarwal H.No. 78, Sukhdev Vihar New Delhi-110 025 Delhi 26919586 8 1021 AGARWAL,NEETA (MRS.) W/o Shri K.C. Agarwal B-608, Anand Lok Society Mayur Vihar Phase-I Delhi-110 091 Delhi 9312059240 9810139122 9 0687 AGARWAL,RAJEEV S/o Shri R.C. Agarwal 244, Bharat Apartment Sector-13, Rohini Delhi-110 085 Delhi 27554674 9810028877 11 1400 AGARWAL,S.K. S/o Shri Kishan Lal 78, Kirpal Apartments 44, I.P. Extension, Patparganj Delhi-110 092 Delhi 22721132 12 0933 AGARWAL,SUNIL KUMAR S/o Murlidhar Agarwal WB-106, Shakarpur, Delhi 9868036752 13 1199 AGARWAL,SURESH KUMAR S/o Shri Narain Dass B-28, Sector-53 Noida, (UP) Uttar Pradesh0120-2583477 9818791243 15 0242 AGGARWAL,ARUN S/o Shri Uma Shankar Agarwal Flat No.26, Trilok Apartments Plot No.85, Patparganj Delhi-110 092 Delhi 22433988 16 0194 AGGARWAL,MRIDUL (MRS.) W/o Shri Rajesh Aggarwal Flat No.214, Supreme Enclave Mayur Vihar Phase-I, Delhi-110 091 Delhi 22795565 17 0484 AGGARWAL,PRADEEP S/o Late R.P. -

AJEET SINGH Mechanical Koncept Mahindra Automobiles & Apex T G India Pvt

SUMMER PLACEMENT w w w . m a n g a l m a y . o r g 20 Students' Profiles MANGALMAY GROUP OF INSTITUTIONS 17 Professional Transformation B.TECH AASHU Mechanical ABHISHEK GURG Mechanical Koncept Mahindra Automobiles & Apex T G India Pvt. Ltd. ABHISHEK NAGAR Mechanical Online Course on 'Begins Robotics' from University of Reading •Name •Branch •Training www.mangalmay.org SUMMER PLACEMENT w w w . m a n g a l m a y . o r g 20 Students' Profiles MANGALMAY GROUP OF INSTITUTIONS 17 Professional Transformation B.TECH AJEET SINGH Mechanical Koncept Mahindra Automobiles & Apex T G India Pvt. Ltd. AMAN KUMAR Mechanical Bihar State Power Generation Co. Ltd BHARAT BHUSHAN Mechanical Param Dairy Ltd •Name •Branch •Training www.mangalmay.org SUMMER PLACEMENT w w w . m a n g a l m a y . o r g 20 Students' Profiles MANGALMAY GROUP OF INSTITUTIONS 17 Professional Transformation B.TECH DEEPAK KUMAR Mechanical Koncept Mahindra Automobiles & Apex T G India Pvt. Ltd. DEEPAK KR. KUSHWAHA Mechanical Koncept Mahindra Automobiles & Apex T G India Pvt. Ltd. GAURAV KUMAR Mechanical Koncept Mahindra Automobiles & Apex T G India Pvt. Ltd. •Name •Branch •Training www.mangalmay.org SUMMER PLACEMENT w w w . m a n g a l m a y . o r g 20 Students' Profiles MANGALMAY GROUP OF INSTITUTIONS 17 Professional Transformation B.TECH KUNDAN KUMAR Mechanical Koncept Mahindra Automobiles & Apex T G India Pvt. Ltd. LAVKESH AGARWAL Mechanical Param Dairy Ltd MD FAISAL KHAN Mechanical In Plant training on Production shop, CNC milling , CNC Turning From INDO DANISH TOOL ROOM •Name •Branch •Training www.mangalmay.org SUMMER PLACEMENT w w w . -

Portrait of Tansen

Portrait of Tansen Moti Chandra There is a genuine desire among music lovers to discover the person ality of a great artist. Stray details of his life, lively anecdotes, stirring or evocative moments during a performance go to build a picture of the man. And the externals of his personality are indicated by portraits, which, for all their limitations, afford a glimpse of the maestro. The first six Moghul rulers prized learning and culture, and, above all, the art of miniature painting. While Humayun took the initial steps to develop this branch, it was Akbar who laid the actual foundations of a proper school of this art form. The city built by Akbar at Fatehpur Sikri was the ideal locale for a community of craftsmen and aesthetes devoted to the pursuit of the arts. That remarkable chronicler of the times, Abul Fazl, has in his two works, the Akbar Namah and the Aini Akbari, left us a faithful account of the varied interests of Akbar's court. Akbar attracted a wealth of talent towards himself. The Aini Akbari has a special chapter on the art of painting and mentions Akbar's personal interest in the atelier at his court. The master painters were the two Persians, Abdus Samad and Mir Sayyid Ali; the rest of the artists were mainly Hindus. The painters concentrated on two branches of the art of miniature: book illustration and portraiture. In drawing a portrait, the artist's primary concern was to seize a likeness. Thus we have a pictorial record of the Nine Jewels who added lustre to Akbar's court. -

Sarod & Scheherazade

NOTES ON THE PROGRAM BY LAURIE SHULMAN, ©2019 Sarod & Scheherazade ONE-MINUTE NOTES Amjad Ali Khan: Samaagam: A Concerto for Sarod, Concertante Group and String Orchestra Amjad Ali Kahn’s concerto fuses Northern Indian traditional instruments with a Western orchestra. Samaagam is Sanskrit for “flowing together,” an apt metaphor for Khan’s compelling concerto. He draws heavily on nearly a dozen ragas, the melodic building blocks of India’s classical music. Listen for drones and improvisatory passages that are cousins to jazz solos. Sarod, tabla and the NJSO’s principal string players all have their opportunity for exercising spontaneous musical creativity. Rimsky-Korsakov: Scheherazade Scheherazade features an obbligato role for our excellent concertmaster, Eric Wyrick. His recurring solo violin line represents the spellbinding voice of the Sultana as she relates the 1001 tales of the Arabian Nights, thereby staving off death by entertaining her husband. Scheherazade’s music is sinuous and seductive. The sultan’s theme, in the brasses, is barbaric, forceful and masculine. The writing is enchanting—a perfect blend of exoticism and impeccable orchestration. AMJAD ALI KHAN: Samagaam: A Concerto for Sarod, Concertante Group and String Orchestra AMJAD ALI KHAN Born: October 9, 1945, in Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh, India Composed: 2008 World Premiere: June 20, 2008, in Kirkwall, Orkney Islands, Scotland NJSO Premiere: These are the NJSO-premiere performances. Duration: 45 minutes Amjad Ali Khan is arguably the most celebrated Indian classical musician since Ravi Shankar. His instrument, the sarod, is a cousin of the sitar. Both are members of the lute family: plucked string instruments with a hollow body. -

1 Sample Question Paper on Cinema Prepared by : Naresh Sharma: Director

1 Sample question paper on cinema prepared by : Naresh Sharma: Director. CRAFT Film School.Delhi.www.craftfilmschool.com: [email protected] Disclaimer about this sample paper ( 50+28 Objective questions ) by Naresh Sharma: 1. This is to clarify that I, Naresh Sharma, neither was nor is a part of any advisory body to FTII or SRFTI , the authoritative agencies to set up such question paper for JET-2018 entrance exam or any similar entrance exam. 2. As being a graduate of FTII, Pune, 1993, and having 12 years of Industry experience in my quiver as well the 12 years of personal experience of film academics, as being the founder of CRAFT FILM SCHOOL, this sample question-answers format has been prepared to give the aspiring students an idea of variety of questions which can be asked in the entrance test. 3. The sample question paper is mainly focused on cinema, not in exhaustive list but just a suggestive list. 4. As JET - 2018 doesn't have any specific syllabus, so any question related to General Knowledge/Current Affair can be asked. 5. Since Cinema has been an amalgamation of varied art forms, Entrance Test intends to check as follows; a) Information; and b) Analysis level of students. 6. This sample is targeted towards objective question-answers, which can form part of 20 marks. One need to jot down similar questions connected with Literature/ Panting Music/ Dance / Photography/ Fine arts etc. For any Query, one can write: [email protected] 2 Sample question paper on cinema prepared by : Naresh Sharma: Director. -

Ragatime: Glimpses of Akbar's Court at Fatehpur Sikri

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14236/ewic/EVA2017.61 Ragatime: Glimpses of Akbar’s Court at Fatehpur Sikri Terry Trickett London NW8 9RE UK [email protected] ‘Ragatime’ is a piece of Visual Music in the form of a raga that recreates the sights and sounds of Akbar’s Court at Fatehpur Sikri. As the centre of the Mughal Empire for a brief period in the 16th century, Fatehpur Sikri was remarkable for its architecture, art and music. Akbar’s favourite musician, Mian Tansen, was responsible for developing a genre of Hindustani classical music known as dhrupad; it’s the principles of this genre that I’ve encapsulated in my own interpretation of Raga Bilaskhani Todi. Ragatime starts with a free flowing alap which, as tradition dictates, sets the rasa (emotion or sentiment) of the piece. The following section, gat, is announced by rhythmic drumming which signals the soloist to begin an extended improvisation on the Raga’s defined note pattern. It is the subtle differences in the order of notes, an omission of a dissonant note, an emphasis on a particular note, the slide from one note to another, and the use of microtones together with other subtleties, that demarcate one raga from another. To Western ears, raga is a musical form that remains ambiguous and elusive; only a declared master of the art, or guru, can breathe life into each raga as he or she unfolds and expands it. Similarly, a raga’s tala, or rhythm, requires a freedom of expression that embraces the ‘rhythm of the universe as personified by Shiva, Lord of the Dance’.